William Sanson, a London auxiliary fireman, thought 7th September 1940 ‘one of the fairest days of the century, a day of clean warm air and high blue skies’. At 4:00 pm that afternoon, just across the Channel at Cap Blanc Nez, the commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe Hermann Göring was also enjoying the sunshine. From there he watched as 348 German bombers headed for London accompanied by an escort of 617 fighters. Looking up, Londoners who had not taken shelter could see this vast force some two miles high and 20 miles wide – they seemed to blot out the sun. London was pounded until 6:00 pm. Two hours later, guided by the fires set by the first assault, a second group of raiders commenced another attack that lasted until 4:30 the following morning. The raids continued for 56 out of the following 57 days and nights. Sanson and his brave colleagues were no longer mocked as ‘army dodgers’ (who restaurants often refused to serve) but were re-christened as ‘heroes with grimy faces’.

Thanks to the efforts of the fire services and volunteers, many City churches survived the Blitz although some, such as St. Mary-le-Bow, had to be substantially rebuilt. Others were effectively lost apart from their towers and today’s blog visits the four of them that were originally designed by Sir Christopher Wren, assisted by Nicholas Hawksmoor.

In Wood Street, just opposite the police station, stands the tower of St Alban’s. It’s a church designed by Wren in a late Perpendicular Gothic style and completed in 1685 to replace a previous structure destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire.

St Alban, Wood street

The church was restored in 1858-9 by George Gilbert Scott, who added an apse, and the tower pinnacles were added in the 1890s. It was destroyed on a terrible night, 29 December 1940, when the bombing also claimed another eighteen churches and a number of livery halls. Some of St Alban’s walls survived but they were demolished in 1954 and now nothing remains apart from the tower – not even a little garden to give it some cover from the traffic passing on both sides. I’ve often been told someone lives there but I have never seen any evidence of it.

This is St Dunstan-in-the-East on St Dunstan’s Hill, just off Great Tower Street.

The body of the church had been rebuilt in 1821 but the Wren tower was retained and it survived the Blitz whereas the church did not. It is said that Wren had such confidence in its construction that, when told the steeples of every City church had been damaged in a hurricane that hit London in 1703, he replied ‘Not St Dunstan’s, I am sure’.

Where the church stood is now a lovely secluded public garden which is well worth a visit. Horror film aficionados will recognise the tower as the setting for the final scenes of the 1965 movie Children of the Damned when it, and the children, are wiped out by the military.

There are some cute cherubs on the west door, one of them fast asleep …

‘Wakey-wakey!’

The St Dunstan cherubs

These walls and the tower are all that remain of Christchurch Greyfriars on the corner of Newgate Street and King Edward Street …

Scorch marks are still visible on the walls. The substantial steeple consists of triple-tiered squares.

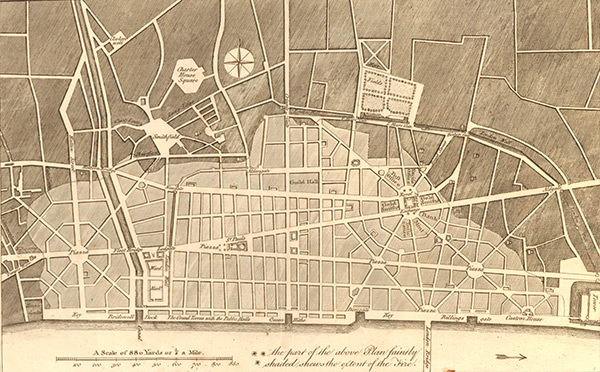

The site of the Franciscan church of Greyfriars was established in 1225. Those considered to be significant enough to be buried in the medieval church included four queens: Joan de la Tour, Queen of Scotland and daughter of Edward II; Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I and one of the church’s original benefactors; Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III (her heart is said to have been interred under the altar); and Queen Isabella, daughter of King Philip IV of France and wife of Edward II (nicknamed ‘the She-Wolf of France’ on account of her plots against her husband). Also buried here, despite having been given a ‘traitor’s death’, was Elizabeth Barton, who was hanged in 1534 for prophesying the death of Henry VIII when he planned to marry Anne Boleyn. The old church was destroyed in the Great Fire and a new church, designed by Wren, was completed in 1704.

Like St Alban Wood street, his church was another victim of the night of 29 December when incendiary bombs created the ‘Second Great Fire of London’ and only the west tower now stands. Incredibly, though, its wooden font is said to have been saved from the flames by a postman and it now stands a few hundred yards away in St Sepulchre-without-Newgate.

Where the main body of the church once was is now a very attractive garden consisting of heavily planted herbaceous borders including a variety of modern repeat-flowering shrub roses and climbers. The wooden towers within the planting replicate the original church towers and host a variety of climbing plants.

The pretty garden at Christchurch Greyfriars

Situated slightly to the east of St Paul’s Cathedral is the tower of St Augustine with St Faith, Watling Street …

I like this view very much – the Cathedral and church tower complement one another beautifully

Rebuilt by Wren in 1682-3 the tower and spire were added in 1695 and are probably by Hawksmoor. The church was bombed to destruction on 9th September 1940 but you will no doubt be pleased to learn that Faith, the church cat, survived and became very well known. Days before she was seen moving her kitten, Panda, to a basement area. Despite being brought back several times, Faith insisted on returning Panda to her refuge. On the morning after the air raid the rector searched through the dangerous ruins for the missing animals, and eventually found Faith, surrounded by smouldering rubble and debris but still guarding the kitten in the spot she had selected three days earlier. Her story reached Maria Dickin, the founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, and for her courage and devotion Faith was awarded a specially-made silver medal. Her death in 1948 was reported around the world. For the full story of Faith I suggest you visit the wonderfully named purr-n-furr UK website and search for Faith, The London Church Cat. There is even a photograph of the famous moggie.

The surviving tower now forms part of the St Paul’s choir school. The new building was awarded the RIBA Architecture Award for London in 1968, being commended particularly for sensitive and intelligent handling of the context.

The Evening News reports on the bombing …

Over 30,000 Londoners died in the World War II air raids and they are commemorated by this understated monument outside the north transept of St Paul’s Cathedral. It was paid for by public funds raised following an appeal in the Evening Standard newspaper, launched in connection with the 50th anniversary of VE Day. The Queen Mother made a personal donation and carried out the unveiling on 11 May 1999.

It is a single piece of Irish limestone sculpted by Sir Richard Kindersley. The words on top, written in a spiral, are taken from Sir Edmund Marsh writing after the Great War, but quoted again by Winston Churchill in his history of the Second World War.

They read as follows

‘In War, Resolution: In Defeat, Defiance: In Victory, Magnanimity: In Peace: Goodwill’

And around the sides

REMEMBER BEFORE GOD, THE PEOPLE OF LONDON 1939-1945

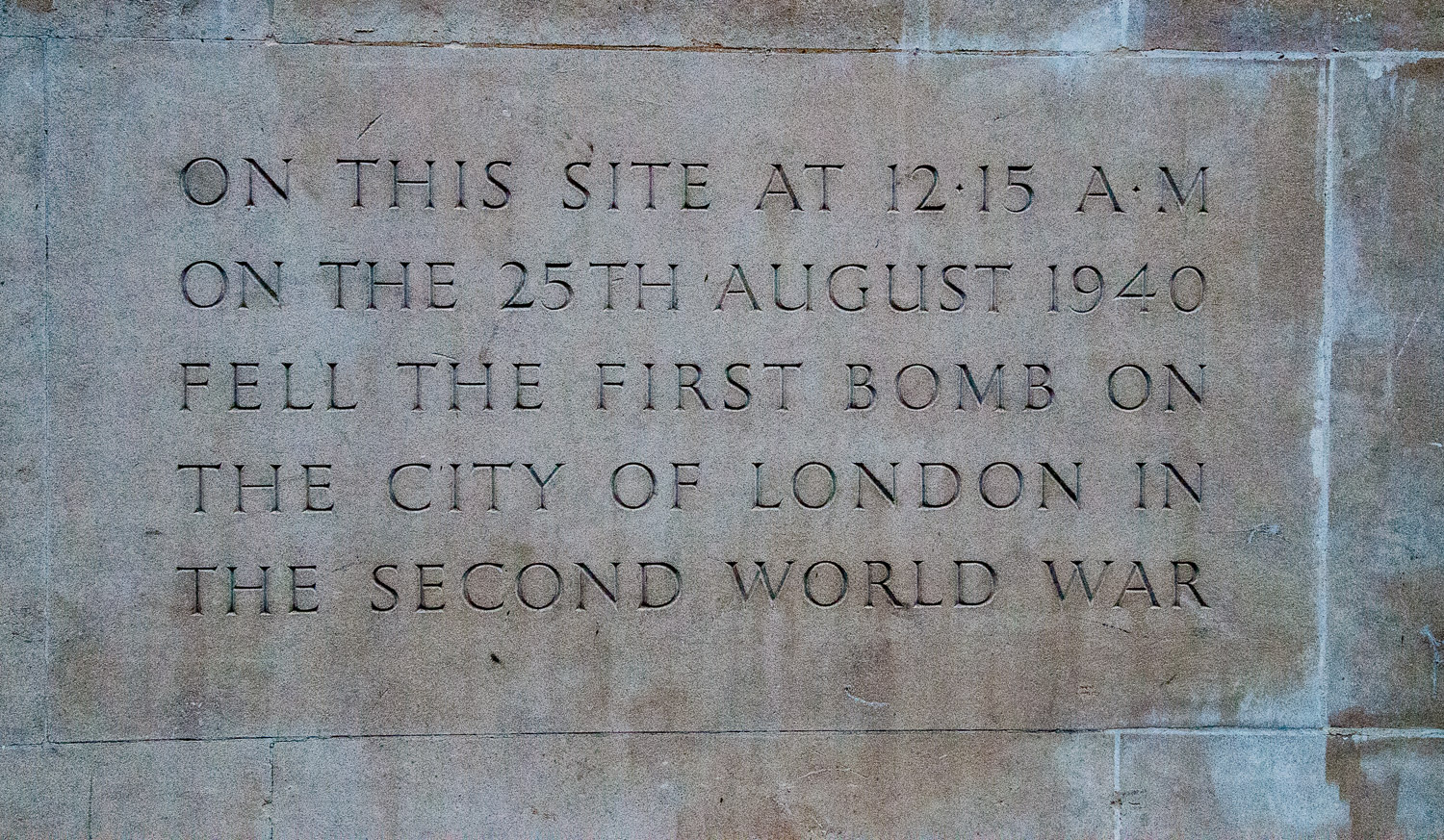

Before the terrible onslaught of the Blitz, the first bomb actually fell on the City early in the morning of 25th August 1940. The event is commemorated by this engraved stone on Roman House at the corner of Wood Street and Fore Street. I only know about this because I can see it from my window in the Barbican!