For the first half of the 18th century the river remained London’s main thoroughfare. The watermen’s cry of ‘Oars! Oars!’ as they looked for customers constantly rang out in riverside streets. One Frenchman, who hadn’t quite mastered the language but had heard of London’s immoral reputation, thought this an invitation to try a quite different service.

But things were about to change.

By the mid-1750s the bridge was clearly failing in its purpose to provide an adequate river crossing, but the building of a new bridge nearby was constantly blocked by the strong waterman lobby and riverside businesses. Bridge residents showed their objection to a nearby temporary wooden bridge by persistently trying to burn it down.

But something had to be done, the bridge being …

Narrow, darksome, and dangerous … from the multitude of carriages … with frequent arches of strong timber crossing the street from the tops of houses to keep them together and stop them falling into the river.

Thomas Pennant writing in 1750.

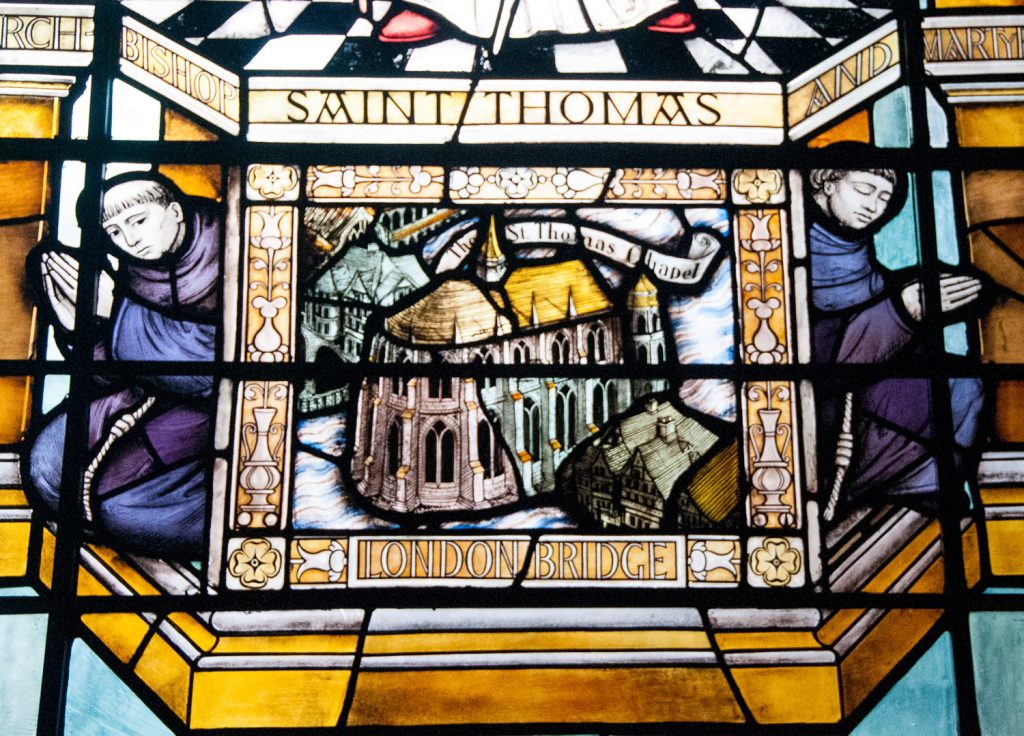

A compromise was reached in 1757 by pulling down all the houses on the bridge as well as the chapel of St Thomas the Martyr. The bones of the cleric who oversaw the earliest building of the bridge in the 12th century, Peter de Colechurch, were interred there and some accounts say that, when they were uncovered, the workmen unceremoniously tossed them into the Thames.

St Thomas’s chapel is commemorated with a stained glass window in St Magnus-the -Martyr church. I like the sleepy monk on the right …

But the bridge continued to be congested and, for a growing port, increasingly seen as an obstacle to trade. The momentum for change was unstoppable and the old bridge was doomed …

Few tears were shed over its destruction. As Bernard Ash writes in his fascinating book The Golden City : ‘This was not a sentimental generation. It looked forward not backward. It saw no picturesqueness in the narrow, inconvenient ways of its forebears or in the narrow, inconvenient and often makeshift things they had built’.

But the river was no longer the highway of London – private carriages and hackney coaches were taking over. As Ash eloquently points out, all the watermen’s traffic had ‘run away on wheels’.

A new bridge designed by the Scottish engineer John Rennie (1761-1821) was decided upon. The work went ahead in 1824 under the supervision of his sons, John Rennie the Younger and George. In order to keep the old bridge open for traffic during construction it was decided that the new one should be on a different alignment, about one hundred feet upstream.

Construction took seven and a half years at a cost of two and a half million pounds and the lives of forty workmen, many perishing in the fast flowing water caused by the continued existence of the old bridge.

The opening (depicted below) was described in The Times as …

the most splendid spectacle that has been witnessed on the Thames for many years.

The King arrived at about 4pm and the red carpeted stairs where he landed can be seen leading up to the bridge on the far side of the river. A huge pavilion where a sumptuous banquet was held had been erected on the bridge. The royal standard can be seen flying from the pavilion at the north end. The King was accompanied by his wife Adelaide – hence the name of the 1925 Art Deco office block on the north east side of the bridge that you can see today.

Here’s a view of Adelaide House from the Thames path …

London’s growing prosperity led to increased traffic and more congestion problems for the bridge …

By 1896 the bridge was the busiest point in London, and one of its most congested – on average 8,000 pedestrians and 900 vehicles crossed every hour. Subsequent surveys showed that the bridge was sinking an inch every eight years, and by 1924 the east side had sunk some three to four inches lower than the west side. Clearly the bridge would eventually have to be removed and replaced.

In 1967, to many people’s astonishment, Rennie’s bridge was put up for sale and, to more astonishment, was bought on 18th April 1968 by the Missourian entrepreneur and oilman Robert P McCulloch for $2,460,000. Under no illusion that he had bought Tower Bridge (as some papers mischievously reported) he moved it piece by piece to Lake Havasu City Arizona – all 10,276 granite blocks individually numbered.

I think it looks great …

You can read more about Lake Havasu here along with the 50th anniversary last year of the bridge’s purchase.

The London Bridge we see today was constructed between 1967 and 1972 and opened by Queen Elizabeth on 17th March 1973. I like this nighttime picture …

Now there are security blocks in place as a result of the terrorist attack in June 2017…

I hope you have enjoyed these short histories of the bridges that have been known as ‘London Bridge’. Incidentally, if you do a Google search for ‘London Bridge images’ you will see that, on most American sites, you’ll be shown pictures of Tower Bridge!