Did you realise that, just off Cannon Street, is the final resting place of Catrin Glyndwr, daughter of Welsh hero Owain Glyndwr? She was captured in 1409 and taken with her children and mother to the Tower of London during her father’s failed fight for the freedom of Wales. A memorial to her, and the suffering of all women and children in war, was erected in the former churchyard of St Swithen where she was buried. It survives as a raised public garden and here is the pretty entrance gate on Oxford Court (EC4N 8AL) …

And this is the memorial …

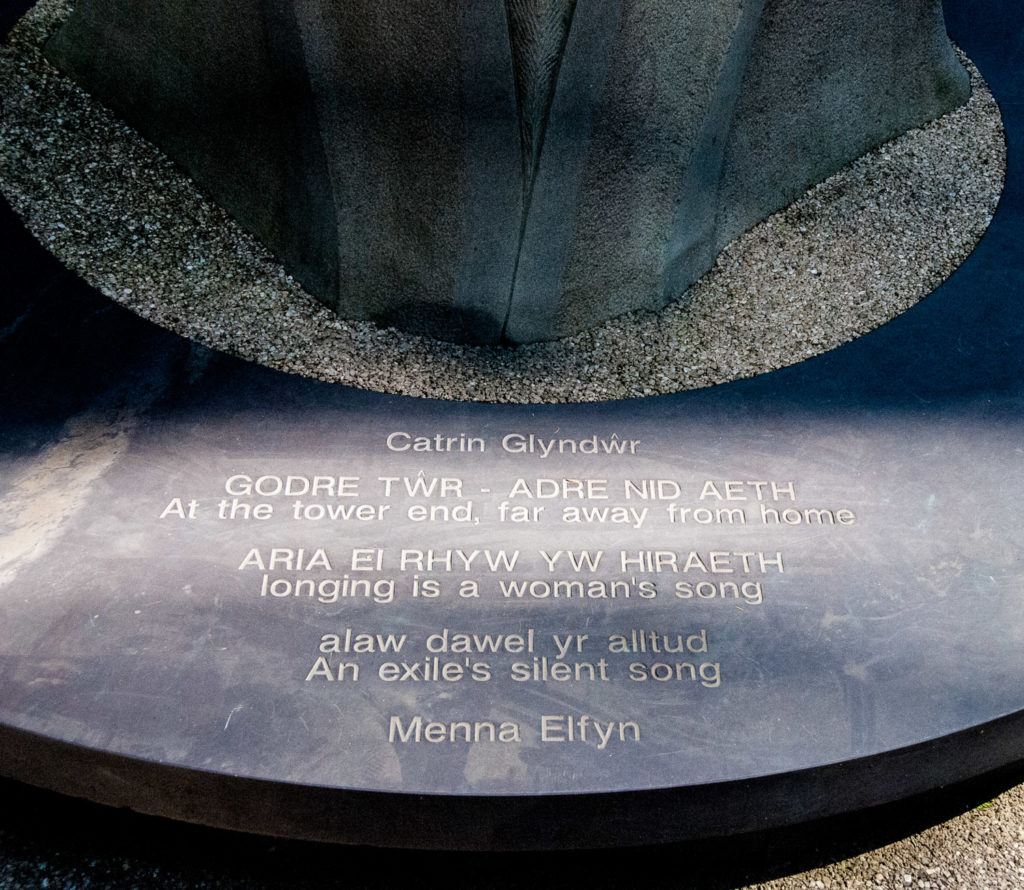

With its inscription …

The garden is a cosy, secluded space with seating where you can enjoy a break from the City hustle and bustle …

The Church itself was demolished as a result of World War II bombing.

St Clement’s Eastcheap isn’t on Eastcheap, for reasons I will go into in a future blog. It’s in the appropriately named St Clement’s Lane (EC4N 7AE). As you look down the Lane from King William Street it’s tucked away on the right …

Just past the church is St Clement’s Court, the narrow alley leading to the churchyard. There is an intriguing plaque on the wall of the adjacent building …

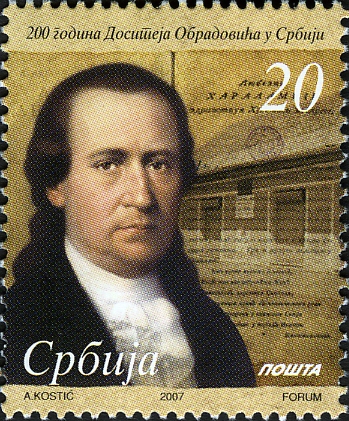

Obradović was a Serbian writer, philosopher, dramatist, librettist, translator, linguist, traveler, polyglot and as the plaque says, the first minister of education of Serbia. Here is a link to his Wikipedia entry. He was honoured in 2007 by a special Serbian stamp …

You enter the churchyard via three steps. City churchyards are frequently higher than street level, evidence of how may bodies were crammed in until graveyards were closed to new burials in the middle of the 19th century …

The churchyard was reduced in size in the 19th century by an extension that was added to the church and all that remains now are a couple of gravestones and two chest tombs …

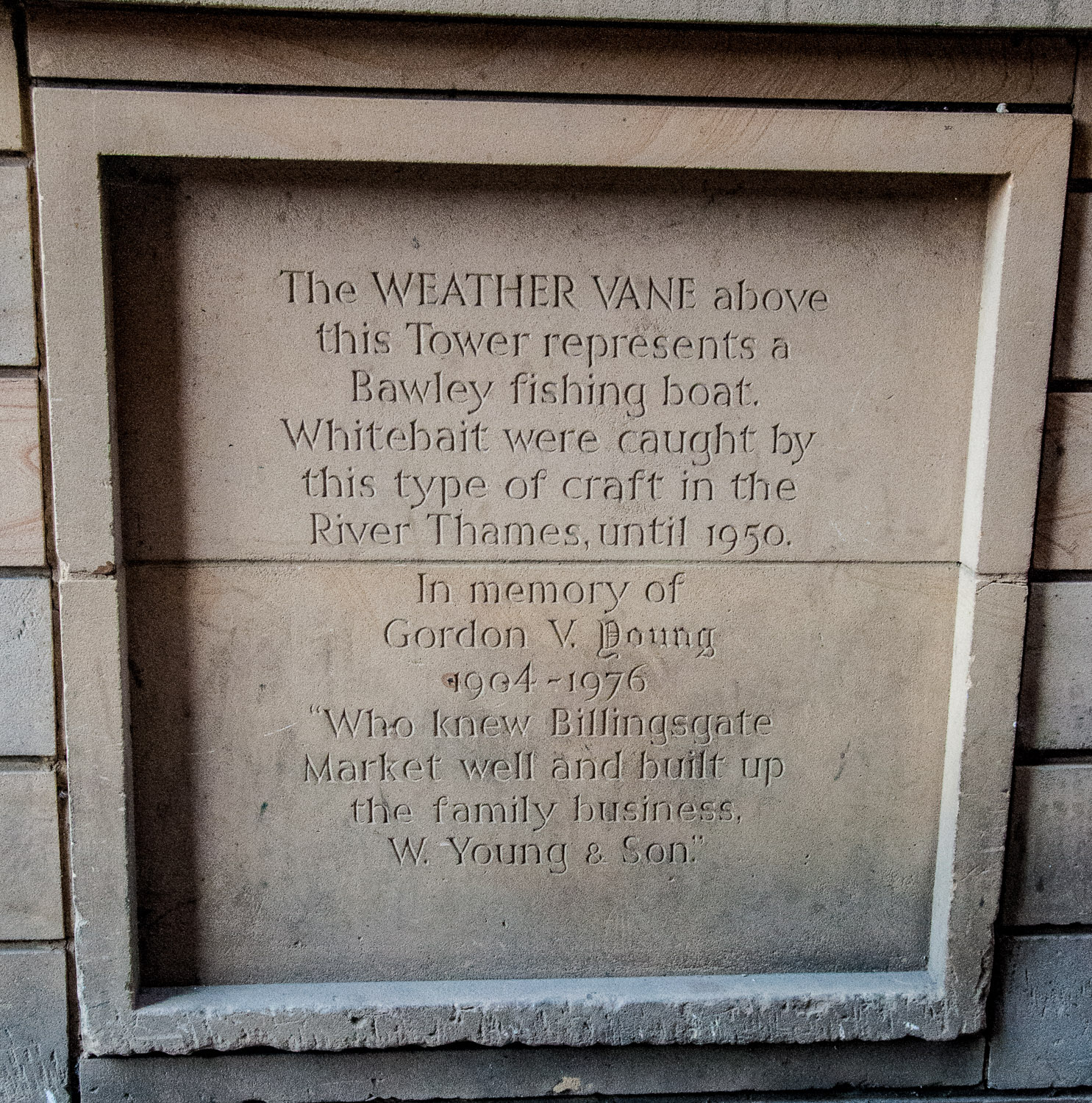

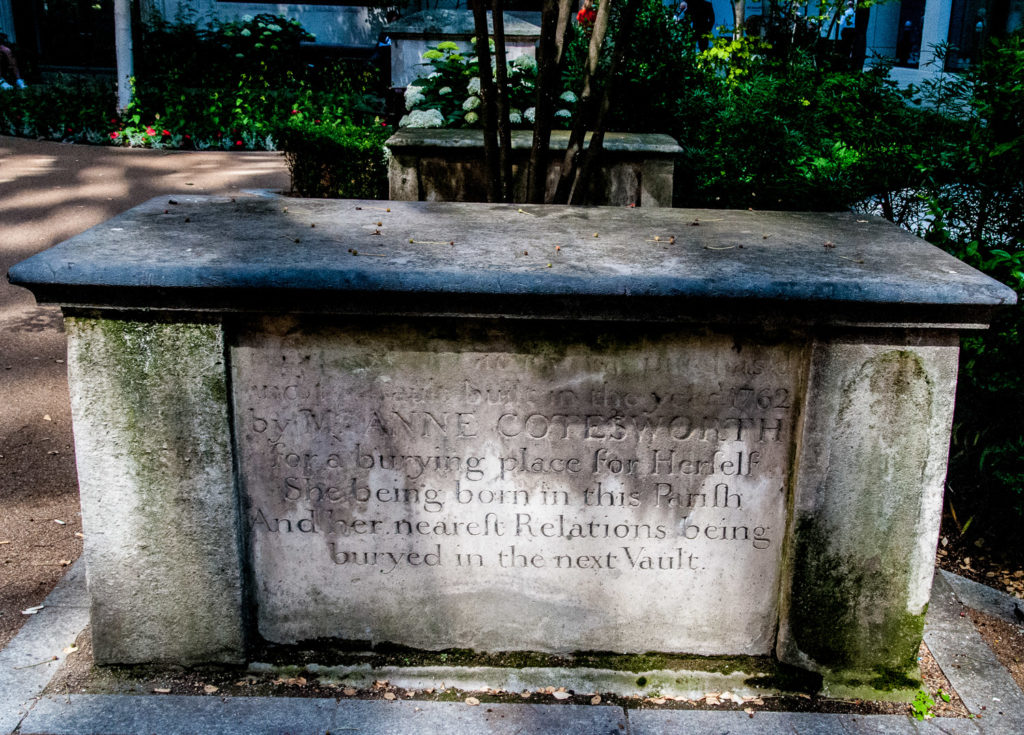

The inscription on one is just about legible, it reads …

In memory of Mr JOHN POYNDER late of this Parish who departed this life on 11th April 1800 aged 48 years. Also four of his children who died in their infancy.

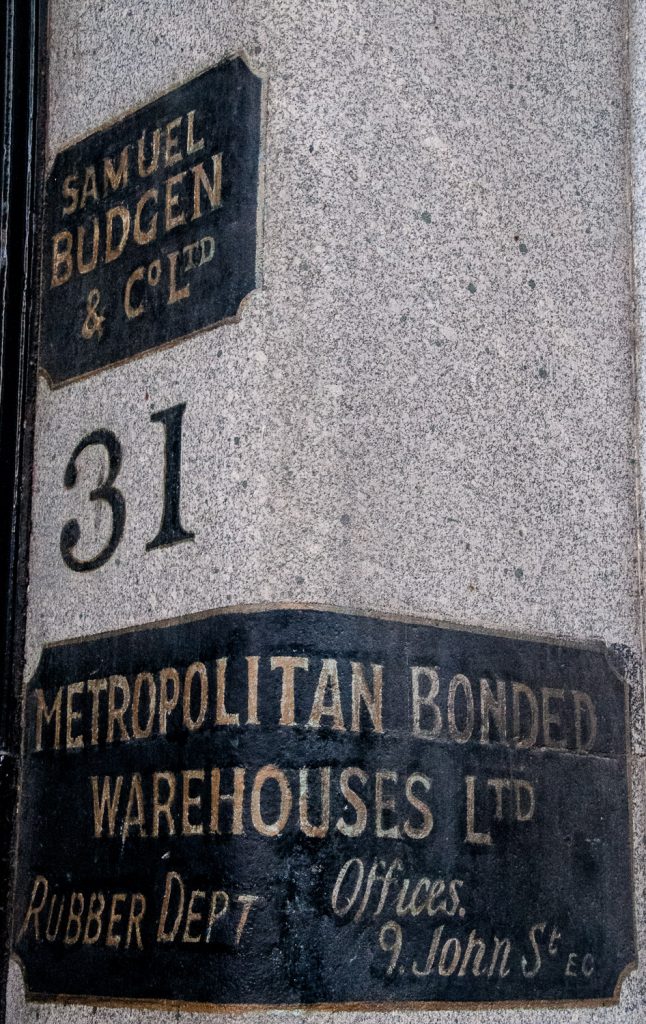

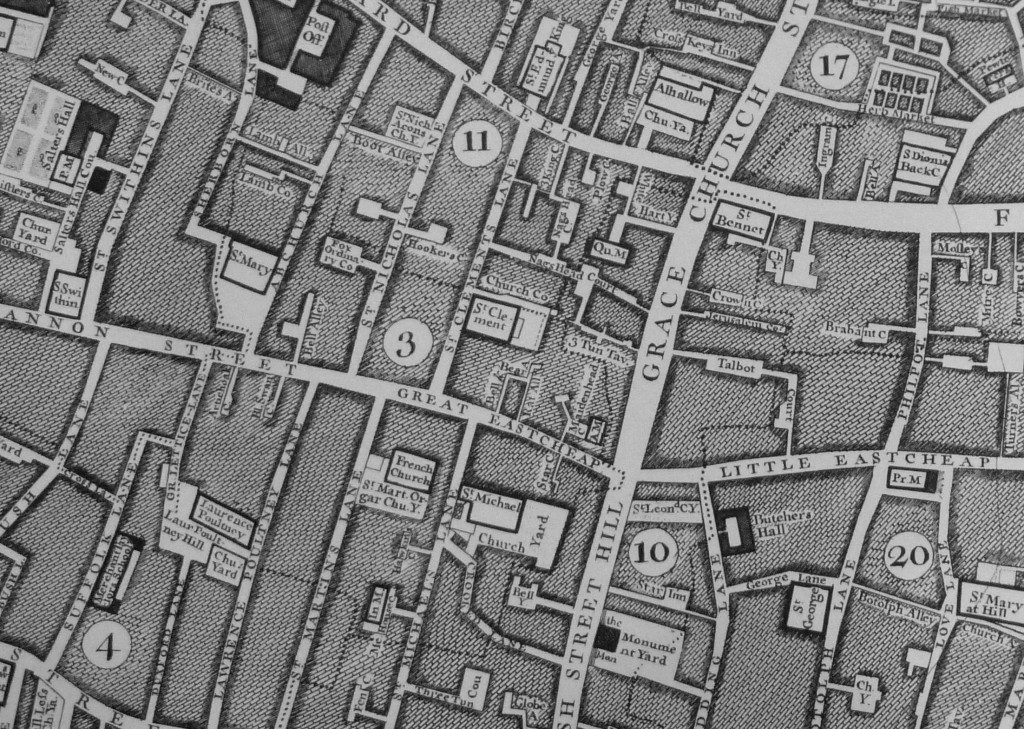

The narrow alleyway can be traced back to 1520 and St Clement’s Lane is also an old thoroughfare. Here it is on Roques map of 1746 leading then, as it does now, to Lombard Street directly opposite the Church of St Edmund King and Martyr …

Here’s another view from King William Street, you can see St Edmund’s in the distance …

The church dates from 1674 having been rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire (although the design was probably by his able assistant Robert Hooke). In 2001 it became the London Centre for Spirituality …

To find the churchyard, now a private garden, head down George Yard adjacent to the church (EC4V 9EA). It closed for burials in 1853 …

One tomb is visible from the street …

It has a fascinating inscription …

Sir HENRY TULSE was a benefactor of the Church of St Dionis Backchurch (formerly adjoining). He was also Grocer, Alderman & Lord Mayor of the City. In his memory this tombstone was restored in 1937 by THE ANCIENT SOCIETY OF COLLEGE YOUTHS during the 300th year of the Society’s foundation. He was also Master of the Society during his Mayoralty 1684.

St Dionis Backchurch was demolished in 1878 and the proceeds of the land sale used to resurrect it as a new church of the same name in Parsons Green. The Ancient Society of College Youths is the premier change ringing society in the City of London, with a national and international membership that promotes excellence in ringing around the world. Sir Henry owned significant estates in South London – you’ll be remembering him as your train trundles through Tulse Hill Station.

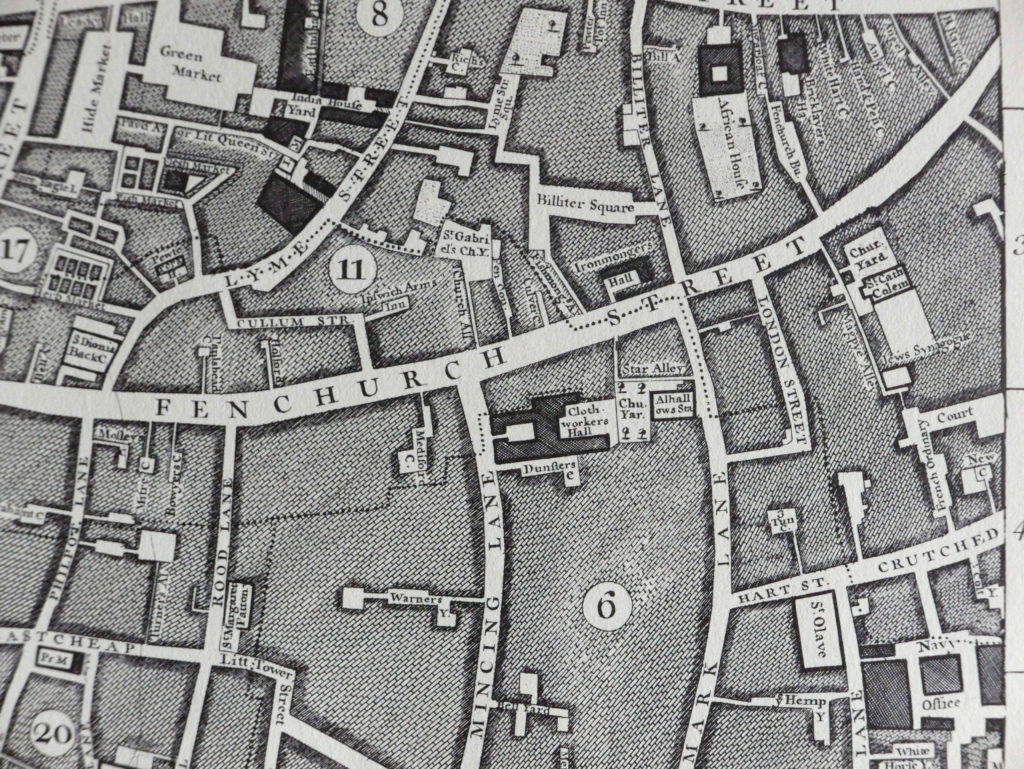

St Gabriel Fenchurch was destroyed in the Great Fire and not rebuilt but its churchyard remains – now called Fen Court (EC3M 6BA) it’s just off Fenchurch Street. If you are feeling stressed, or just need to take time out, you can use the labyrinth there to walk, meditate and practise mindfulness. It was the idea of The London Centre for Spiritual Direction and you can read more about it here.

Three chest tombs are evidence of it’s earlier burial ground function …

This vault was built in the year 1762 by MRS ANNE COTTESWORTH for a burying place for Herself she being born in this Parish And her nearest relations being buryed in the next Vault

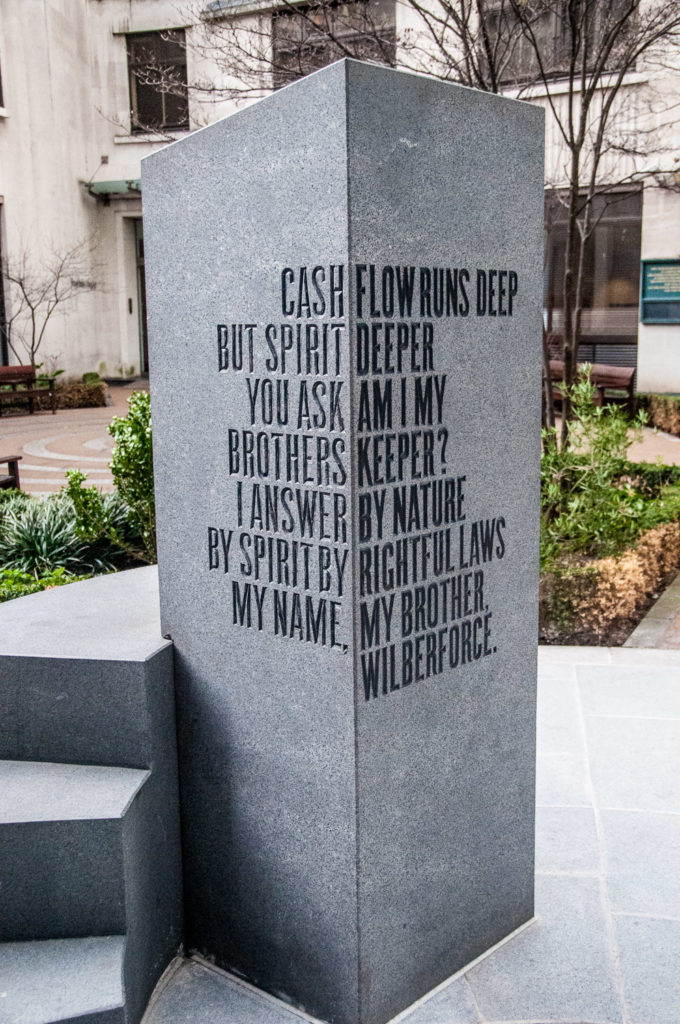

Also there is the striking Gilt of Cain monument, unveiled by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 2008, which commemorates the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807. Fen Court is now in the Parish of St Edmund the King and St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard St, the latter having a strong historical connection with the abolitionist movement of the 18th and 19th centuries. The Rev John Newton, a slave-trader turned preacher and abolitionist, was rector of St Mary Woolnoth from 1780 to 1807 and I have written about him in an earlier blog St Mary Woolnoth – a lucky survivor.

The granite sculpture is composed of a group of columns surrounding a podium. The podium calls to mind an ecclesiastical pulpit or slave auctioneer’s stance, whilst the columns evoke stems of sugar cane and are positioned to suggest an anonymous crowd. This could be a congregation gathered to listen to a speaker or slaves waiting to be auctioned.

The artwork is the result of a collaboration between sculptor Michael Visocchi and poet Lemn Sissay. Extracts from Lemn Sissay’s poem, Gilt of Cain, are engraved into the granite. The poem skilfully weaves the coded language of the City’s stock exchange trading floor with biblical Old Testament references.

And finally here is another meditation labyrinth …

It’s in one of my favourite places, St Olave Hart Street churchyard in Seething Lane (EC3R 7NB) …

You walk in through the gateway topped with gruesome skulls, two of which are impaled on spikes …

It leads to the secluded, tranquil garden …

This was Samuel Pepys’s local church. He is a hero of mine and I have devoted an earlier blog to him and this church : Samuel Pepys and his ‘own church‘.

In 1655 when he was 22 he had married Elizabeth Michel shortly before her fifteenth birthday. Although he had many affairs (scrupulously recorded in his coded diary) he was left distraught by her death from typhoid fever at the age of 29 in November 1669.

Do go into the church and find the lovely marble monument Pepys commissioned in her memory. High up on the North wall, she gazes directly at Pepys’ memorial portrait bust, their eyes meeting eternally across the nave where they are both buried. When he died in 1703, despite other long-term relationships, his express wish was to be buried next to her.

Take a close look at her sculpture – I am sure it is intended to look like she is animatedly in the middle of a conversation …

As you leave the church, notice how much higher the churchyard ground level is …

It’s a reminder that it is still bloated with the bodies of plague victims, and gardeners still turn up bone fragments. Three hundred and sixty five were buried there including Mary Ramsay, who was widely blamed for bringing the disease to London. We know the number because their names were marked with a ‘p’ in the parish register.

Sorry not to end on a more cheerful note! I have written before about City churchyards and you can find the blog here.