This lovely church has usually been closed when I have hoped to visit but last week I was lucky enough to drop in thanks to the Friends of City Churches being on duty.

The City once had four churches dedicated to St Botolph, each at one of the City gates, a reminder that St Botolph is traditionally the patron saint of travellers and wayfarers. Three of the churches survive and this is one of them. It is on Aldersgate and its old churchyard at the rear now houses the Watts Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice.

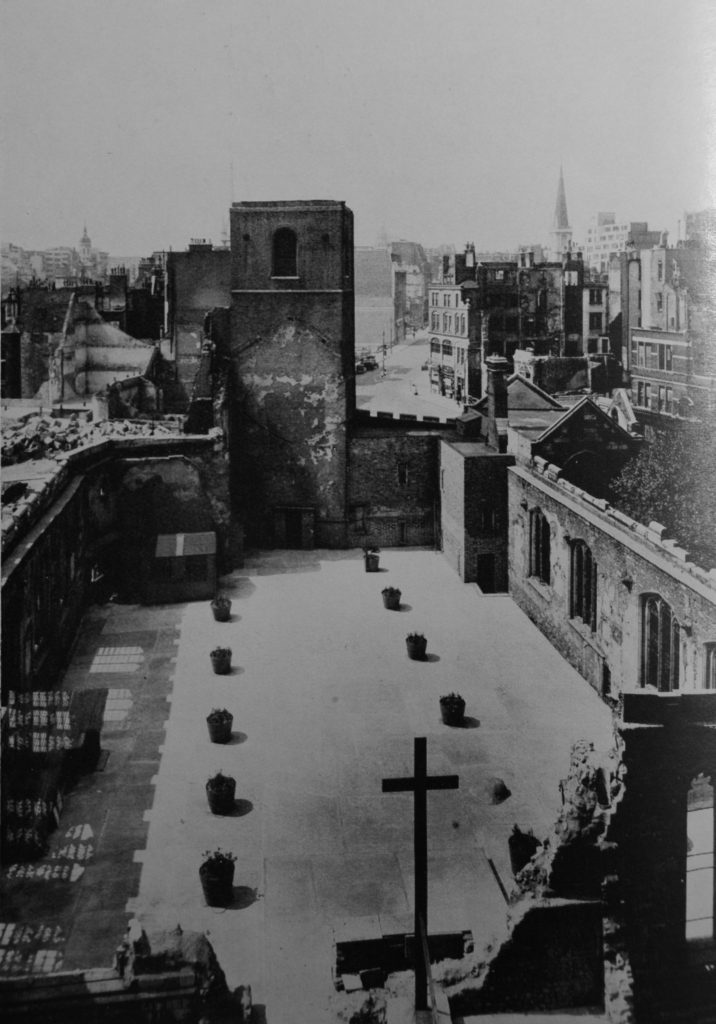

The church as seen from the Barbican Highwalk …

Although it suffered only minor damage in the Great Fire it was rebuilt in 1789-91 by Nathaniel Wright, surveyor to the City. The facade and Venetian window were added circa 1831 after the church had to be shortened for widening of the road. It contains numerous interesting memorials and lots of stained glass. For more about the former I highly recommend the brilliant Bob Speel website from which I will quote extensively in this blog!

Here are my favourites, memorials first.

The most notable is Lady Anne Packington’s Gothic altar tomb of 1563 …

In the recess are brasses of Dame Anne and her (deceased) husband Sir John Packington, and a shield of arms. They kneel facing slightly inwards towards each other, hands raised in prayer, each with their faldstool or prayer desk, with opened book. Sir John wears armour but is bareheaded, with wavy hair down to the shoulders, beard and whiskers; his helmet is placed in front of him. Dame Anne wears a long robe with wide collar, and behind her is a miniature replica, her daughter.

The first of my other favourites is this one of Elizabeth (Hewytt) Richardson who died in 1639 and was the wife of Thomas Richardson of Honningh, Norforlk, who erected the monument …

She had 10 children, seven sons and three daughters, and was ‘a fitt patterne for all women of honor, piete and religion’. Bob Speel comments that ‘the figure faces directly forward with a rather blank, rectangular face, surrounded by curled hair which would seem to be a wig. She wears a curious collar giving a triangular shape to her upper body’.

Mr Speel very much favours the second portrait bust in the church, that of Elizabeth Ashton who died in 1662. It was erected by a daughter, Elizabeth Beaumont …

Mr Speel waxes lyrical as follows: ‘Well, here is something clearly based on the odd Elizabeth Richardson monument noted above, but what a difference in quality. A naturalistic portrait sculpture of the deceased, again facing forward, with a slight smile, wavy rather than curly hair, a tight-fitting cap above, a similar broad collar to the earlier monument but here shaped to the shoulders, and with tassels at the front above the breast. Again a similar pose to the hands, upward turned in front of her; one plump hand supports the other, which holds a book. She has broad sleeves, gathered in at the wrist. Again, an oval niche, squared off surround, and this time a more appropriate top, being simply a swan necked pediment, with painted shield of arms within minor strapwork above.’

Speel identified two two must-see monuments. First, a tall, grey panel to Elizabeth Smith who died in 1750. It contains a poem, beginning ‘Not far remote lies a lamented Fair, // Whom Heav’n had fashion’d with peculiar Care’, and ending sombrely ‘Learn from this Marble, what thou valu’st most, // And sett’st thy Heart upon, may soon be lost.’ It includes a portrait carved in high relief, notable for being a work of the eminent sculptor Louis-Francois Roubiliac …

The second is the largest wall monument, tall enough that a cut-out had to be left in the gallery above. It is to Zachariah Foxall who died in 1758. ‘His portrait can be seen at the top of the monument, a drape held above it by a cherub, with a second cherub seated on the other side, on top of a great boxy casket protruding from the wall. A good example of the more grand, extravagant style of many monuments of around this period, by a sculptor called James Annis, who had his mason’s yard close by in Aldersgate Street itself’ …

Two fine Victorian gentlemen with fine Victorian beards ..

One of three incredible cartouches …

Do try and find a time to visit this church and maybe use Bob Speel’s excellent website to guide you around the numerous monuments of which these are just a small selection.

When it comes to the glass, of particular merit is an impressive window at the east end of the church – not stained glass but a ‘transparency’ (a painting on glass). It is the only one of its kind in the city, painted by James Pearson in 1788. It depicts ‘The Agony in the Garden’ …

By contrast, the stained glass windows are all Victorian or later.

When I saw this one ‘In memory of Matthew Webb’ I thought ‘That name rings a bell …’

Captain Webb was the first man to successfully swim the English Channel. His first attempt was on 12 August 1875 but poor weather and sea conditions forced him to abandon his attempt. Twelve days later, he set off again and, despite several jellyfish stings and strong currents, he completed the swim, which was calculated at 40 miles, in 21 hours and 40 minutes …

One form of celebrity endorsement at the time was to lend your name to a manufacturer of matches …

Tragically, he drowned in 1883 while attempting to cross the Whirlpool Rapids below Niagara Falls. A memorial in his home town of Daley, Shropshire, reads: “Nothing great is easy.”

Some examples of the other windows …

Finally – Lest we forget.

At the east end of the church is a memorial book …

It records the names of nearly 1800 members of the Post Office Rifles who died in action during the Great War, evidence of St Botolph’s connections with the London General Post Office that was once situated nearby.

Some images I have found online (copyrights The Postal Museum) …

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …