Isn’t it nice when the sun is out! I decided it was time for another wander around the City and from the Barbican Highwalk I spotted an old friend who it seems has at last found a permanent resting place …

The Minotaur was made by Michael Ayrton. The creature in the sculpture has been described as ‘looking powerful and muscular. It stands hunched over when on his plinth, but he looks ready to take off running at any moment. It has the body of a man, with heavy muscles in his legs and chest, and two cloven feet. It has the head of a bull with two pointed horns and large, hunched shoulders. Its body is hairy, and its hair moves even though it is made of metal’ …

The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur is one of the most tragic and fascinating myths of the Greek Mythology and you can read more about it here.

Onward to Lombard Street.

I took a walk down the shadowy and rather mysterious Change Alley and came across a building that once housed the Scottish Widows insurance company along with its magnificent crest. At the centre is the mythical winged horse, Pegasus, symbol of immortality and mastery of time. A naked figure, the Greek hero Bellerophon, is shown grasping its mane. In mythology, Bellerophon captured Pegasus and rode him into battle. This explains the motto ‘Take time by the forelock’, or ‘seize the opportunity’. Presumably time could be tamed by taking out a Scottish Widows policy to make provision against the uncertainties of the future …

I next headed down King William Street.

Rising from the flames and just about to take off over the City is the legendary Phoenix bird and from 1915 until 1983 this was the headquarters of the Phoenix Assurance Company (EC4N 7DA). One can see why the Phoenix legend of rebirth and restoration appealed as the name for an insurance company …

Incidentally, have you ever paused to admire the Duke of Wellington statue at Bank junction? And do you think, like I once did, that it was there to celebrate his prowess as a military commander? Well, actually, it’s to commemorate the fact that he helped to get a road built!

It was erected to show the City’s gratitude for Wellington’s help in assisting the passage of the London Bridge Approaches Act 1827 which led to the creation of King William Street. The government donated the metal, which is bronze from captured enemy cannon melted down after the Battle of Waterloo.

A gardener labours diligently at the rear of Brewers’ Hall (EC2V 7HR) …

Philip Ward-Jackson, in his book Public Sculpture of the City of London, tells us of the Trees, Gardens and Open Spaces Committee of the Corporation which was chaired by Frederick Cleary. In his autobiography Cleary recorded that Jonzen’s figure below was intended as a tribute to the efforts of his committee but Ward-Jackson feels that ‘it might have been better described as a symbol of the ‘greening’ of the City in the post-war period’. Most appropriately, Mr Cleary has a garden named after him, and you can read about it in my earlier blog about City gardens generally.

Apparently Jonzen, on being given the subject by the Corporation …

… decided on a kneeling figure of a young man, who, having planted a bulb, was gently stroking over the earth.

There are several other works by Jonzen in the City.

This one, Beyond Tomorrow (1972), is in Basinghall Street, behind the Guildhall …

Sited opposite is this pretty glass fountain by Allen David …

It was commissioned by Mrs Gilbert Edgar, wife of Gilbert H. Edgar CBE, who was a City of London Sheriff between 1963-4. It was unveiled by the Lord Mayor of London on 10th December 1969.

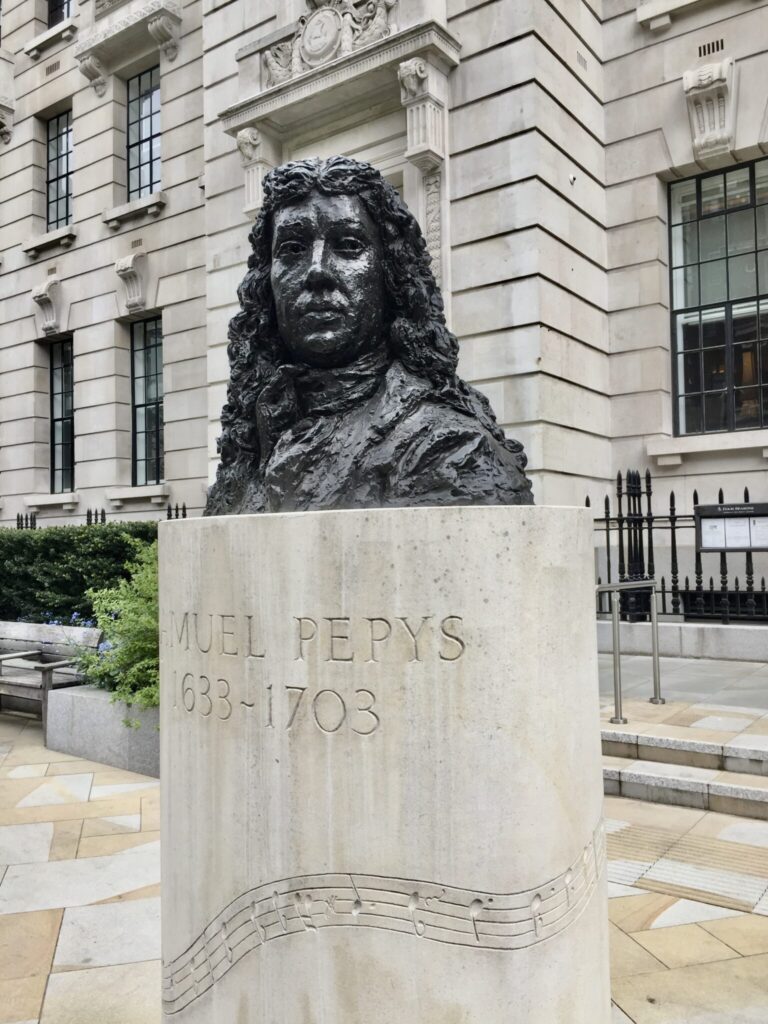

Another work by Jonzen, in the Seething Lane Gardens, is of one of my favourite Londoners, Samuel Pepys. It was commissioned and erected by The Samuel Pepys Club in 1983 …

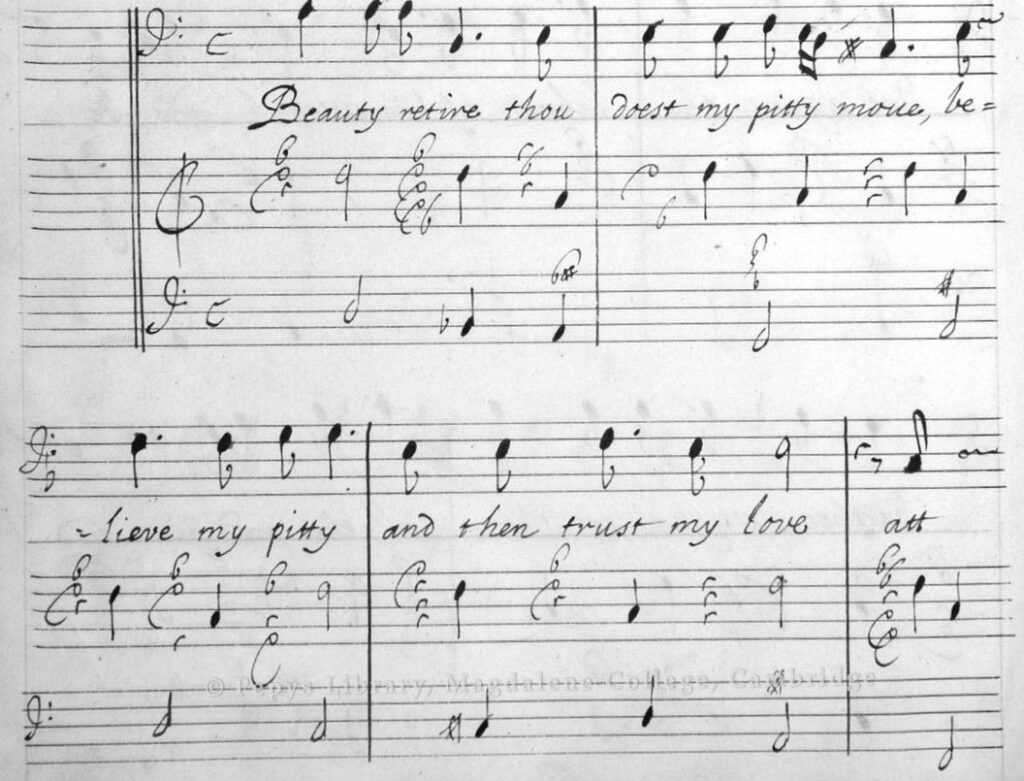

It contains musical notes, so of you can read music you can not only see Sam but also ‘hear’ his voice …

I thought the Guildhall looked nice against the blue sky …

A remarkably wart-free Oliver Cromwell looks fearsome outside the Guildhall Art Gallery with Samuel Pepys and Dick Whittington in the background (EC2V 5AE) …

Dick is on Highgate Hill and has just heard the bells of St Mary-le-Bow ring out ‘Turn again Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London’. He’s giving it some serious thought as his cat curls around his legs (note the tear in his leggings indicating that he has experienced hard times) …

Look closely at the elegant limestone facade of the building and you will see a great collection of bivalves – oyster shells from the Jurassic period when dinosaurs really did walk the earth …

Read more about more of the fossils on view in the City in my blog Jurassic City.

George Peabody was an American financier and philanthropist and is widely regarded as the father of modern philanthropy. Here he sits, looking pretty relaxed, at the northern end of the Royal Exchange Buildings …

Born in Baltimore he became extremely wealthy importing British dried goods and, after visiting frequently, became a permanent London resident in 1838. In retirement he devoted himself to charitable causes setting up a trust, the Peabody Donation Fund, to assist ‘the honest and industrious poor of London’. The Peabody Trustees would use the fund to provide ‘cheap, clean, well-drained and healthful dwellings for the poor’ with the first donation being made in 1862.

Peabody buildings are easily recognised by their attractive honey-coloured brickwork. This block is in Errol Street, Islington …

Immensely respected in later life, he was offered a baronetcy by Queen Victoria but declined it. After his death in 1869 his body rested for a month in Westminster Abbey after which, on the Queen’s orders, his body was returned to America for burial on the British battleship HMS Monarch.

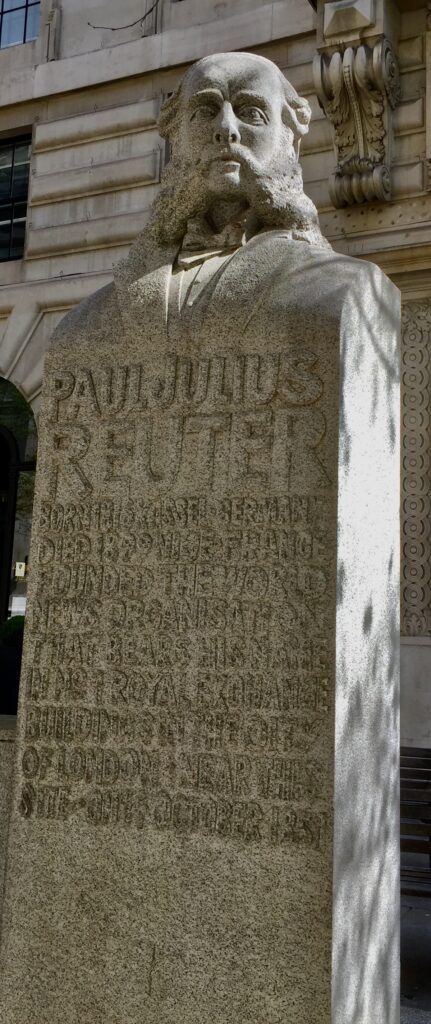

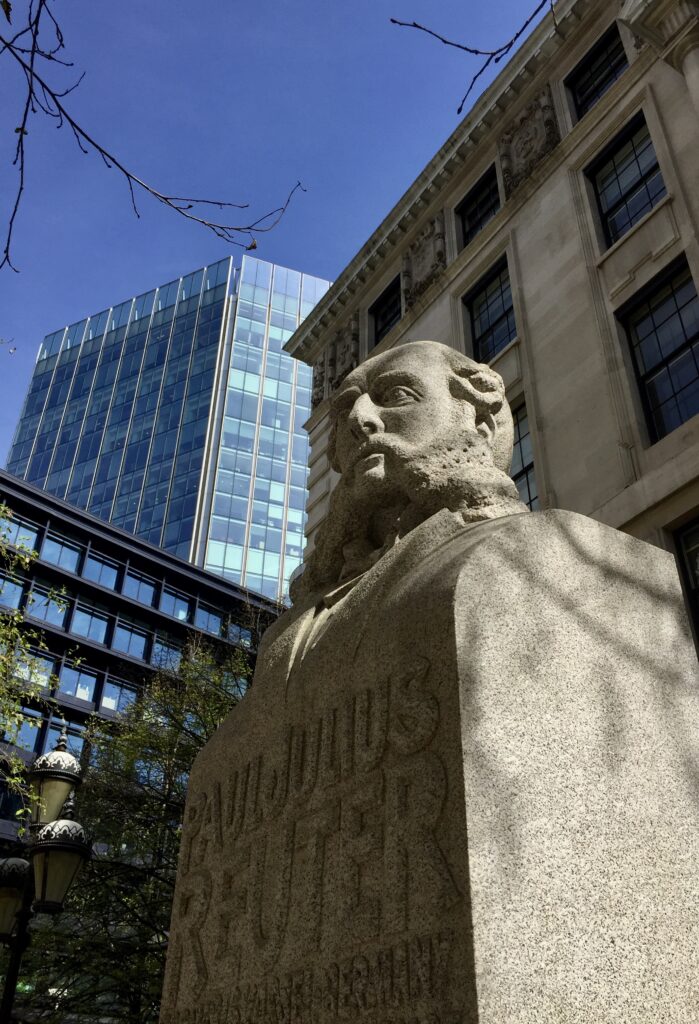

Close to Peabody is a statue to another remarkable man – Paul Julius Reuter. The rough-cut granite sculpture by the Oxford-based sculptor Michael Black commemorates the 19th-century pioneer of communications and news delivery. It is a fitting place for the statue because the stone head faces the Royal Exchange which was the reason why Reuter set up his business in the City. He established his offices in 1851 to the east of the Royal Exchange building. The stone monument was erected by Reuters to mark the 125th anniversary of the Reuters Foundation. It was unveiled by Edmund L de Rothschild on 18 October 1976 …

The life of Reuter was most interesting. Having started his career as a humble clerk in a bank, he went on to ‘see the future’ of transmitting the news – regardless of whether it was financial or world news. If the ‘modern’ technology of telegraphy – also known then as Telegrams – was not in place, Reuter used carrier pigeons and even canisters floating in the sea to convey news as fast as possible. Such was his ambition to be the first with the news.

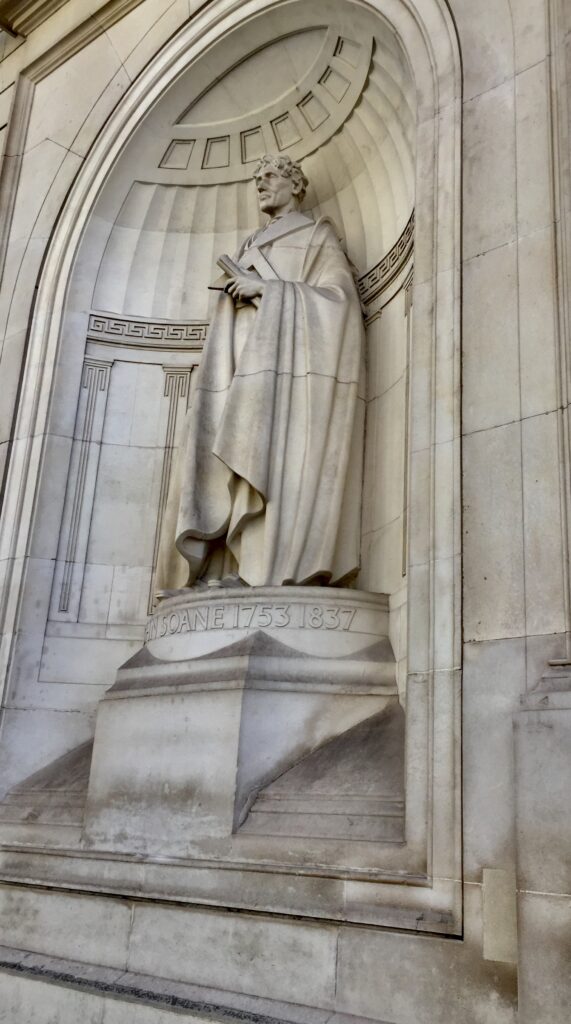

Sir John Soane stands on Lothbury wearing a full-length cloak and holding a bundle of drawings and a set square. The niche is decorated with the neo-Grecian motifs associated with his style. Sir John’s day job was as architect and surveyor to the Bank of England, and he held the position for 45 years. When he resigned in 1833, most of the Bank’s three-acre footprint had been remodelled in some way, and a number of spectacular set-piece facades inserted…

In the wake of the Great War, Britain’s national debt grew to such an extent that Soane’s bank was too small for the business to be transacted; unfortunately, this renovation was done by the architect Herbert Baker in a way that virtually erased Soane’s work.

Many are still angry at the destruction. Here is what the blogger at Ornamental Passions has to say:

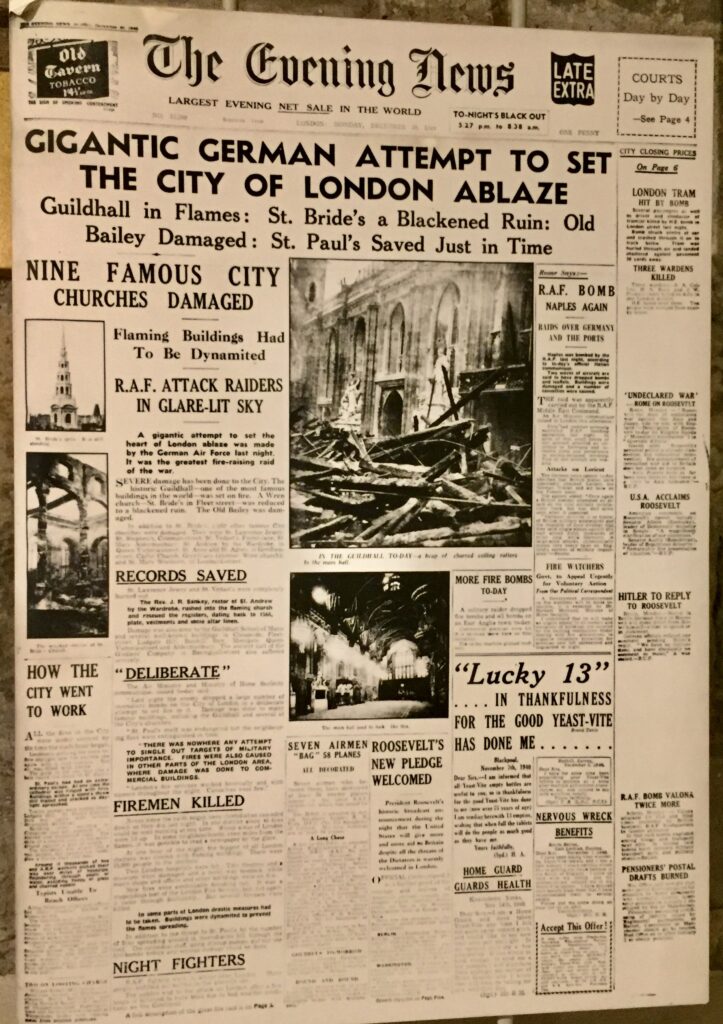

‘The irony of placing a tribute to the architect actually on the sad ruins of his masterpiece was not lost on critics, especially as it is so close to Soane’s much loved Tivoli Corner which Baker had promised to preserve but actually totally rebuilt. He is lucky to have his back turned to an act of vandalism more brutal than anything the Luftwaffe achieved. Indeed, nothing illustrates the Nazi’s abysmal cultural values than that fact that the Bank was untouched in the blitz’. Wow!

Carrying her sword and scales, Lady Justice stands above the Ukrainian flag at the Institute of Chartered Accountants …

Around the corner, the building boasts the poshest letter box in the City …

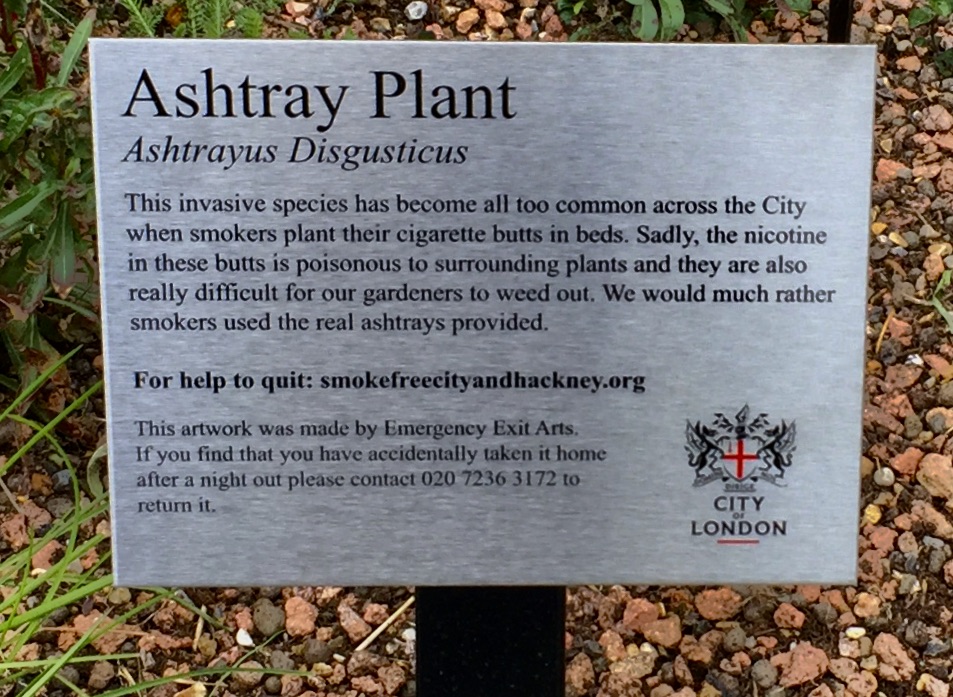

Speak to any one of the wonderful team of City gardeners and they will tell you that one of the greatest threats to their work are smokers discarding cigarette butts in flower beds. Nicotine is poisonous to plants and is a component of many weed killers.

So the City is fighting back using humour …

The final paragraph on the accompanying sign made me laugh out loud …

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …