Before Melania Trump arrived in the White House, only one US President’s wife had been born outside America – read on to see who she was.

My first visit was to the Bank of England Museum in Bartholomew Lane EC2. Interactive exhibits mean you can have a go at setting monetary policy or try to navigate some tricky financial crises. It’s a great museum but unfortunately many of the exhibits (such as the building’s architectural development) are not easily photographed so you will have to visit in person to see more.

Among the fun things you can do there is to reach into a box and try to pick up a 13 kilo (28 lb) gold bar …

It’s 99.79% pure gold.

There are some fascinating documents including …

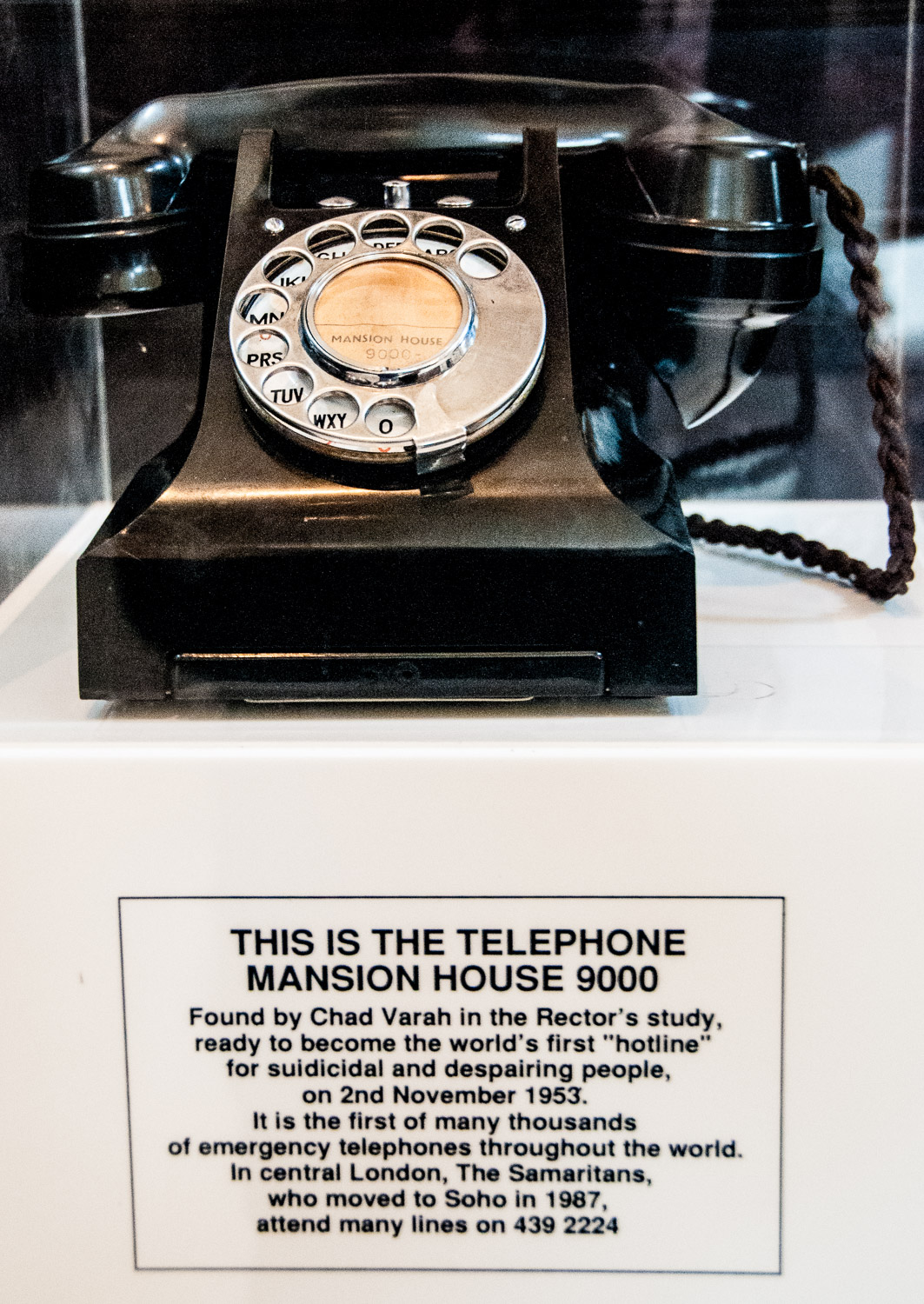

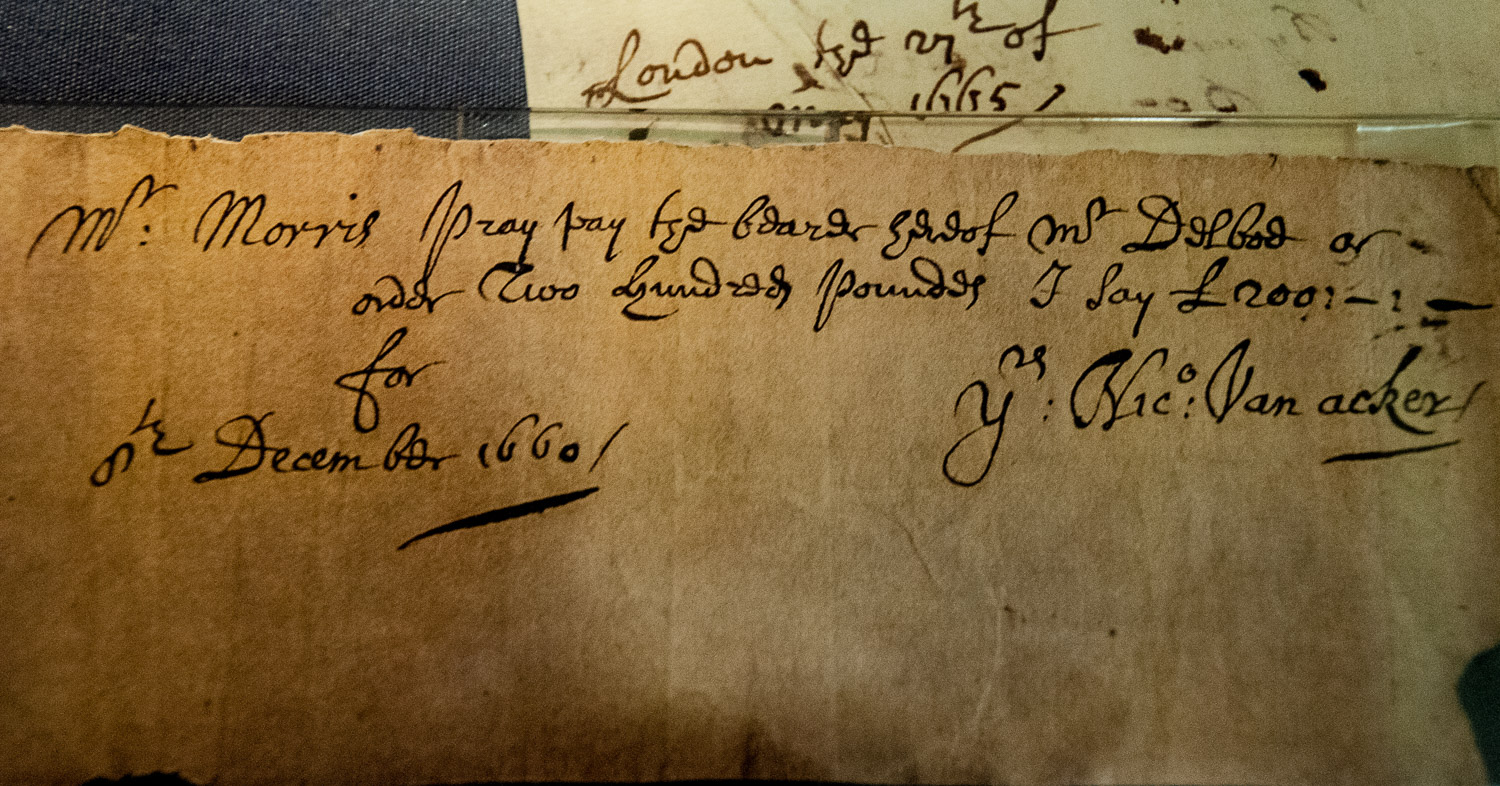

A very early cheque dated 8 December 1660.

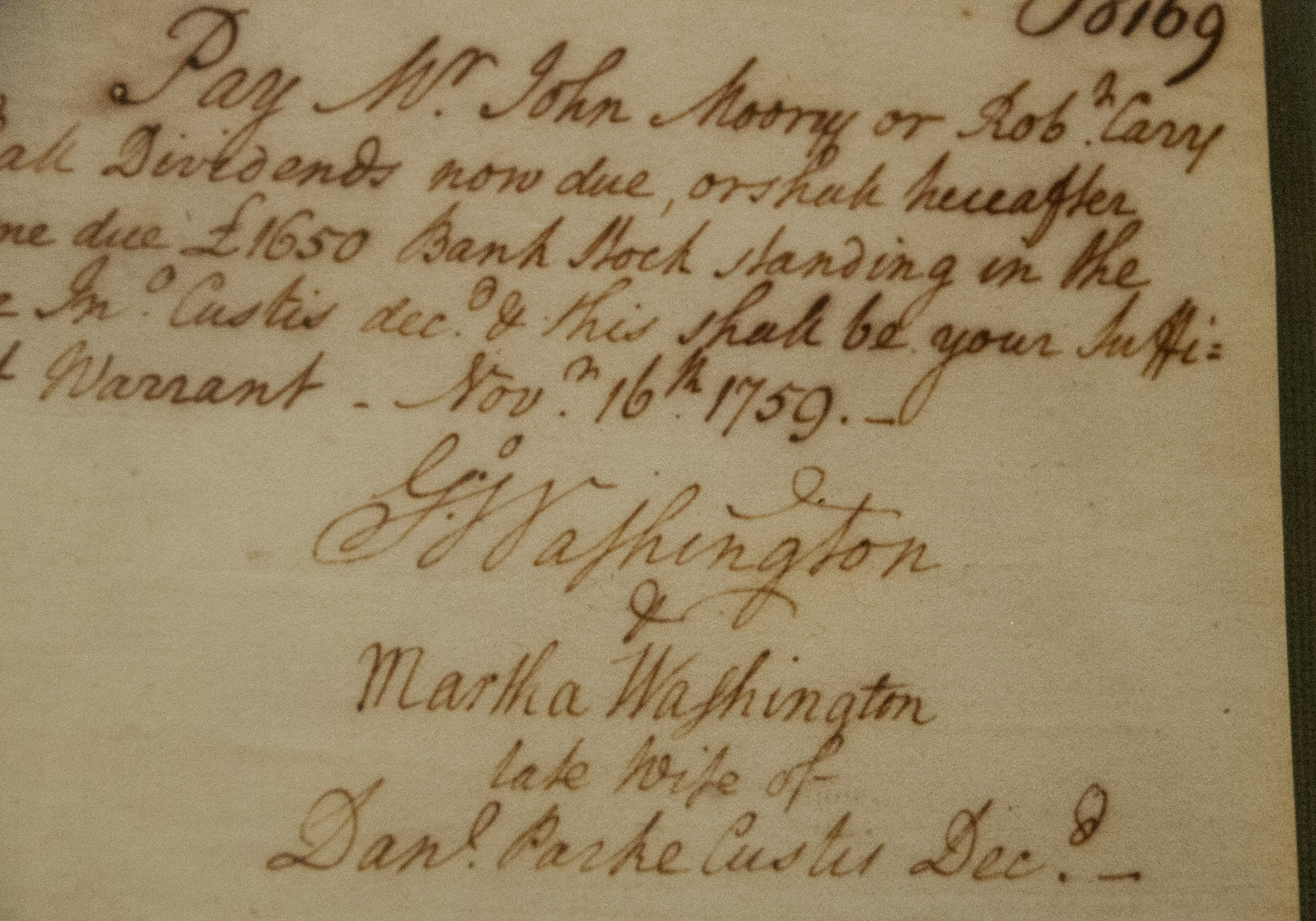

A document signed by the first President of the United states, George Washington, and his wife Martha …

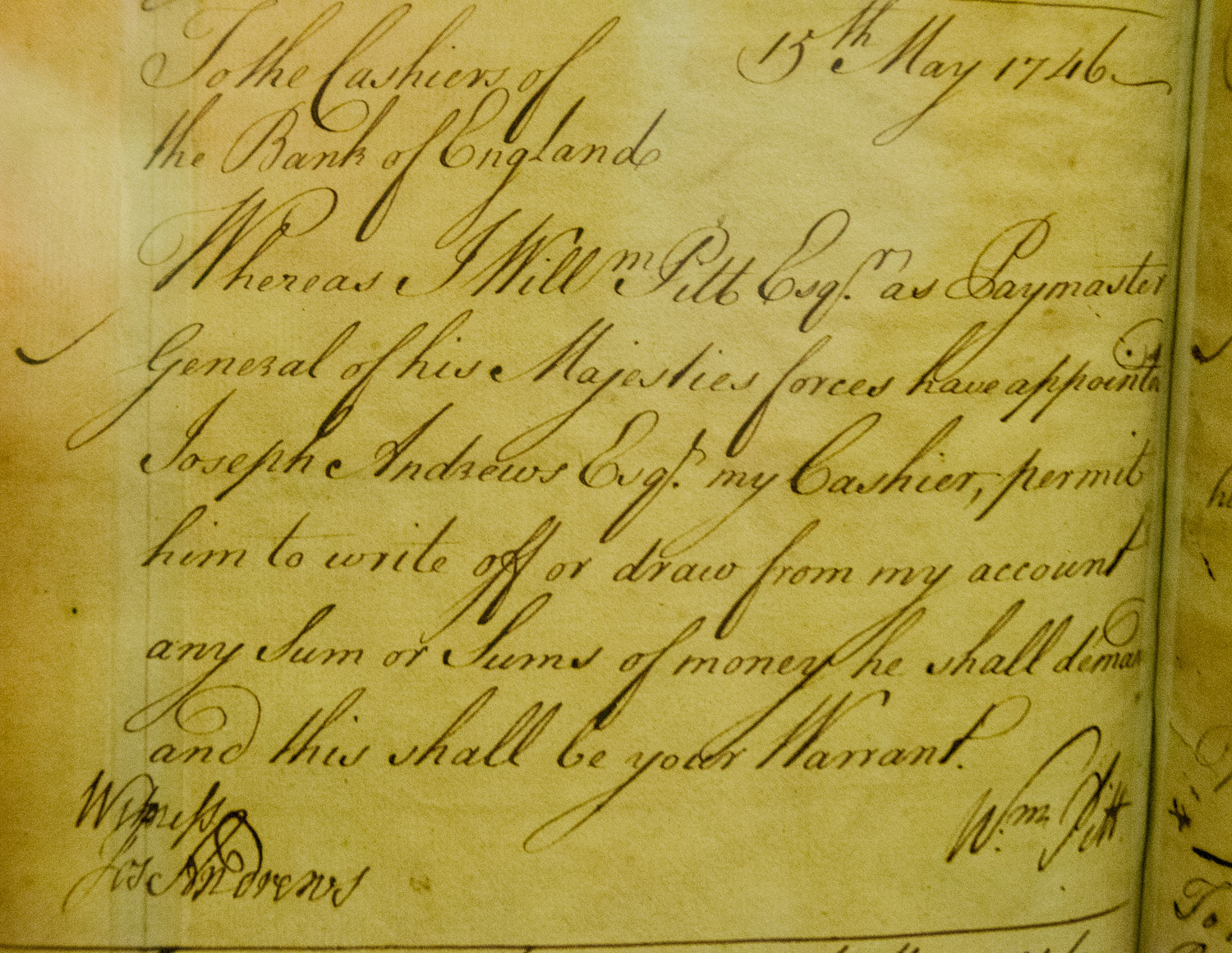

The signature of William Pitt the Elder …

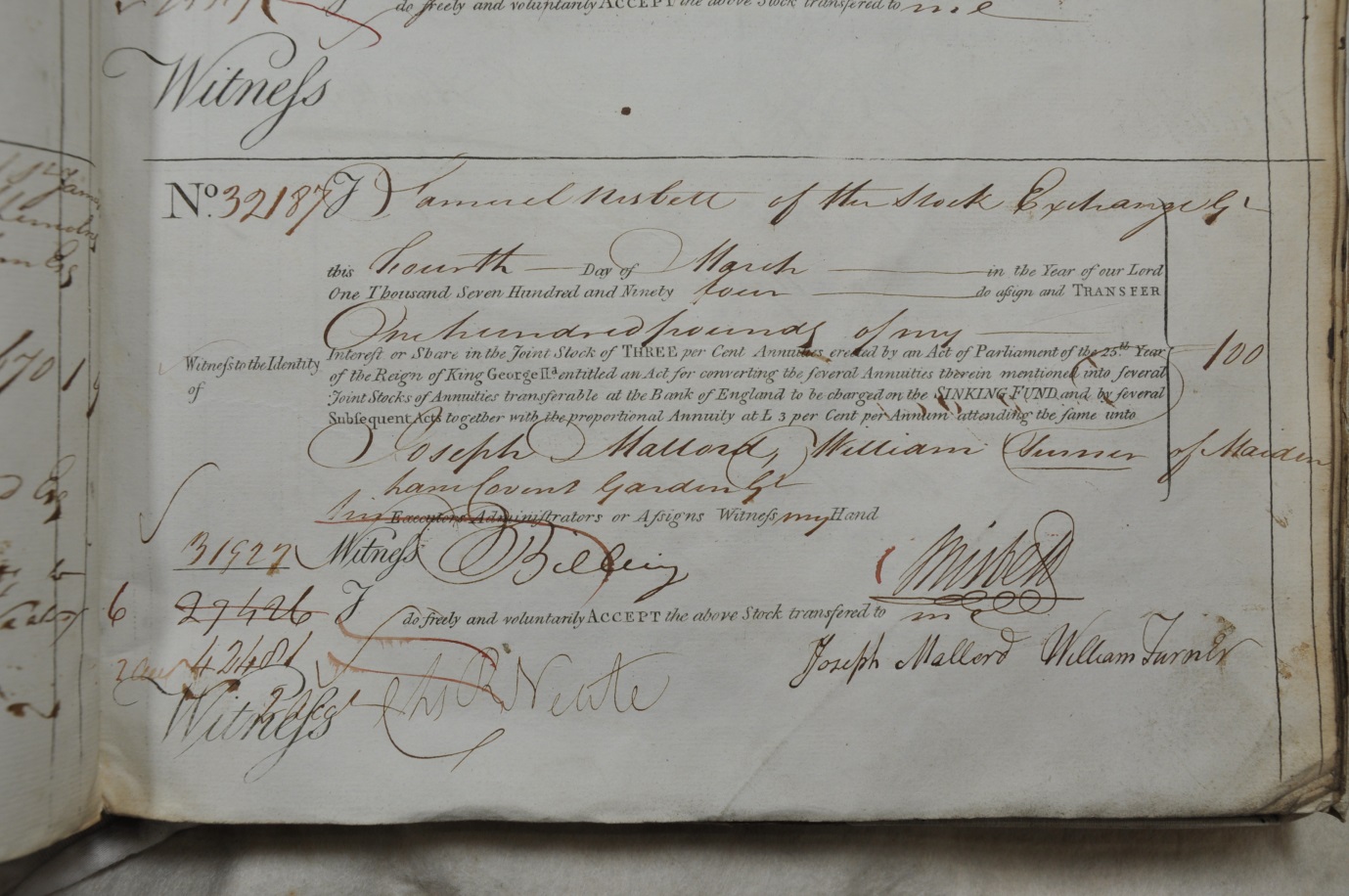

And J M W Turner …

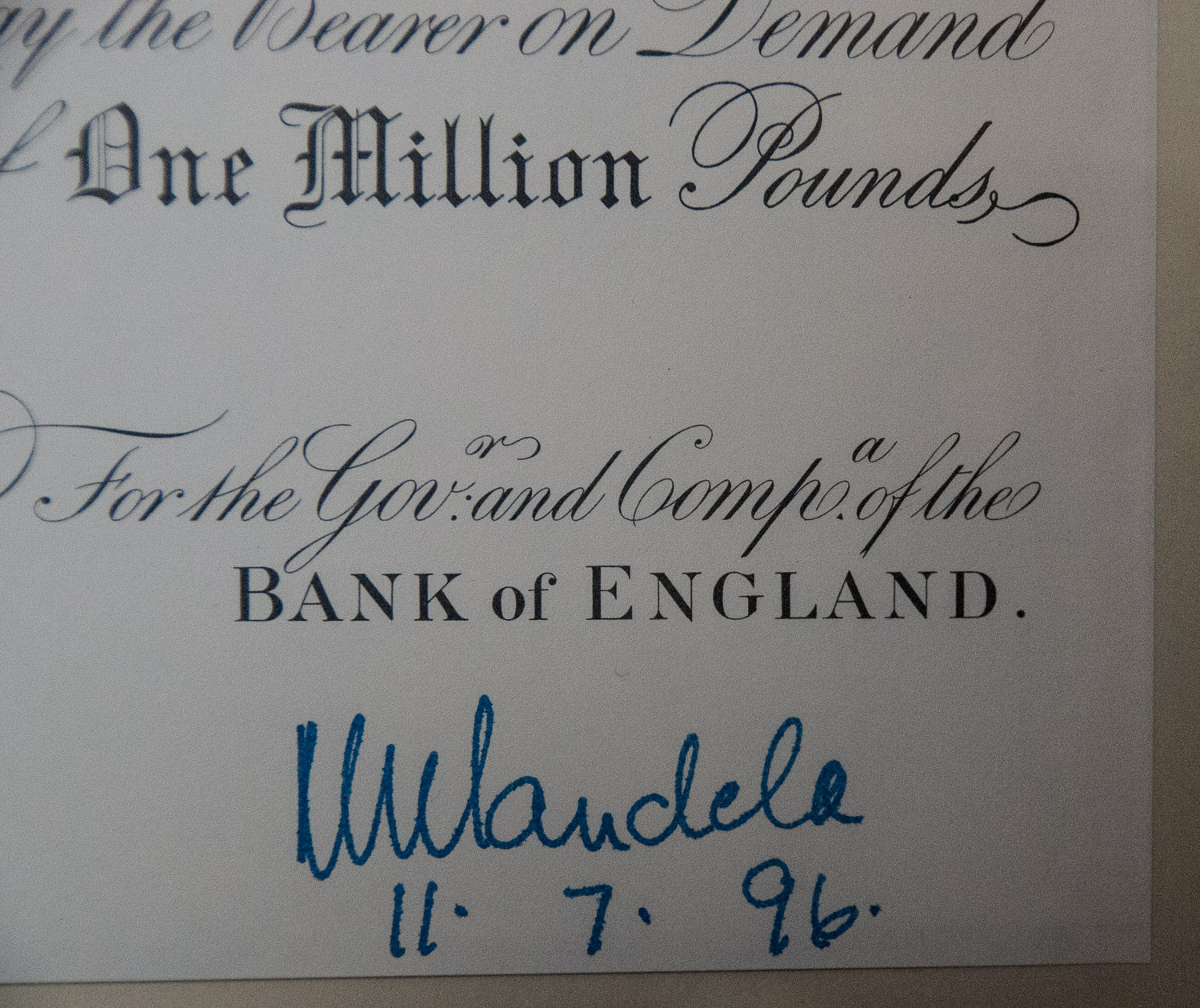

And finally a memento of when Nelson Mandela briefly became the Bank’s Chief Cashier when he was a guest in 1996 …

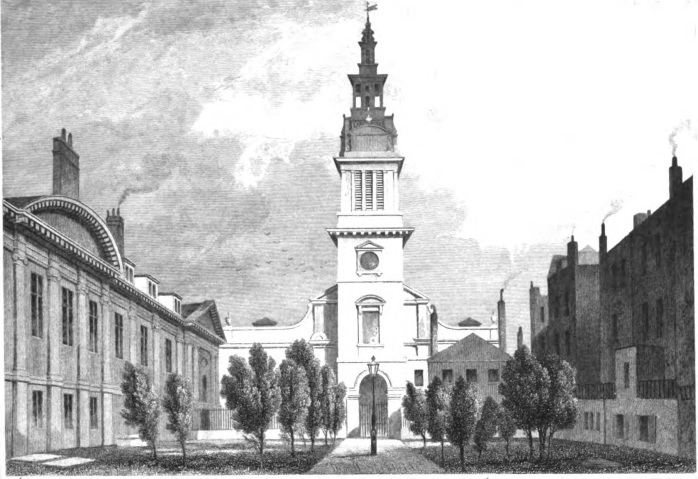

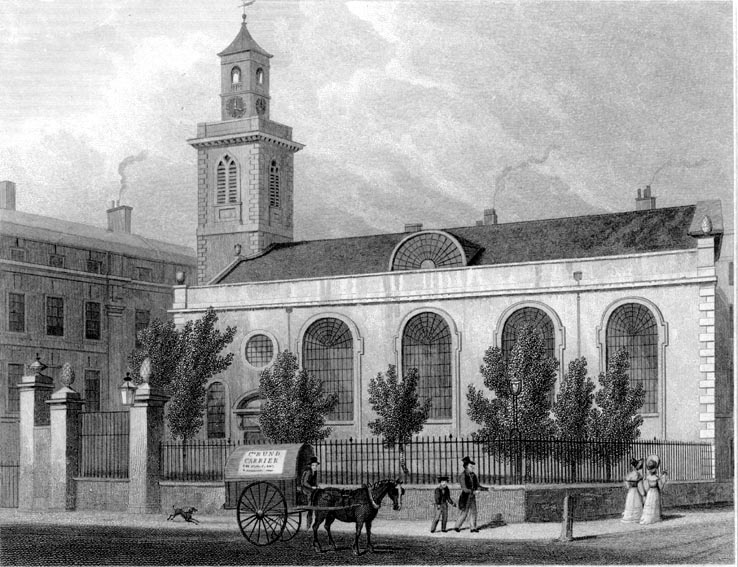

My next visit was to the Crypt at All Hallows-by-the-Tower on Byward Street EC3. The church was seriously damaged during the War but has now been beautifully restored and, when you have had a look around, head downstairs to the crypt. Here, in what is part of the original Saxon church, you will find the original crow’s nest from a ship …

Photo by A London Inheritance.

The Quest sailed from 1917 until sinking in 1962 and was the polar exploration vessel of the Shackleton–Rowett Antarctic Expedition of 1921-1922. It was aboard this vessel that Ernest Shackleton died on 5 January 1922 while the ship was in harbour in South Georgia.

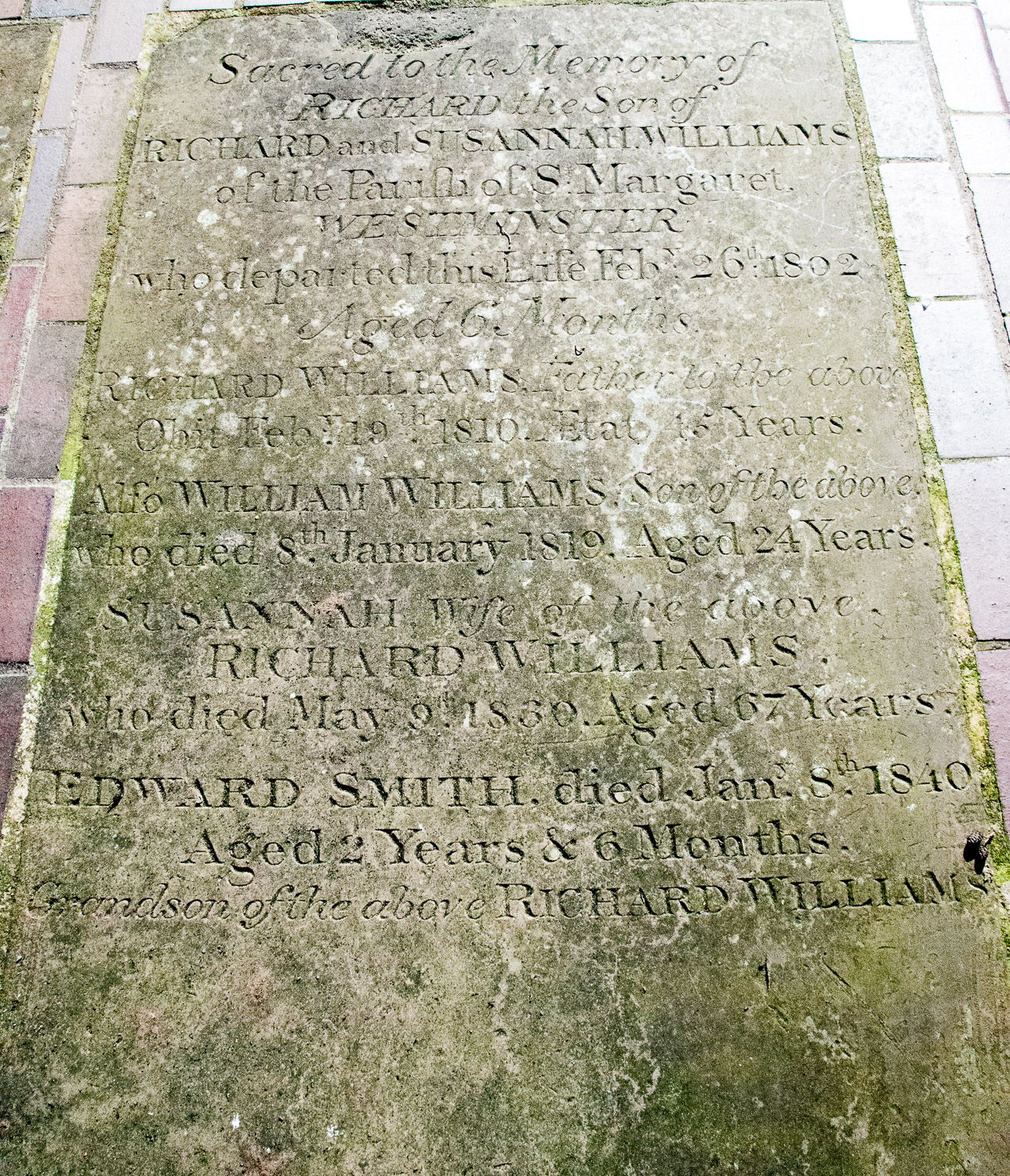

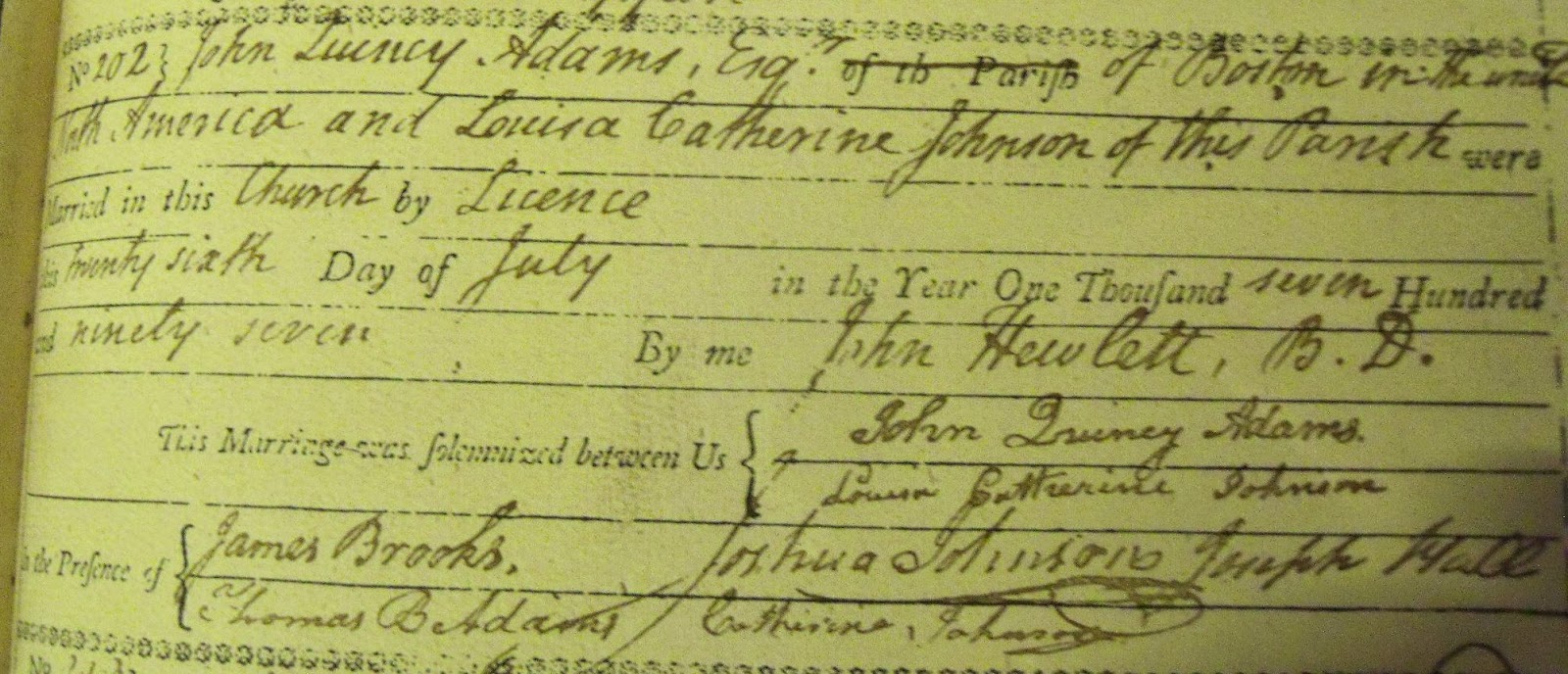

Nearby is displayed the marriage certificate dated 26 July 1797 of John Quincy Adams, later to become the sixth President of the United States. It was his wife Louisa, a local London girl, who was the only foreign born first lady of the United States until the arrival of Melania Trump.

Also in the crypt are remains of the floor of a second or third century Roman house, including part of a corridor and adjacent rooms …

Beneath the present nave is the undercroft of the Saxon church containing three chapels: the Undercroft Chapel, the Chapel of St Francis of Assisi and the Chapel of St Clare.

The Undercroft Chapel. Picture by A London Inheritance.

The Undercroft Chapel is constructed out of the former ‘Vicars’ Vault’, and is now a columbarium for the interment of ashes of former parishioners and those closely associated with the church.

The pretty St Clare chapel stained glass.

Since this year marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War, I will end this blog with these three crosses removed from World War I battlefields and which can be seen in the museum …

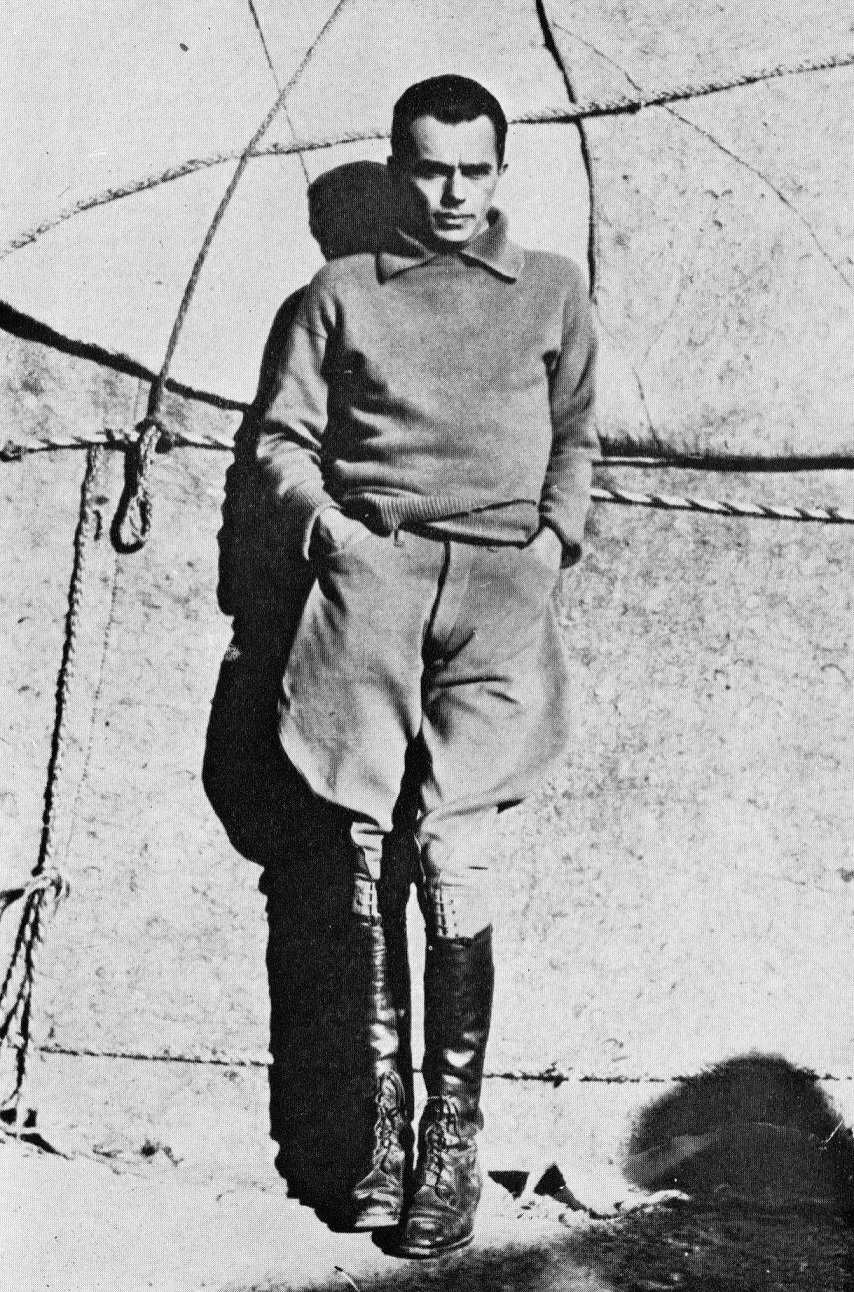

I have done some research on the three men but have only been able to find a picture of one of them.

On the left, Major B. Tower, MC and bar, mentioned in dispatches three times and now buried at Bellacourt Military Cemetery in the Pas-de-Calais. The Edinburgh Gazette of 18th September 1918 remarks that he was remembered ‘for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Under heavy machine gun and artillery fire he made several reconnaissances and brought back valuable information to various commanding officers. He showed great energy and determination.’

The cross on the right marked the grave of W. C. V. Pepper, a Private in the 1/24th London Regiment and previously the East Kent Buffs. He is buried in Railway Dugouts Burial Ground in West Flanders, Belgium – he was 20 years old and died on New Year’s Day 1917.

In the centre 2nd Lt. G.C.S Tennant. His last letter home was found unposted on his body after his death. It reads:

Sept. 2nd 1917.

Dearest Mother,

All well I come out tonight. By the time you get this you will know I am through all right. I got your wire last night, also your three letters. Many thanks for that little book of poems. It is a great joy having it out here. There is nothing much to do all day except sleep now and then. It will soon be English leave, and that will be splendid! I got hit in the face by a small piece of shrapnel this morning, but it was a spent piece, and did not even cut me. One becomes a great fatalist out here.

God bless you, your loving Cruff.

He was killed later that night, at about 4.00 am, and is now buried at Canada Farm Cemetery. He was 19 years old.

George Christopher Serocold Tennant (1897-1917).

After his death one of his men attested:

‘He was specially loved by us men because he wasn’t like some officers who go into their dug-outs and stay there, leaving the men outside. He had us all in all day long … The men would have done more for him than for many another officer because he was so friendly with them and he knew his job. He was a fine soldier, and they knew it.’