My two Roman London blogs this month are in celebration of the opening of the London Mithraeum in Bloomberg Space, Walbrook, which I enjoyed tremendously when I visited last week.

If you want to immerse yourself more completely in the Mithras Temple story, you might like to call in to the Museum of London beforehand and view the treasures there from the Walbrook excavation. I have put together a small selection.

There is this head of Mithras …

Head of Mithras, marble, late 2nd century

He is shown as a handsome youth, the head probaly part of a large sculpture forming a focal point at the apse end of the Temple.

Serapis, the Egyptian God of the Underworld, was also represented …

Head of Serapis, marble, late 2nd – early 3rd century

He carries a corn measure on his head symbolising the wealth and fertility of the earth.

And Minerva, the Roman Goddess of Wisdom …

Head of Minerva, marble, early 2nd century, possibly AD 130

Again, the head was probably originally part of a larger statue.

So now on to the Mithraeum itself at 12 Walbrook. Entry is free but you must book a time slot in advance using the website.

The first thing you see is this stunning tapestry by Isabel Nolan …

Another View from Nowhen, 2017

There are helpful guides ready, and very willing, to introduce you to the Mithraeum, explain the tapestry and an accompanying sculpture, and hand you an excellent printed guide. There is a well organised display of Roman artefacts which can be explored using your own mobile device, a tablet that they provide, or just by reading the labels. Unfortunately I couldn’t get a good enough photograph of these for the blog – please take my word for it that they are fascinating.

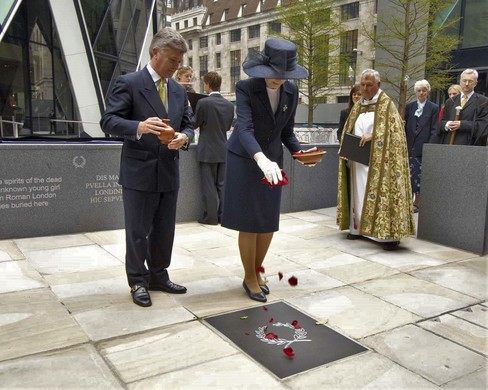

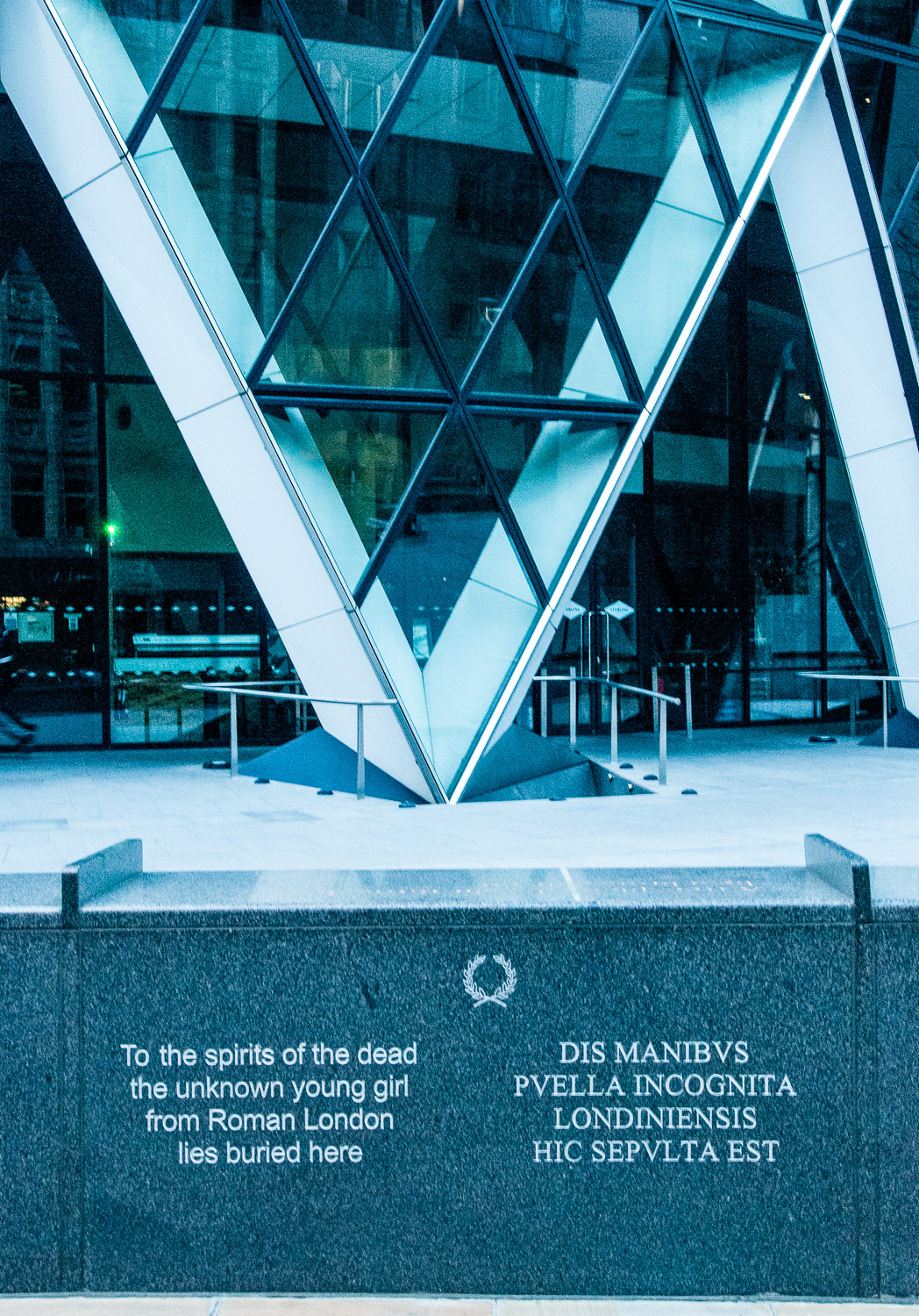

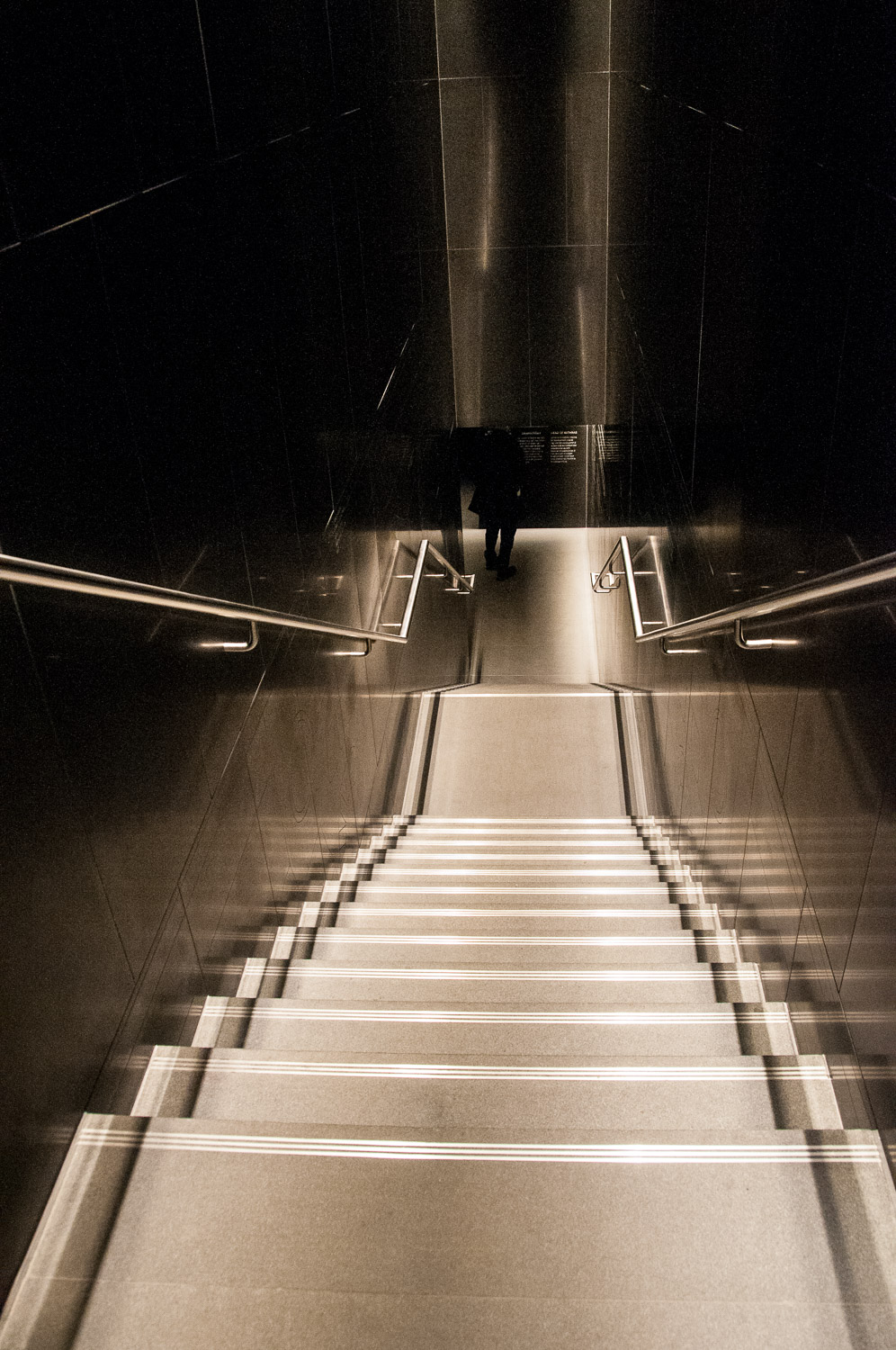

Then you are ready to descend through time, seven metres or so, from modern London to the very last days of the Romans in Britain, about AD 410.

Various levels of history are inscribed on the wall as you descend – there is also step-free access

At mezzanine level there is a further exhibition consisting of a reproduction of artefacts from the site including, of course, the head of Mithras, and a helpful commentary.

You then descend further to see the Temple itself. Initially it is dark and shrouded in mist but, as this gradually clears to the sound of evocative chants, you will see an accurate reconstruction of the ruin as it was on the last day of excavation in October 1954.

All the stone that you see and most of the bricks are from the original structure

The central icon of the cult is Mithras killing a bull

All I can say is ‘well done Bloomberg’.

The Walbrook stream played a very important part in the establishment of Roman London. Originating in what is now Finsbury Park, it carried fresh water in to the walled City and carried waste away to the River Thames. As the City developed it became imprisoned underground.

The stream lives on in the name of the street

The area has been difficult to access lately because of construction work, but is now a new open space and I took the opportunity to explore.

What a wonderful surprise! It looks like the Walbrook is flowing again above ground through the City…

Alongside Cannon Street

Parallel to Queen Victoria Street

Entitled Forgotten Streams, and cast in bronze, the Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias took as her inspiration the ancient Walbrook itself. It looks very authentic and quite beautiful.

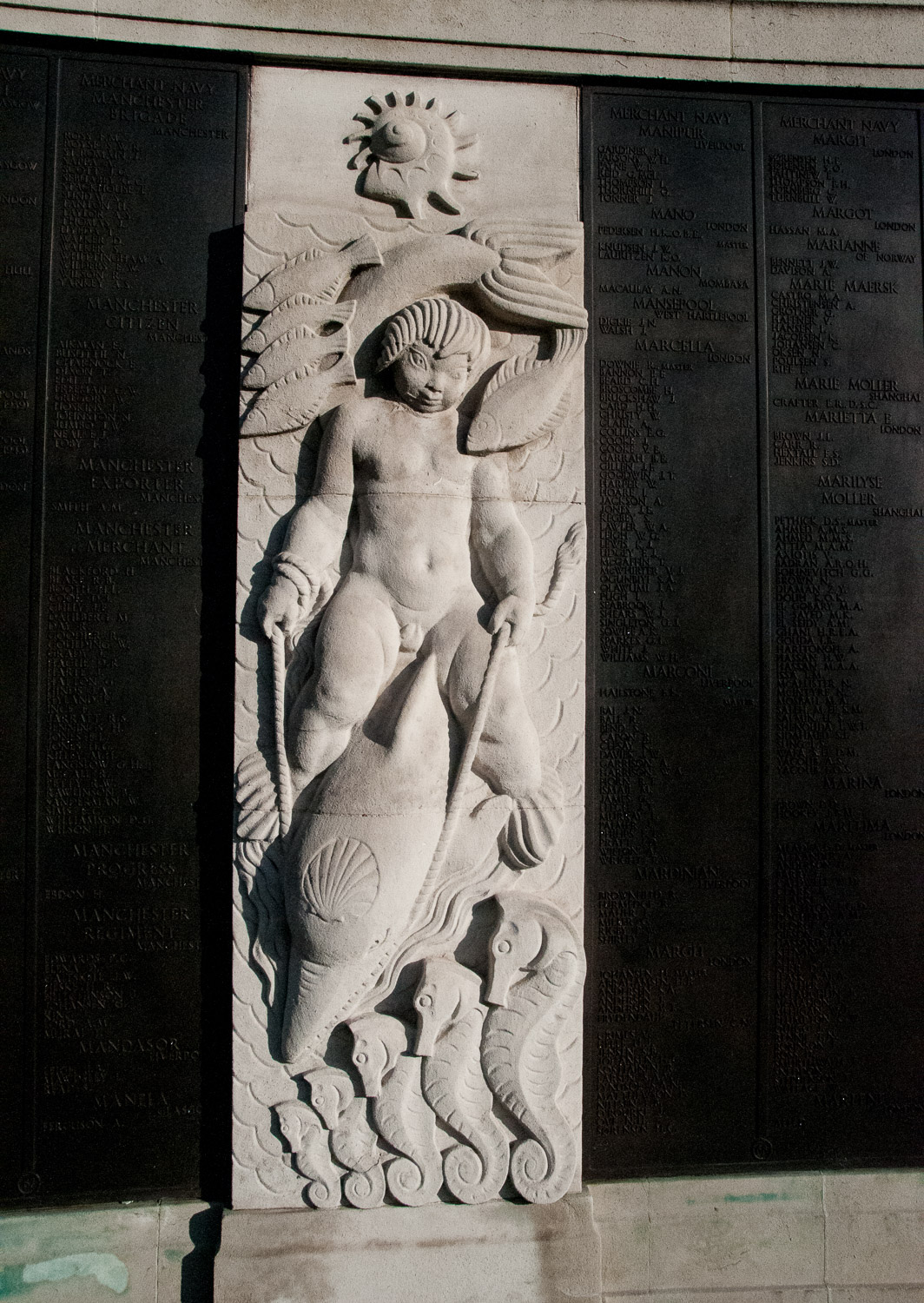

And finally, to complete a Roman London experience, you might want to visit the Guildhall Art Gallery, in the lower level of which you will find Roman London’s Amphitheatre. An 80 metre wide curve of dark stone in Guildhall Yard marks out the area of the Amphitheatre, the site of the famous Roman ‘Games’ …

An outline of what existed about 8 metres below

The site of the Amphitheatre

Once inside you will see the remains of the original walls, the drainage system, and a rather impressive digital projection that fills in the gaps in the ruins.