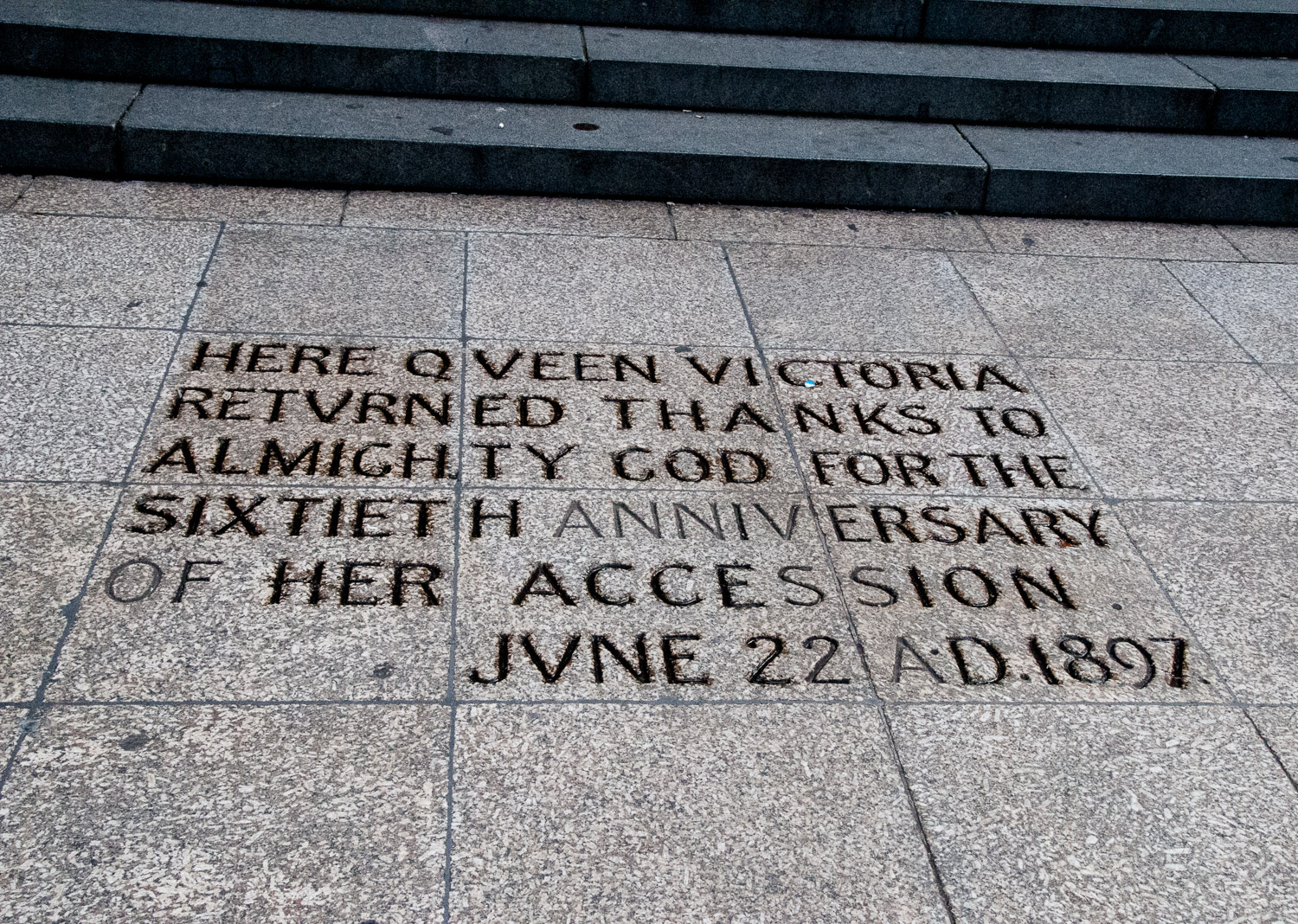

What happened to Temple Bar in the 126 years between when it was demolished in 1878 and its return to the City in 2004?

It once marked the boundary between the City of London and the City of Westminster and now stands proudly at the entrance to the Paternoster Square piazza, alongside St Paul’s Cathedral. It has been nicely spruced up having been relocated from an exile in the countryside, the second move in its history since it was originally erected in Fleet Street in 1672.

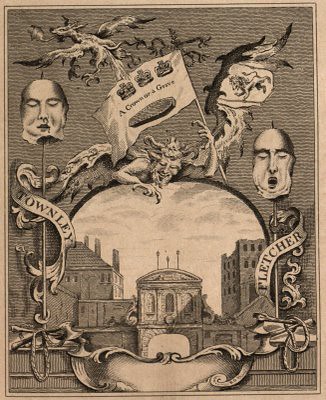

The City of London once had seven gates which restricted access and could be closed, or barred, for security or in times of emergency, but only Temple Bar survived into the nineteenth century. It escaped demolition for a number of reasons, including its design being attributed to Sir Christopher Wren and the fact that it was the point at which royal personages were welcomed into the City by the Lord Mayor. It also had the macabre reputation of being the place where the heads and other body parts of executed traitors were displayed before the public. The last two to meet this fate were Francis Townley and George Fletcher who were executed for their part in the 1745 rebellion which aimed to place Bonnie Prince Charlie on the throne.

A contemporary print showing the traitors’ fate – ‘A Crown or a Grave’ was the Rebellion’s motto

The heads of Fletcher and Townley were put on the Bar August 12, 1746. On August 15th Horace Walpole, writing to a friend, says he had just been roaming in the City, and

passed under the new heads on Temple Bar, where people make a trade of letting spy-glasses at a halfpenny a look

A storm in March 1772 finally blew the grisly things off into the street and ‘against the sky no more relics remained of a barbarous and unchristian revenge’.

The room above the street was once used for the more mundane purpose of storing the ledgers of the nearby Child’s bank.

By the 1860s the Bar had become a serious obstruction to traffic, the road needed widening and also room was required for the construction of the Royal Courts of Justice. Demolition was decided upon but fondness for the Bar resulted in it being taken down ‘brick by brick, beam by beam, numbered stone by stone’, and stored in a yard off Farringdon Road until a decision for its re-erection could be reached.

Demolition, above, started on January 2 1878 and was completed just eleven days later. It was replaced by the Temple Bar Memorial and on this monument today is a plaque commemorating the removal of the old Bar – a curtain is being dramatically drawn over it.

Farewell Temple Bar – the Angels of Fortune and Time pull across the curtain

Ten years later, enter Lady Valerie Meux, a beautiful ex-actress and singer who had married Sir Henry Meux of the wealthy brewing family. Sir Henry’s family never accepted her and, I must say, she was a tad eccentric, driving herself around London in a phaeton carriage drawn by a pair of zebras. She took a fancy to Temple Bar and in 1887, her husband having purchased it from the Corporation of London, all 400 tons of it were transported to their house in Theobalds, Hertfordshire.

The historian E V Lucas, who had walked through the arch as a child, was outraged and later wrote in his book A Wanderer in London …

The transplantation of the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon to the British Museum – from dominating the Acropolis and Athens to serving as a source of complexity to Londoners in an overheated gallery in Bloomsbury – is hardly more violent than the transplantation of Temple Bar from Fleet Street and the City’s feet to Hertfordshire and solitude

Lady Meux was delighted with her purchase. At Theobalds it was meticulously reconstructed as a new gateway to the estate and, in the upper chamber, she entertained guests such as Winston Churchill and the Prince of Wales. I love this picture of Lady Meux serenading her husband with her banjo whilst he leans against her chair wearing his tweeds and stout walking boots.

Here she is, more formally, in an 1881 painting by James McNeill Whistler entitled Harmony in Pink and Grey (Frick Collection).

Lady Meux died in 1910 and the Bar remained on the estate, sadly suffering from the effects of the weather and some vandalism.

Fast forward to 1976 and the Temple Bar Trust was established with the intention of returning it to London. This was finally achieved on 10 November 2004 when, in its new location, it was opened by the Lord Mayor.

Temple Bar in its new home

The upper room where Lady Meux entertained – the statues are of Charles I and Charles II

All credit to the Trust, the City of London Corporation and the Livery Companies who put together the funding needed to bring the Bar back to the City – I think it looks terrific.

Also, though, spare a thought for the beautiful, wilful and eccentric Valerie Meux. I think she deserves recognition too – who knows what might have happened to this great building were it not for her intervention.