Just across the road from Tower Hill Underground Station is one of London’s finest architectural landmarks, the former Port of London Authority (PLA) building on Trinity Square.

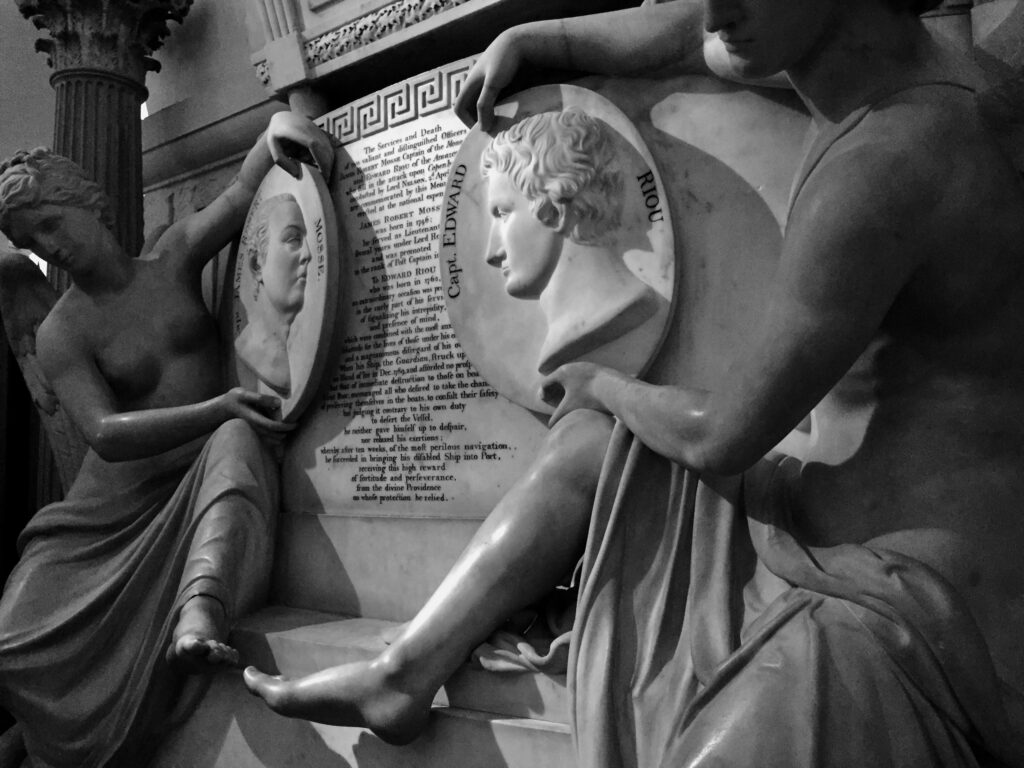

It towers over Trinity Square Gardens, home of the Mercantile Marine Memorial to the Merchant Seamen who died in both world wars …

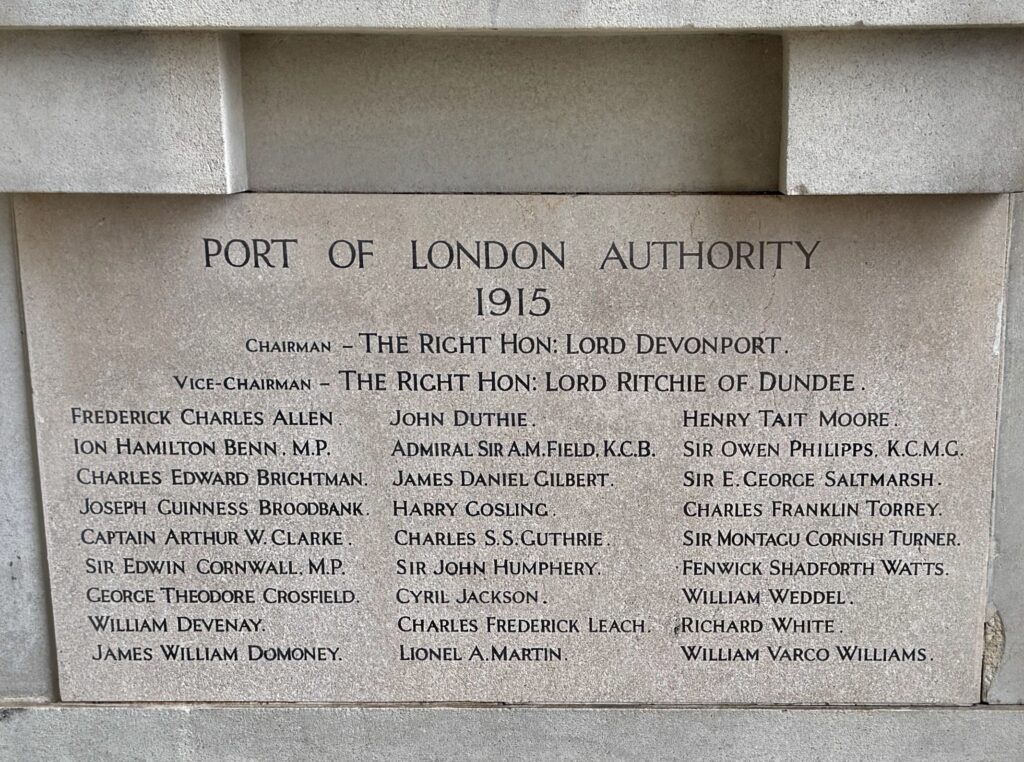

The old PLA headquarters harks back to the great days of Empire and global trade. The ‘Great and the Good’ gathered to lay commemoration stones a few years after building work commenced in 1912 …

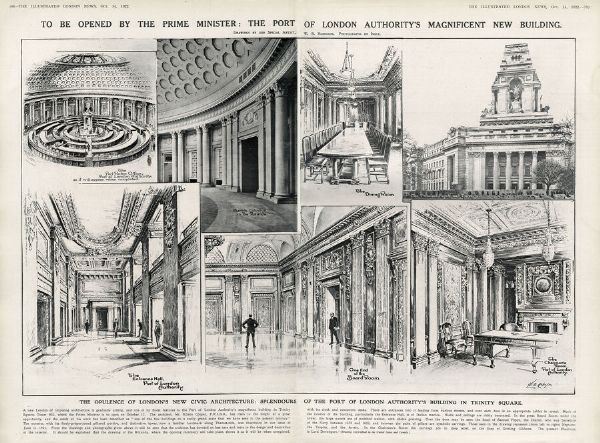

The inauguration of the building by Prime Minister Lloyd George in 1922 was reported as an event of national importance. The creation of a unified Port Authority in 1909 had been facilitated by an Act of Parliament, the organisation being set up to Protect the Port of London from the increasingly destabilising effect of competition between rival dock companies …

The grand classical entrance features four Corinthian columns. It is three storeys high and topped by a massive tower with a giant figure that would have been clearly visible from the river…

Old Father Thames stands triumphantly, holding his trident and pointing

east, paying homage to the prosperity of trade between nations. The

trident, his lush beard and the anchor at his feet associates Old Father

Thames with Poseidon/Neptune – the Greek/Roman god of the sea – and

shows how classical symbolism was used to into the 20th century to

celebrate London’s influence over global maritime trade …

On the west side of the tower, within a galleon drawn through the waves by two sea horses, there stands a winged, nude male figure. He symbolises ‘Prowess’ and weilds a large antique oar …

On the east side is ‘Agriculture’, personified by a winged female figure with a flaming torch in her hand drawn in a triumphal chariot by two oxen. The beasts are lead along by a youthful male figure representing ‘Husbandry’ …

At street level is ‘Commerce’. A bearded male figure holds the scales of trade and a basket of merchandise. Before him is the lamp of truth …

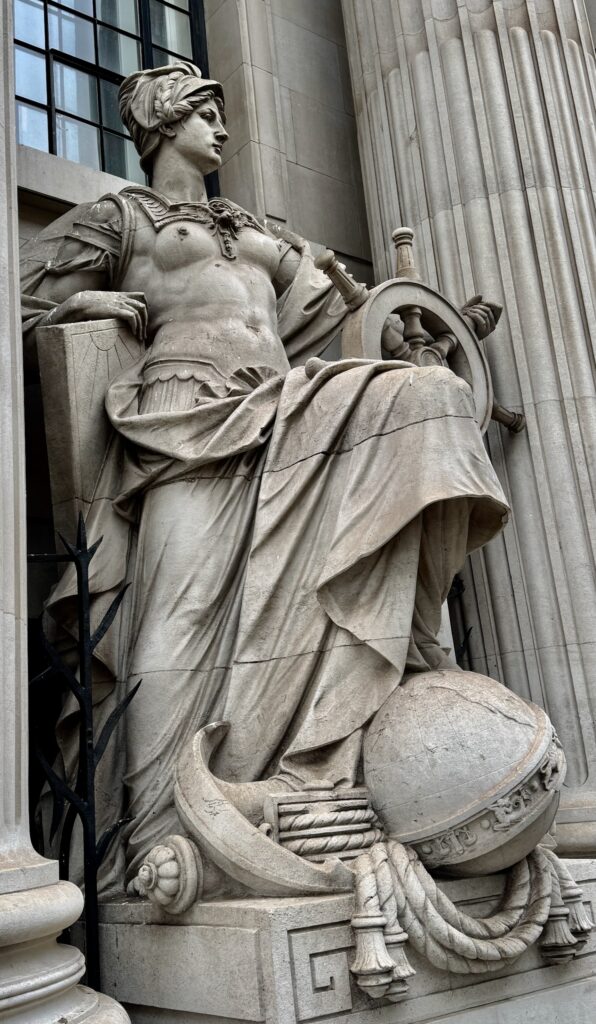

‘Navigation’ is represented by a young woman with one hand on a ship’s wheel and the other holding a chart. Her foot rests on a globe and around her are the symbols of shipping …

Resting against elaborate lampposts outside the main entrance are two rather plump cherubs …

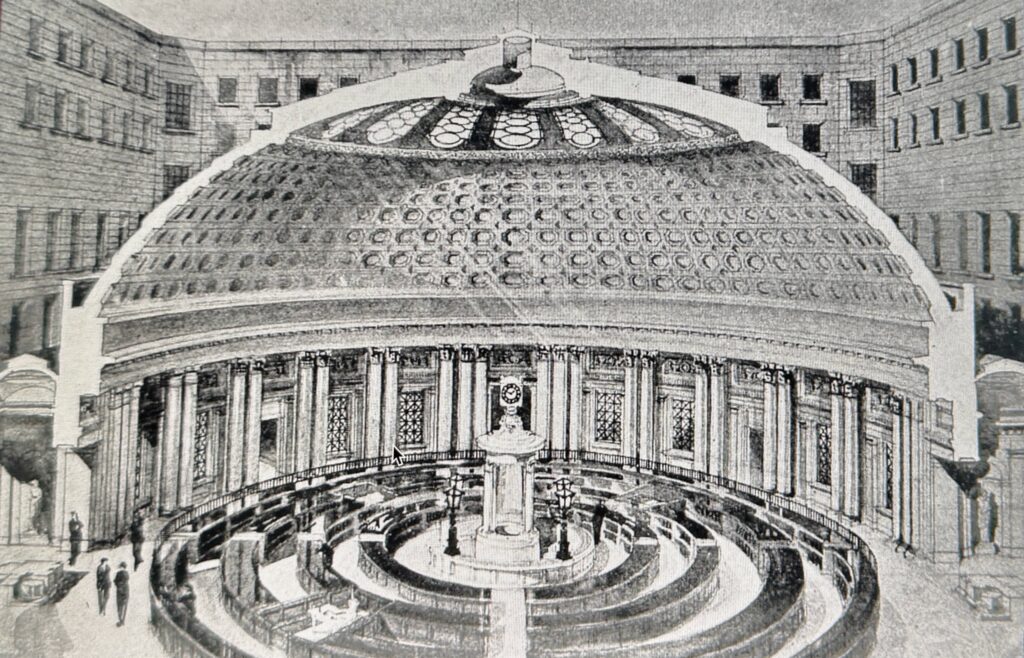

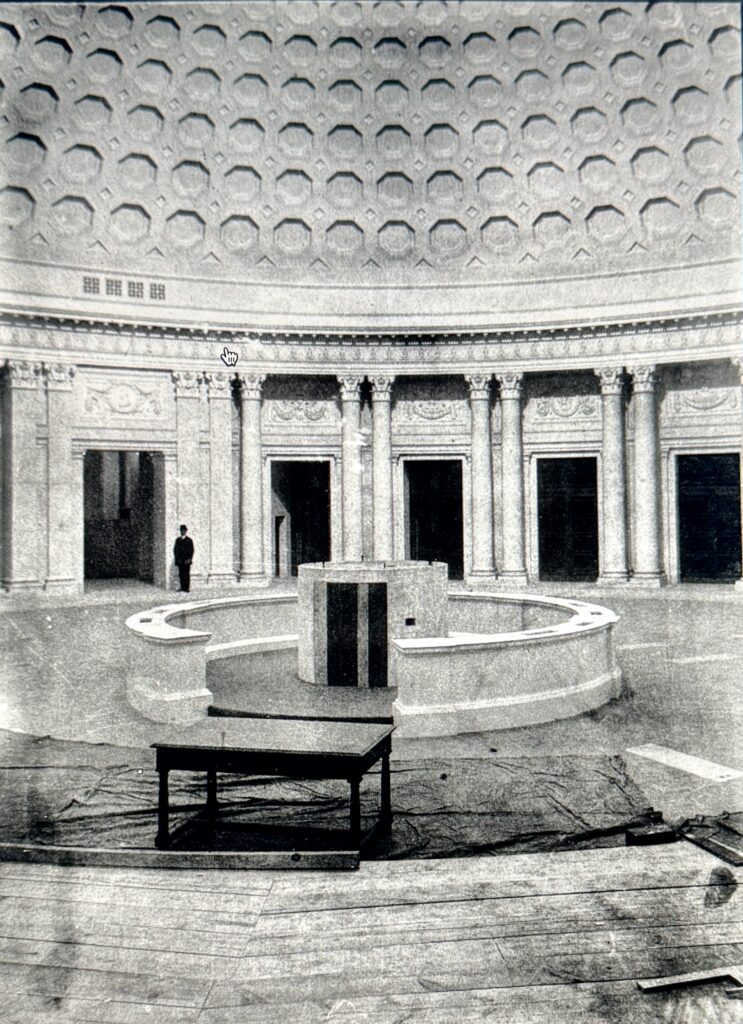

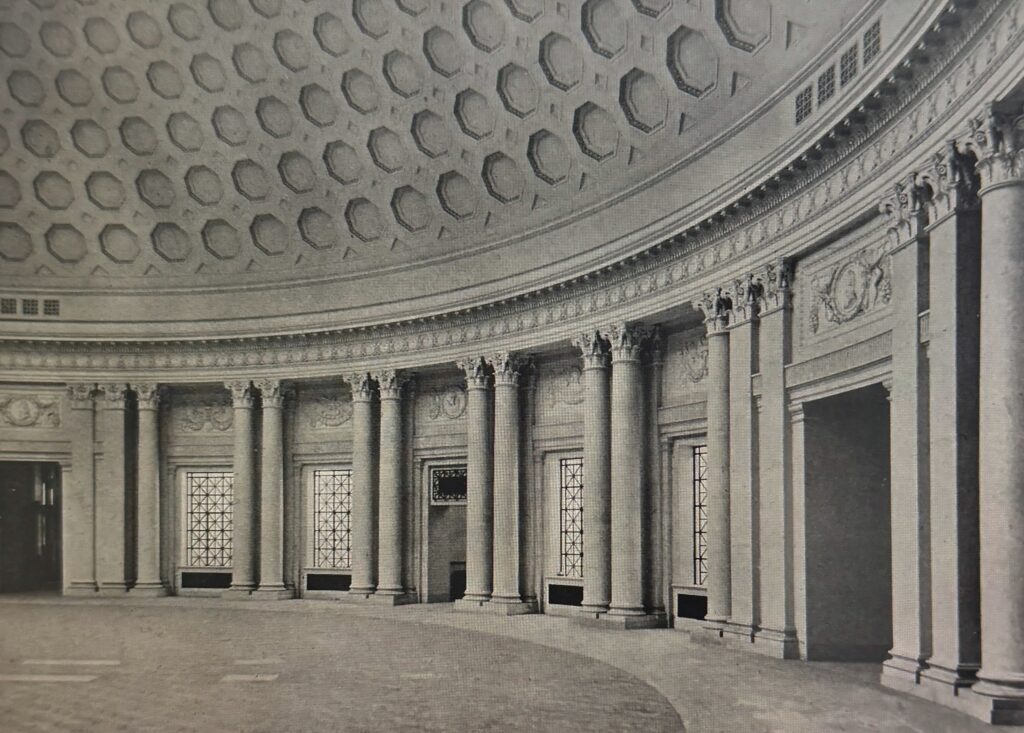

Inside the original building was a spectacular rotunda topped by a magnificent glass dome, created to emulate that of St. Paul’s Cathedral. This was totally destroyed in the World War II Blitz and I have only been able to find four images giving some idea of what it looked like …

The front of the building after the bombing …

In the 1970s, after the Port of London Authority moved to its current location in Tilbury, the building was renovated and the central courtyard was filled in with office space. It was then occupied by the European headquarters of the insurance broker Willis Faber Limited and continued to serve as offices until 2008. When Willis Faber moved on to a new location, the building lay vacant for several years.

It was purchased in 2010 by Reignwood, a Chinese investment company, and is now a Four Seasons Hotel. I must say, it really does look splendid.

Inside the main doors …

The rotunda has been reimagined …

It’s open to non-residents for drinks and snacks.

By the way, the 1946 reception of the first general assembly of the United Nations was hosted here in what is now known as the UN Ballroom. The occasion was attended by (among others) King Faisal of Saudi Arabia and US first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. From its second-floor location, the room’s windows overlook the Trinity Square Gardens and beyond to the Tower of London and Tower Bridge. It’s available to book for events …

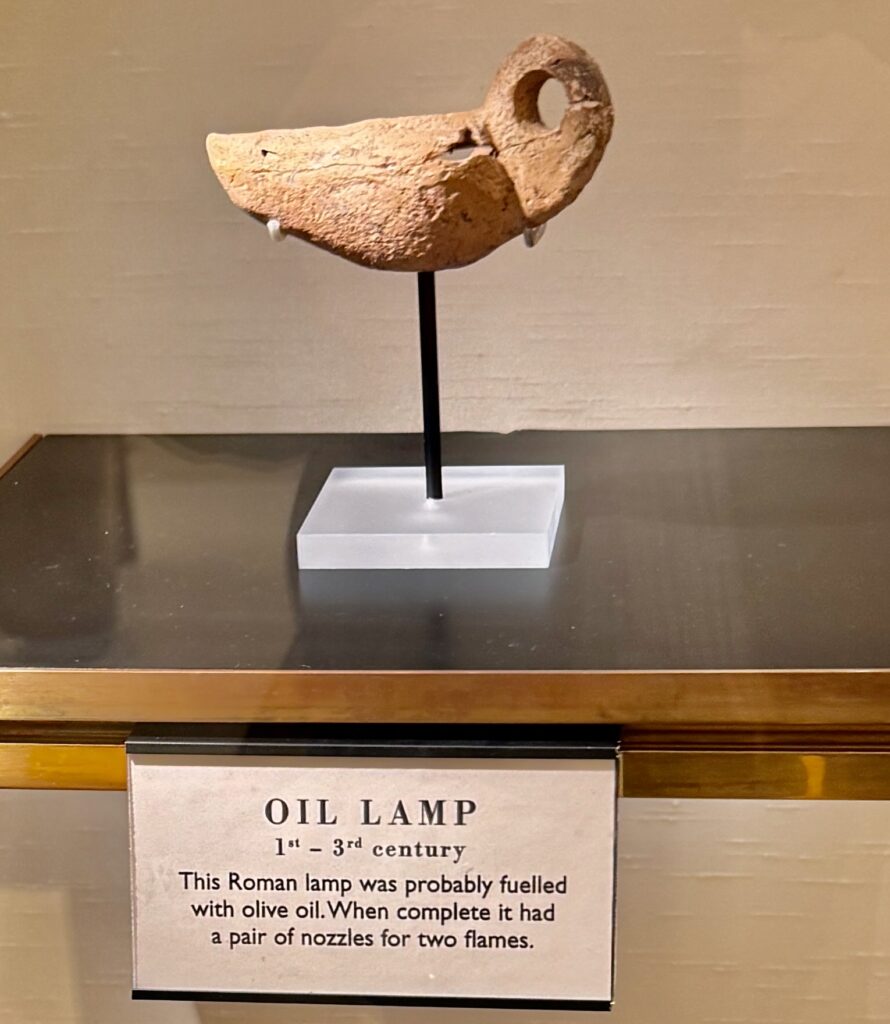

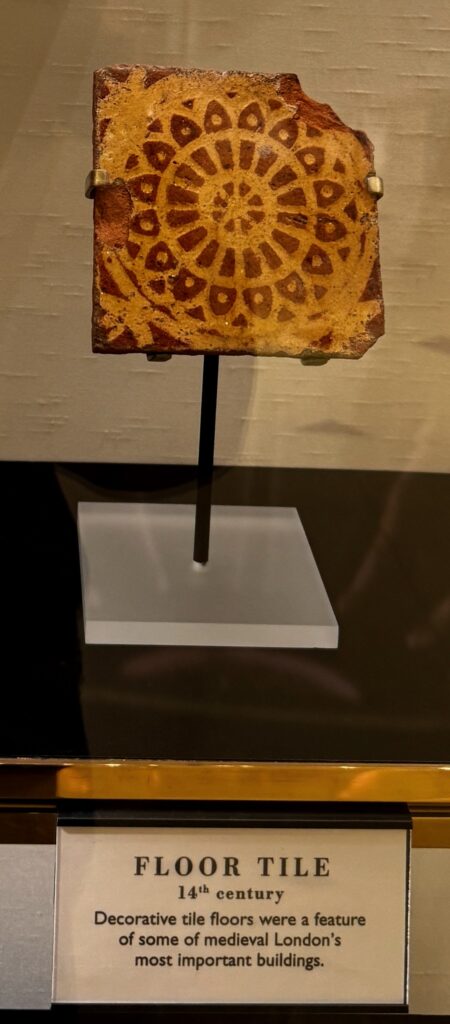

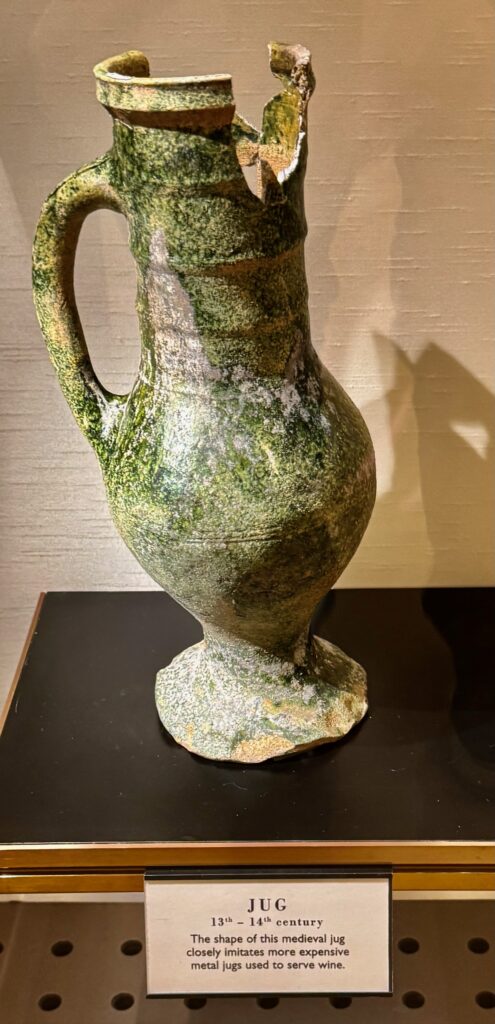

The Museum of London Archaeology practice were given access to the site during redevelopment and a selection of the artefects they discovered are on display in the reception area. These are just a few of the exhibits – it’s well worth popping in to the hotel to have a look …

Now something readers more my age will remember!

The Professionals was a TV series that ran from 1977 to 1983 featuring Bodie and Doyle, senior agents of the British intelligence service CI5 (Criminal Intelligence 5), and their handler George Cowley, fighting terrorism and similar high-level crimes. The PLA building appears in the opening sequence of the second series.

Watch it in full here, including music – volume up! : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=55gpif0a0P8

Some stills from the sequence …

The famous railings they stride past are still there …

It’s worth walking round to the north side of the building which is also impressive …

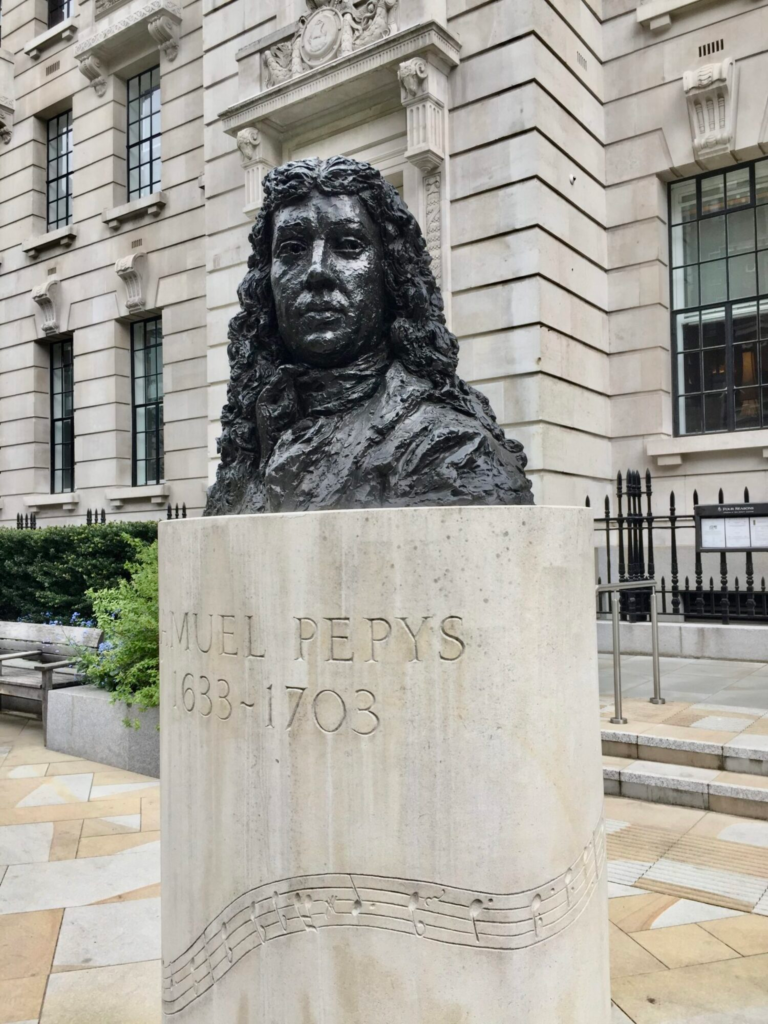

You can just about make out a plinth in front of the building. It’s a bust of one of my heroes, the diarist and brilliant naval administrator Samuel Pepys …

The music carved on it is the tune of Beauty Retire, a song that Pepys wrote. The garden in which it stands in Seething Lane contains a number of paving stones representing his life and events that occurred during it. You can read more about them here and here. Just across the road is St Olave Hart Street. It’s tiny and wonderfully atmospheric, being one of the few surviving Medieval buildings in London.

Incidentally, it was exactly 67 years ago today that the terrible Smithfield Market fire of 1958 broke out. I have written about it in my recent blog Goodbye Smithfield Market – Special Edition.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …