Mythical dragons do seem to keep finding themselves guarding pretty, captive maidens who are then rescued by brave heroes who slay the poor old dragon. So I thought I would combine dragons and maidens for this blog, especially since the dragon is a well-known symbol of the City of London.

The first thing I must be clear about is that the City symbol is a dragon not a griffin!

I always used to call them griffins and that is how they are described constantly in guides to London but there are differences between the two.

A griffin (or gryphon) is a legendary creature with the body, tail and back legs of a lion; the head and wings of an eagle; and an eagle’s talons as its front feet. I have only been able to find one in the City and here it is …

He proudly supports the arms of the Clothworkers Company.

Dragons, on the other hand, have a serpent’s tail, tend to be scaly all over and breathe fire and smoke. Here is the City of London version …

It is made of cast iron and painted in silver with details picked out in red. It holds a shield with the City emblem of the red cross of St George and the short sword of St Paul and nine of them serve as boundary marks around the City. In addition, there are many other dragons all over the City in a variety of poses.

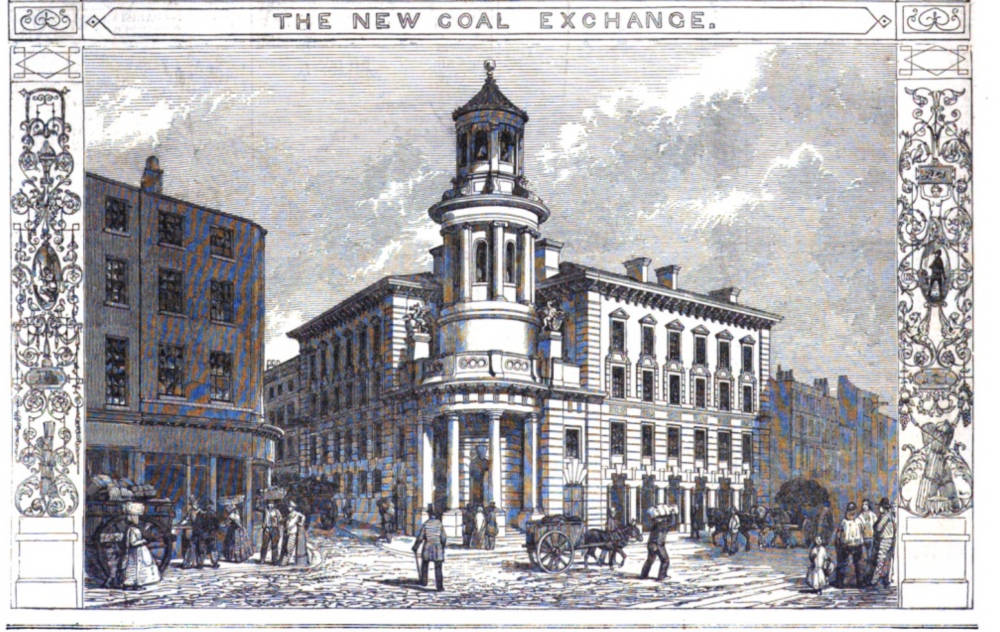

Their original version once graced the 1849 Coal Exchange on Lower Thames Street which was demolished in 1963. The two dragons, however, were relocated to Victoria Embankment in November of that year where they remain to this day and are much bigger than subsequent versions which are about half their size.

Here is an original dragon in his new home on Victoria Embankment…

He looks very sinister in silhouette …

Guarding the boundary between the City of London and Westminster, the Temple Bar Dragon is in a league of its own. It is taller, fiercer, very gothic and is black rather than silver. It would be quite at home in a Harry Potter story and is quite scary – maybe that’s why the Corporation Committee Chairman, having considered the Temple Bar version, chose the less flamboyant Coal Exchange dragons as boundary markers instead.

Another dragon at Temple Bar looks towards Westminster …

This Smithfield beast looks like he is just about to swoop down – perhaps for a meaty lunch …

And these two work hard supporting the roof of Leadenhall Market

And so to maidens – Mercer Maidens to be precise.

The Mercer Company is the first in precedence of the ‘Great Twelve’ livery companies of the City of London and I shall be writing in more detail about the companies in a later blog.

The Mercers’ Maiden symbol is part of the coat of arms of the Company and according to their website she first appears on a seal in 1425. Her precise origins are unknown, and there is no written evidence as to why she was chosen as the Company’s emblem. She is often depicted wearing the fashions of her time since the coat of arms was not granted until 1911 so her appearance often varied.

She was often used to mark buildings belonging to the Company and I have been strolling around the City looking for her.

The inconsistency of design is apparent here with these two maidens only a few feet apart on the same building in Old Jewry.

Here is the Mercer Hall Maiden

And one in Queen Street

And another in Gresham Street, incorporating cornucopia signifying wealth and plenty …

And finally the oldest surviving …

As you can see, she is dated 1669 and was reinstated here after development work in 2004. Serene and beautiful, she must have witnessed much of the rebuilding of the City after the Great Fire of 1666.