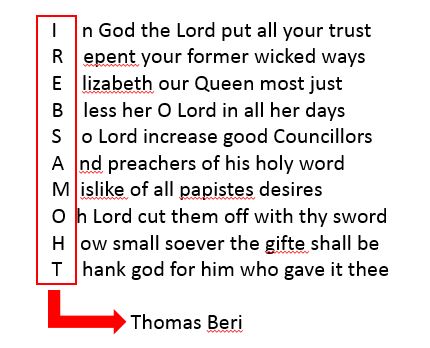

I mentioned in my blog last week that I’d been visiting the garden dedicated to a famous Londoner and it was a real thrill to discover some garden pavers with fascinating carvings (EC3N 4AT). The famous Londoner was, of course, Samuel Pepys and I haves since discovered a lot more about the carvings.

But first of all, some examples. The first one I noticed made me smile.

Pepys had been plagued by recurring stones since childhood and, at the age of 25, decided to tackle it once and for all and opt for surgery. He consulted a surgeon, Thomas Hollier, who worked for St Thomas’ Hospital and was one of the leading lithotomists (stone removers) of the time. The procedure was very risky, gruesome and, since anaesthetics were unknown in those days, excruciatingly painful. But Pepys survived and had the stone, ‘the size of a tennis ball’, mounted and kept it on his desk as a paperweight. It may even have been buried with him. One of the garden carvings shows a stone held in a pair of forceps …

You can read more about the procedure Pepys underwent here.

Pepys survived the Great Plague of 1665 even though he remained in London most of the time. The pestilence is referenced by a plague doctor carrying a winged hourglass and fully dressed in 17th century protective clothing …

No one at the time realised that the plague could be spread by fleas carried on rats. One of the species sits cheekily at the doctor’s feet.

There is a flea in the garden but it has nothing to do with the plague …

While visiting his bookseller on a frosty day in early January 1665 Pepys noticed a copy of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia, ‘which‘, Pepys recorded in his diary, ‘is so pretty that I presently bespoke it‘ …

Like many other readers after him, Pepys was immediately drawn in by the beautiful engravings printed in what was the world’s first fully-illustrated book of microscopy. When he picked up his own copy later in the month Pepys was even more pleased with the book, calling it ‘a most excellent piece . . . of which I am very proud‘. The following night he sat up until two o’clock in the morning reading it, and voted it ‘the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life‘. Here is the engraving Hooke made of a flea …

You can explore the wonders of Micrographia yourself by clicking on this link to the British Library website.

In the garden Pepys is commemorated with a splendid bust by Karin Jonzen (1914-1998), commissioned and erected by The Samuel Pepys Club in 1983 …

The plinth design was part of the recent project and the music carved on it is the tune of Beauty Retire, a song that Pepys wrote. So if you read music you can hear Pepys as well as see his bust …

Pepys was evidently extremely proud of Beauty Retire, for he holds a copy of the song in his most famous portrait by John Hayls, now in the National Portrait Gallery. A copy of the portrait hangs in the Pepys Library …

Every year, on the anniversary of his surgery, Pepys held what he called his ‘Stone Feast’ to celebrate his continued good health and there is a carving in the garden of a table laden with food and drink …

The Great Fire of London began on 2 September 1666 and lasted just under five days. One-third of London was destroyed and about 100,000 people were made homeless. He wrote in his diary …

I (went) down to the water-side, and there got a boat … through (the) bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods: poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till … some of them burned their wings and fell down.

A boat in the foreground with the City ablaze in the distance while a piece of furniture floats nearby …

His house was in the path of the fire and on September 3rd his diary tells us that he borrowed a cart ‘to carry away all my money, and plate, and best things‘. The following day he personally carried more items to be taken away on a Thames barge, and later that evening with Sir William Pen, ‘I did dig another [hole], and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.’ And here is his cheese and wine …

Why did he bury cheese? Read more about the value of Parmesan (then and now) here.

Then there are these musical instruments, all of which Pepys could play …

From the Pepys Club website: ‘To Pepys, music wasn’t just a pleasant pastime; it was also an art of great significance – something that could change lives and affect everyone who heard it. He was a keen amateur, playing various instruments and studying singing – he even designed a room in his home specially for music-making. He attended the services at the Chapel Royal; he collected a vast library of scores, frequented the theatre and concerts and even commented with affection on the ringing of the church bells that filled the air in London’s bustling streets where he lived and worked’.

The Navy Office where he worked, eventually rising to become Chief Secretary to the Admiralty …

There are thirty pavers in all and I shall return to them in a later blog. In the meantime, great credit is due to the folk who worked on this incredibly interesting project.

The designs were created by a team of students and alumni of City & Guilds London Art School working under the direction of Alan Lamb of Swan Farm Studios Ltd. Further contributions to the design were made by Sam Flintham, Jackie Blackman, Clem Nuthall, Tom Ball, Sae Na Ku, Sophie Woodhouse and Alan Lamb himself. Here are some pictures of the sculptors at work.

Tom Ball working on the flea …

Mike Watson working on Pepys’s monogram …

And finally, Alan Lamb working on a theorbo lute, another instrument Pepys could play …

Do visit the garden if you have the chance. Another of its interesting features is that it is irrigated by rainwater harvested from the roof of the hotel next door!

I have written about Pepys before : Samuel Pepys and his ‘own church’ and Samuel Pepys and the Plague.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …