On a recent visit to St Mary Aldermary, I took a stroll around the church and was intrigued by this memorial …

I wanted to find out more about this paragon who was ‘Original in Genius, prompt in Judgement, rapid in Decision’, who, ‘whilst he gathered the knowledge of his Predecessors, he perceived their errors and corrected them’. Someone ‘Singularly eminent in his profession’ but also with ‘Private Virtues … his signal tenderness towards his family ‘ and ‘Amiable. Useful. Great’. I liked very much also the tribute to ‘his beloved Wife. The Partner of his virtues and his intellectual endowments’.

Here he is, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds …

Percivall Pott (1714-1788) was born and raised in the City of London. Due to the untimely death of his father before he reached the age of four, it was

thanks to the generosity of his rich relatives that he had the opportunity to fulfil his ambitions. At only 22 years he was awarded the Great Diploma of the Company of Barber Surgeons and by 34 was appointed a fully independent surgeon at St Bartholomew’s, where he remained until

retirement. Today, over 300 years since his birth, he is known as one of the founders of orthopaedics and occupational health.

Pott’s name lives on in a number of conditions that he identified, such as Pott’s disease of the spine and Pott’s Puffy Tumour. The one that initially intrigued me, however, was Pott’s Fracture and how it came to get its name. It was literally by accident!

Here is its story – do please have a read. It speaks volumes about the man himself and the times he lived in.

In January 1756, while on his way to see a patient, Pott was thrown from his horse and sustained an open compound fracture of his lower leg. This is his son-in-law’s account of what happened next …

Conscious of the dangers attendant on fractures of this nature, and thoroughly aware how much they may be increased by rough treatment, or

improper position, he would not suffer himself to be moved until he had made the necessary dispositions. He sent to Westminster, then the nearest place, for two Chairmen to bring their poles; and patiently lay on the

cold pavement, it being the middle of January, till they arrived. In this situation he purchased a door, to which he made them nail their poles. When all was ready, he caused himself to be laid on it, and was carried through Southwark, over London Bridge, to Watling Street, near St. Paul’s, where he had lived for some time—a tremendous distance in such a state! I cannot forbear remarking, that on such occasions a coach is too frequently employed, the jolting motion of which, with the unavoidable awkwardness of position, and the difficulty of getting in and out, cause a great and often a fatal aggravation of the mischief.

After a meeting with some fellow surgeons, it was decided that amputation was the only sensible option and the distinguished patient agreed. Just as the instruments were prepared, however, Edward Nourse (a fellow surgeon and Pott’s mentor) arrived and insisted reduction be tried. Here traction and pressure are applied to the fracture to correct the positioning of the bones.

Pott’s confidence in Nourse and his advice paid off and he subsequently kept his limb without evidence of disability. The reduction approach introduced by Nourse was subsequently refined and became widely used in the treatment of open compound fracture, leading to a substantial decline in amputations. In addition, fractures of the lower leg similar to the type Pott suffered, became known as Pott fractures.

A 1768 medical text book illustration of a Pott fracture …

So what is Pott’s connection with child chimney sweeps?

Being a chimney sweep, or climbing boy as they were often called, was a harsh and dangerous profession. Those employed were often orphans or from impoverished backgrounds, sold into the job by their parents …

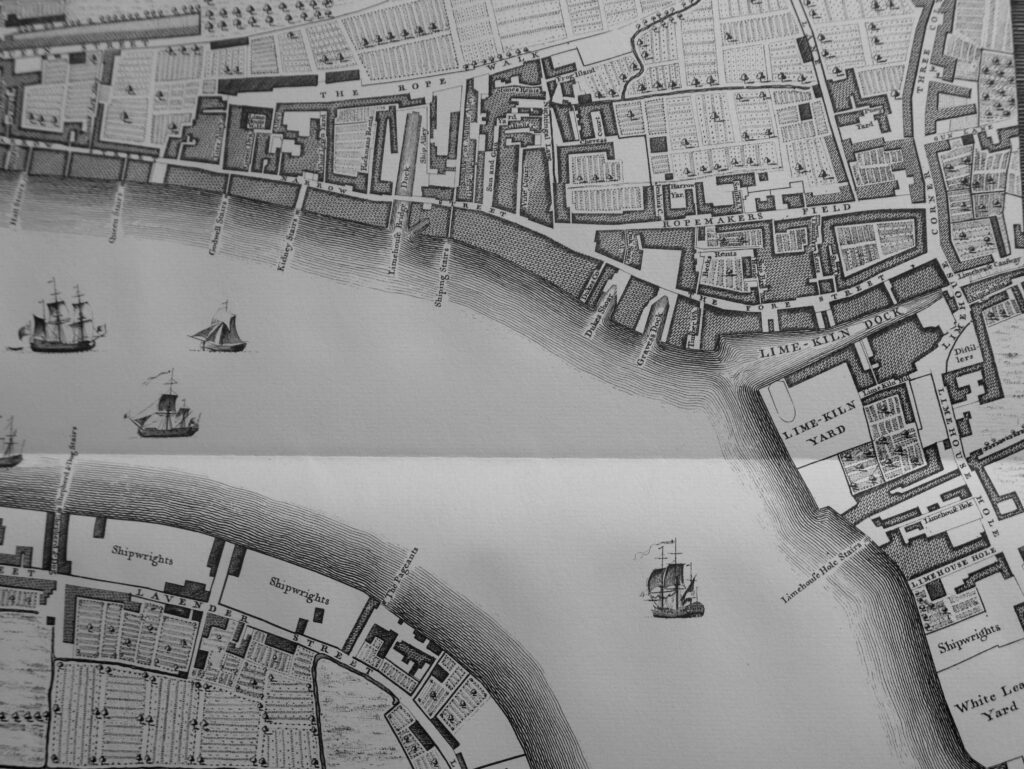

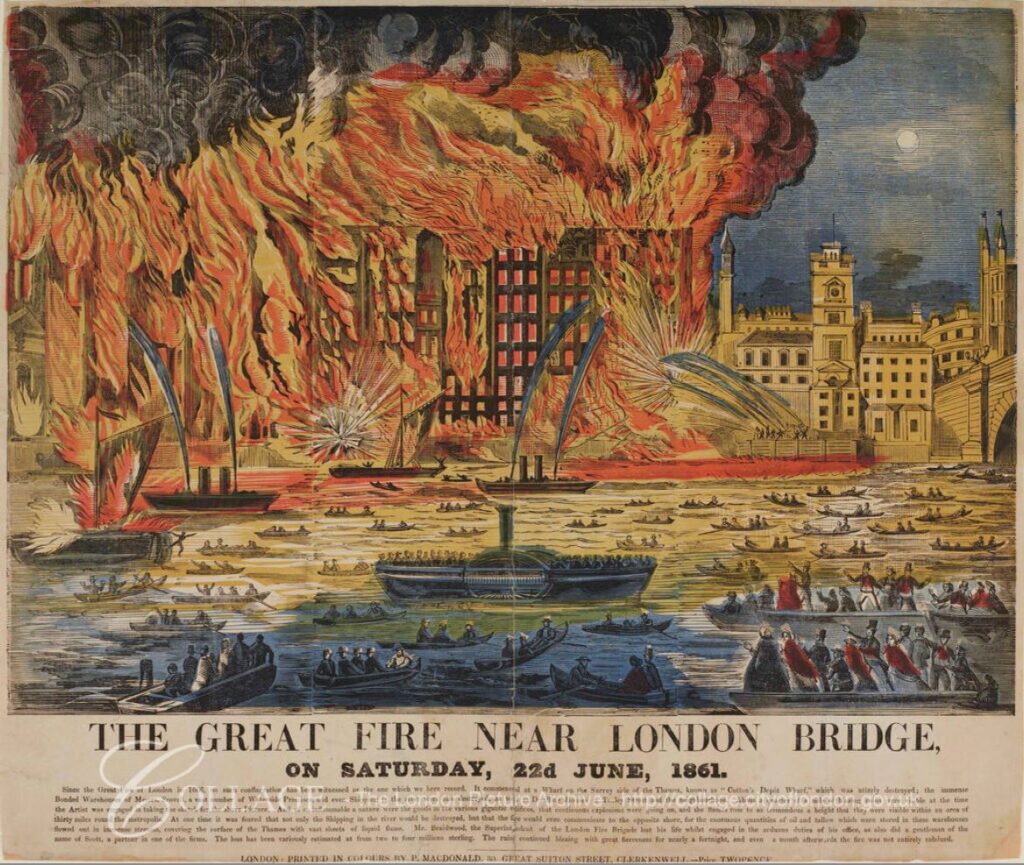

After the Great Fire of London in 1666 buildings started becoming taller, with more rooms that required heating. This, combined with the Hearth Tax of 1662 assessed on the number of chimneys a house had, resulted in labyrinths of interconnected chimney flues. The much narrower and compact design that resulted meant adult sweeps were far too large to fit into such confined spaces. This understandably created a logistical problem as the deposits from the soot required constant cleaning but the space in which to do so was hardly navigable.

Thus, the climbing boys (and sometimes girls) became an essential part of mainstream life, providing a much needed service to buildings across the country.

A Trade Card from 1789 in which he promises he ‘always attends with the Boys himself’. Notice the probable ages of the children! …

I was quite surprised to come across this card, also from the 1700s – a challenge to the stereotype!

This online image is, supposedly, of a teenage sweep ‘apprentice’. Although it doesn’t have a clear attribution it has an authentic look about it …

One legend goes that funeral directors took pity on the young boys and gave them the top hats and coattails of deceased customers. If you book a ‘lucky’ sweep for your wedding he may well turn up wearing the traditional top hat.

Whilst there were variations between buildings, a standard flue would narrow to around 9 by 9 inches. With such a miniscule amount of movement afforded in such a small space, many of the climbing boys would have to ‘buff it’, meaning climb up naked, using only knees and elbows to force themselves up.

The perils of the job were vast, allowing for the fact that many a chimney would still be very hot from a fire and with some still maybe on fire. The skin of the boys would be left stripped and raw from the friction whilst a less dexterous child could possibly have found themselves completely stuck.

The position of a child jammed in a chimney would have often resulted in their knees being locked under their chins with no room to unlock themselves from this contorted position. Some would find themselves stranded for hours whilst the lucky ones could be helped out with a rope. Those less fortunate would simply suffocate and die in the chimney forcing others to remove the bricks in order to dislodge the body. The consistent verdict given by the coroner after the loss of a young life like this was ‘accidental death’.

This is a cross-section of a seven-flue stack in a four-story house with cellars, an 1834 illustration from Mechanics’ Magazine …

The author states: ‘The illustration at ‘E’ shows a disaster. The climbing boy is stuck in the flue, his knees jammed against his chin. The master sweep will have to cut away the chimney to remove him. First he will try to persuade him to move: sticking pins in the feet, lighting a small fire under him. Another boy could climb up behind him and try to pull him out with a rope tied around his legs – it would be hours before he suffocated’.

The death of two climbing boys in the flue of a chimney. Frontispiece to ‘England’s Climbing Boys’ by Dr. George Phillips …

This is what Pott wrote about chimney sweeps in 1775. His compassionate nature shines through …

The fate of these people seems singularly hard; in their early infancy they

are most frequently treated with great brutality, and almost starved with

cold and hunger; they are thrust up narrow, and sometimes hot chimneys,

where they are buried, burned and almost suffocated; and when they get

to puberty, become liable to a most noisome, and fatal disease.

Pott’s work and concern opened the door on a new field of occupational health when he proved an association between an exposure to soot by chimney sweeps in London and cancer of the scrotum: the first time an environmental hazard encountered in the workplace was shown to cause cancer. Many of the climbing boys would get scrotal squamous cell carcinoma, which they called soot wart, in their late teens or early twenties. His publication on the topic in 1775, Chirurgical Observations, also contributed to the creation of the field of epidemiology and the passage of the Chimney Sweepers Act of 1788, which set the minimum age for chimney sweeps at eight years but it was rarely enforced.

Subsequent legislation failed to be effective also and business continued more or less as usual until 1875 when a 12-year-old sweep, George Brewster, got stuck in a chimney and died shortly after. His Master, William Wyer, was found guilty of manslaughter, and widespread publicity incited a fervent campaign for strict regulations. In 1875, a successful solution was implemented by the Chimney Sweepers’ Act which required sweeps to be licensed and made it the duty of the police to enforce all previous legislation – though it was too late for the countless young labourers who had come before.

As will be obvious from the length of this blog, as I researched him more extensively I became a great admirer of Percivall Pott. Not only a great medical man but, by all accounts, a fine person too and quite a character. For example, one biographer states ‘he had a pleasing appearance, and dressed according to the fashion of the period, visiting the hospital in his powdered wig, red coat and buckled sword … he was elegant, lower than middle size. He was an excellent conversationalist with ready wit and a fund of anecdotes’.

On December 27, 1788, he died of pneumonia due to a chill he caught while, against advice, visiting a patient in severe weather 20 miles from London. His last conscious words were: “My lamp is almost extinguished; I hope it

has burnt for the benefit of others.” It certainly had.

At some point his gravestone was moved from inside the church to just outside the west door where now, sadly, folk walk across it not realising the distinguished person it commemorates …

The inscriptions are very worn but I have established what they say and they form an interesting record of some of Percivall’s descendants. Here they are …

PERCIVALL POTT F.R.S. died 27 December 1788. Aged 75

MRS SARAH FRYE, his eldest daughter, died 27 October 1791, aged 41

Mrs. MARY LITCHFIELD, eldest daughter of J. R. FRYE and above SARAH and wife of H. C. LITCHFIELD, died 22 January 1806, aged 31

Mrs SARAH POTT, relict of above, died 18 January 1811, aged 87

Miss MARY LITCHFIELD, second daughter of RICHARD LITCHFIELD, of Torrington, co. Devon, died 1 March 1811, aged 27

PERCIVALL POTT, eldest son of above PERCIVALL, died 27 January 1833 aged 83

SARAH FRYE. Daughter of J. R. FRYE and grand-daughter of PERCIVALL POTT, senr., died 9 March 1844 aged 69

Ven. JOSEPH HOLDEN POTT, M.A. Chancellor of Exeter, and late Archdeacon of London, died 17 February, 1847, aged 88

I am indebted to the historian Jessica Brain for her article about the climbing boys which I have drawn on extensively for this blog. You can read the full article here. You can also read an excellent short biography of Percivall Pott here in the Who’s Who in Orthopedics Journal. For a really deep analysis of the climbing boys and the campaigns to help them I recommend the 2010 doctoral thesis by Niels van Manen PhD, which you will find here.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …