Once surrounded by the throbbing printing presses of Fleet Street newspapers, Gough Square is today a quiet haven off the noisy main road. Now known as Dr Johnson’s House, 17 Gough Square was built by one Richard Gough, a City wool merchant, at the end of the seventeenth century. It is the only survivor from a larger development and Dr Johnson lived here from 1748 to 1759 whilst compiling his famous dictionary. It has been open to the public for many years but for some reason I’ve only just got around to visiting it …

The house has the first example of a Royal Society of Arts terracotta plaque (installed in 1898) commemorating Samuel Johnson’s residence here …

The way in …

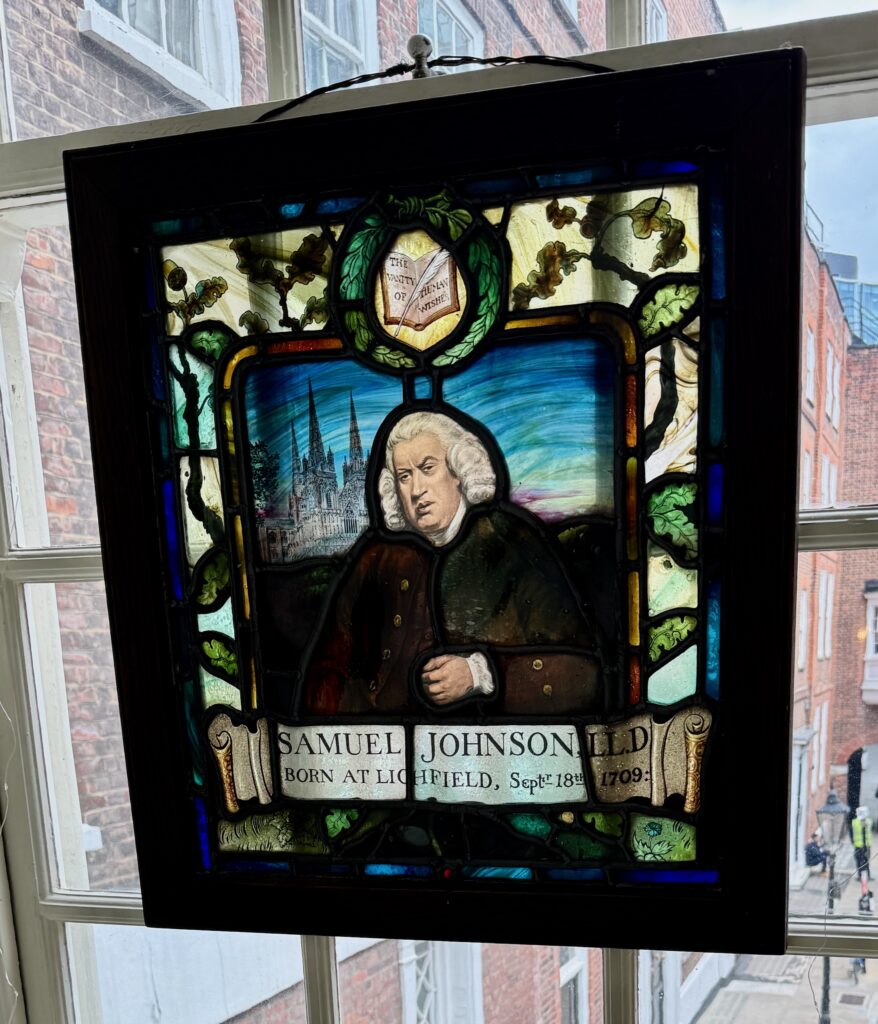

Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) was an English writer, lexicographer, critic, and moralist, widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in 18th-century English literature. Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, on September 18, 1709, he was the son of a bookseller. Despite battling poor health and financial hardship, he developed a voracious appetite for reading and classical learning.

Johnson attended Pembroke College, Oxford, in 1728, but was forced to leave after a year due to lack of funds. Although he did not complete a degree, his academic brilliance left a lasting impression. He moved to London in 1737 with his friend and former pupil David Garrick, who would later become a renowned actor. There, Johnson began his literary career with essays, translations, and poetry, steadily gaining recognition.

His most monumental achievement came in 1755 with the publication of A Dictionary of the English Language. A massive undertaking completed almost single-handedly, the dictionary was the most comprehensive English lexicon of its time and remained a standard reference for over a century. It established Johnson’s reputation as a leading intellectual so I head first to the top floor garrett where the great man worked. I can’t help but think of him grabbing the banister as he climbed the rickety, narrow staircase to the top floor …

The room where he worked. He was originally contracted to complete the project in just three years but in the end it took him just over eight to complete, with six helpers …

On the table is a facsimile of the final version which visitors can leaf through …

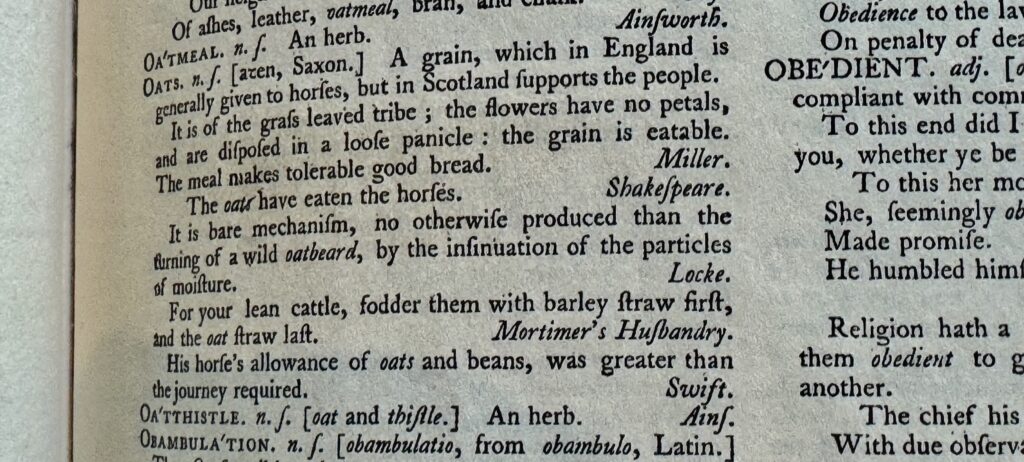

I made a point of looking up his famous (or infamous) definition of the word ‘Oats’ : ‘… grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people’.

Note that he not only defines the word but also alludes to other examples of it in context quoting Shakespeare, Locke, Mortimer’s Husbandry and Swift …

Other fascinating definitions include his own occupation as lexicographer: ‘a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words’.

I also like Mouth-friend: ‘One who professes friendship without intending it.’

And what about this elegant, succinct definition of History: ‘A narration of events and facts delivered with dignity’.

Other interesting sights I encountered as I wandered from floor to floor.

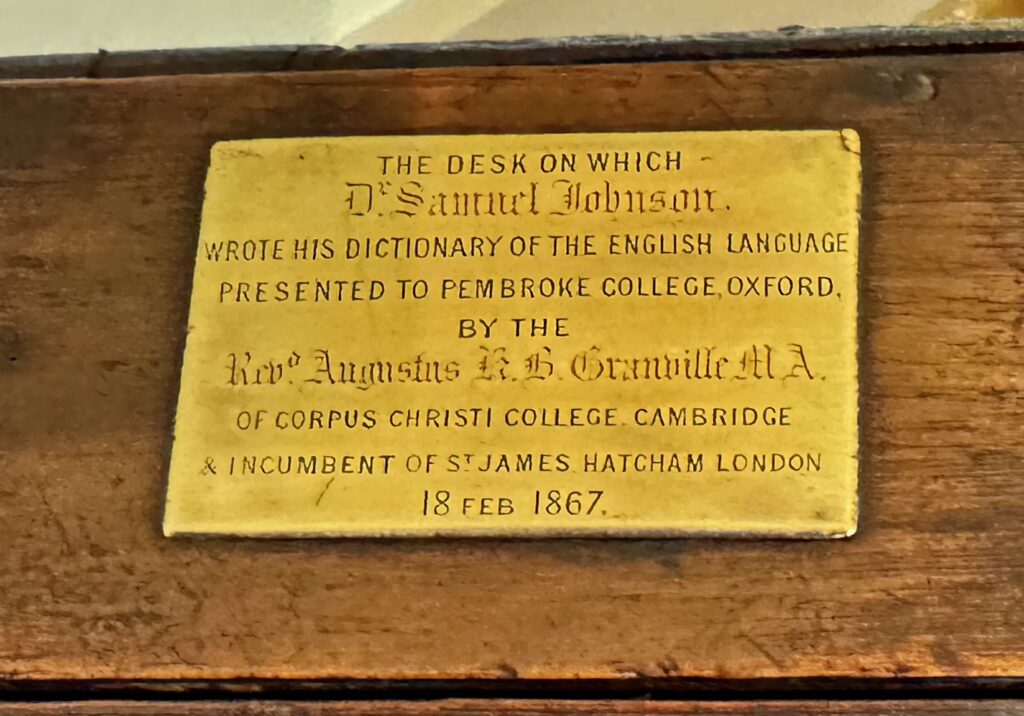

Dr Johnson’s dictionary desk on loan from Pembroke College …

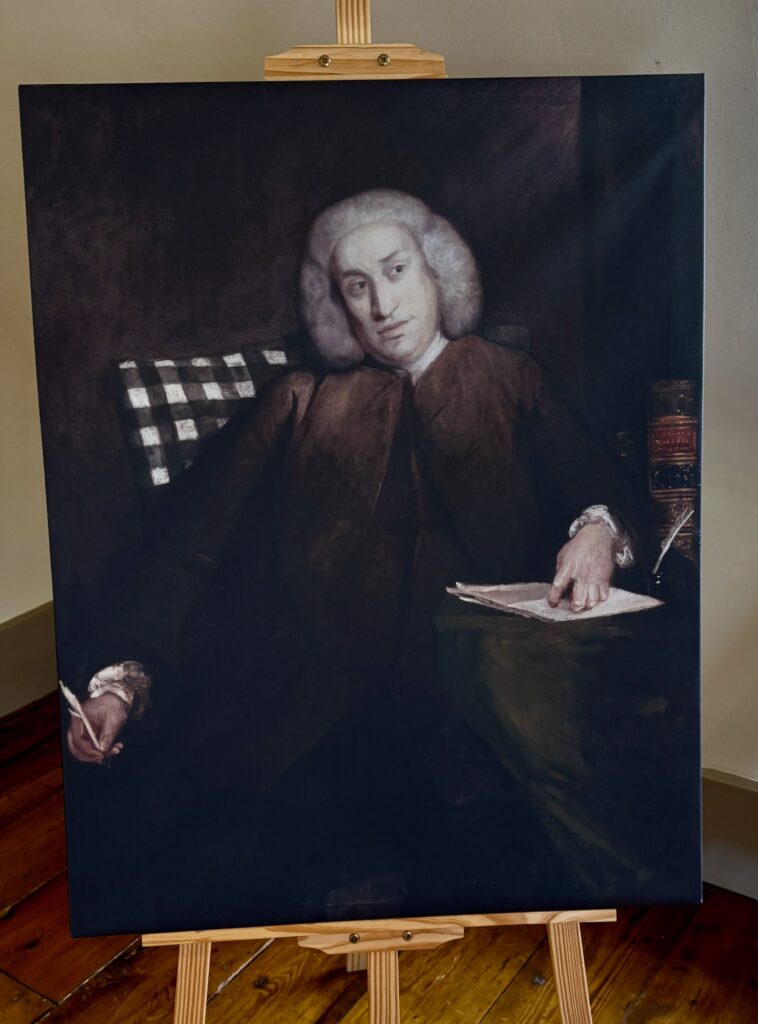

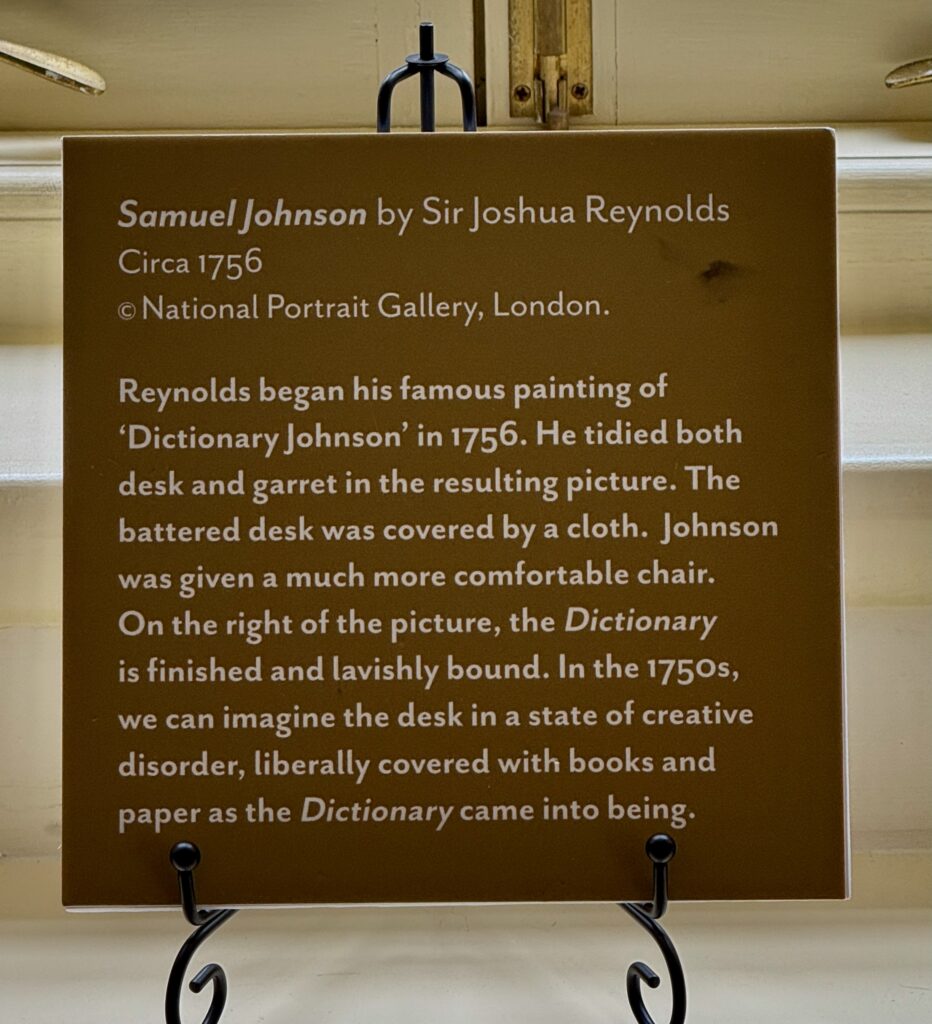

A famous portrait …

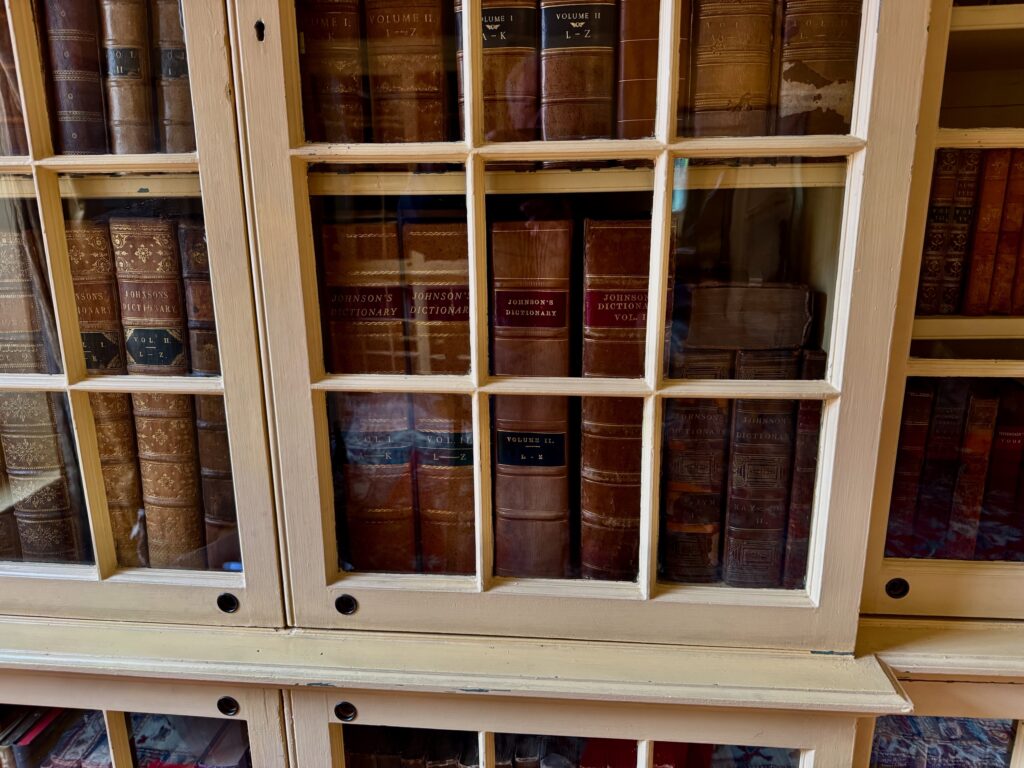

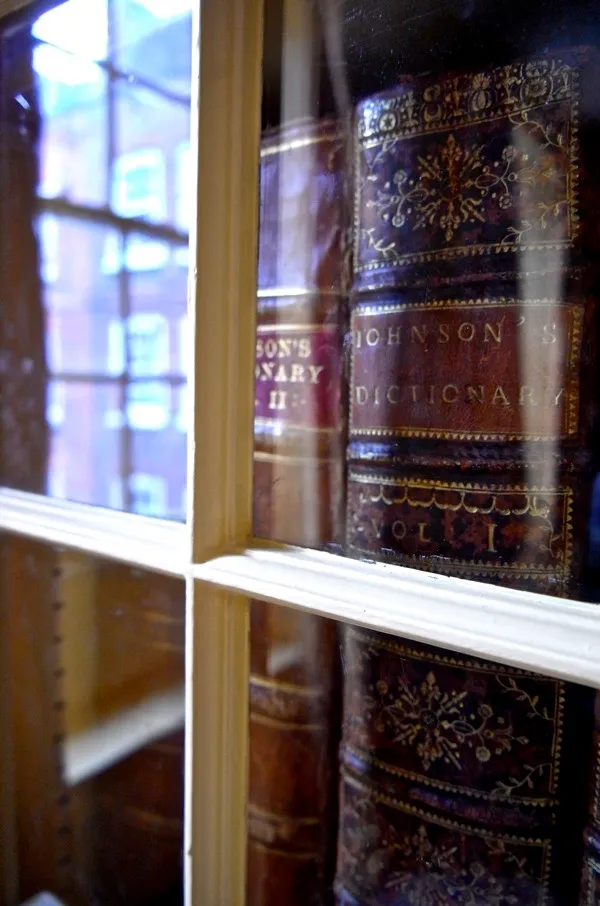

Bookcase with various editions of the work …

Johnson’s desk and chair …

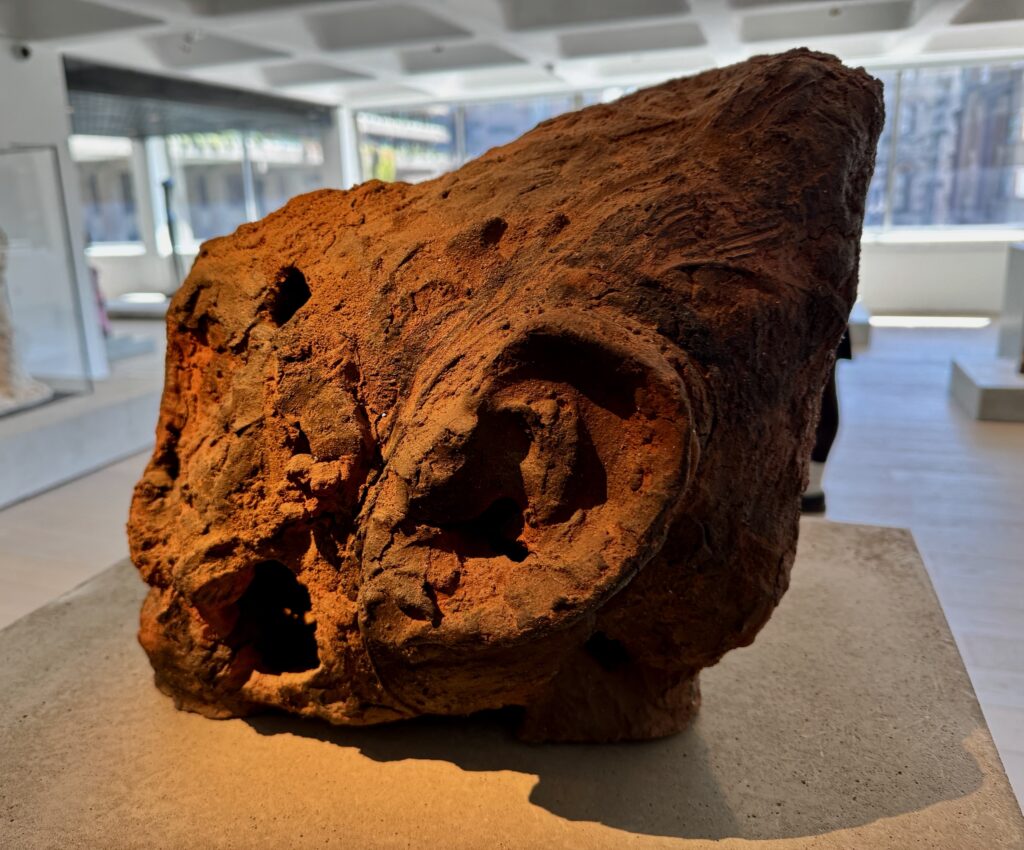

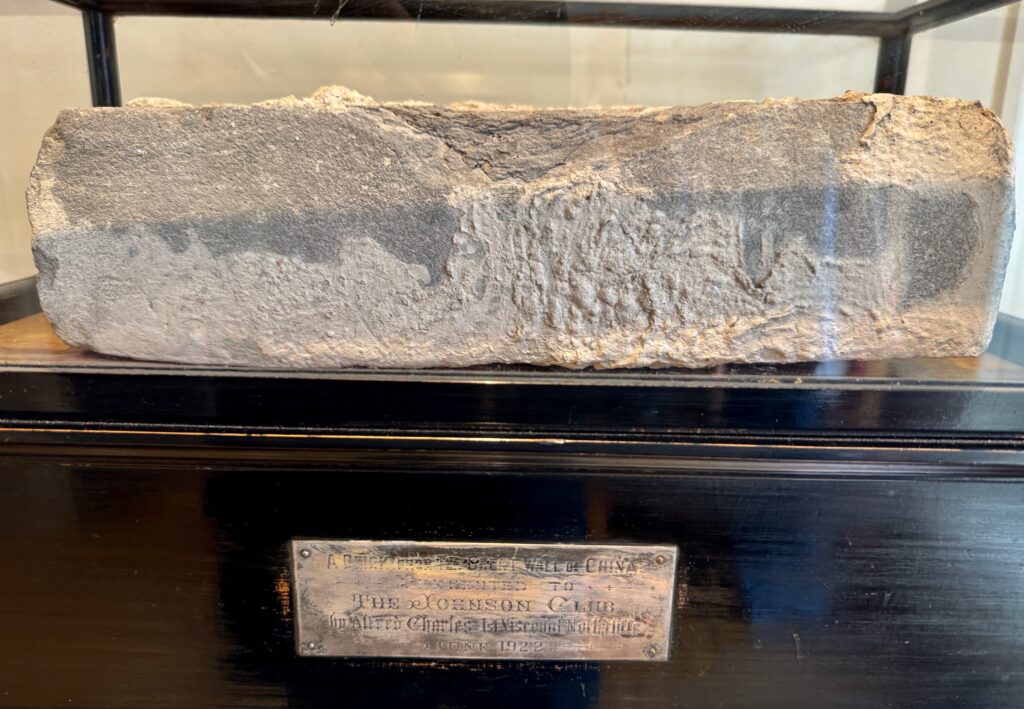

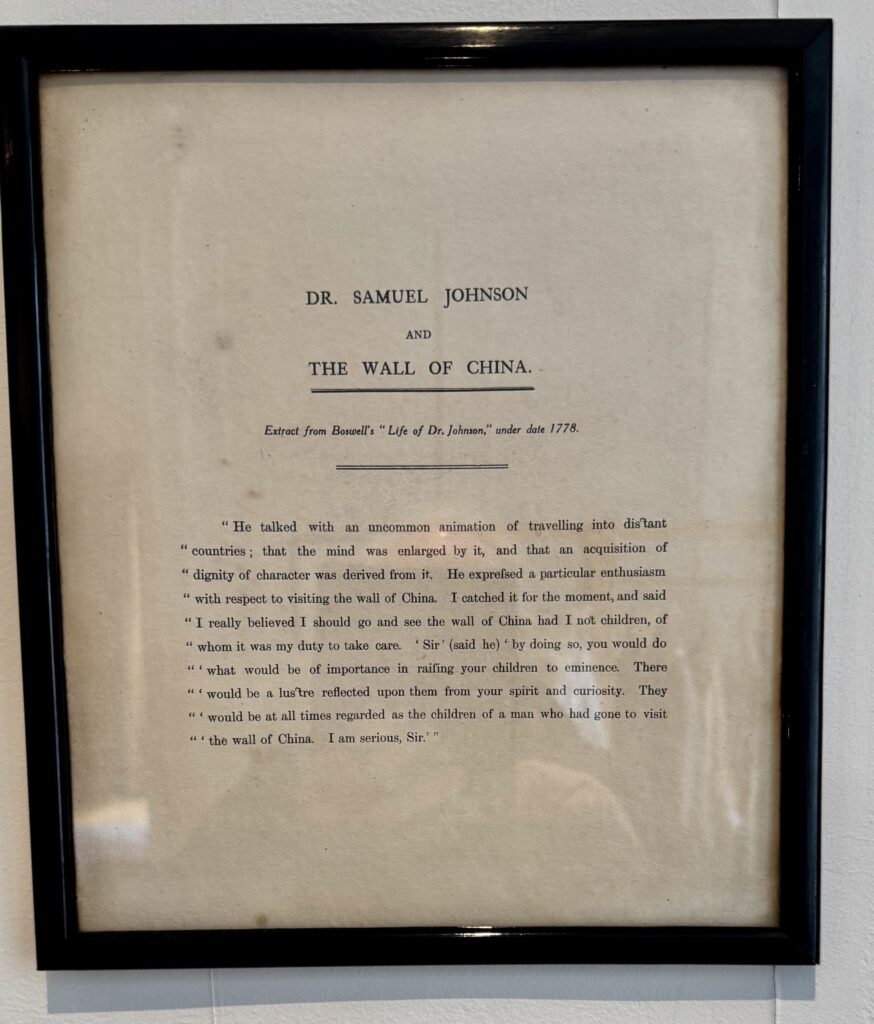

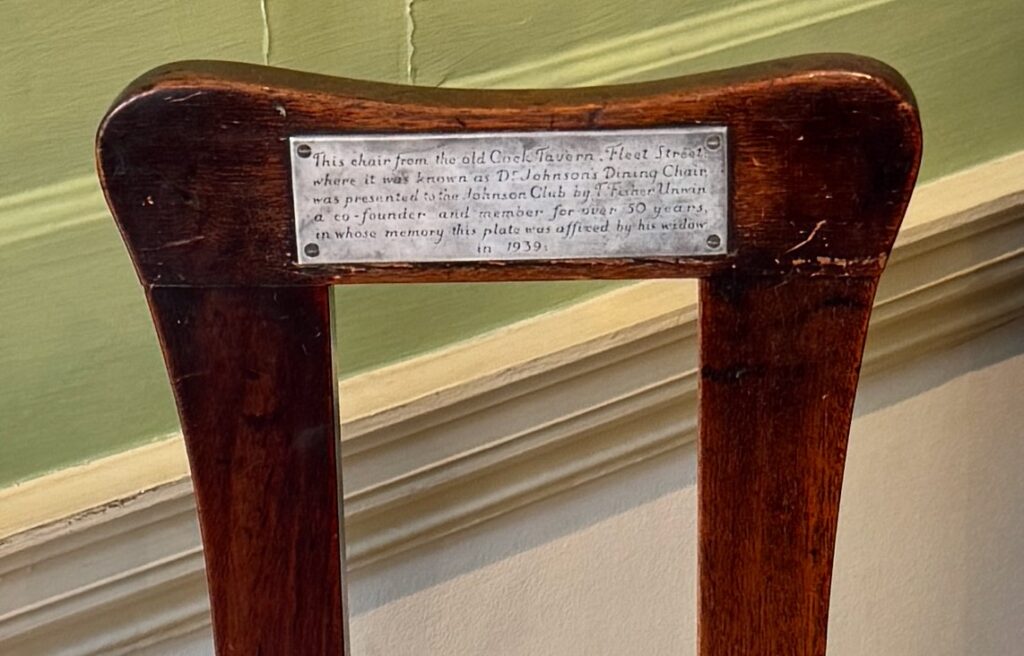

An odd piece of memorabilia from the Johnson Club (1922). A brick from the Great Wall of China …

The reason for its acquisition …

Note the portrait above the fireplace …

‘This portrait of Anna Williams was painted by Frances Reynolds, sister of the more renowned portraitist, Sir Joshua Reynolds. All were friends with Samuel Johnson. The sitter, Anna Williams, was a friend and housekeeper to Johnson from the early 1750s until her death in 1783. Johnson supported the impoverished Williams, the daughter of a failed inventor, for many decades and helped publish a miscellany of literary works for her benefit. Frances Reynolds has created a sensitive portrayal of Williams who, at an early age, was blinded by untreatable cataracts in both her eyes’ …

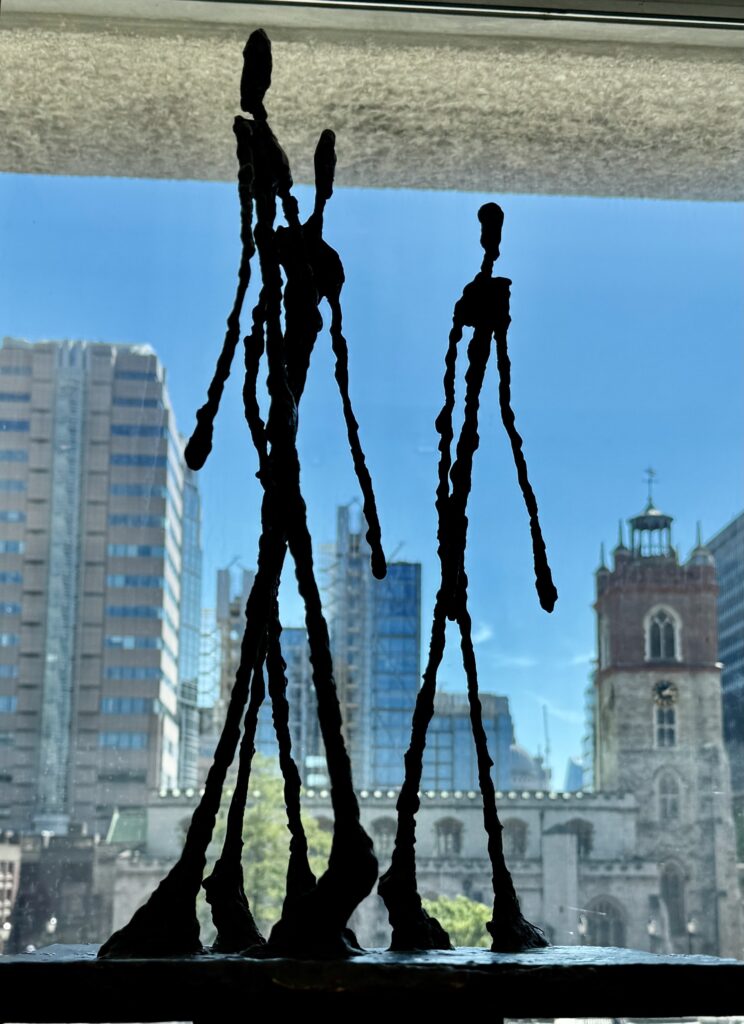

Dr Johnson and Mrs Siddons …

‘The celebrated actress Sarah Siddons specialised in tragic roles, which helped her maintain a dignity and good reputation. She met … Johnson near the end of his life and the episode was the inspiration for this painting by Frith. When there was no chair in Johnson’s house for the actress he remarked with charm: ‘Madam, you who so often occasion a want of seats to other people, will the more easily excuse the want of one yourself.’

David Garrick’s chest used for storing his costumes …

Dr Johnson’s straddling chair …

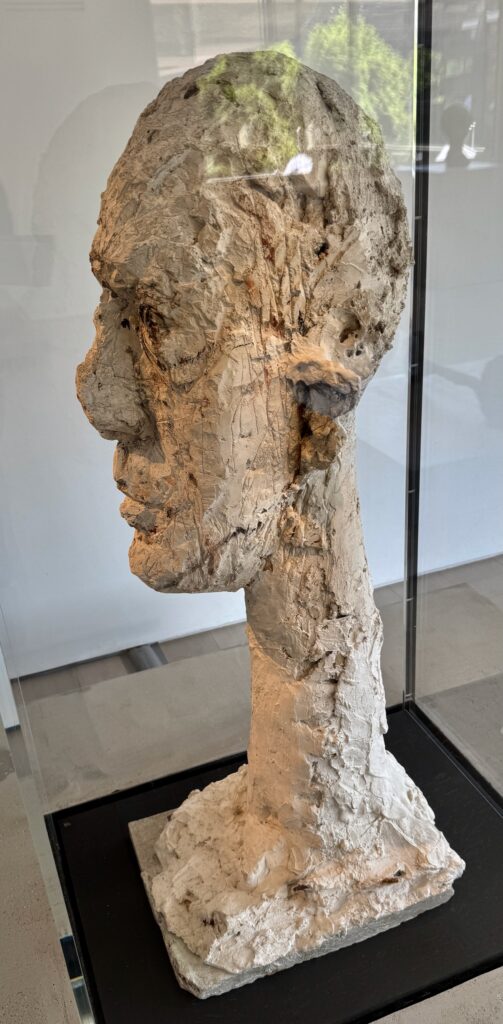

A portriat of Johnson by John Opie (17611807). ‘It depicts Johnson with a “brooding intensity” and “uncompromising directness,” reflecting his character as a prominent figure in English literary criticism. Opie’s work, particularly his portrait of Johnson, is valued for its portrayal of the lexicographer’s character and influence. The portrait, while possibly idealized, stands in contrast to the more realistic depictions by other artists like Sir Joshua Reynolds’ …

James Boswell, whose Life of Samuel Johnson is commonly said to be the greatest biography written in the English language …

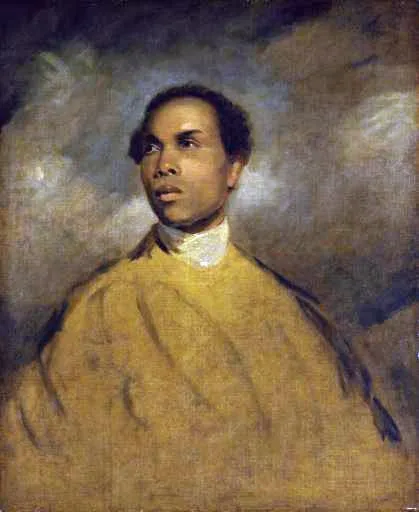

In the front room you will find this portrait, possibly depicting Francis Barber …

Barber was an enslaved Jamaican who arrived at the house, to be Dr Johnson’s servant, in 1752 aged ten. Johnson showed Barber great affection, paid for his education and also remarkably made him his heir. They were friends really rather than master and servant.

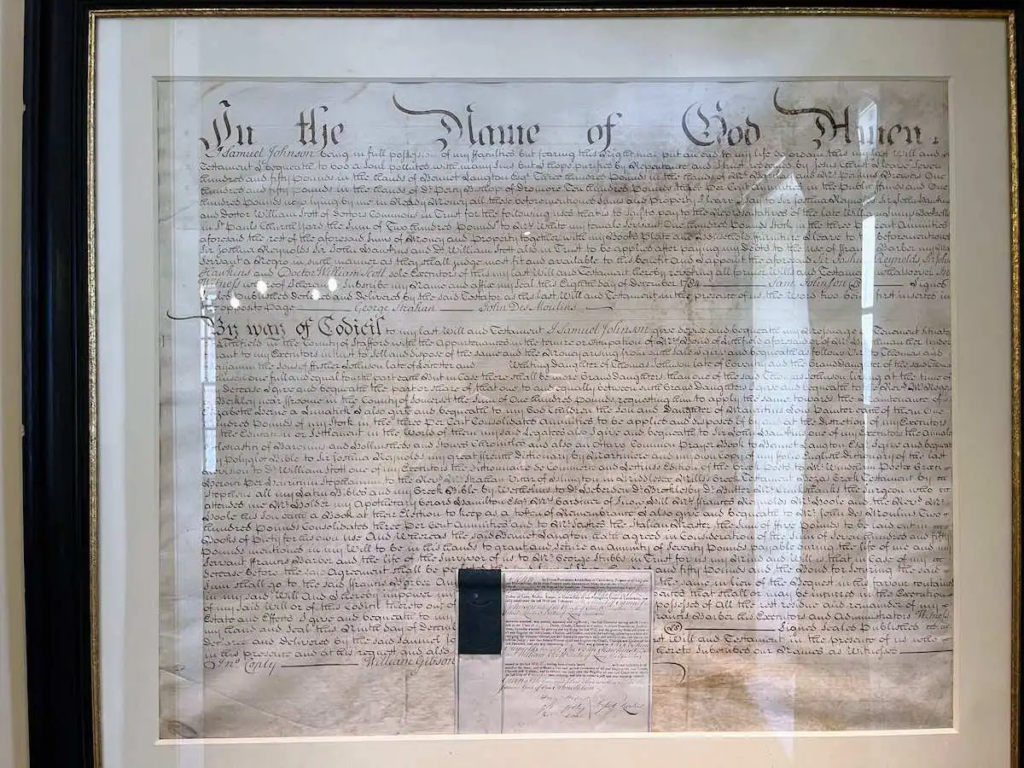

Johnson’s will leaving his trust to Francis Barber, Johnson himself had no direct descendants …

The fine front door (c.1775) complete with anti-burglary devices: a large chain with corkscrew latch, a spiked bar across the fanlight window and two large bolts …

The house is packed with fascinating items telling the story of the great man, his endeavours and the people who knew and worked with him. A highly recommended visit.

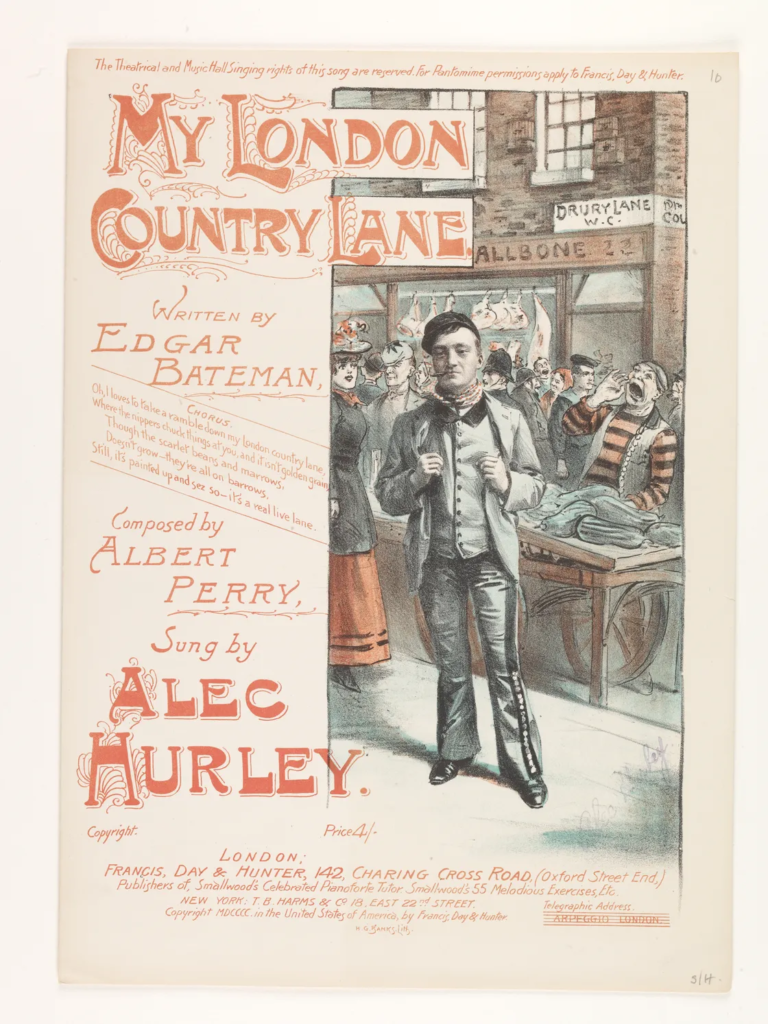

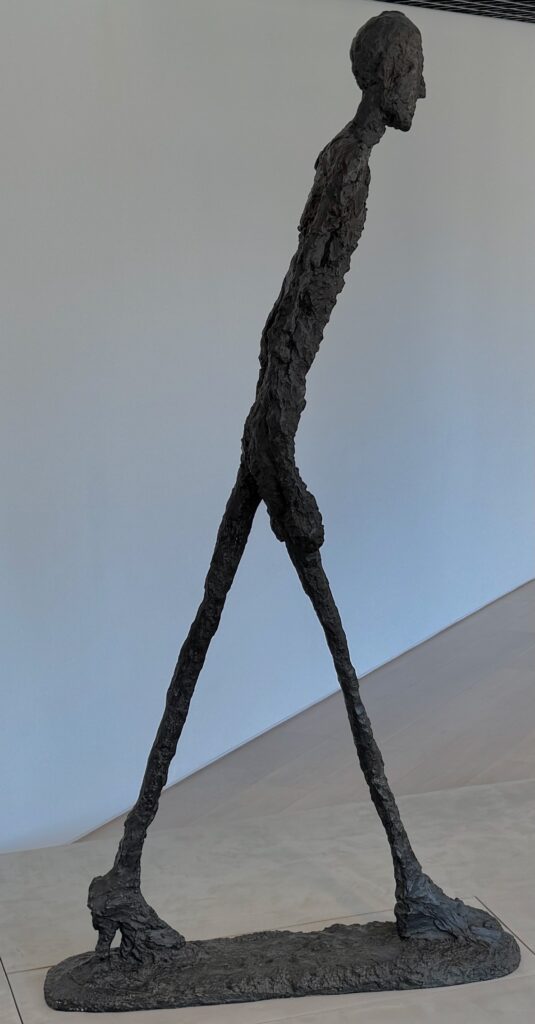

At the other side of the square, facing the house, is Johnson’s most famous cat, Hodge. Here he is remembered by this attractive bronze by John Bickley which was unveiled by the Lord Mayor, no less, in 1997. Hodge sits atop a copy of the dictionary and alongside a pair of empty oyster shells. Oysters were very affordable then and Johnson would buy them for Hodge himself. James Boswell, in his Life of Johnson, explained why:

I never shall forget the indulgence with which he treated Hodge, his cat: for whom he himself used to go out and buy oysters, lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature

People occasionally put coins in the shell for luck and every now and then Hodge is given a smart bow tie of pink lawyers’ ribbon.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …