Doing photography for my blog isn’t an essential journey, so I hope you won’t mind if I republish an earlier edition, the one reporting on my visit to the Charterhouse. The buildings are in Charterhouse Square (EC1M 6AN) just opposite Florin Court, the flats used as ‘Whitehaven Mansions’ in the Poirot TV series.

A Carthusian monastery had existed on this site since 1371, but catastrophe came in 1535 when the monks were asked to sign an oath acknowledging the King – Henry VIII – as the supreme head of the Church of England. Many refused, and on 4th May that year the Prior, John Houghton, a monk and a lay brother, were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. Houghton’s right arm was chopped off and hung over the Charterhouse entrance gate – a symbol of what happened to those refusing to acknowledge the King’s authority.

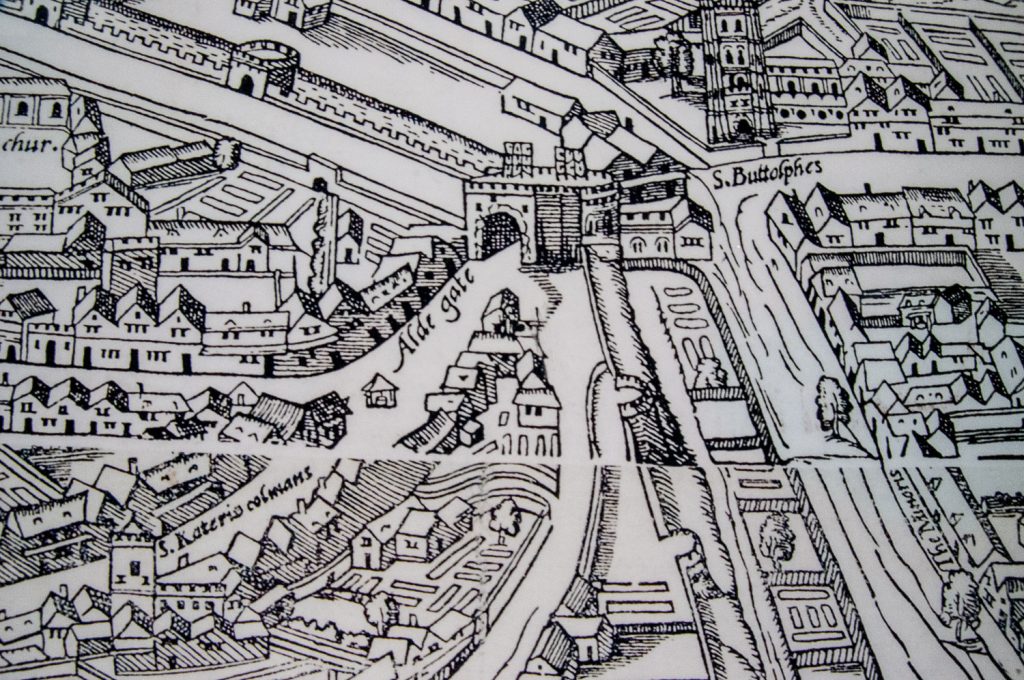

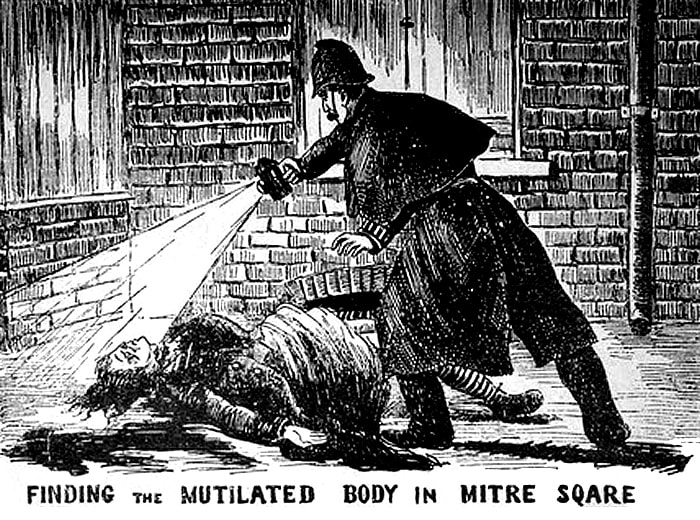

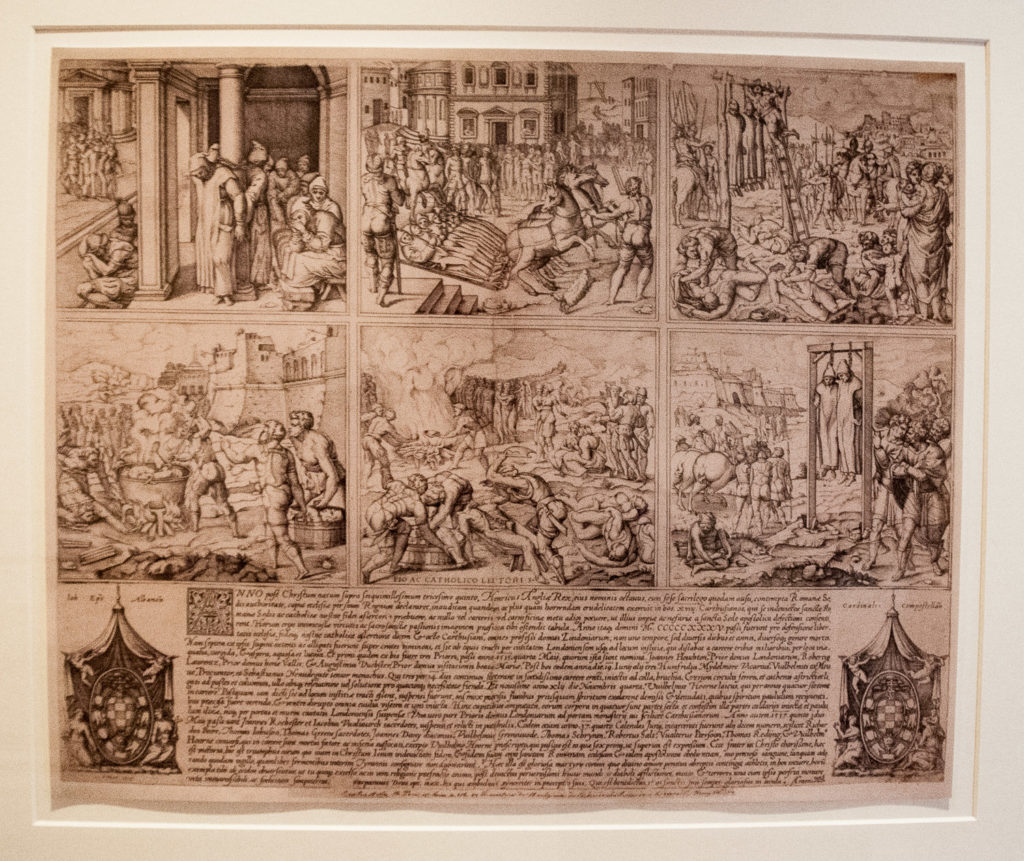

One of the many fascinating things to see on a modern-day tour is this engraving …

The print was produced in Rome about 20 years later. Five of the scenes show the monks imprisoned, dragged through the streets and then being executed. The final scene shows two Carthusian monks being executed in York.

Charterhouse has passed through many incarnations over the centuries and evidence of this abounds to this day.

We can still see the entrance to one of the two-up two-down cells the monks occupied …

Each monk lived as a hermit, spending their time in prayer, contemplation and scholarly work. They seldom spoke, usually only meeting together for Sunday lunch.

Sir Edward North (later Baron North) bought the ransacked property in 1545 and turned it into a mansion. To describe North (1496-1564) as a ‘survivor’ in this tumultuous period would be an understatement – somehow remaining in favour with both Queen Mary and later Queen Elizabeth I. In fact three other owners of Charterhouse (John Dudley, Thomas Howard and Philip Howard) were all executed for treason.

Thomas Howard, the Fourth Duke of Norfolk, bought the buildings in 1564. He rebuilt what is now called the Norfolk Cloister, from the ruins of the monks’ original Great Cloister …

It was in King James’s reign in 1611 that a former ‘Master of the Ordnance in the Northern Parts’, Thomas Sutton, said to be England’s wealthiest commoner, bought the property and established a foundation to maintain a school and almshouses. The school, for 40 boys, was the beginning of Charterhouse School. Later, John Wesley and William Makepeace Thackeray were pupils. In 1872, the school moved to Godalming, taking the young Robert Baden-Powell to complete his schooling in Surrey.

In the Hall, Sutton’s coat of arms can be seen above this magnificent Caen stone chimneypiece, the cannon and gunpowder barrels at the sides referencing his connection with The Ordnance …

The arms include the head of a hunting dog, a Talbot, now extinct. It’s a motif that can be found throughout the building …

In Wash House Court, Tudor bricks meet Monastery stone …

Above the entrance to the passageway to the Court, a tiny monk has found a quiet place to study his Bible …

The buildings were severely damaged by incendiary bombs during the Second World War …

The Chapel contains Thomas Sutton’s spectacular monument …

A relief panel shows the Poor Brothers in their gowns and a body of pious men and boys (perhaps scholars) listening to a sermon …

I love the figure, Vanitas, blowing bubbles and representing the ephemeral quality of worldly pleasure. The figure with the scythe is Time …

The man himself …

By way of contrast we can also see, in a darkened room lit by candles, this poor soul. Uncovered during the Crossrail tunneling, archeologists found it belonged to a man in the prime of his life, in his mid-twenties, when he was struck down by the Black Death. It’s believed he died at some point between 1348 and 1349, at the height of the pandemic …

Thomas Sutton’s will provided for up to 80 residents (called Brothers): ‘either decrepit or old captaynes either at sea or at land, maimed or disabled soldiers, merchants fallen on hard times, those ruined by shipwreck or other calamity’.

A community of some 40 Brothers (as of 2016, women are not excluded by this term) still live in the Charterhouse today.

This blog only covers a tiny example of what you will discover at the Charterhouse. I highly recommend the tours that are conducted every day except Monday. Some are led by one of the resident Brothers and are given from the perspective of each individual Brother, therefore no two tours are the same. Click here for details.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram :