One of the best pieces of advice I was given when I began to write about the City was to continually look up and it’s true to say that I have often been surprised by what I have observed – from the Cornhill Devils to Mercer Maidens to a beautiful lighthouse on, of all places, Moorgate.

It’s also true to say, however, that looking down can be just as interesting.

Like me, you must have occasionally wondered what symbols like these painted on roads and pavements actually signify. I found this nice collection at the east end of Carter Lane …

Well, wonder no more, all the answers are here. For example …

Not surprisingly, and used in warning signs the world over, red paint denotes electricity. Thus red lines show where electricity cables run and mean that anyone digging there must do so with extreme caution.

White is like a little Post-It note for future contractors …

Blue is usually for water pipes …

Yellow refers to all things gas …

A growing hue in the pavement-marking business is green, the colour of cable communications, which includes town and city CCTV networks and cable television lines …

And finally some others in orange …

All are explained in this fascinating article entitled ‘What do those squiggles on the pavement actually mean?‘ from which I have drawn extensively for this week’s blog.

Incidentally, whilst on Carter Lane I briefly looked up and was puzzled by the small plaque on the left of the parish boundary mark …

According to a document on the Essex Fire Brigade web site, FP stands for Fire Plug. Apparently in the early days of the fire service, and when many underground water pipes were made out of wood, firemen would dig down to the water main and bore a small, circular hole in the pipe to obtain a supply of water to fight the fire.

When finished, they would put a wooden plug into the hole, and leave an FP plate on a nearby wall to alert future firefighters that a water main with a plug already existed.

When wooden pipes were replaced by cast iron pipes in the 19th century, workmen would often bore a small hole in the pipe and fit with a wooden plug when they saw an FP plate. This would later be replaced with the Fire Hydrant method, which would be identified by a large H. Many thanks to the London Inheritance blog for this information.

Looking down can be a bit addictive and another puzzle it presented me with were these ‘V’- shaped incisions into kerb stones. I found a number of examples in EC1.

On Old Street …

And Dufferin Street …

And Roscoe Street …

Discovering what they might mean proved rather difficult and I entered a whole new world when I started my research. Look at this article entitled The World of Carvings and Stories and click on some of the useful links. I shall continue to look down and see if I encounter any more.

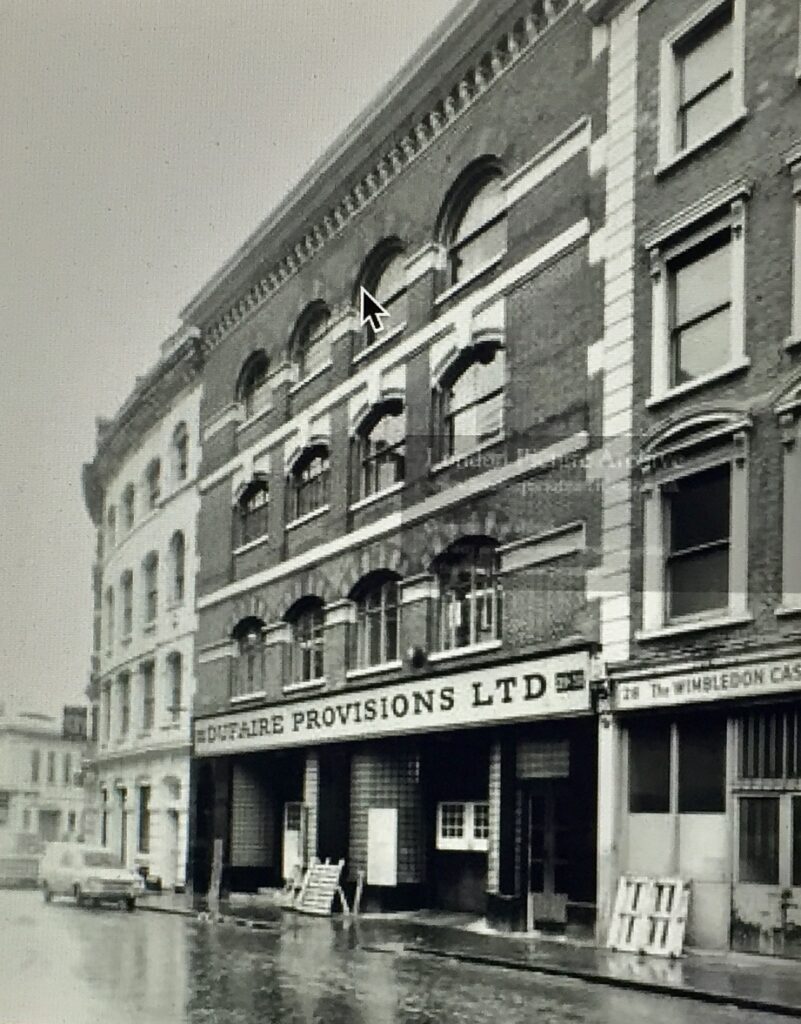

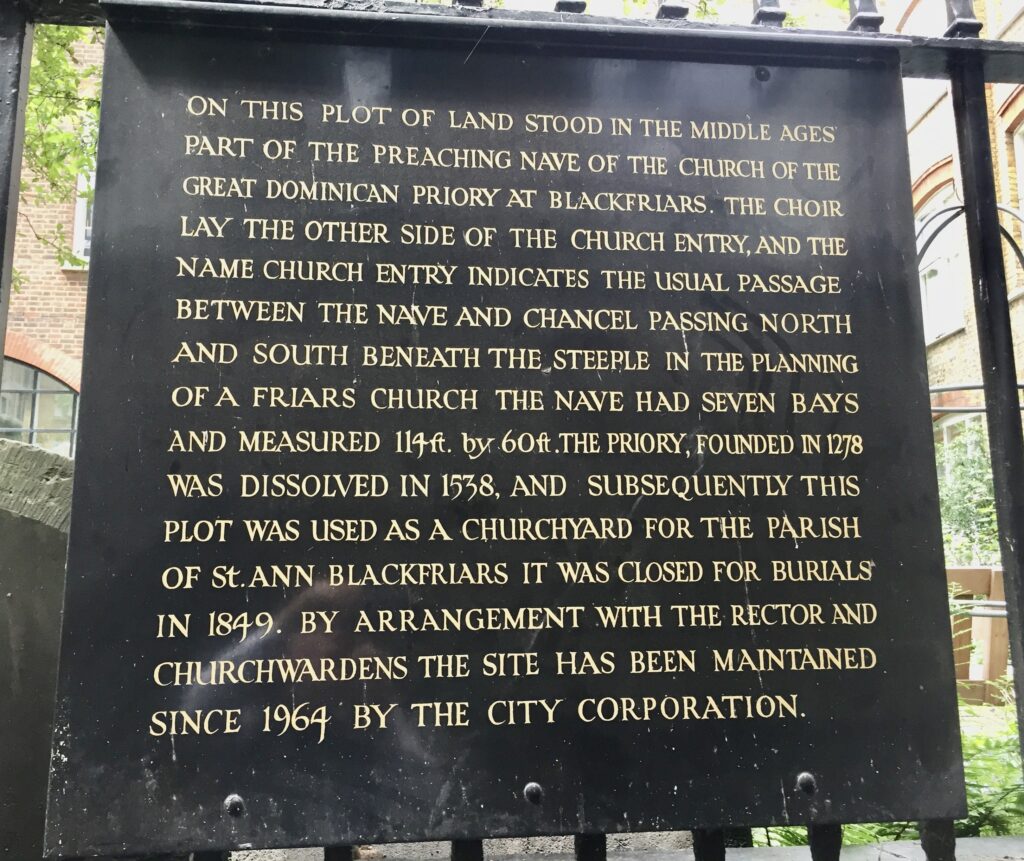

In last week’s blog I spoke of a mystery connected to these two gravestones in the old parish churchyard of St Ann Blackfriars in Church Entry (EC4V 5HB) …

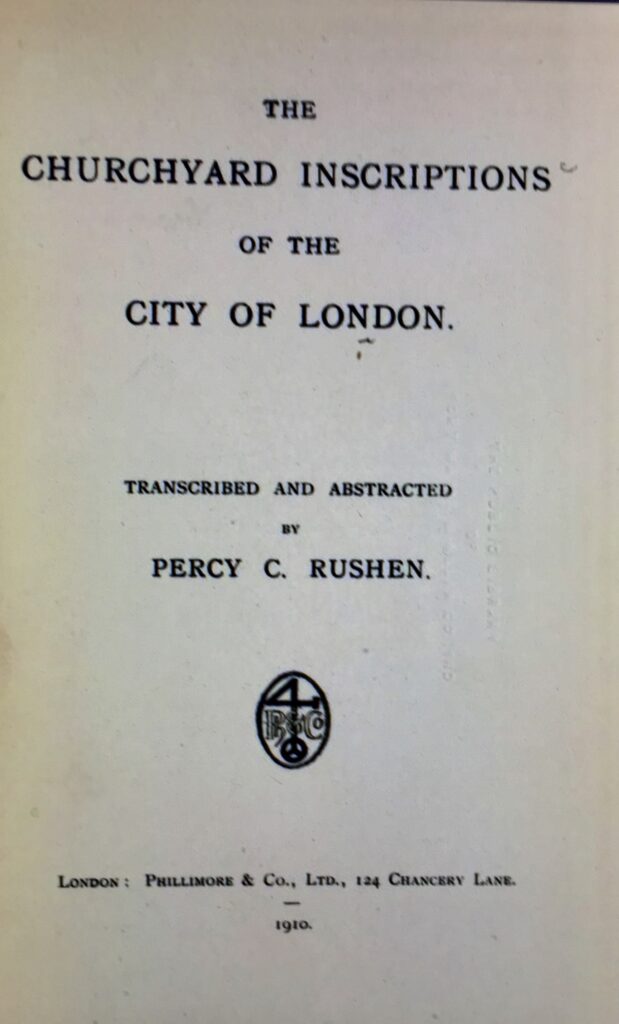

My ‘go to’ source of information when it comes to grave markers is the estimable Percy C. Rushen who published this guide in 1910 when he noticed that memorials were disappearing at a worrying rate due to pollution and redevelopment …

So when I came across the last two stones in this graveyard with difficult to read inscriptions I did what I normally do which is to consult Percy’s book in order to see what the full dedication was.

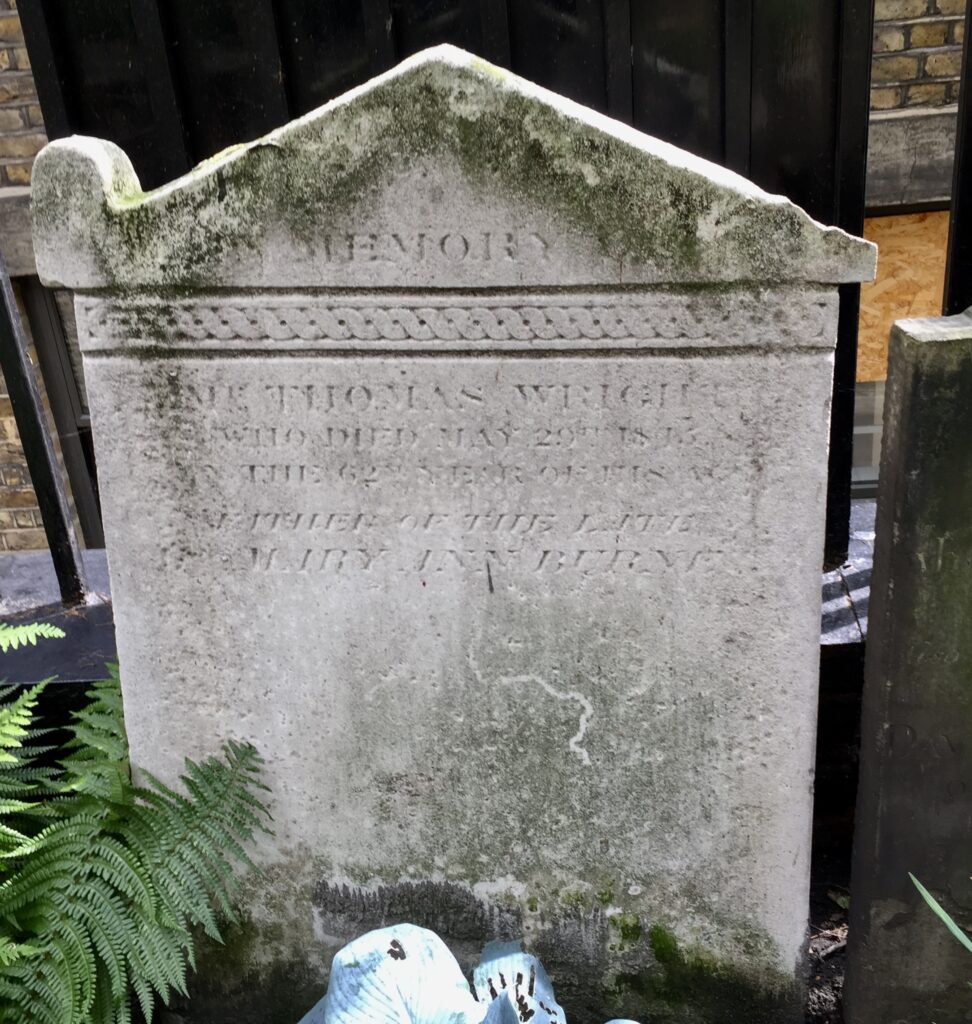

There was, however, a snag. Neither headstone is recorded in Percy’s list for St Ann Blackfriars. Let’s look at them one by one. This is the stone for Thomas Wright …

Fortunately, the book lists people in alphabetical order and, although there isn’t a Wright recorded at St Ann’s, there is one recorded at St Peter, Paul’s Wharf. It’s definitely the same one and reads as follows :

THOMAS WRIGHT, died 29 May 1845, father of the late Mrs Mary Ann Burnet.

The inscription of another stone recorded in the same churchyard reads …

CAROLINE, wife of JAMES BURNET , died 26 July 1830, aged 36.

MARY ANN, his second wife, died 12 April1840, aged 36.

JAMES BURNET, above, died … 1842, aged …3

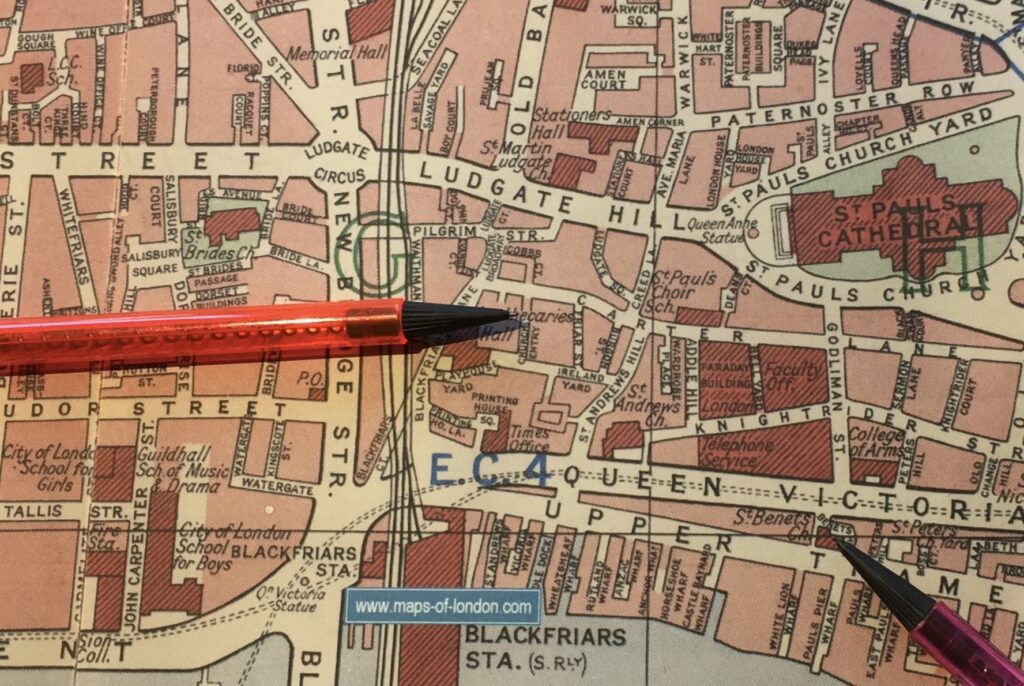

St Peter, Paul’s Wharf, was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and not rebuilt but obviously its churchyard was still there in 1910. And it was still there in the 1950s as this map shows. I have indicated it in the bottom right hand corner with the other pencil showing the location of Church Entry and St Ann’s burial ground …

This is the present day site of Thomas Wright’s original burial place, now Peter’s Hill and the approach to the Millennium Bridge …

The stone must have been moved some time in the mid-20th century, but the question is, was Thomas moved as well? Have his bones finally come to rest in Church Entry? I have been unable to find out.

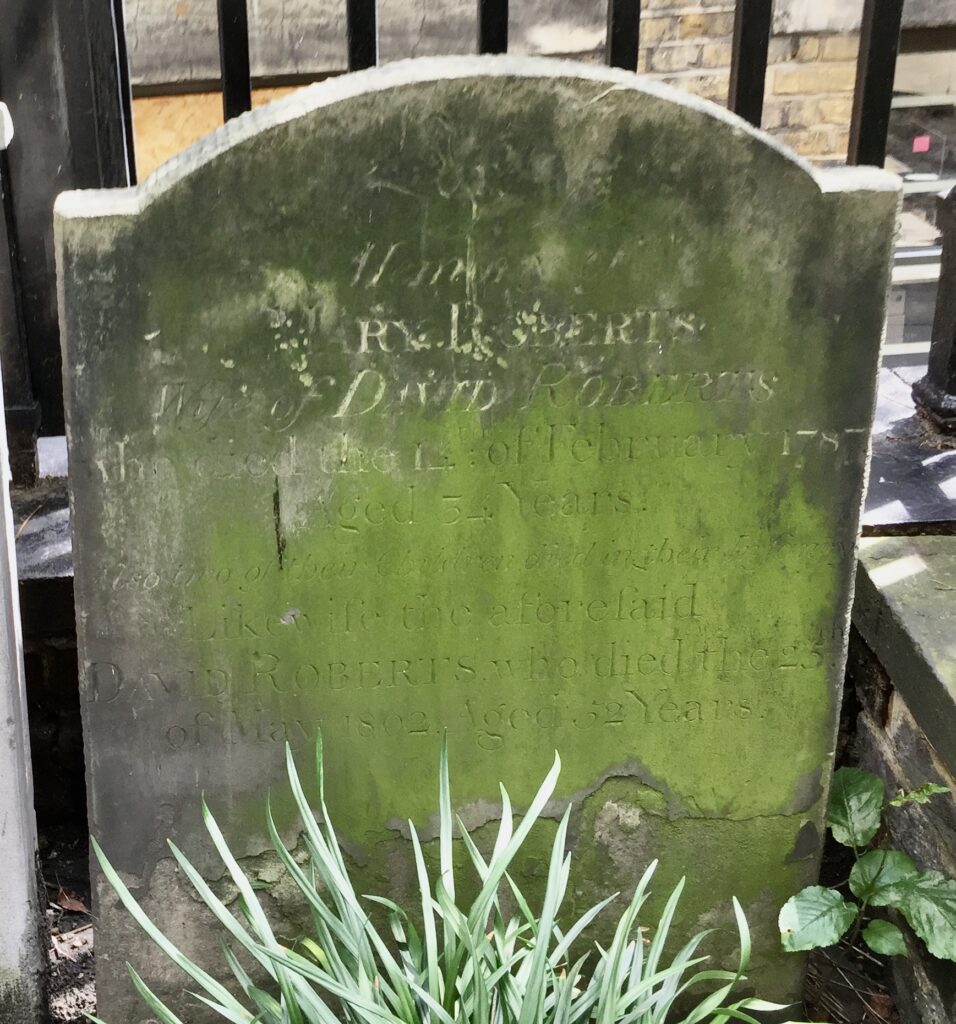

This is the headstone alongside Thomas’s …

It reads as follows …

In Memory of MARY ROBERTS who died the 14th February 1787. Also two of their children who died in their infancy like the wife of the aforesaid DAVID ROBERTS who died the 25th May 1802, aged 52 years.

I have read this to mean that Mary died in childbirth – a terrible risk at the time. About one in three children born in 1800 did not make it to their fifth birthday and maternal deaths at birth have been estimated at about five per thousand (although that is probably on the low side). Just by way of comparison, in 2016 to 2018, among the 2.2 million women who gave birth in the UK, 547 died during or up to a year after pregnancy from causes associated with their pregnancy. The 1800 equivalent rate would have meant 11,000 deaths.

If you are interested to know more about maternal mortality, its history and causes, you’ll find this incredibly informative article in The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Most disturbing is how doctors who discovered the underlying cause of many deaths were disbelieved and vilified by the medical profession as a whole, thus allowing unnecessarily high mortality to continue for decades.

The mystery surrounding this stone is that, although there are quite a few people called Roberts recorded in Percy’s memorial list, none of them are called Mary or David. So, assuming, the book is complete (and Percy was obviously very fastidious) I wonder where this marker comes from.

That’s all for this week – I shall continue to try to solve the mysteries I have written about.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …

https://www.instagram.com/london_city_gent/