Although it doesn’t look it at first glance, the corner of Wood Street and Cheapside is a little historical treasure trove. Here it is today, a card shop, a tree and a bit of open space – and all offer a fascinating sense of continuity with the City’s past.

Copyright Katie at ‘Look up London’

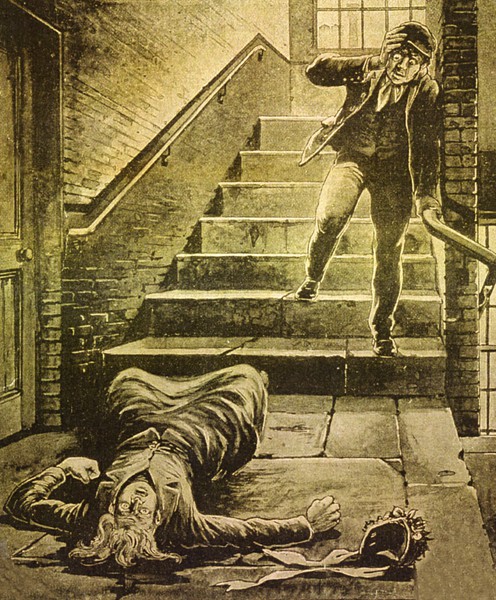

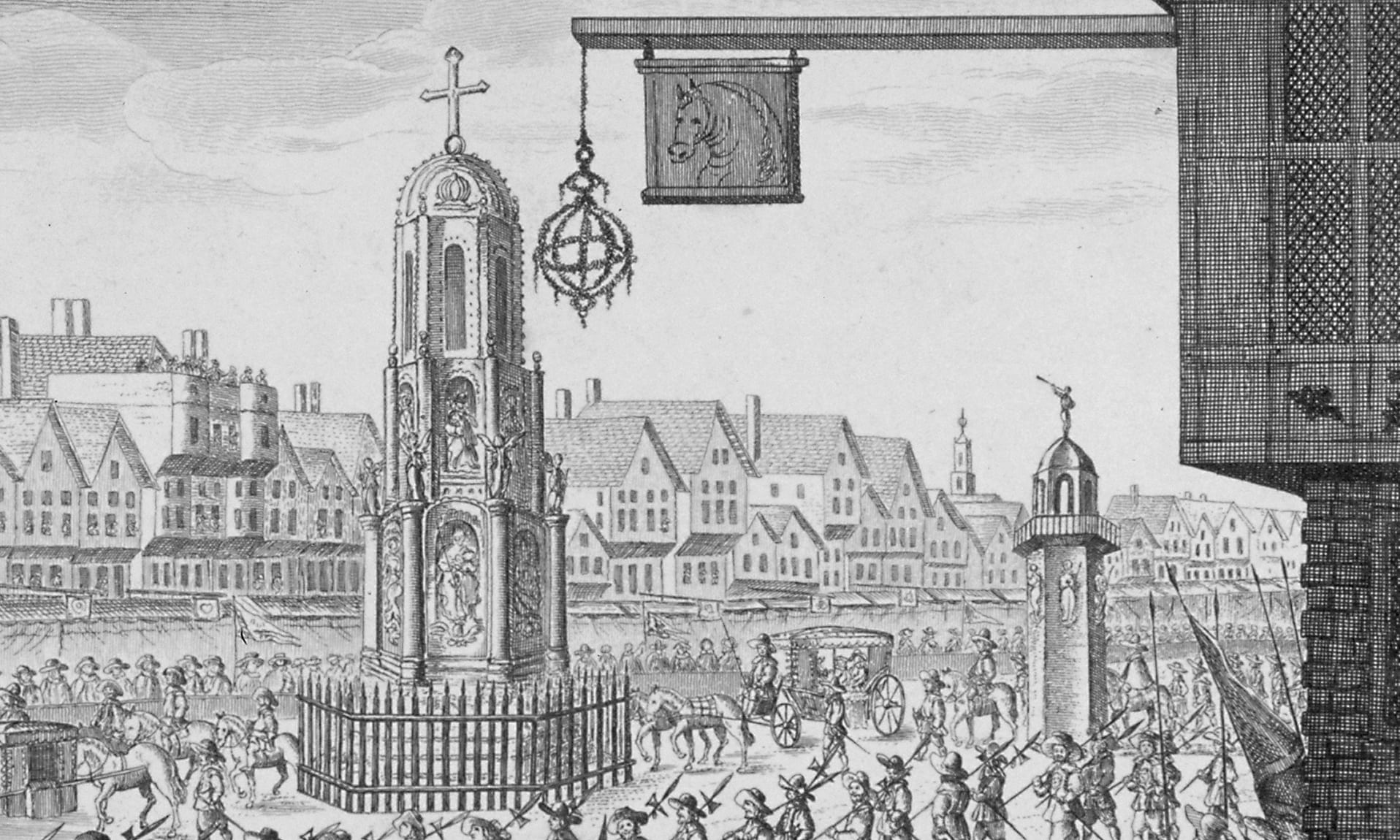

Cheapside had originally been known as West Chepe to distinguish it from East Chepe at the other end of the City and the name comes from the Saxon Ceap, meaning market. For centuries it was a scene of medieval pageantry, being wide enough for horse racing and jousts. It was also a place of grisly executions and the punishment of the likes of errant tradesmen and apprentices, usually utilising the permanent pillory and stocks. Facing Wood Street was the Eleanor Cross, one of a dozen lavish monuments erected by Edward I between 1291 and 1294, in memory of where the coffin of his wife Eleanor of Castile rested overnight as her body was transported to London.

The Cheapside Cross, with the Great Conduit to the right of it. Illustration: Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty

Before its demolition in 1643, the Cross was adjacent to a conduit, one of three providing fresh water piped from the River Tyburn, giving the citizens of London an alternative to the foul water from the wells and the Thames. It was the custom, on days of celebration, for the conduits to run with claret. The historian Bernard Ash observed that it was …

‘Claret undoubtedly as coarse and bloody as the mob which drank it’.

By the beginning of 1666 the street was dominated by traders: mercers, drapers, haberdashers, furriers and also Cheapside’s ‘greatest treasure’, the goldsmiths. Most of the messy, smelly trades had migrated to London’s rim.

As the Great Fire fire spread, people dug desperately into the earth to puncture the conduit’s water supply, hoping the water might quench the flames – in vain – and the Great Conduit itself was razed to the ground along with Cheapside on Tuesday 4 September 1666. A post-fire visitor declared in amazement …

‘You may stand in Cheapside and see the Thames!’

I would like to start my story with the little shop on the corner, which I have been tracking through time …

An anonymous drawing from the 1860s.

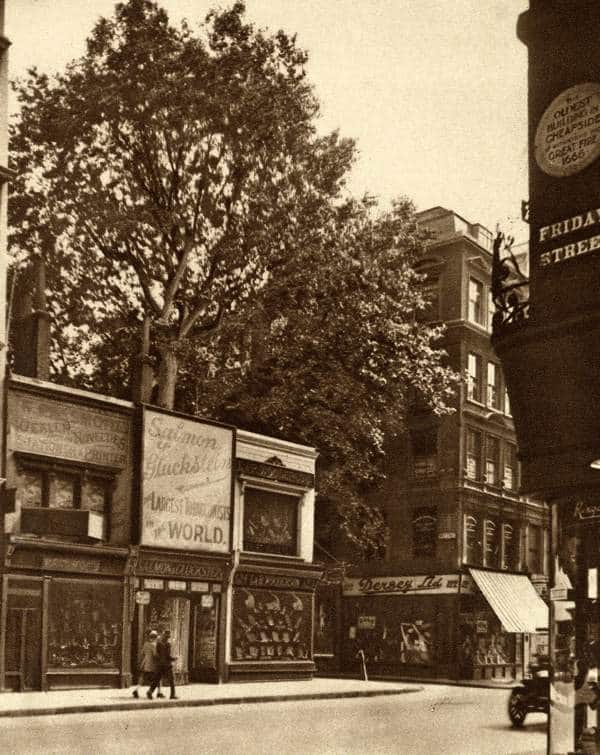

The 1920s – From ‘Spitalfields Life’ – pictures selected from the three volumes of ‘Wonderful London’ edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties.

As I remember it in the 1970s through to the late 1990s. Sadly the lovely glass door engraved with the words ‘L R Woderson under the Tree’ has disappeared and been replaced with plain glass and a security grille.

The rebuilding of the City after the Great Fire took over forty years, but the little shop on Cheapside, along with its three neighbours to the west, were some of the earliest new structures to be built as the City recovered. The site is small and each of the shops in the row consists of a single storey above and a box front below. According to Peter Ackroyd, in his London, the Biography, many trades have operated there since the stores were built in 1687. These included silver-sellers, wig-makers, law stationers, pickle- and sauce-sellers, fruiterers, florists and, as can be seen above, shirt-makers. The shop now sells greetings cards.

The little garden at the back of the shop used to be the churchyard of St Peter Westcheap (also known as St Peter Cheap) which was destroyed in the Great Fire and not rebuilt. Three gravestones survive as do the railings which date from 1712.

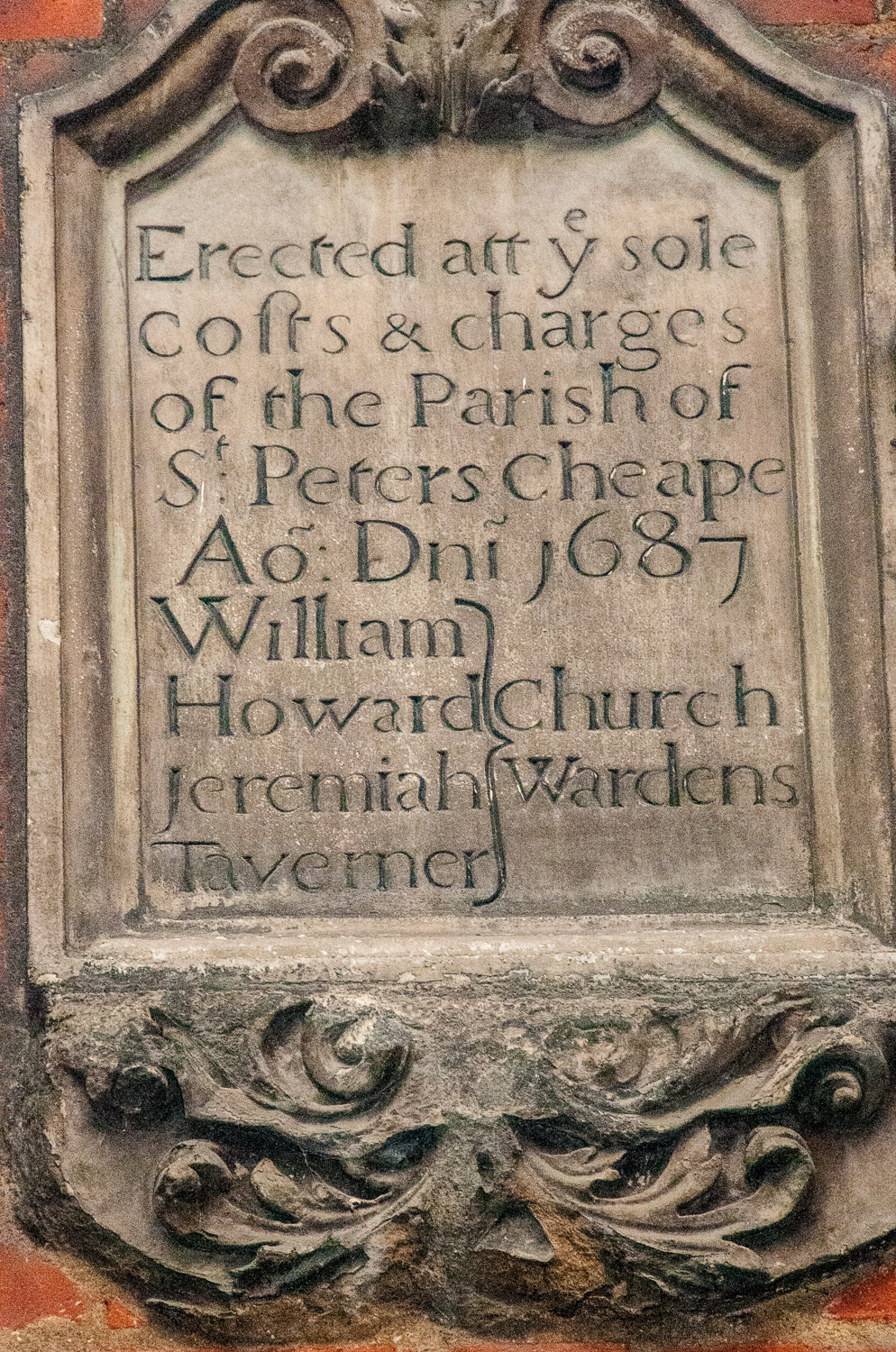

The railings and the names of the Churchwardens who probably raised the money for them.

The railings incorporate an image of St Peter. In his lap and above his head are the Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven.

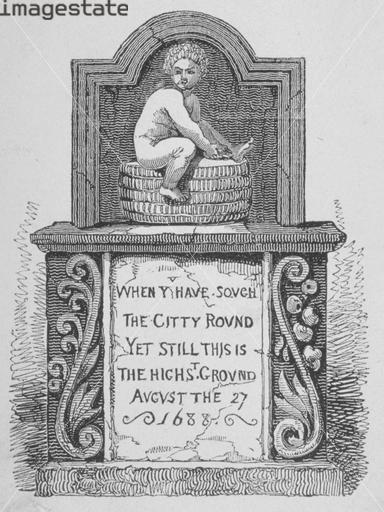

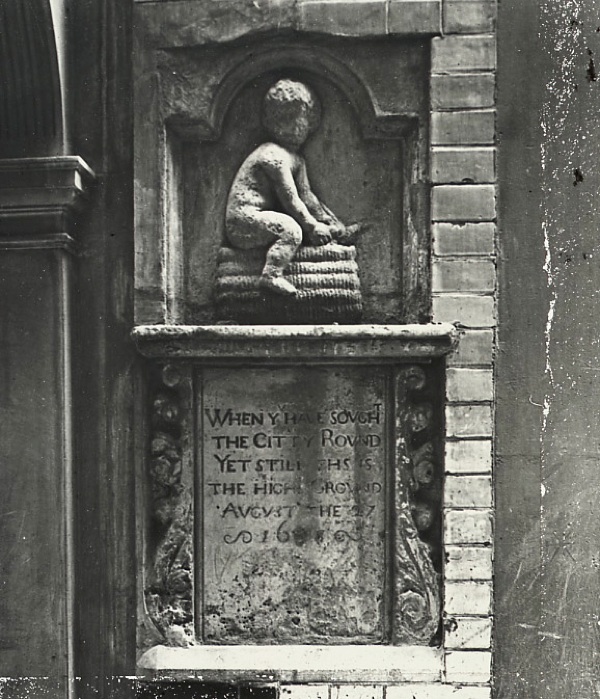

The plaque in the churchyard attached to the Cheapside shop’s northern wall confirms the age of the building …

And finally to the magnificent London Plane tree that you can see in most of the pictures. It stands 70 feet high and is protected by a City ordinance which also limits the height of the shops.

No one knows precisely how old it is but what we do know is that it was there in 1797 when its presence inspired the poet Wordsworth to compose a poem ‘where the natural world breaks through Cheapside in visionary splendour’. The poem, The Reverie of Poor Susan, records the awakened childhood memories of a country girl now working in London, possibly as a servant. I think it is rather sad. An excerpt is displayed in the churchyard, but here is the complete version:

At the corner of Wood-Street, when day-light appears,

There’s a Thrush that sings loud, it has sung for three years.

Poor Susan has pass’d by the spot and has heard

In the silence of morning the song of the bird.‘Tis a note of enchantment; what ails her? She sees

A mountain ascending, a vision of trees;

Bright volumes of vapour through Lothbury glide,

And a river flows on through the vale of Cheapside.Green pastures she views in the midst of the dale,

Down which she so often has tripp’d with her pail,

And a single small cottage, a nest like a dove’s,

The only one dwelling on earth that she loves.She looks, and her heart is in Heaven, but they fade,

The mist and the river, the hill and the shade;

The stream will not flow, and the hill will not rise,

And the colours have all pass’d away from her eyes.

As Ackroyd declares, in his unique, poetic style …

Everything about this corner of Wood Street suggests continuity … on every level, human, social, natural and communal.

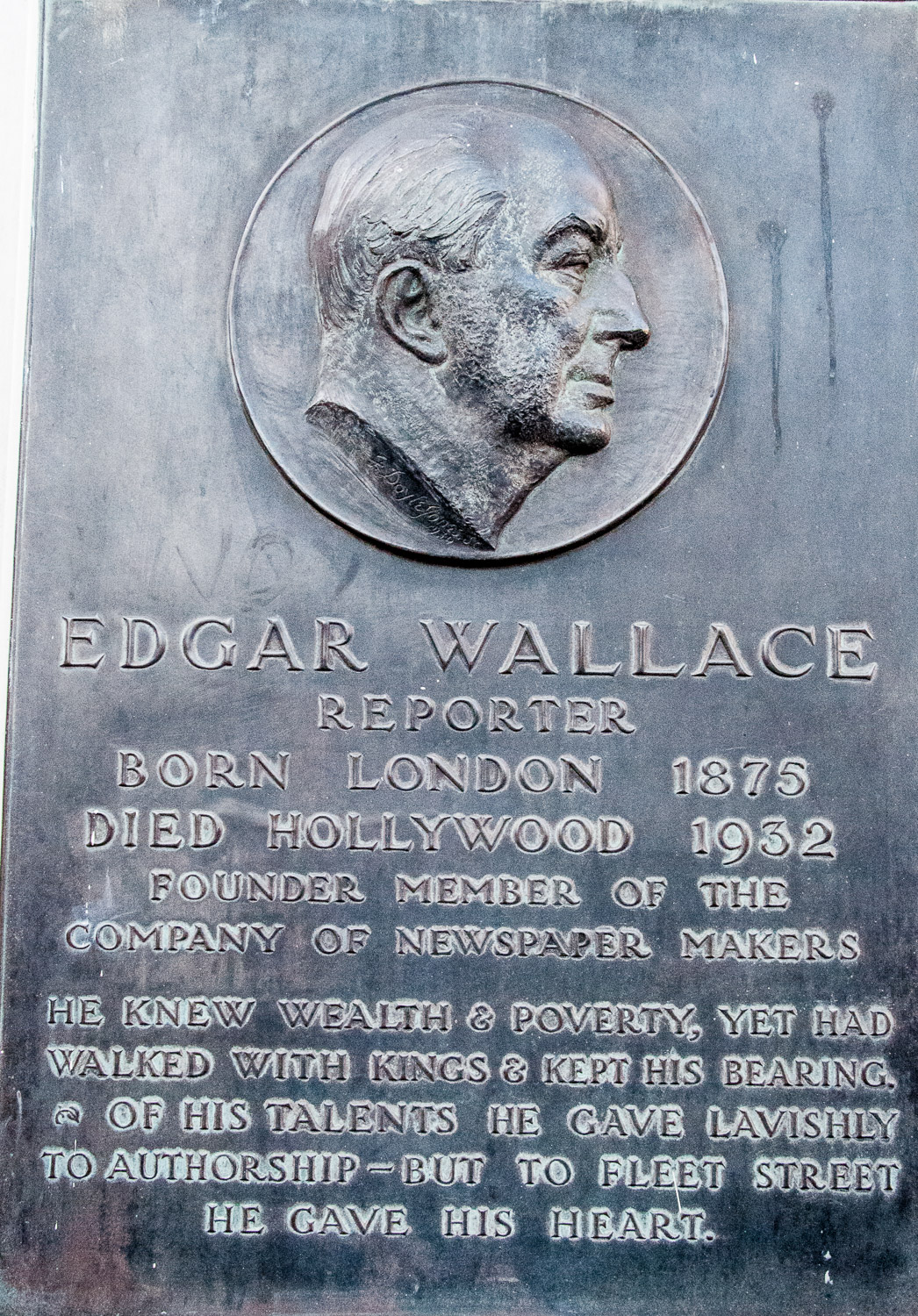

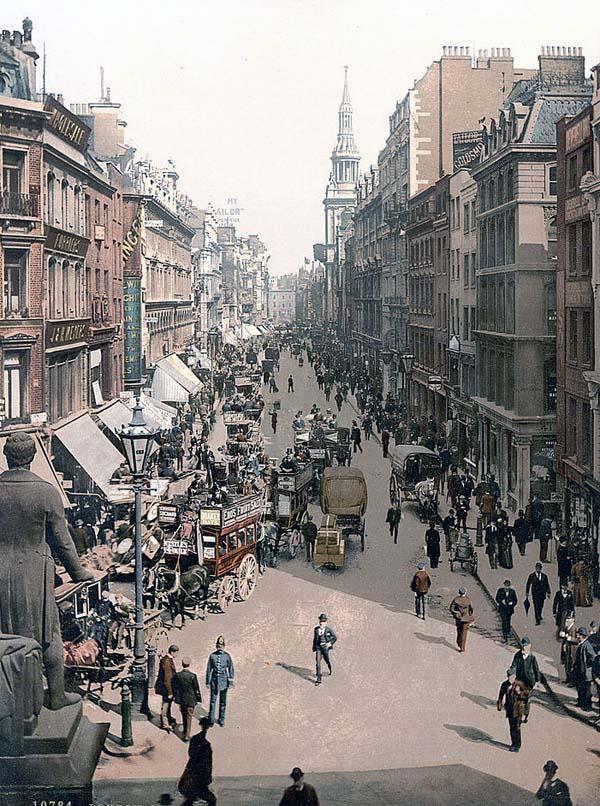

I thought this picture was worth including. Sir Robert Peel looks east down Cheapside around the turn of the 20th century (and a uniformed ‘Peeler’ stands beneath the lamp post). The shops gradually disappeared for a while as commerce took over but now they are back in abundance, especially with the new development at New Change.

Sir Robert was moved in 1933 to reduce traffic congestion. He is now outside the Peel Centre in Barnet (more familiarly known as Hendon Police College).