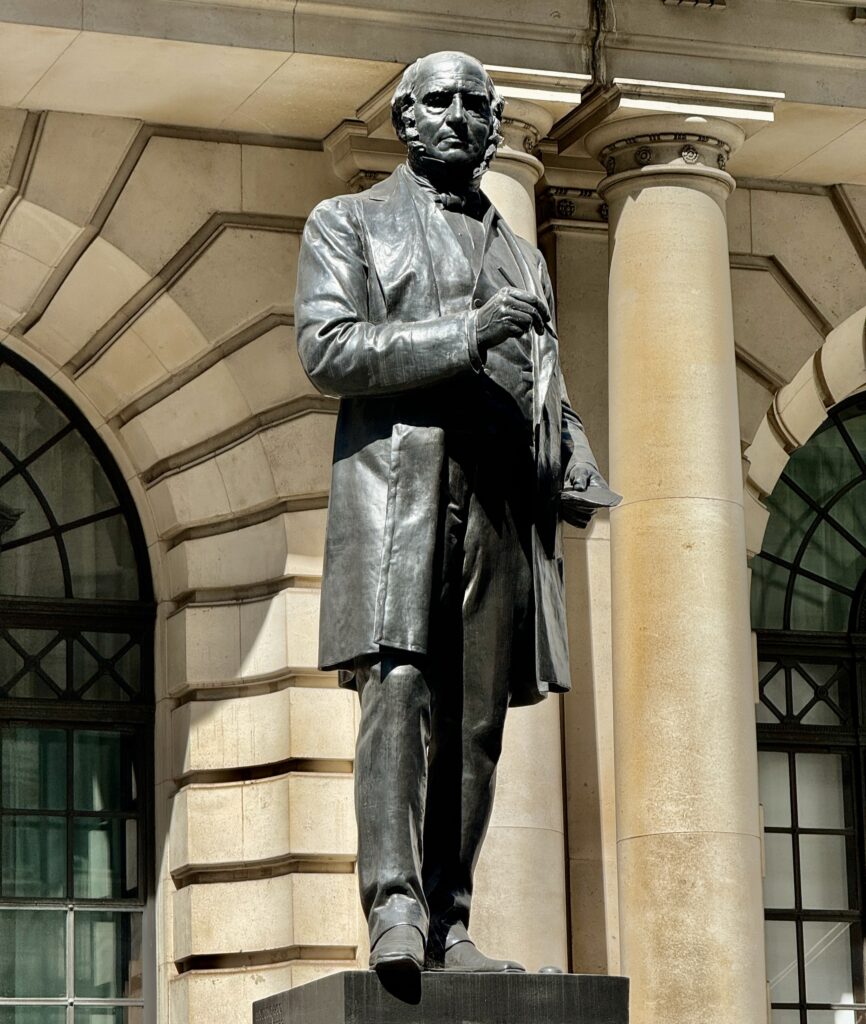

St Michael Cornhill impresses even before you go through the door.

Above the entrance is the warrior Archangel Michael ‘disputing with Satan’. It was carved by John Birnie Philip when the church was remodelled in 1858-1860. No question as to who is winning this battle …

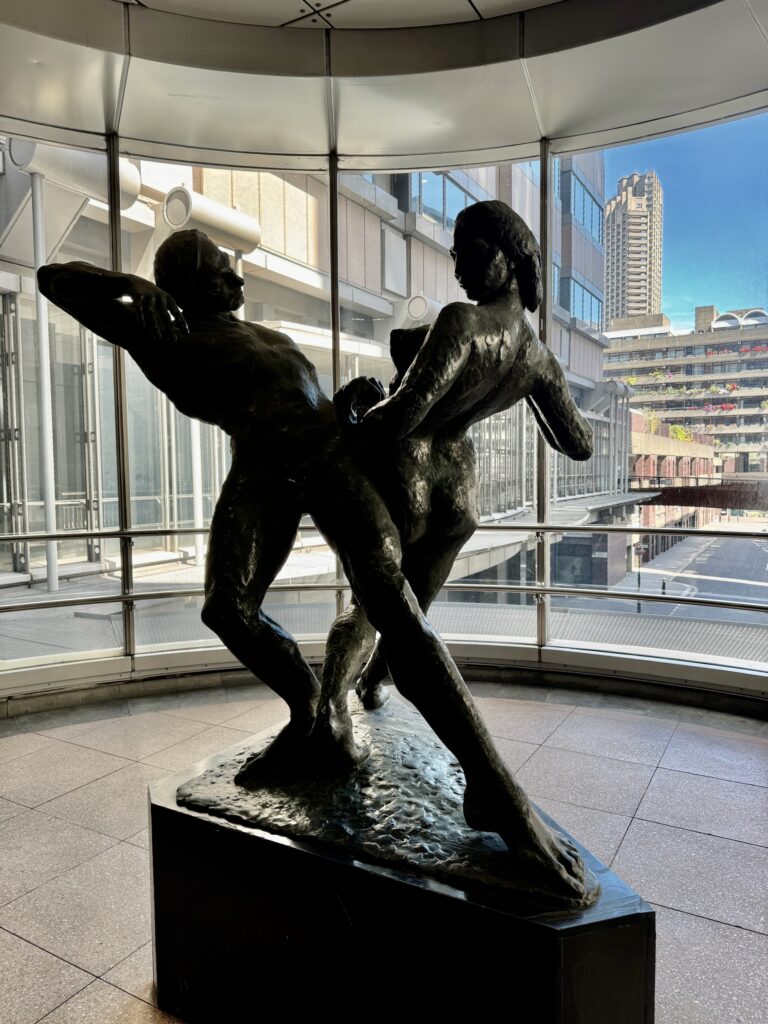

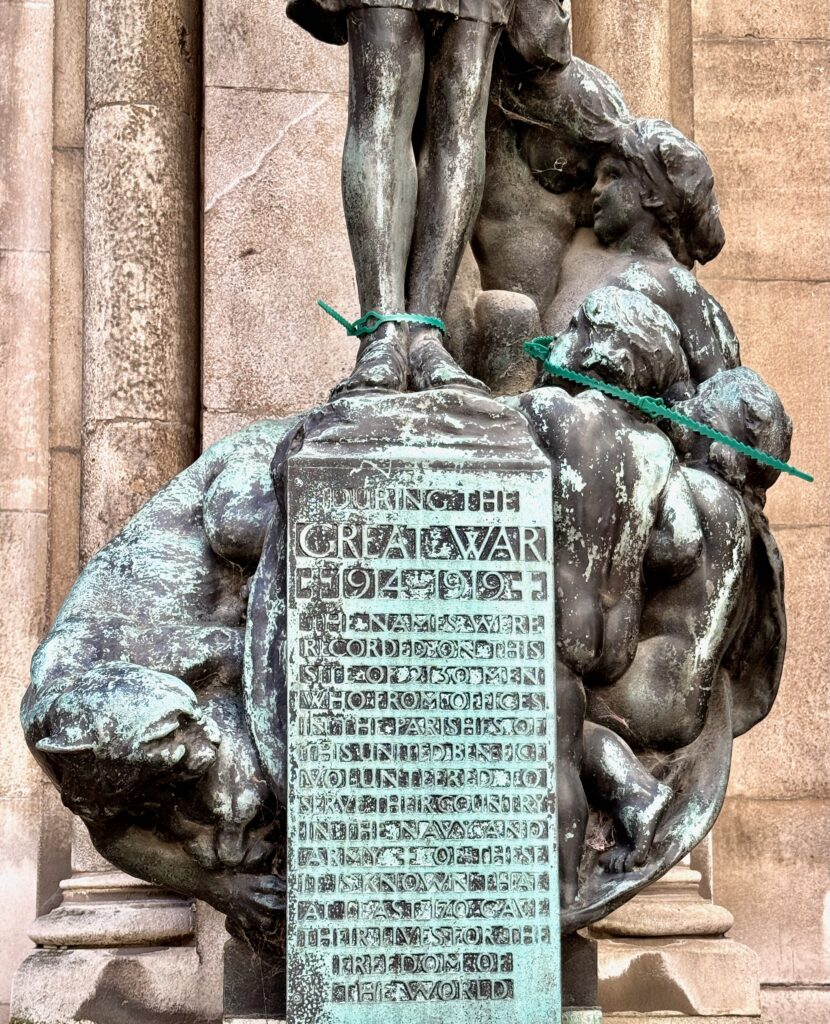

To the right of the entrance is another sculpture of Michael brandishing a flaming sword. It is a bronze memorial to the 170 out of the 2,130 men of this parish who enrolled for military service in the First World War and died as a result …

The sculpture (by R R Goulden) was described in the Builder magazine as follows

St Michael with the flaming sword stands steadfast above the quarreling beasts which typify war, and are sliding slowly, but surely, from their previous paramount position. Life, in the shape of young children, rises with increasing confidence under the protection of the champion of right.

Walk down the narrow alley beside the church and you come to a lovely, quiet churchyard where you get a good view of the commanding tower …

Originally believed to be by Wren, it was rebuilt in the ‘Gothic’ style between 1718 and 1722 by his protégé Nicholas Hawksmoor.

The church, with the exception of the tower, was completely destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. The church history notes state that it was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren between 1669 and 1672. The interior, with its majestic Tuscan columns, was beautified and repaired in 1701 and again in 1790 and then extensively ‘remodelled’ in the High Victorian manner by Sir George Gilbert Scott between 1857 and 1860 …

John Birnie Philip also carved the angels …

Pre-Victorian features that remain today include 17th century paintings of Moses and Aaron incorporated into the reredos …

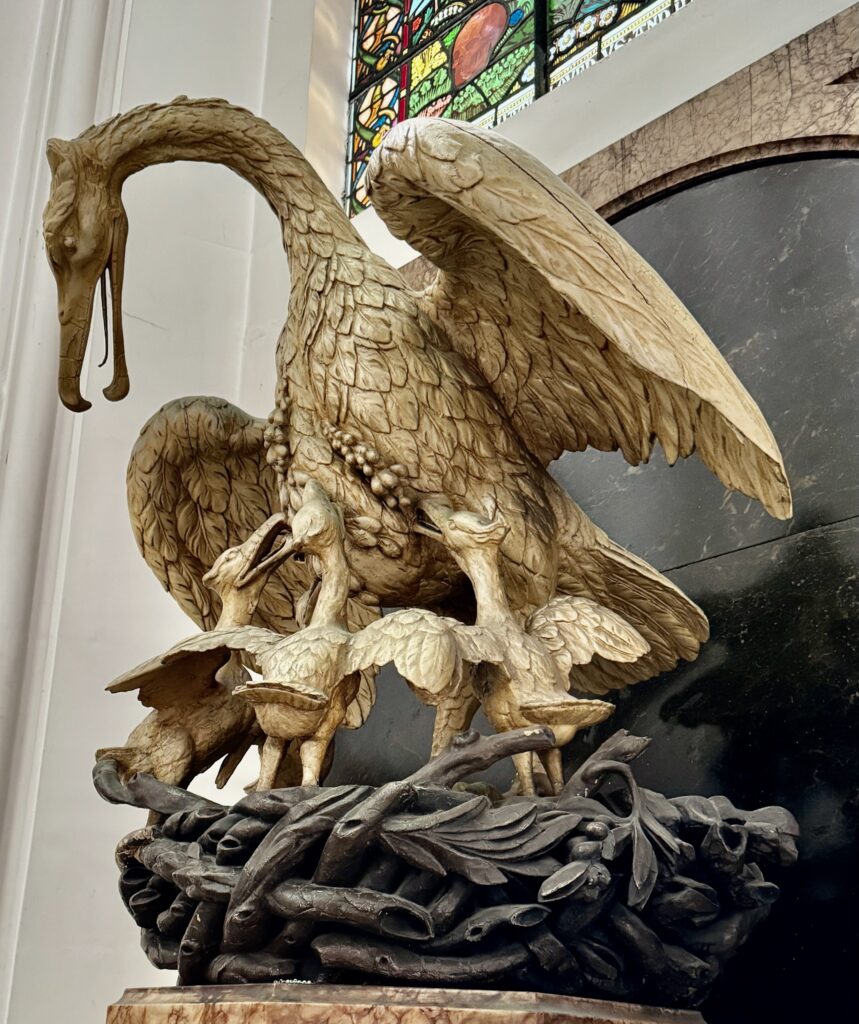

… and a beautiful wooden sculpture of ‘Pelican in her Piety’ dating from 1775 …

The 1850s stained glass was made by the firm Clayton & Bell …

The box pews date from the Scott remodelling …

In 1716, the poet Thomas Gray, famous for his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, was born in a milliner’s shop adjacent to St. Michael’s and was baptised in the church. Two hundred years later, Martin Neary, who became Master of the Music at Westminster Abbey, was baptised in the same font, which dates from 1672 …

Look to the left on entering and you’ll see the noteworthy Churchwarden’s pew …

It shows St Michael thrusting a lance into the mouth of a truly evil-looking devil. It’s a work by the eminent wood carver William Gibbs Rogers (1792-1875) …

The present organ began life in 1684 …

You can read more about its fascinating history here. I attended the recital last Monday. Absolutely wonderful. On Bank Holiday Monday (26 August) at 1:00 pm you can listen online as David Goode plays Holst’s The Planets. Join on Zoom from 12:45 pm ID 828 1357 0952 Passcode 827123.

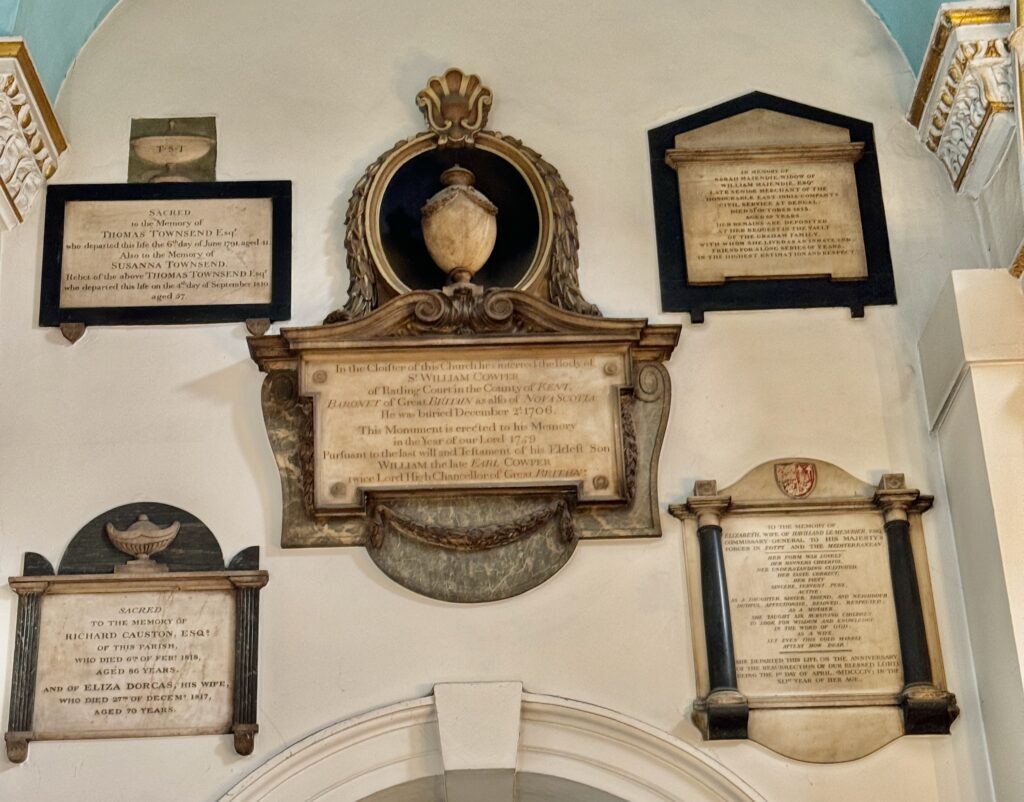

Regular readers will know that I like a nice monument or memorial and this church has over 40 of them, many in clusters like these …

I’ve picked a few favourites.

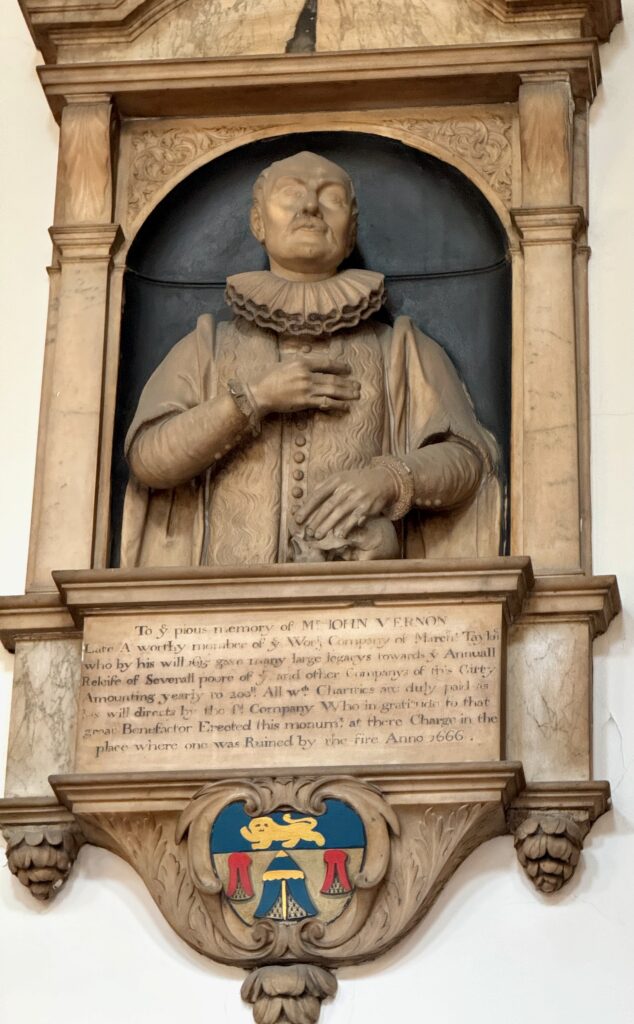

The earliest is to John Vernon who died in 1615. It was erected by the Merchant Taylors Company after the Great Fire of 1666 to replace the ‘ruined’ original. He was a generous benefactor to the Company and its scholars. When he started to lose his sight he gifted his collection of paintings to the company so his fellows could better enjoy them as he could no longer see. Every year at Christmas boys from the Merchant Taylors’ School visit the church to sing at the special Vernon Carol Service …

He has a contemplative expression enhanced by the posing of his hands, one to his breast, the other resting on a skull, emblem of mortality and death. He wears a broad ruff and a fur lined cloak.

Next door, the Platt Family cherub endeavours to keep his feet warm …

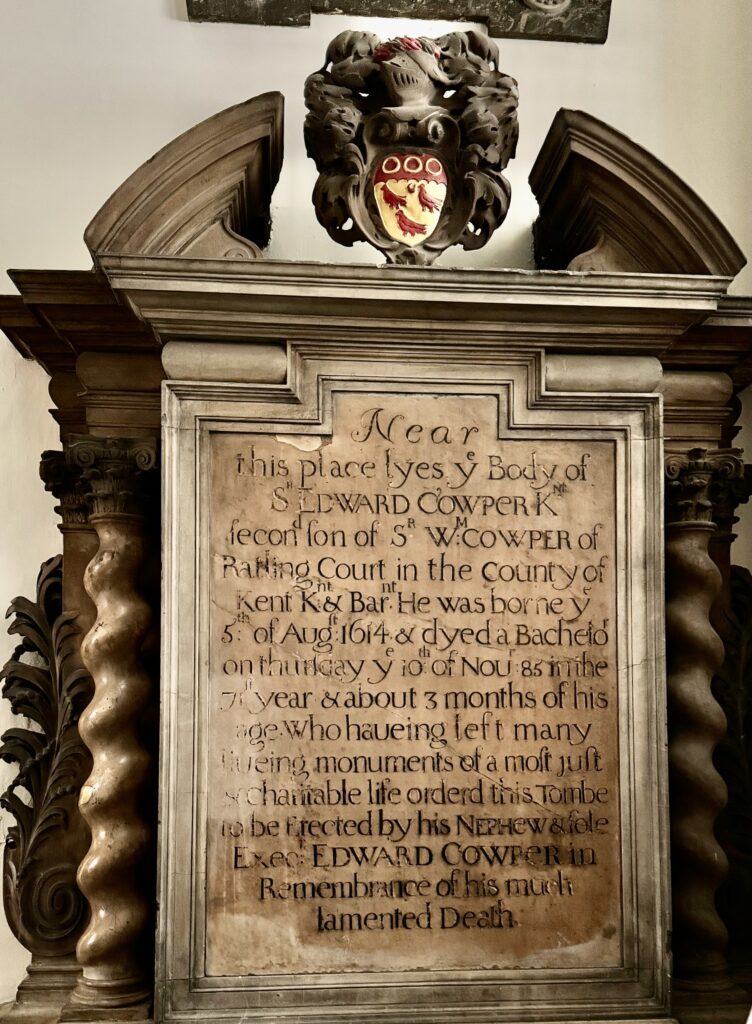

The biggest monument in the Church is to Sir Edward Cowper who died in 1685. Bob Speel describes it as follows: ‘a grand mass of marble rising from the floor with fantastically twisted pillars and strikingly coloured marble. Perhaps by the sculptor Thomas Cartwright Senior, another of the sculptor-masons working on Wren’s City Churches’ …

In the same corner of the Church is the monument to Sir William Cowper, who died in 1664 and his wife Martha [Master] of East Langdon, and their fourth son, Spencer Cowper …

If you want to visit and inspect the memorials in more detail let Bob Speel be your guide.

I admired the coats of arms at the end of the pews …

This one in particular intrigued me …

Whose arms are these? The mitre in the carving suggests a bishop but what are the birds all about, with their necks pierced by arrows? All is revealed in the Friends of City Churches Newsletter – highly recommended!

In addition to the war memorial outside there are several inside the church itself.

This one reads: In proud and grateful memory of the men of the County of London Electric Supply Company Limited and its associated companies who gave their lives for their country.

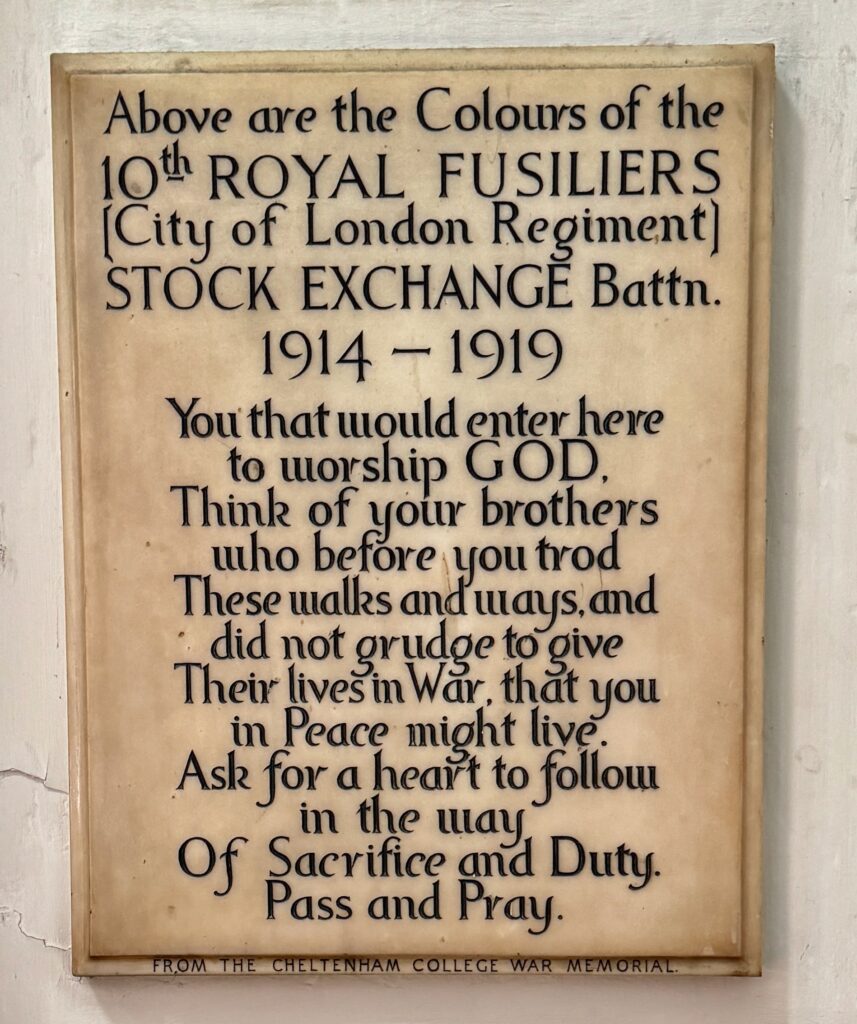

The Royal Fusiliers and local office workers …

The Stock Exchange Battalion …

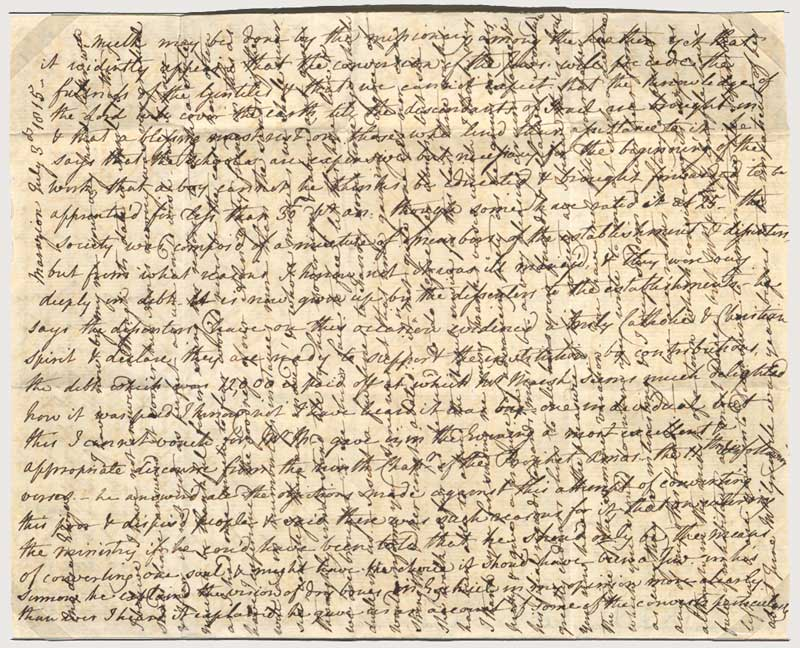

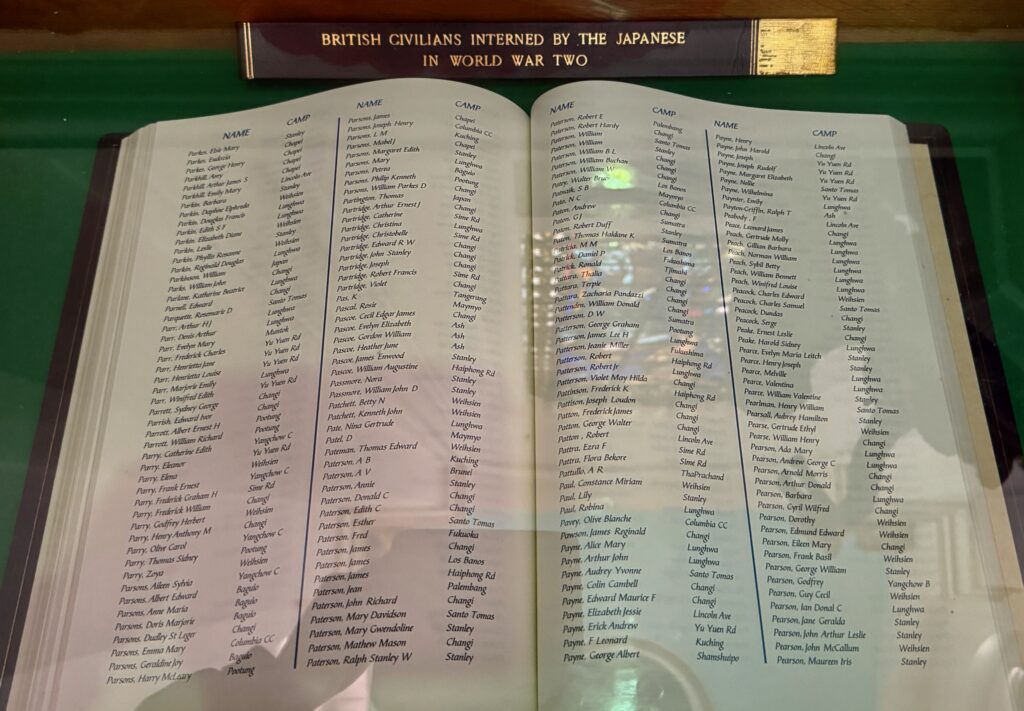

And finally, an unusual item. This is a book prepared by the Association of British Civilian Internees, Far East Region, and placed here on 24th May 2009 …

St Michael’s church doesn’t seem to be open very often (despite what the website says). I got in because I wanted to attend the organ recital. According to their website, the wonderful Friends of City Churches are there on Tuesdays between 11:00 and 3:00.

On my way home this shop window display made me smile…

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …