Why has this 19th century drinking fountain got a carving on it that looks a bit like a Christmas cracker?

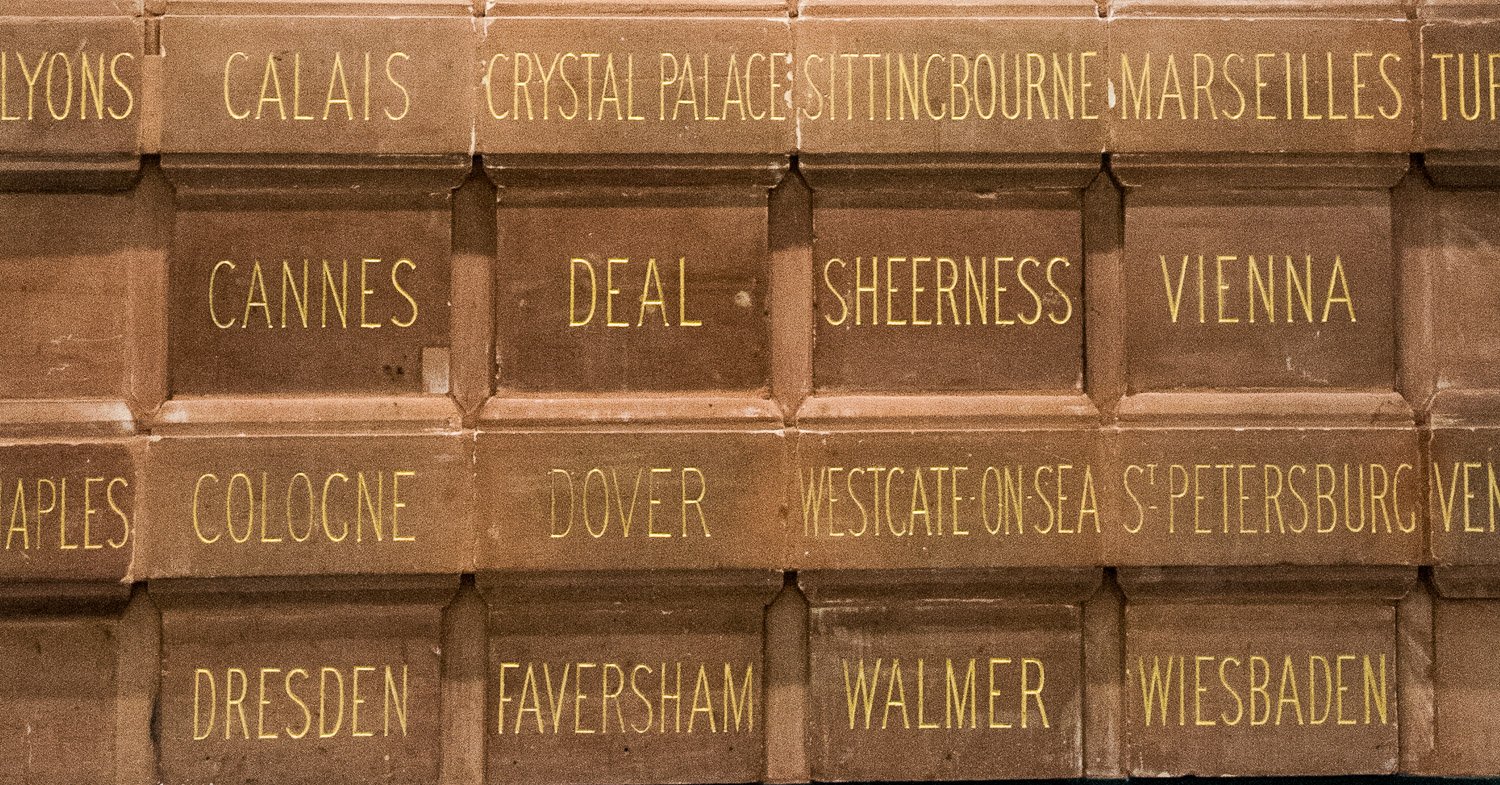

It’s located on the south west side of Finsbury Square and forms part of an elaborate memorial …

The inscription reads …

Erected and presented to the Parish of St Luke by Thomas and Walter Smith (Tom Smith and Co) to commemorate the life of their mother, Martha Smith, 1826 – 1898.

Martha was the widow of Tom Smith and here I would like to relate a little history courtesy of the excellent London Remembers website. In 1847, twenty five year old Tom, an ornamental confectionery retailer in Goswell Road, brought the French idea of a bon-bon wrapped in a twist of paper over to Britain. In 1861, probably inspired by fireworks, he introduced a new product line, ‘le cosaque’, or the ‘Bang of Expectation’, or crackers as we now know them. This successful product, originally used to celebrate any event you care to name, enabled the business to move to larger premises on Finsbury Square, where they stayed until 1953.

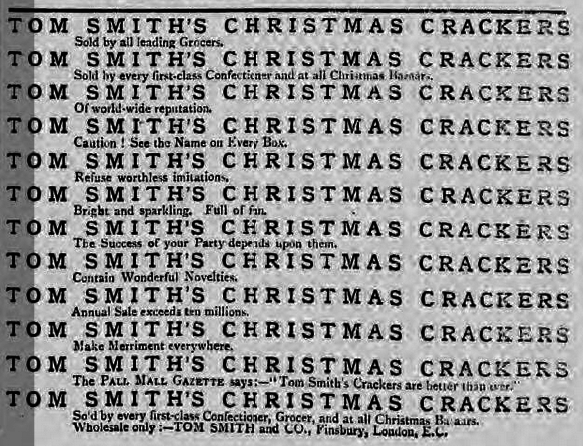

Smith and his sons knew a thing or two about advertising and were not modest about their wonderful products. Here’s a typical 19th century example …

I love the instructions to ‘Refuse worthless imitations’ and ‘Make Merriment everywhere’.

There is an example of a Tom Smith’s Cracker and box on display in the Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green. This picture was taken by The Londonist who has written a very comprehensive blog about the memorial which you can find here …

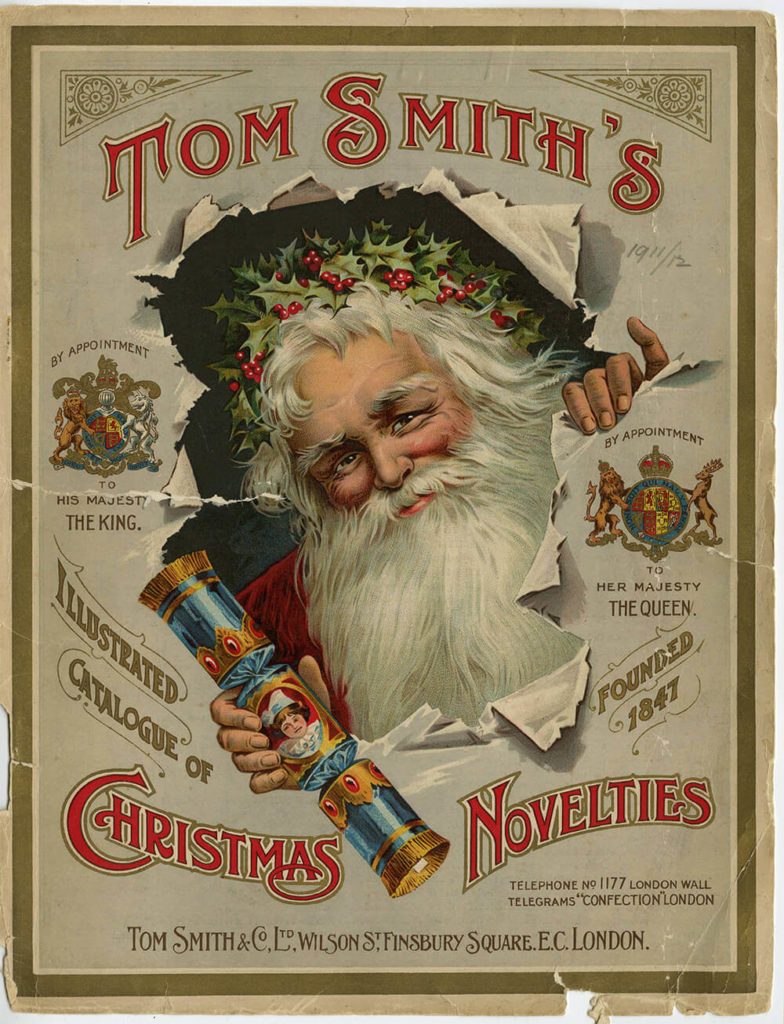

And here is an image from the Tom Smith archive where you can also find the 2019 catalogue and order your Christmas supplies!

Here’s the founder himself. He was born 1823 and died, quite young, in 1869 …

We can thank the company for going on to develop cracker contents like the novelty gift and corny joke. You also have to blame one of Tom’s sons for the paper hat we are obliged to wear, often with excruciating British embarrassment, at work Christmas parties.

Crackers never took off in America and it has been claimed that the British liked them because ‘it taught their children how to deal with disappointment at an early age’.

And now for something rather odd. The water fountain was funded by the sons but the daughters went their own way. A few yards away is this horse and cattle trough …

It bears the following inscription (now very faded) …

In remembrance Martha Smith 1898. Erected by her daughters P. L. and L. D.

The sons erect the splendid water fountain and the daughters erect the utilitarian water trough. Does this tell us something about their personalities or about Victorian gender differences?

Researching the origin of the Christmas cracker has been a genuine pleasure and if you want to know more there is a book about the ‘King of Crackers’ – I might just order a copy. You can find a review here.

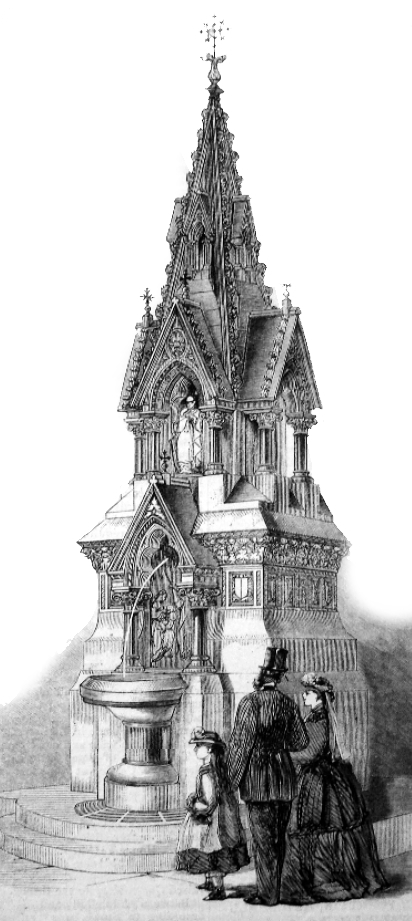

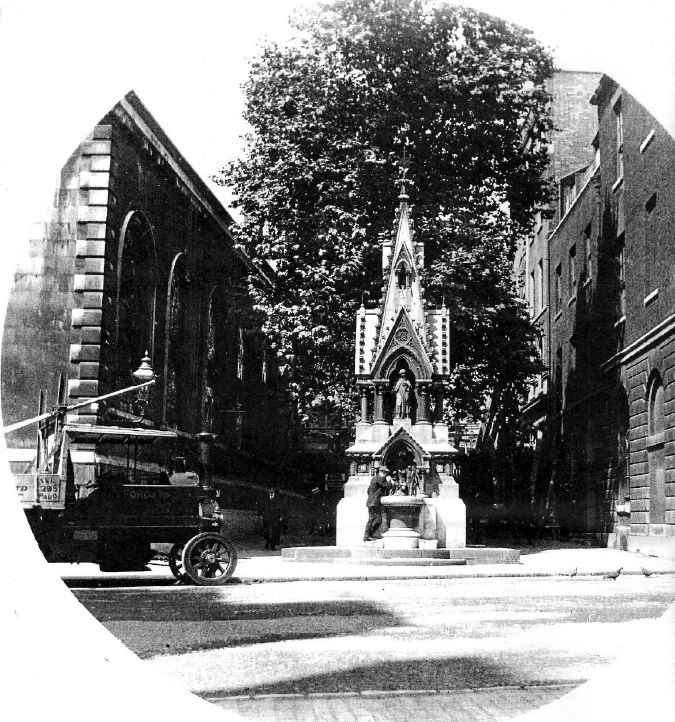

Next up is the St Lawrence and Mary Magdalene fountain located on Carter Lane opposite St Paul’s Cathedral. Created as a joint enterprise between the two parishes that give it its name, the fountain was originally installed in 1866 outside the Church of St Lawrence Jewry …

The location next to St Lawrence Jewry …

It was dismantled in 1970 and put into a city vault for fifteen years, then stored in a barn at a farm in Epping. The pieces were sent to a foundry in Chichester for reassembly in 2009 and it was was moved to the current location the following year …

The work was designed by the architect John Robinson (1829-1912) and sculpted by Joseph Durham (1814-1877), both very famous men in their time.

The fountain takes the form of a niche with carved hood resting on granite columns. Set into the niche is a bronze bas-relief of Moses striking the rock at Horeb (Exodus. XVII. IV-VI) …

Water runs down the face of the bronze from where Moses’ staff strikes. To the left of Moses is the figure of a woman holding a cup of water to her child’s mouth.

Above the fountain is a carved stone statue of St Lawrence holding a gridiron (on which he was martyred) …

In the south-facing niche is a statue of St Mary Magdalene holding a cross, and with a skull at her feet …

The other two niches are empty but are believed to have originally held the names of past benefactors of the churches carved into white marble slabs. Below, a new brass tap has now been fitted which dispenses water when pressed.

I wrote about the City’s water fountains and their fascinating history a few years ago and you can read the blog again here.