Postman’s Park was once the churchyard to the adjacent church, St Botolph Aldersgate, but between 1858 and 1860 it was cleared of human remains and re-landscaped as a public space. A number of gravestones remain and you can see some of them now stacked neatly against the northern churchyard wall …

Nearby, in 1829, the General Post Office had moved in to a vast new building on St Martin Le Grand and, when the new park opened, it quickly became a popular leisure area for the post office workers and, as a result, the park soon became known as Postman’s Park (EC1A 7BT).

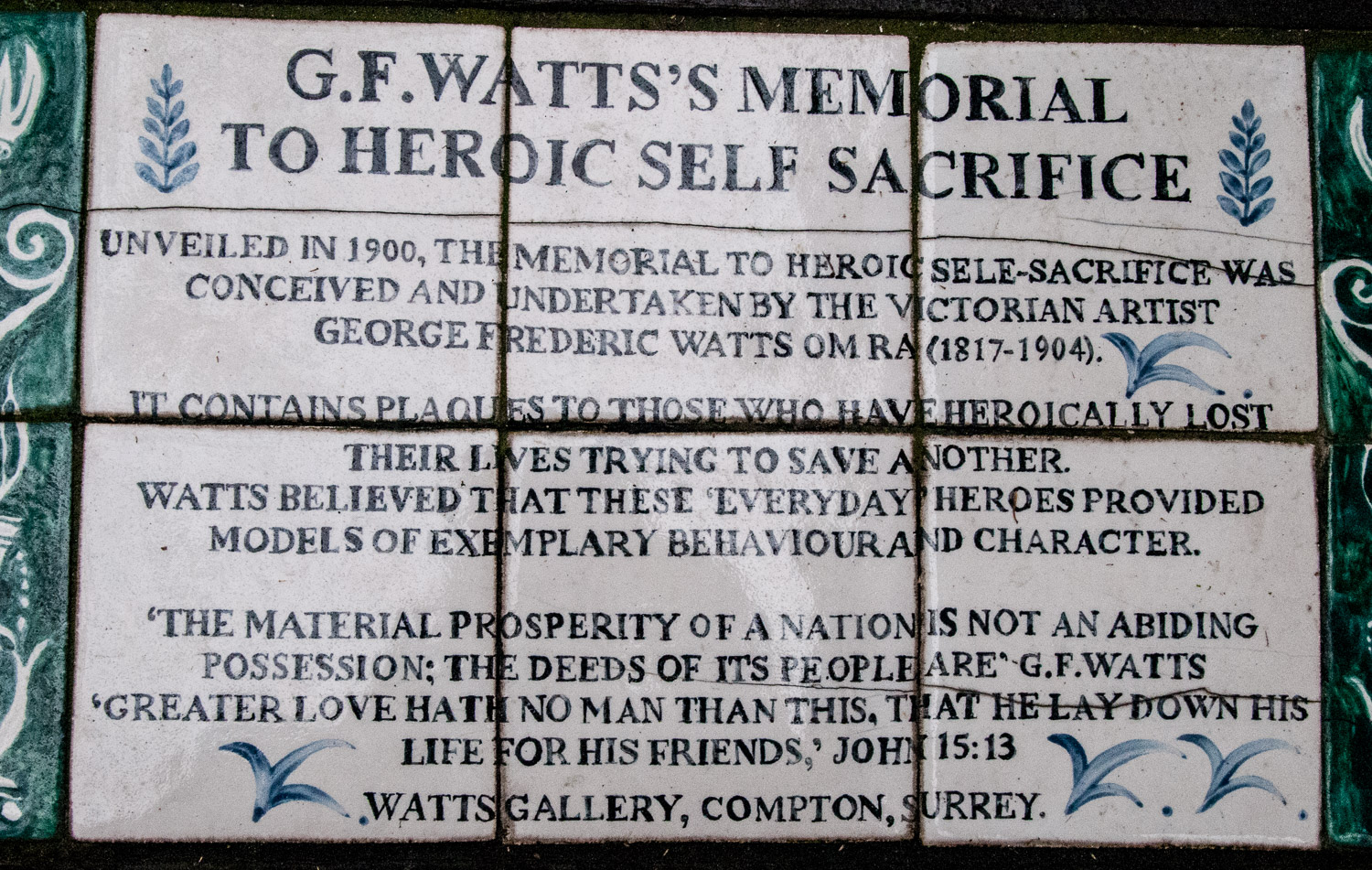

It contains now what is, in my view, one of the most interesting, poignant and rather melancholy memorials in the City – The G F Watts Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice. This plaque nearby contains a useful mini-history …

In the late 1890s the idea was mooted that the park would be an ideal location for a memorial to ‘ordinary’ and ‘humble’ folk who had lost their lives endeavouring to save the lives of others. Two of its most enthusiastic supporters were the artists George Frederic Watts (1817 – 1904) and his wife Mary (1849 – 1938). There are some nice images of both him and his wife on the National Portrait Gallery website. Here he is and here his wife Mary.

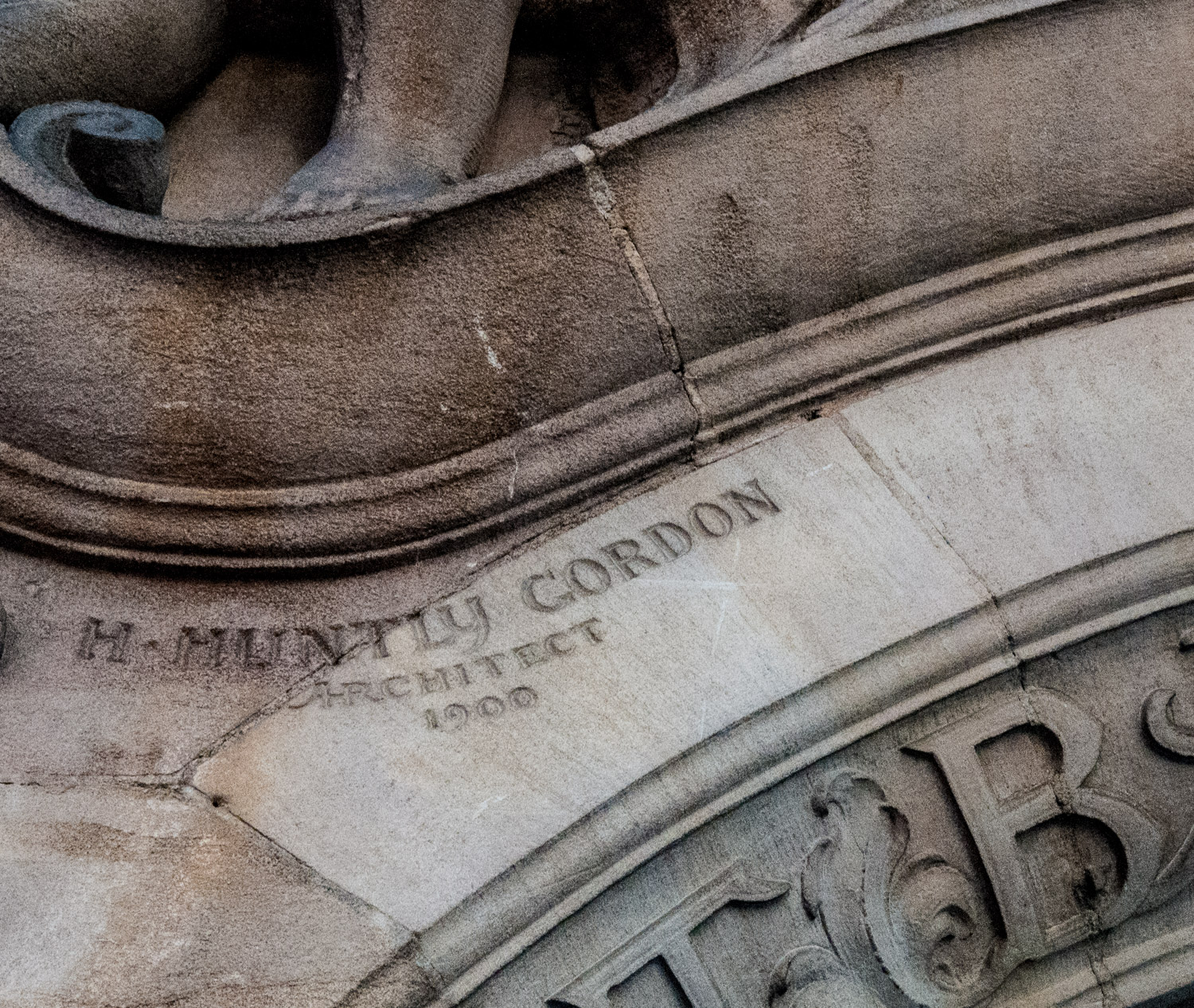

After much debate about its positioning and design, the memorial was finally declared finished and open on 30 July 1900, the building looking very much as it does today …

The memorial consists of 54 ceramic tablets which were gradually added over the years, each describing a particular act of selfless heroism. I have chosen to write about four of them using as my source the splendid book by the historian John Price: Heroes of Postman’s Park (ISBN 9780750956437). You can also, like me, become a Friend of the Watts Memorial, and more details can be found here.

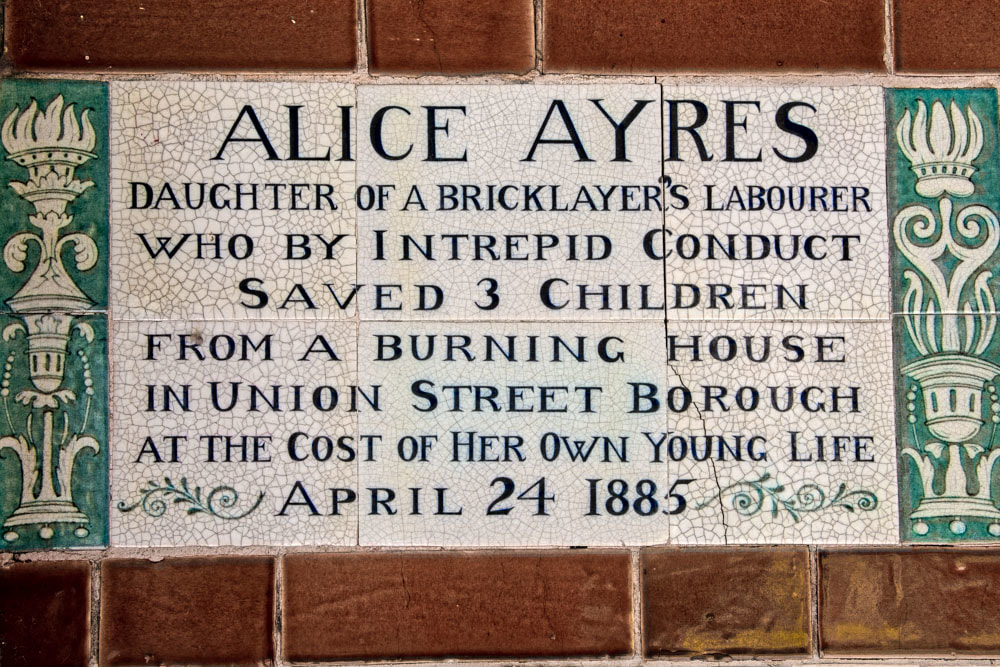

The first of my four heroes is Alice Ayres …

The picture above shows Alice Ayres as portrayed by the Illustrated London News in 1885 (Copyright the British Library Board). Her commemorative plaque reads as follows and was the first to be installed …

It was Alice’s brave act that prompted Watts to write to the Times newspaper and suggest the creation of a memorial

That would celebrate the sacrifices made by ‘likely to be forgotten heroes’ by collecting ‘…a complete record of the stories of heroism in every-day life’.

Alice threw down a mattress from a burning building and successfully used it to rescue three children …

From The Illustrated Police News 2nd May 1885 Copyright, The British Library Board.

Alice eventually jumped herself but received terrible injuries and died two days later. Incidentally, if her name rings a bell with you it could be because, in the 2004 film Closer, one of the characters, Jane Jones, sees Alice’s memorial and decides to adopt her name.

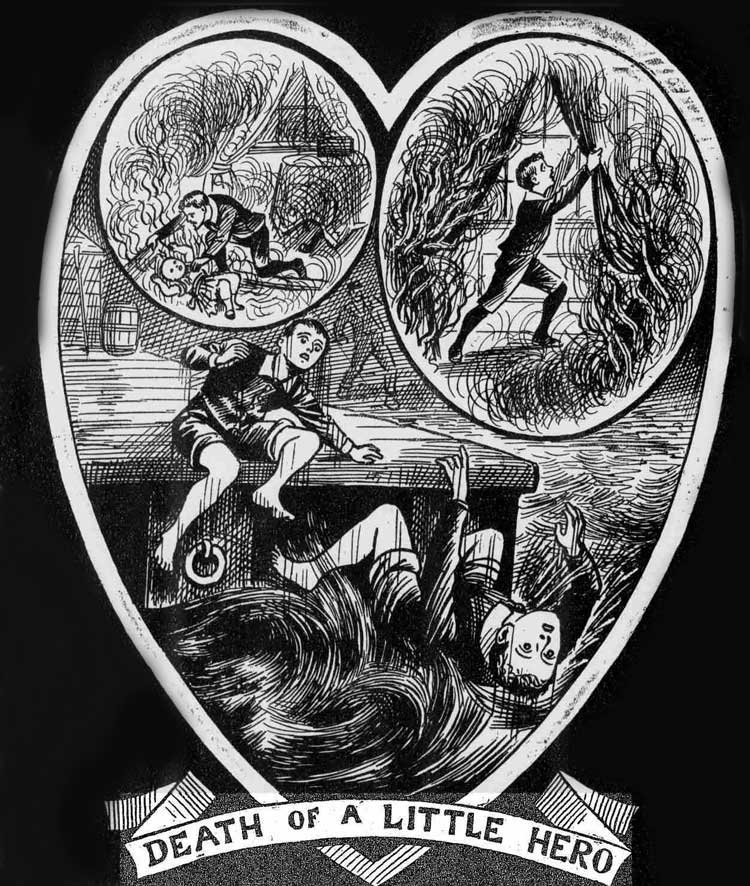

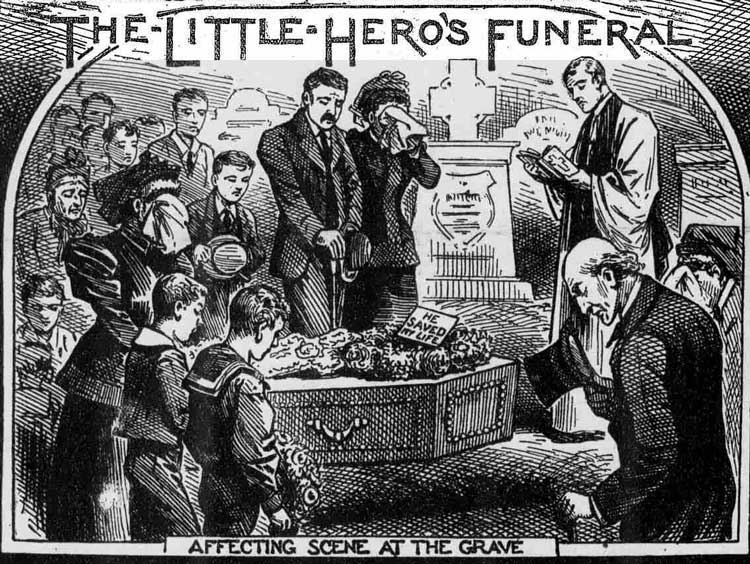

John Clinton was only 10 when he dived into the Thames to save another little boy’s life. Unfortunately, after the rescue, John himself slipped back into the water and drowned. According to his father this wasn’t his first brave act, having saved a baby from a fire and tearing down burning curtains that were threatening the house. Both acts were commemorated in this illustration …

From The Illustrated Police News, 28th July 1894. Copyright, The British Library Board.

His funeral was widely reported …

I am indebted to the editor of the London Walking Tours website for this photograph of John Clinton’s image on his tombstone in Manor Park cemetery …

His Postman’s Park plaque …

And now another brave lady,

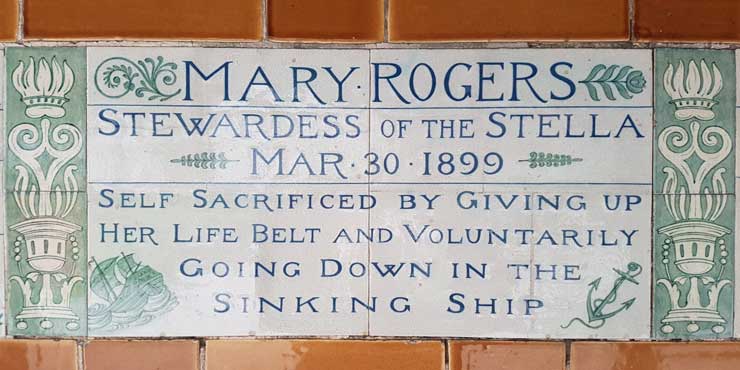

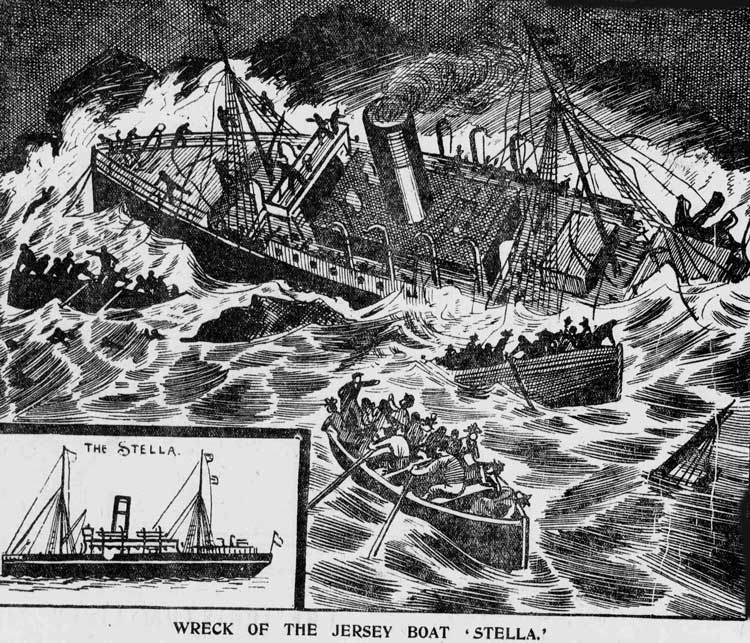

Many of these memorials give us glimpses of the nature of society at the time these events took place, and Mary’s story is a typical example. It is most unlikely that she would ever have found herself serving at sea had it not been for the fact that her husband, Richard, was drowned when the cross channel steamer SS Honfleur sank in the English Channel on 21 October 1880.

The steamer was operated by the London & South Western Railway Company (LSWR) and so Richard was one of their employees. It was common practice at the time for railway companies to offer employment to the widows or children of deceased employees so as to avoid having to pay compensation or provide a pension. Almost immediately after the birth of her son in January 1881, Mary began work as a stewardess for LSWR. Her earnings were 15 shillings a week plus any tips received from passengers. For a woman in her circumstances, this was a decent, stable income and in modern terms, a job with prospects. It also kept her family out of the workhouse.

Mary Rogers – 1855-1899

The story of the sinking of the SS Stella is a gripping one and rather too complicated to relate in detail here. If you want all the details either get hold of a copy of John Price’s book and/or have a look at this website run by Jake Simpkin, a Blue Badge holder and south of England historian.

From The Illustrated Police News – 8th April 1899. Copyright, The British Library Board

The Times reported that Rogers …

Helped ‘her ladies’ from the cabin into the lifeboats. Next she gave up her own lifejacket, and then when urged to get into the lifeboat refused for fear of capsizing it. She was told it was her only chance, but she persisted that she could not save her own life at the cost of a fellow creature’s. She waved the lifeboat ‘farewell’ and bid the survivors to be of ‘good cheer’.

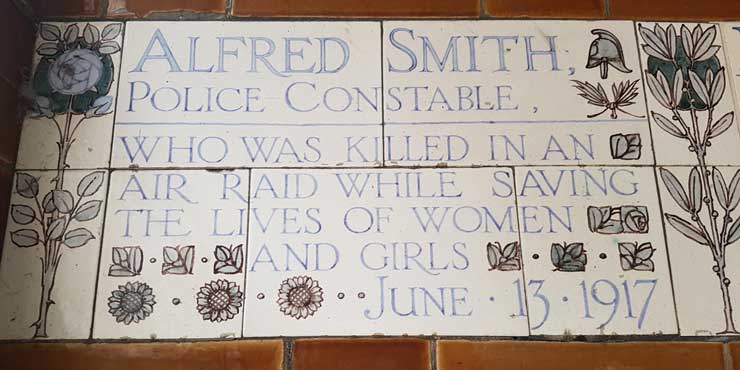

Walking down Central Street one day I noticed this green plaque on the other side of the road …

On crossing over to take a look this is what I saw …

I took a picture, resolving to do further research and then discovered that the brave Alfred Smith is commemorated on the Watts Memorial …

PC Smith, 37 years old, was on duty in Central Street when the noise was heard of an approaching group of fourteen German bombers. One press report reads as follows …

In the case of PC Alfred Smith, a popular member of the Metropolitan Force, who leaves a widow and three children, the deceased was on point duty near a warehouse. When the bombs began to fall the girls from the warehouse ran down into the street. Smith got them back, and stood in the porch to prevent them returning. In doing his duty he thus sacrificed his own life.

Smith had no visible injuries but had been killed by the blast from the bombs dropped nearby. He was one of 162 people killed that day in one of the deadliest raids of the war.

His widow was treated much more kindly than Mary Rogers. She received automatically a police pension (£88 1s per annum, with an additional allowance of £6 12s per annum for her son) but also had her MP, Allen Baker, working on her behalf. He approached the directors of Debenhams (whose staff PC Smith had saved) and solicited from them a donation of £100 guineas (£105). A further fund, chaired by Baker, raised almost £472 and some of this was used to pay for the Watts Memorial tablet, which was officially unveiled on the second anniversary of Alfred’s death.

Watts used newspaper reports to decide who should receive the honour of a plaque, but in one case the report was false and the ‘hero’ didn’t exist. Unfortunately, Watts didn’t see the newspaper article correcting the mistake and the plaque went up anyway. If you want to know the identity of the non-existent ‘hero’ I am not going to reveal it here, and you will have to buy John Price’s book to find out.

I wrote about some more of the heroes from the memorial in an earlier blog which you can access here.