Having been away I have neglected the blog somewhat so I hope you will forgive me if this week’s offering is a rather miscellaneous collection of City images and a few pics from my holiday by Lake Como!

HMS Belfast and Tower Bridge look good on a grey, cloudy day …

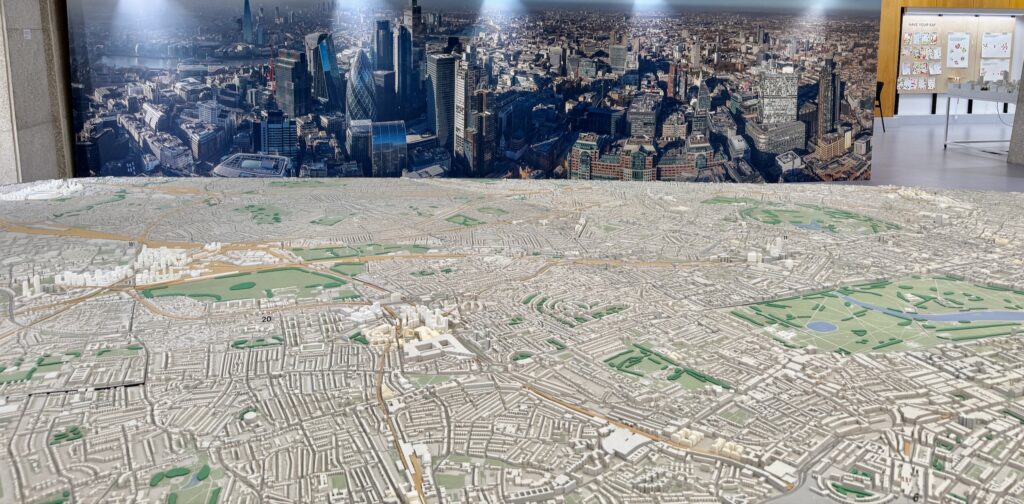

The City skyline from nearby …

The poor Gherkin is gradually being surrounded and the Walkie Talkie really is a monster from this viewpoint …

Control of protected views has still managed to give St Paul’s the priority it deserves. Long may this continue as even more development gains approval …

The Shard from Hay’s Galleria …

The refurbished facade of the old headquarters of the Eastern Telegraph Company on Moorgate is gradually being revealed including this fabulous stained glass …

At first it was called Electra House (named after the goddess of electricity) and the centre section shows her perched on top of the world. You can read more about her and the building in my April 2020 blog.

Nice brickwork in St Thomas Street on the south side of London Bridge Station …

A wacky installation at Vinegar Yard across the road …

Re-purposed warehouses nearby …

A re-purposed pub across the road from St Bartholomew the Great …

Angel III by Emily Young (2003), Paternoster Square, opposite St Paul’s Cathedral …

You can read my blog about City Angels (and Devils!) here.

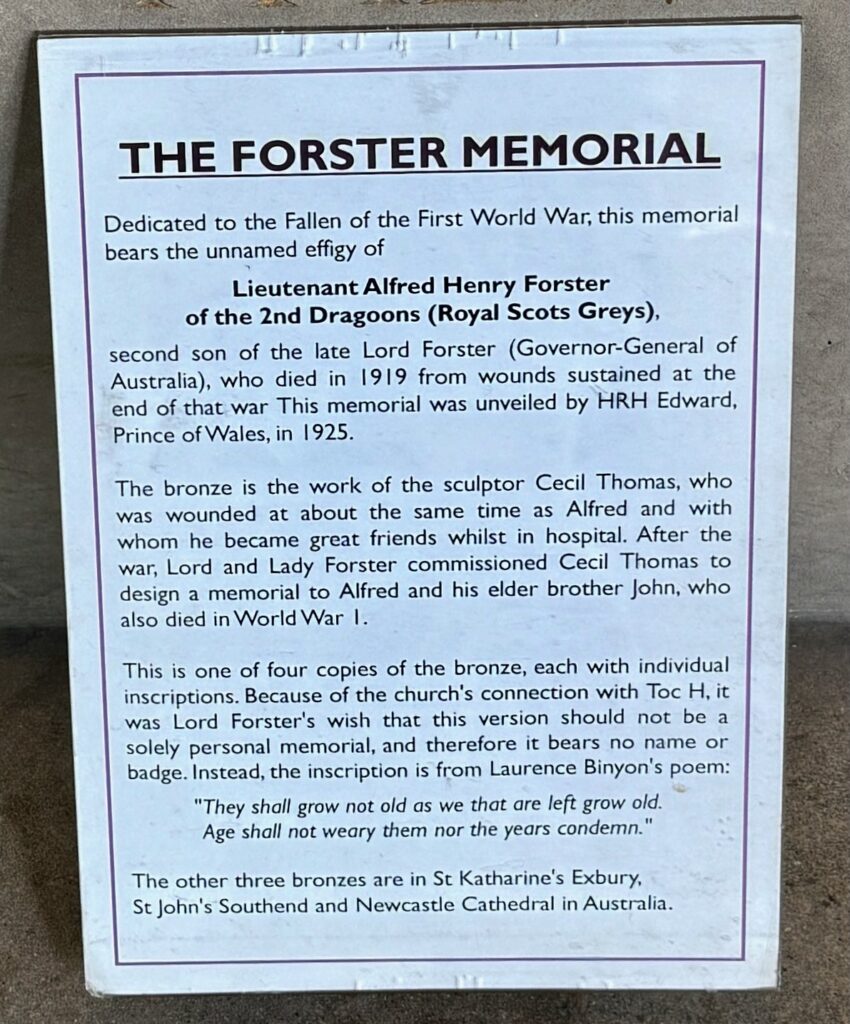

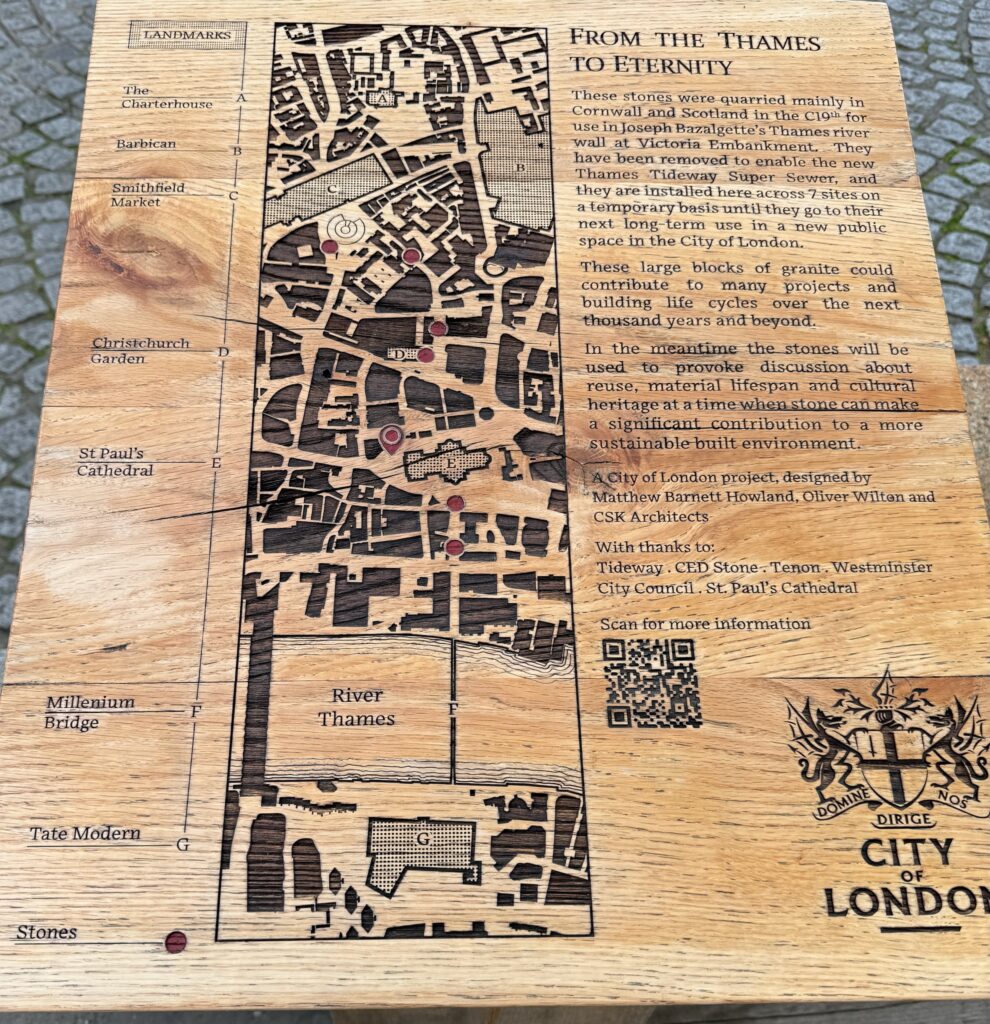

Also outside the Cathedral …

The explanation …

Golden cherubs at Ludgate Circus …

This building was originally the London headquarters of the Thomas Cook travel agency. Built in 1865, the first floor was a temperance hotel in accordance with Cook’s beliefs. Read more about the cherubs, and many of their fellows, in my Blog Charming Cherubs.

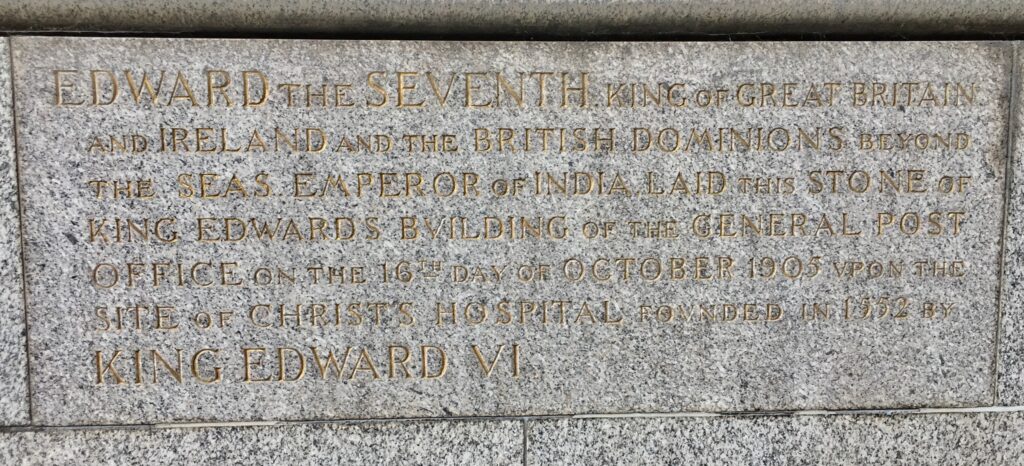

The wording on this foundation stone in King Edward Street emanates pride in the British Empire at its height …

Across the road nearby are the coat of arms and the motto of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. It’s the Newgate Street Clock, the Worshipful Company’s 375th anniversary gift to the City of London …

The motto Tempus Rerum Imperator can be translated as Time, the Ruler of All Things.

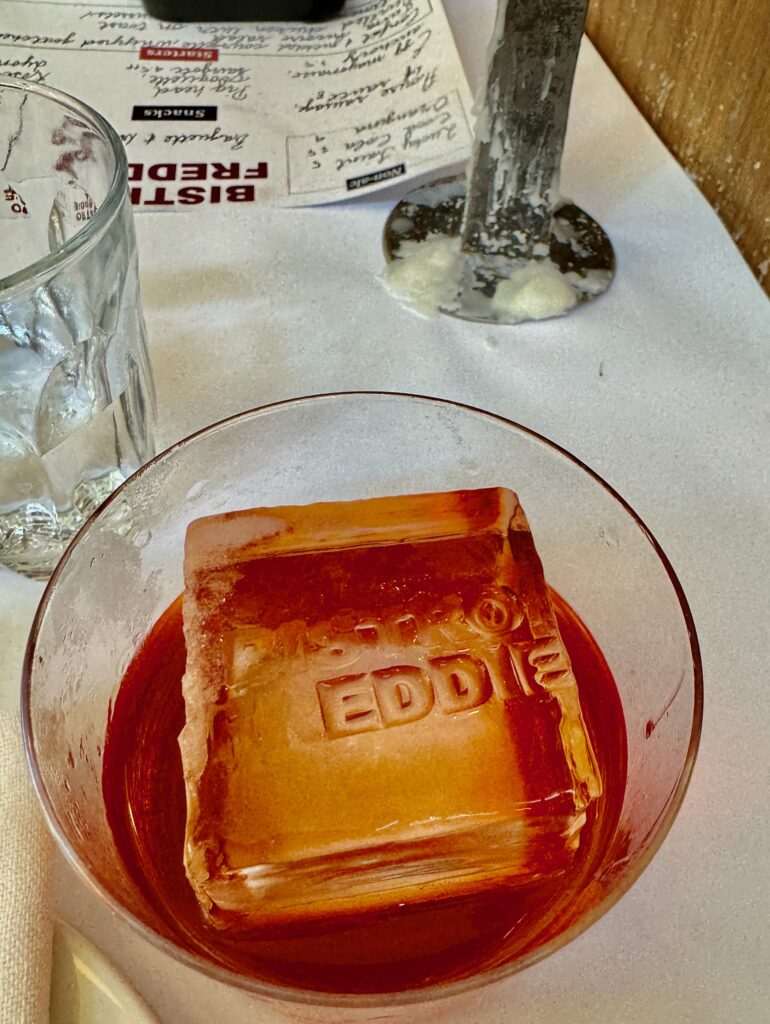

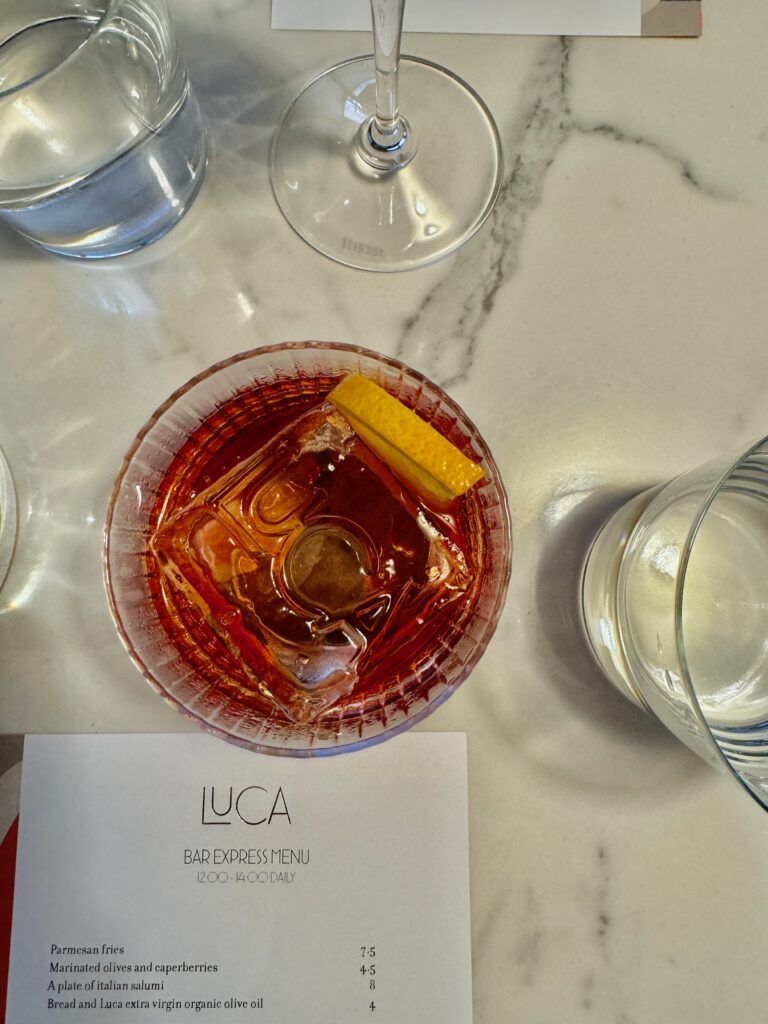

On a lighthearted note – food and drink.

Branded ice in my Negroni at Bistro Freddie …

And another, not quite so obvious, at Luca …

Pudding at the Bleeding Heart Bistro …

Watching the calories whilst on holiday …

We visited lovely Lake Como for ten days.

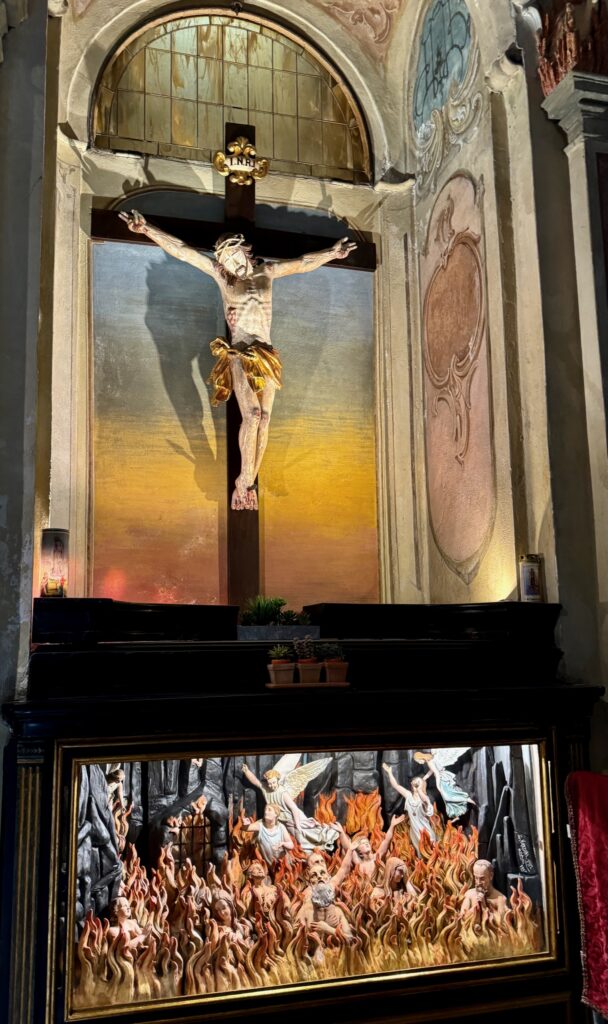

The stunning Cathedral …

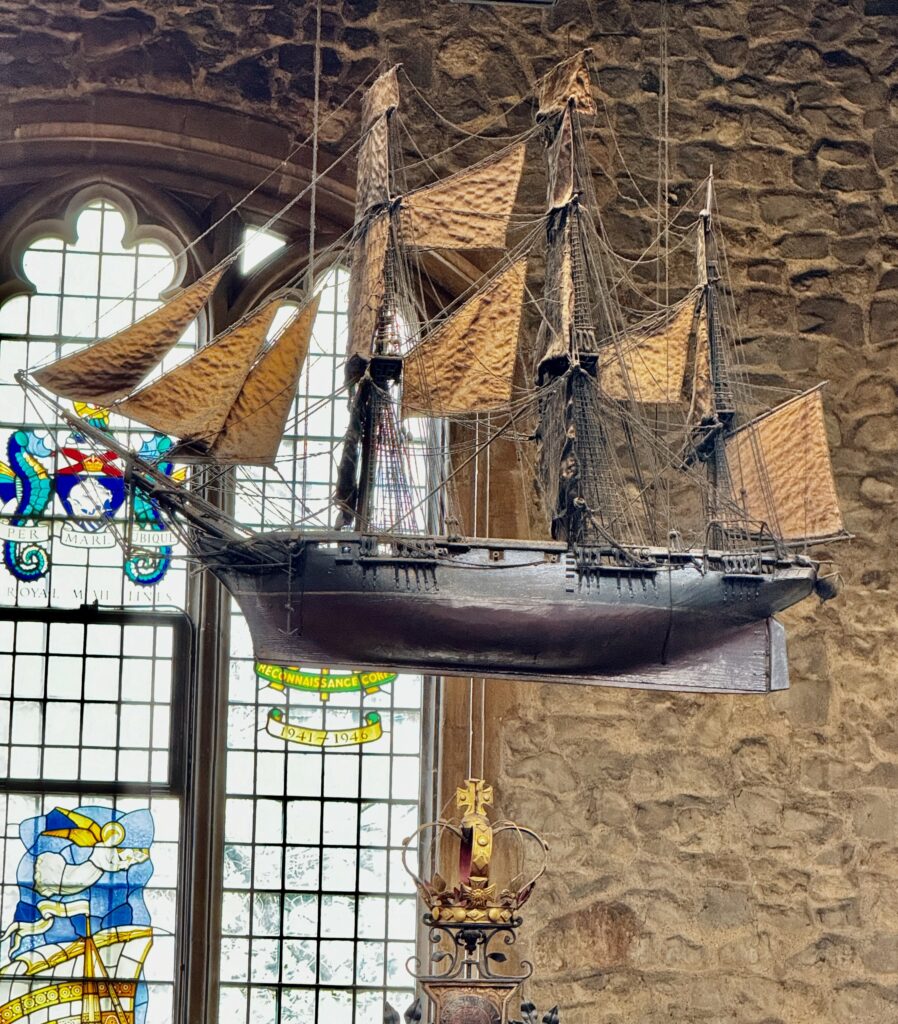

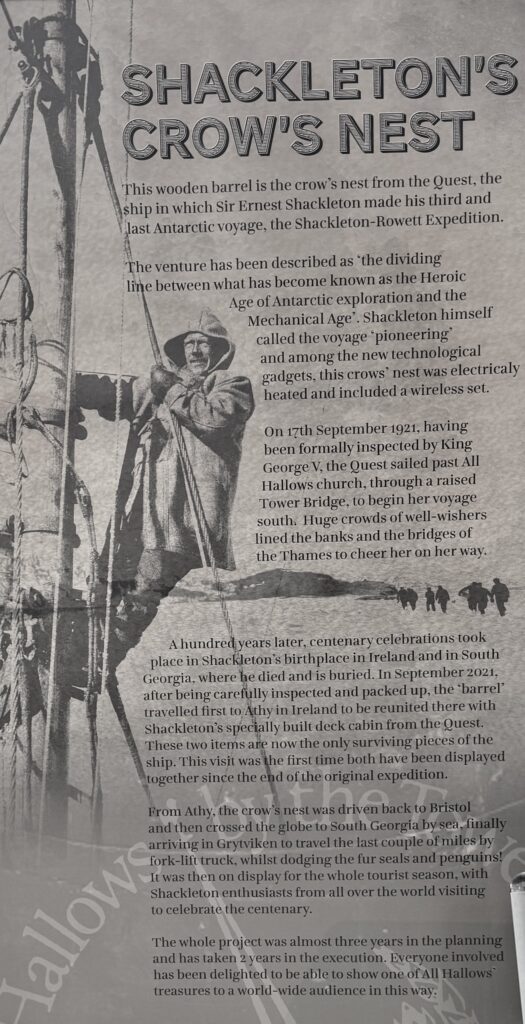

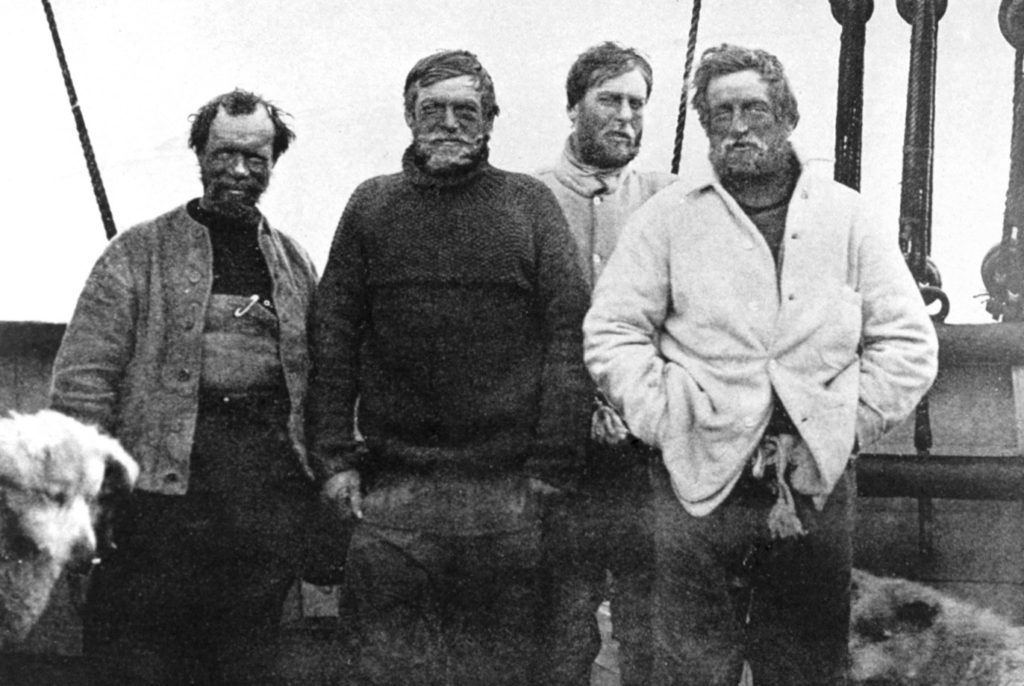

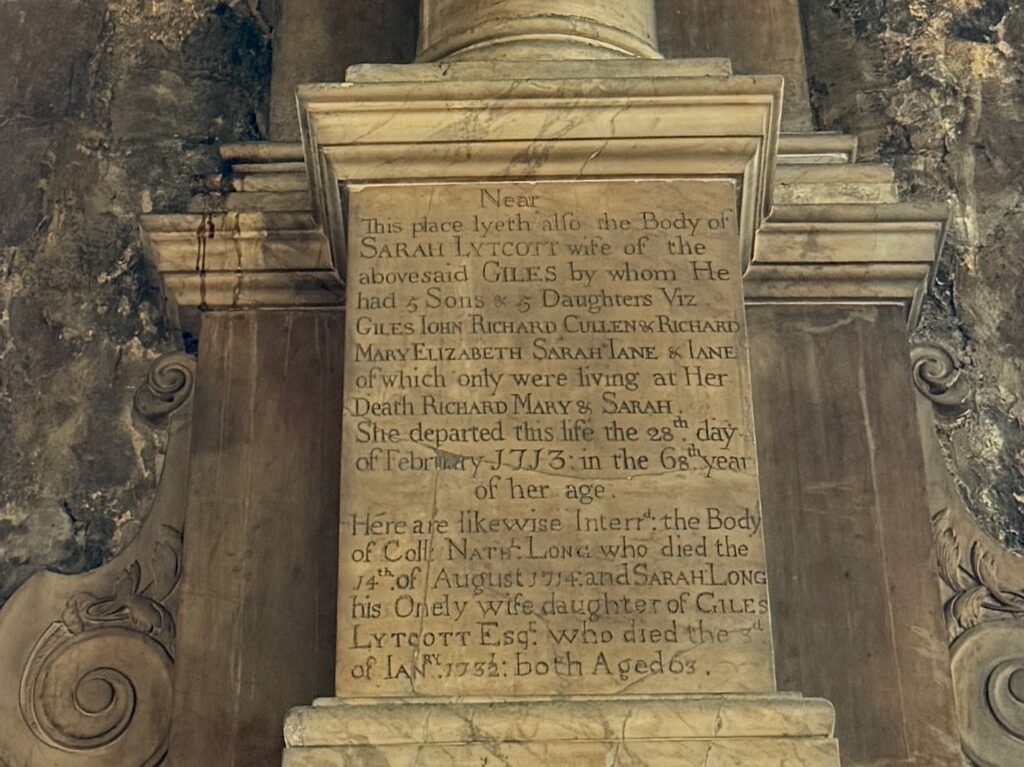

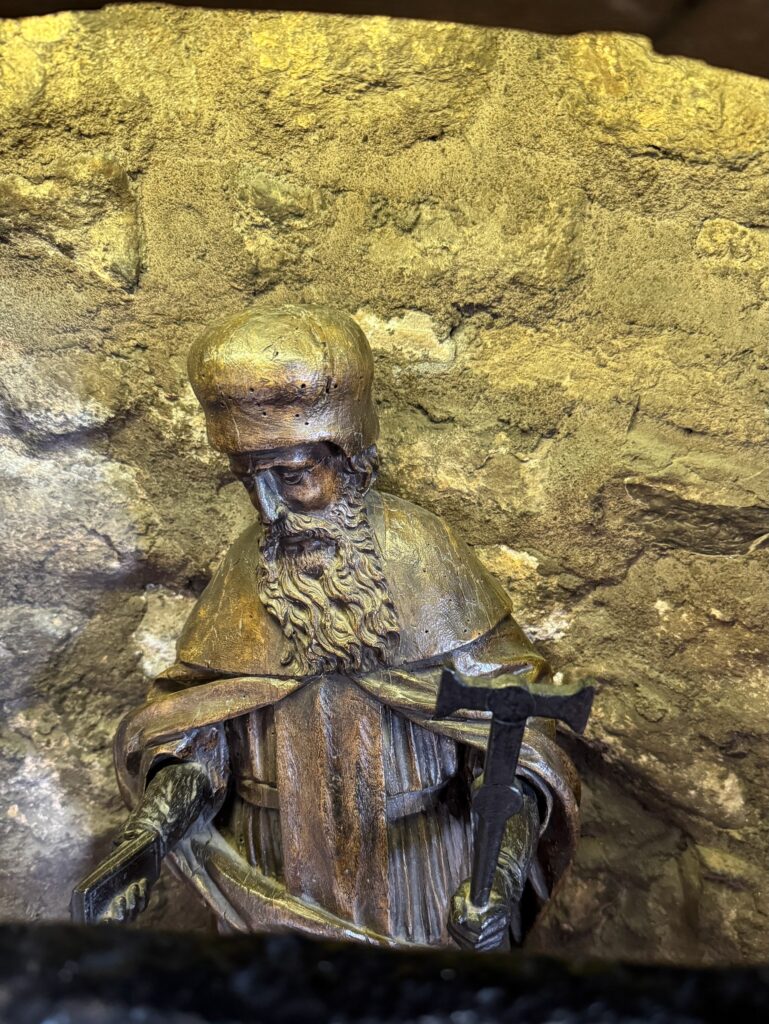

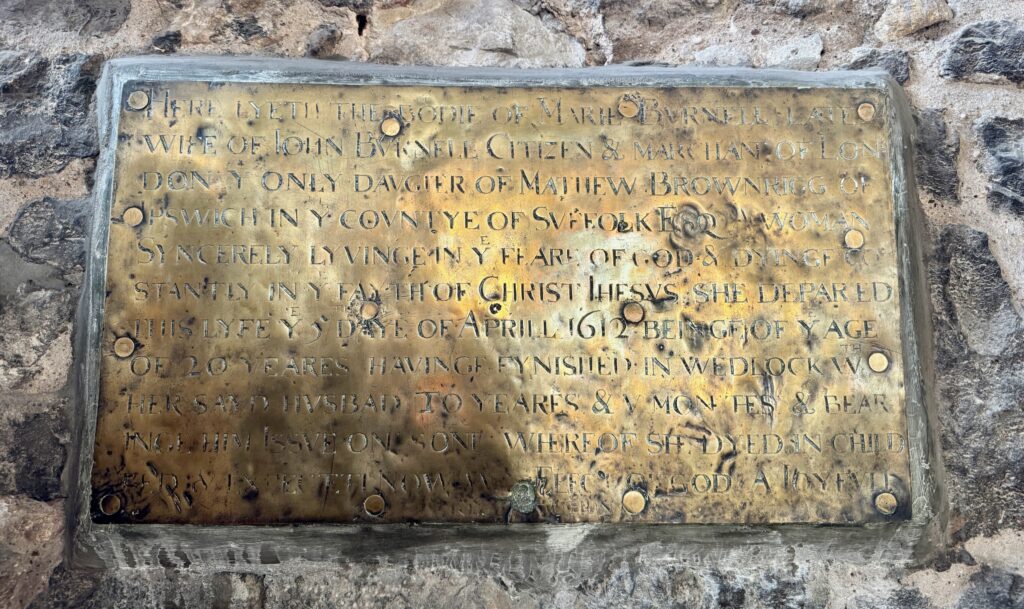

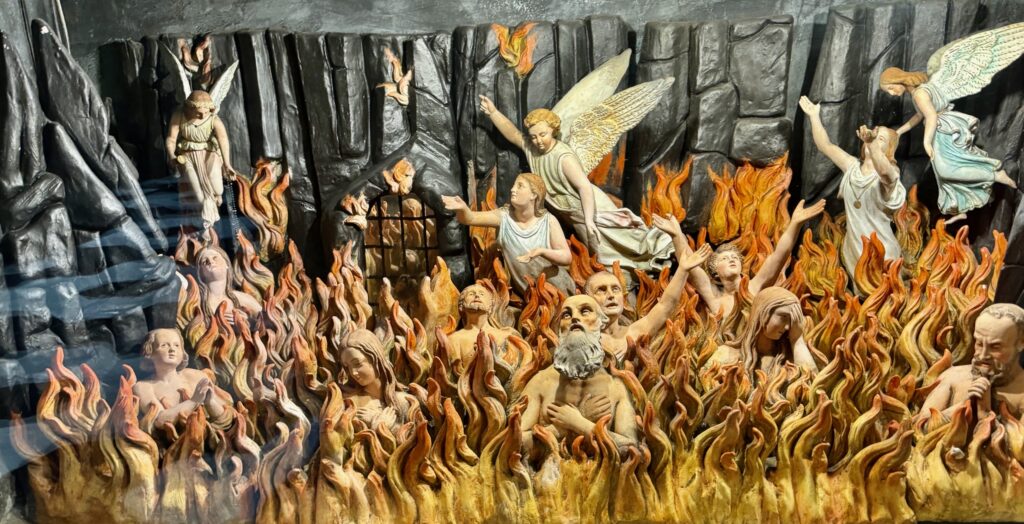

In a nearby church …

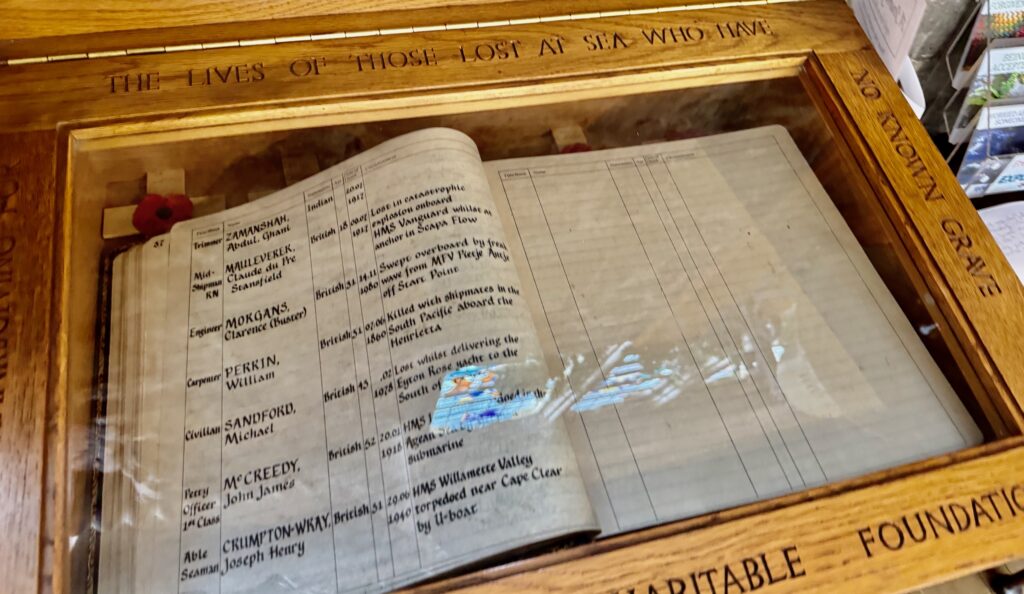

Lost souls ..

Some fascinating outdoor sculpture …

The extraordinary two above are by Fabio Viale.

This one is by Daniel Libeskind …

I know what the box on the left is for but I’m not sure about the one on the right …

Shopping opportunities …

Como silk is very, very beautiful …

Finally, some classy tourist stuff to take home as a memento …

Back home to London in the evening – nice to see a duck on night patrol …

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …