Since I started this blog almost four years ago I must have looked at hundreds of tombs, gravestones and memorials and I have been out again recently adding to my collection. These are some of my favourites with my reason for choosing them. I know times are tough at the moment but although this week’s blog is about dead people I will try to keep it interesting, positive and even maybe a little upbeat!

First up is this stone in the Bow Lane churchyard of St Mary Aldermary. It wins my award for attention to detail. I have never seen actual time of death recorded before …

There is a well preserved coat of arms which seems to include four beavers suggesting involvement in the fur trade which was flourishing at the time.

Under the coat of arms the inscription reads as follows …

Mrs Anna Catharina Schneider. Died 15th of June 1798 at half past Six O’clock in the Evening. Aged 57 Years, 3 months and 9 Days

Her husband’s details, also on the stone, are more basic …

Also John Henry Schneider, Husband of the above Anna Catharina, Died 6th of October 1824 in the 82nd year of his age

I have been trying to find out a bit more about them and I came across a few tantalising details. The London Metropolitan Archives of the City of London have a record of a John Henry Schneider & Company, Merchants, in Bow Lane – surely the same person. It records the company insuring its premises on 29th October 1791. A Wikipedia search throws up a John Henry Powell Schneider (circa 1768 – 1862) and describes him as a ‘merchant of Swiss origin’. I can’t help but speculate that he was Catharina and John Henry’s son. He certainly enjoyed a long life.

From a memorial displaying extraordinary accuracy to one where the date of death is not recorded at all. This gets my ‘oh dear, what happened there’ award.

The earliest memorial in the church of St Dunstan-in-the-West consists of these two brass kneeling figures commemorating Henry Dacres and his wife Elizabeth …

Elizabeth died in 1530 and Henry nine years later. His will tells us that the brass was already made before he died and ‘made at myn owne costes to the honour of almighty god and the blessed sacrament’. Unfortunately it seems he made no arrangement for his actual date of death to be included later and so the date on the plaque is blank and it reads …

Here lyeth buryed the body of Henry Dacres, Cetezen and Marchant Taylor and Sumtyme Alderman of London, and Elizabeth his Wyffe, the whych Henry decessed the … day of … the yere of our Lord God … and the said Elizabeth decessed the xxii day of Apryll the yere of our Lord God MD and XXX.

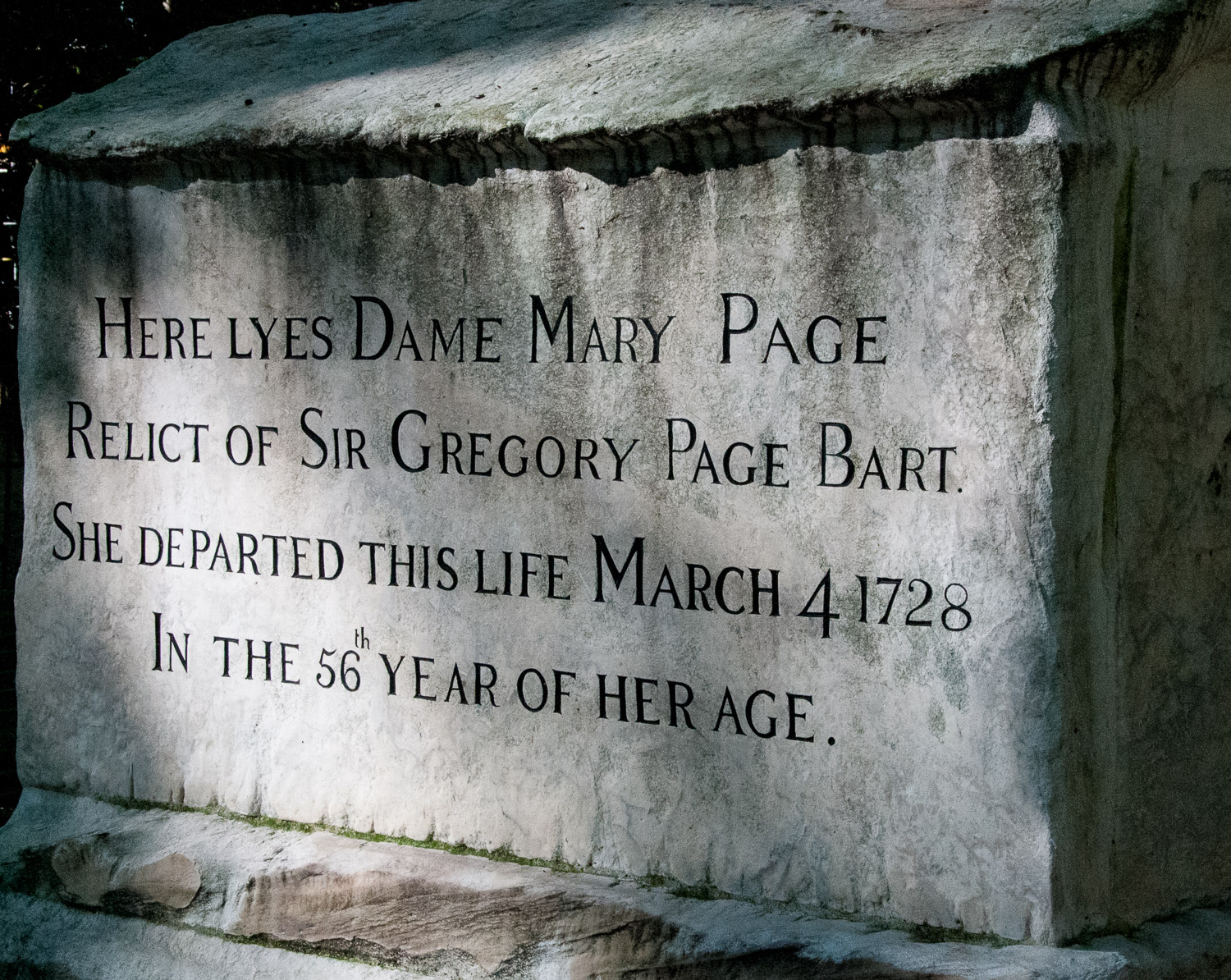

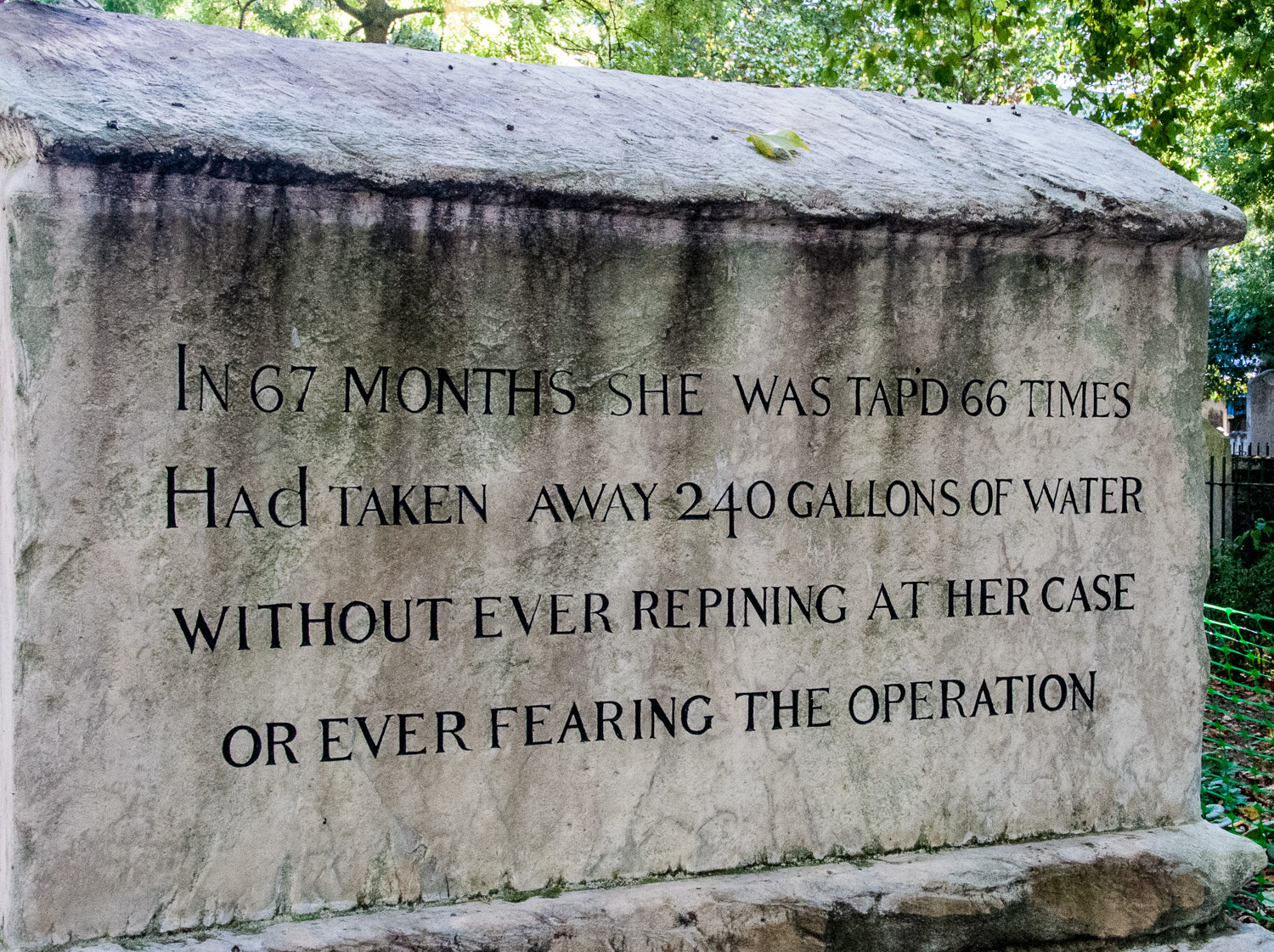

My award for the most interesting medical history must go to Dame Mary Page who has one of the most impressive tombs in Bunhill Fields Burial Ground …

It appears that Mary Page suffered from what is now known as Meigs’ Syndrome and her body had to be ‘tap’d’ to relieve the pressure. She had to undergo this treatment for over five years and was so justifiably proud of her bravery and endurance she left instructions in her will that her tombstone should tell her story. And it does …

When I pointed this out to a friend he remarked ‘for me, that’s a bit too much information’.

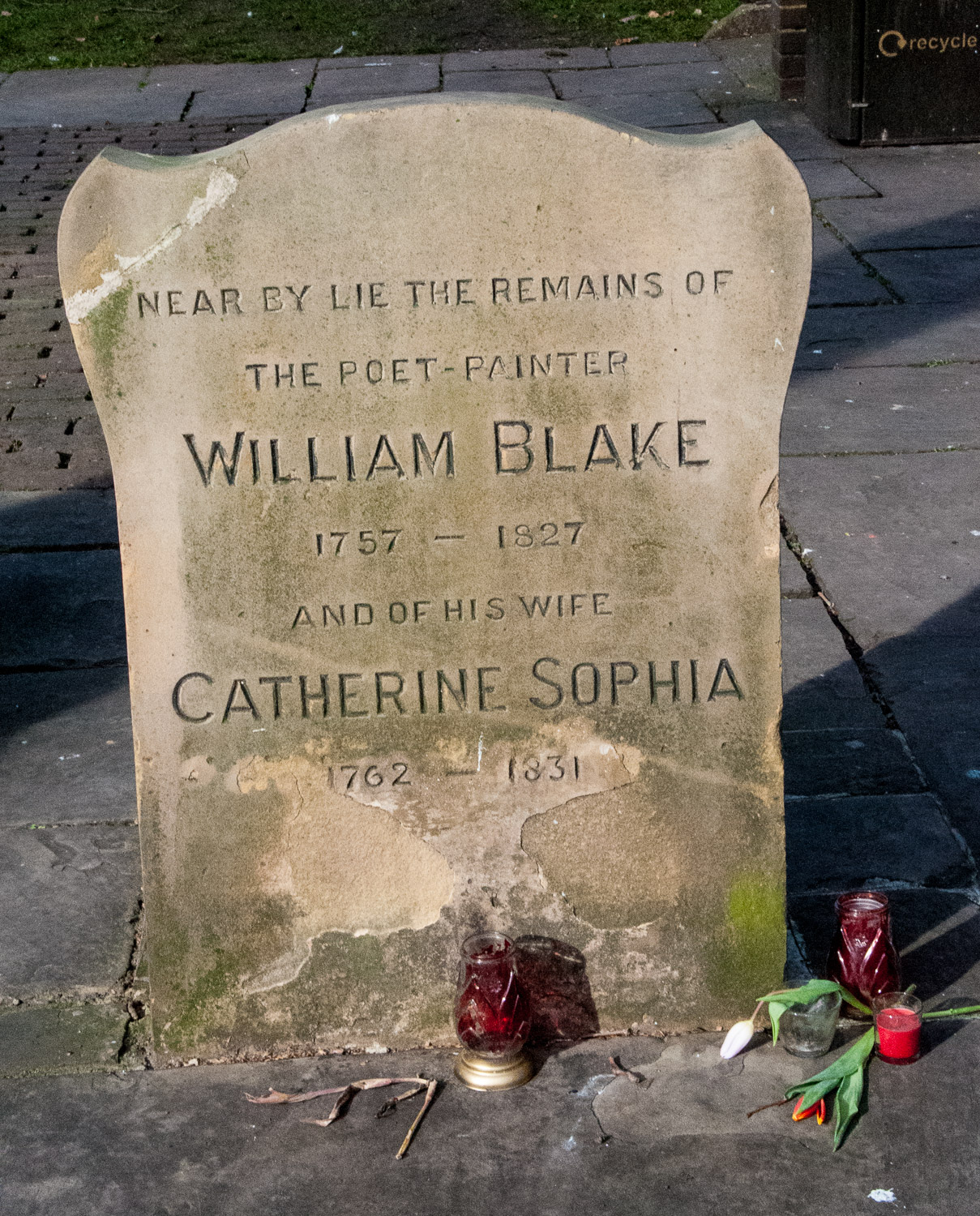

Again located in Bunhill, my award for the most uplifting gravestone story goes to the Blake Society. Until recently the only stone recording the last resting place of William Blake was the one below …

It was originally placed over his actual grave by The Blake Society on the centenary of his death (1927) but it was moved in 1965 when the area was cleared to create a more public open space. Considered mad by many of his contemporaries, he is now regarded as one of Britain’s greatest artists and poets, his most famous work probably being the short poem And did those feet in ancient time. It is now best known as the anthem Jerusalem and includes the words that are often cited when people refer to workplaces of the Industrial Revolution …

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

The present day Blake Society finally traced again where he was actually buried and in August 2018 a beautiful stone was placed over his final resting place exactly 191 years after his death …

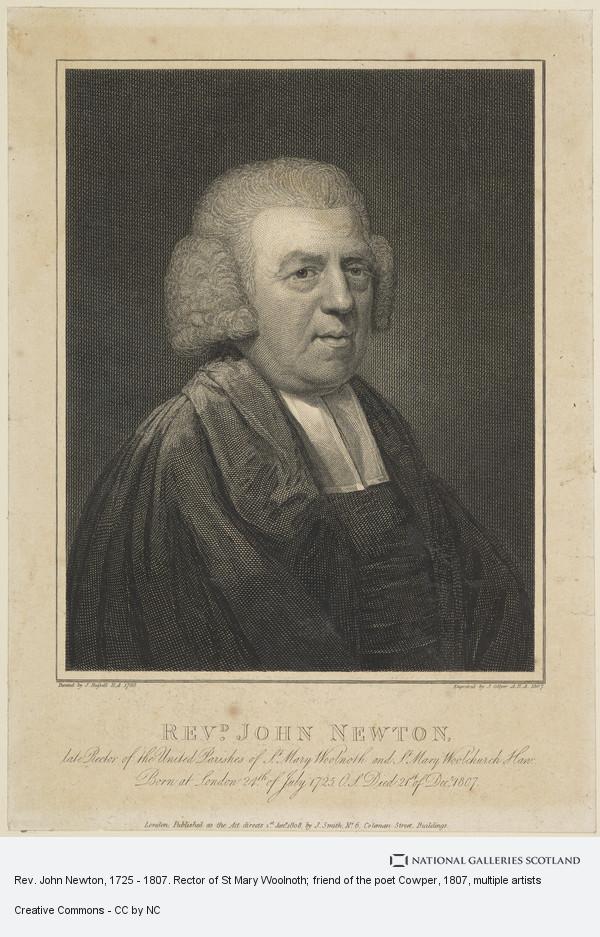

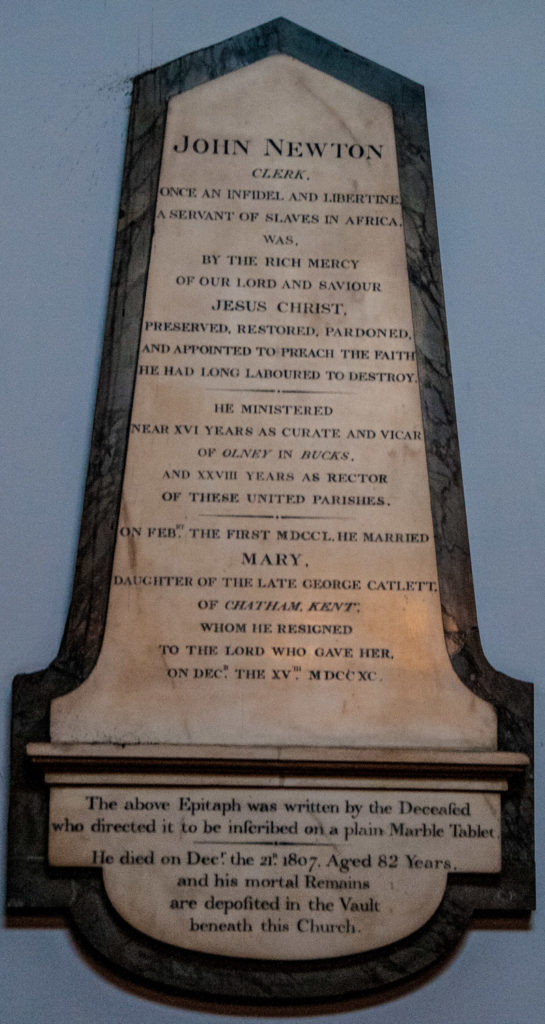

Lots of memorials attempt to draw attention to the key characteristics and achievements of the person immortalised. My award for most interesting life history goes to this gentleman commemorated in the church St Mary Woolnoth where he served as rector, John Newton …

Born the son of a master mariner in Wapping, he spent the early part of his career as a slave trader. From 1745-1754 he worked on slave ships, serving as captain on three voyages. He was involved in every aspect of the slaver’s trade, and his log books record the torture of rebellious slaves. Following his conversion to devout Christianity in 1748 he eventually became rector at St Mary’s in 1780. In the church is his memorial tablet, which he wrote himself beginning …

John Newton, Clerk, once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa …

In 1785, he became a friend and counsellor to William Wilberforce and was very influential himself in the abolition of slavery. He lived just long enough to see the Abolition Act passed into law. Think of him also when you hear the hymn Amazing Grace, which he co-wrote with the poet William Cowper in 1773.

My award for being absolutely spectacular must go to Thomas Sutton’s tomb in the chapel at the Charterhouse …

A relief panel shows the Poor Brothers in their gowns and a body of pious men and boys (perhaps scholars) listening to a sermon …

I love the plump figure, Vanitas, blowing bubbles and representing the ephemeral quality of worldly pleasure. The figure with the scythe is, of course, Time …

The man himself …

Incidentally, by way of contrast we can also see, in a darkened room lit by candles, this poor soul. Uncovered during the Crossrail tunneling, archeologists found it belonged to a man in the prime of his life, in his mid-twenties, when he was struck down by the Black Death. It’s believed he died at some point between 1348 and 1349, at the height of the pandemic …

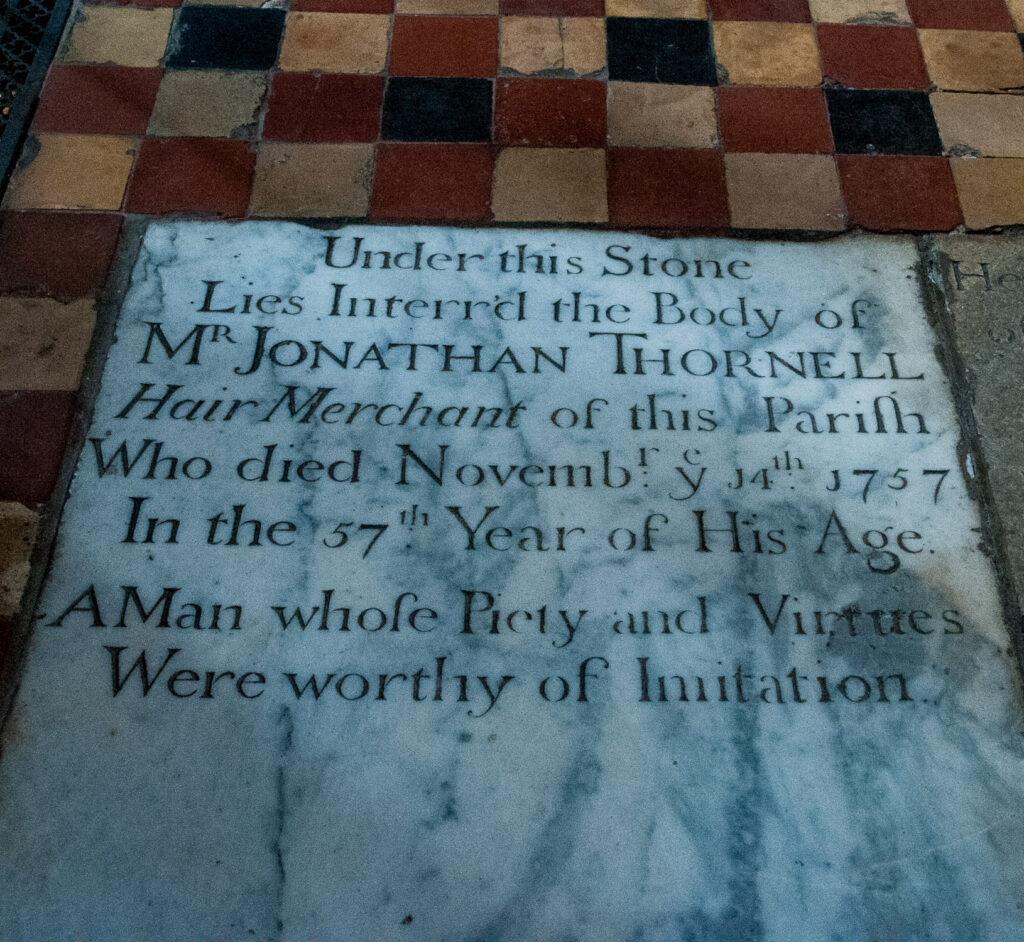

Many memorials state the occupation of the deceased and my award for one of the most interesting as a reflection of the times is the tombstone of the hair merchant Mr Jonathan Thornell in St Bartholomew the Great …

To be buried inside the church indicated that he was a wealthy man and this was no doubt because, in the 18th century, wigs of all varieties were tremendously fashionable. Good hair was seen as a sign of health, youth and beauty and merchants like Mr Thornell often travelled the country looking for supplies (even buying it off the head of those needy enough to sell it).

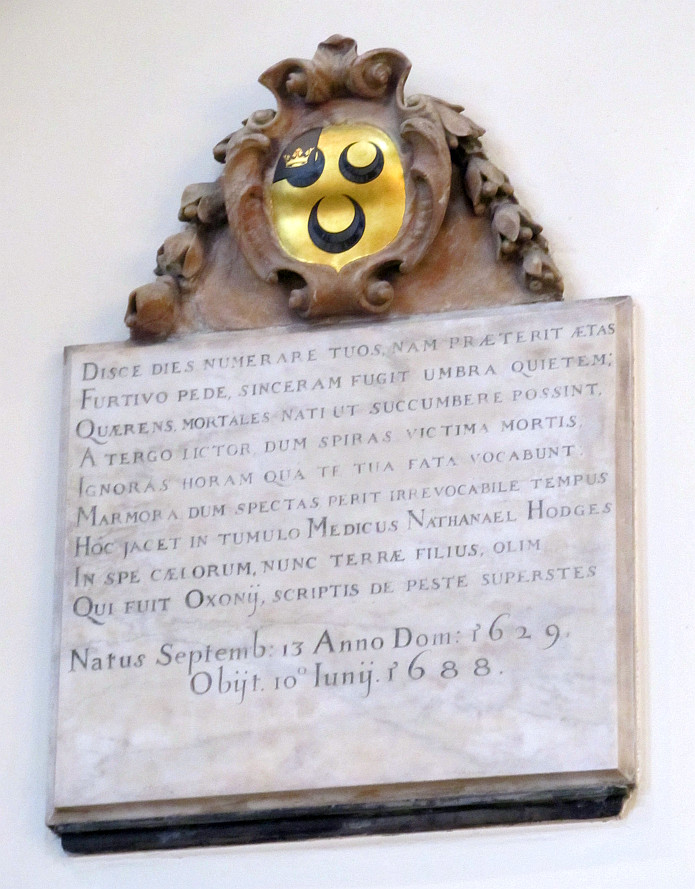

Finally, lots of brave deeds are recorded in city churches but one of the people I most admire is commemorated in St Stephen Walbrook, Dr Nathaniel Hodges …

His memorial is on the north wall and this is a translation from the Latin …

Learn to number thy days, for age advances with furtive step, the shadow never truly rests. Seeking mortals born that they might succumb, the executioner [comes] from behind. While you breathe [you are] a victim of death; you know not the hour which your faith will call you. While you look at monuments, time passes irrevocably. In this tomb is laid the physician Nathaniel Hodges in the hope of Heaven; now a son of earth, who was once [a son] of Oxford. May you survive the plague [by] his writings. Born: September 13, AD 1629 Died, 1o June 1688

Unlike many physicians, Dr Hodges stayed in London throughout the time of the terrible plague of 1665.

First thing every morning before breakfast he spent two or three hours with his patients. He wrote later …

Some (had) ulcers yet uncured and others … under the first symptoms of seizure all of which I endeavoured to dispatch with all possible care …

hardly any children escaped; and it was not uncommon to see an Inheritance pass successively to three or four Heirs in as many Days.

After hours of visiting victims where they lived he walked home and, after dinner, saw more patients until nine at night and sometimes later.

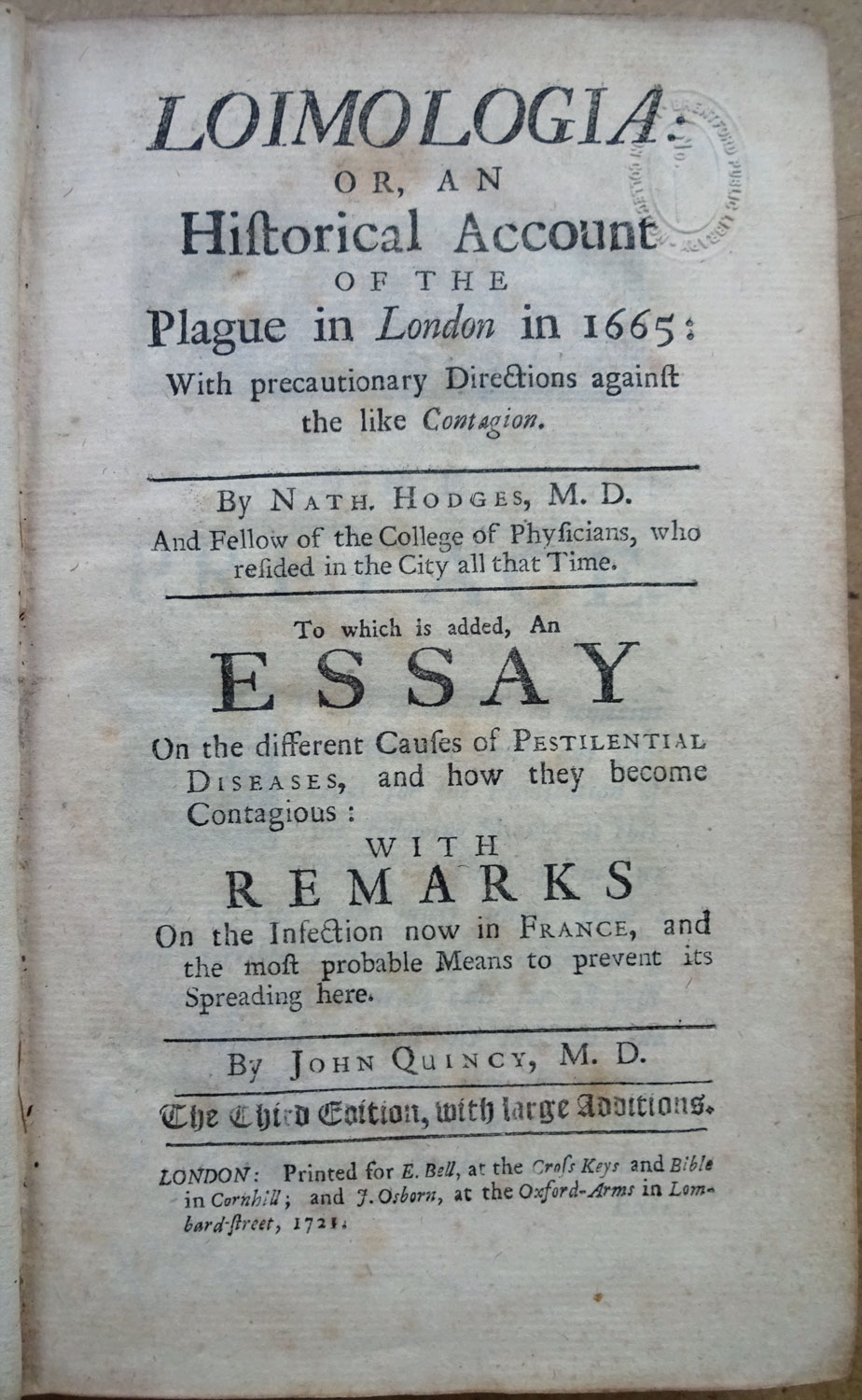

He survived the epidemic and wrote two learned works on the plague. The first, in 1666, he called An Account of the first Rise, Progress, Symptoms and Cure of the Plague being a Letter from Dr Hodges to a Person of Quality. The second was Loimologia, published six years later …

Above is a later edition of Dr Hodges’ work, translated from the original Latin and published when the plague had broken out in France.

It seems particularly sad to report that his life ended in personal tragedy when, in his early fifties, his practice dwindled and fell away. Finally he was arrested as a debtor, committed to Ludgate Prison, and died there, a broken man, in 1688.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …