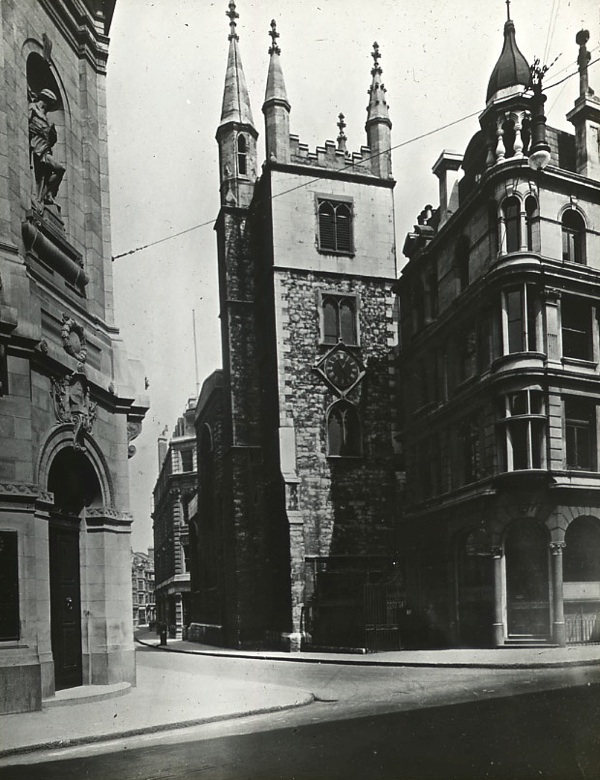

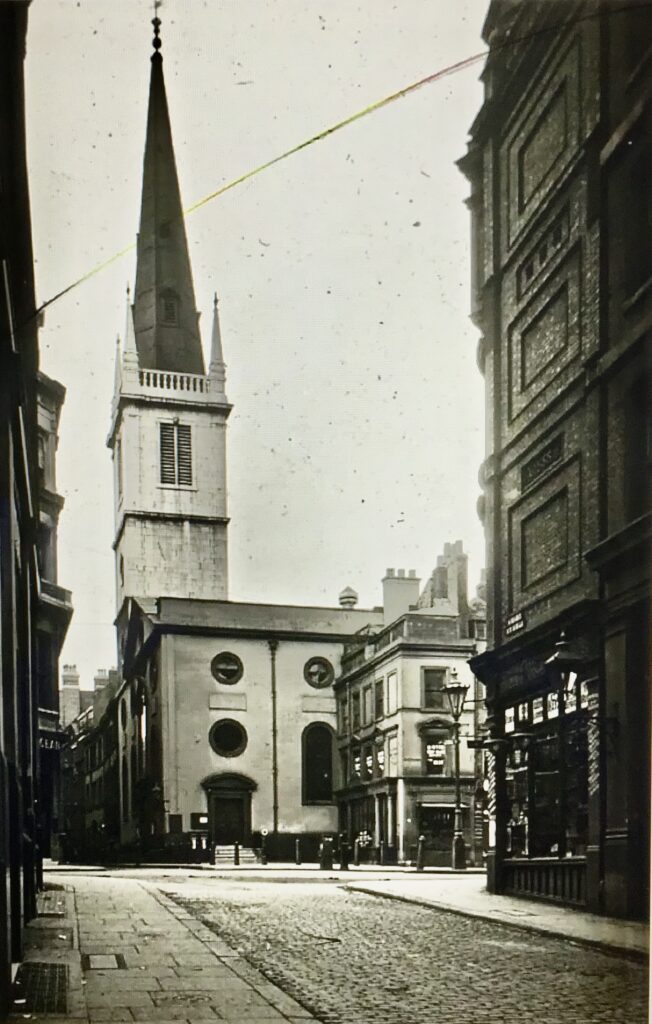

The black and white pictures in today’s blog are old glass slides and were taken for the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society. They are held at the Bishopsgate Institute.

First up is St Mary-le-Bow, built by Christopher Wren between 1670 and 1680 after its predecessor was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. It was gutted in the Second World War bombing (all that remained was the bell tower and the walls) but was rebuilt between 1956 and 1964. Incidentally, the church’s predecessor witnessed other dramas, apart from the catastrophic Great Fire.

In 1091 the roof blew off and in 1271 the steeple collapsed, in each case killing several parishioners. In 1284 Lawrence Duckett, an alleged murderer, sought sanctuary in the church, but a mob burst in and lynched him. In punishment for this act of sacrilege, sixteen men were hanged, drawn and quartered and one woman was burned at the stake. In 1331 a balcony collapsed during a jousting tournament casting Queen Philippa and her attendants into the street. Wren placed an iron balcony on the tower to celebrate the event. Next time you walk down Cheapside think of jousting horses galloping past and the rattle of knights’ armour.

Here’s the church in 1910 …

And the present day …

St Andrew Undershaft was so called because the maypole alongside it was taller than the church. The pole was set up opposite the church every year until Mayday 1517 when the tradition was suspended after the City apprentices (always a volatile bunch) rioted against foreign workers. Public gatherings on Mayday were therefore to be discouraged and the pole was hung up nearby in the appropriately named Shaft Alley. In 1549 the vicar of St Catharine Cree denounced the maypole as a pagan symbol and got his listeners so agitated they pulled the pole from its moorings, cut it up and burned it.

Here is a picture of the church around 1910 …

The view today, literally in the shadow of the Gherkin …

St Margaret Pattens is another Wren church, completed in 1702. The dedication is to St Margaret of Antioch and ‘pattens’ refers to wooden clog-like footwear which, strapped to the feet of medieval Londoners, enabled them to wade through the debris of the City with minimal damage to their shoes. The artisans who made them worked nearby in Rood Lane and a pair of pattens were on display at the Museum of London Secret Rivers exhibition in 2019 …

Here’s the church in 1920 …

And today …

St Mary Woolnoth is the only remaining complete City church by Wren’s gifted assistant, Nicholas Hawksmoor. It is also the only City church to have survived the Second World War unscathed. Built between 1716 and 1727 its exterior, with its flat topped turrets, is often regarded as being the most original in the City. Definitely worth visiting if only to see the memorial to the reformed slave trader John Newton whose preaching (from the pulpit still in the church) inspired William Wilberforce. You can read more about him and the church here.

This picture was taken around 1920 …

And here’s how it looks today …

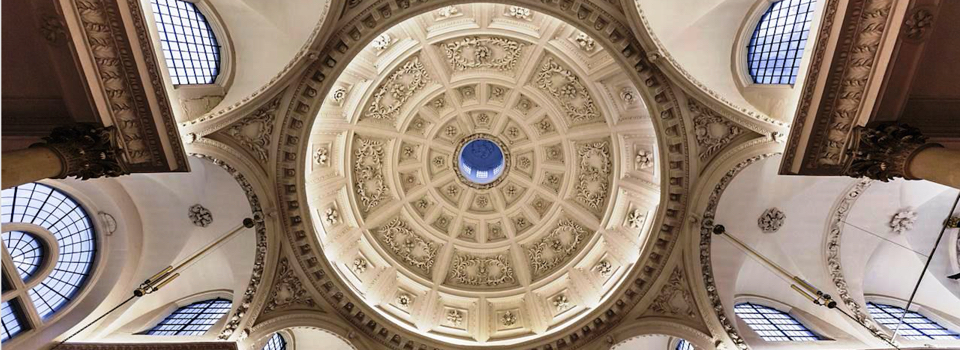

St Stephen Walbrook was rebuilt by Wren in 1672-80 and was one of his earliest and largest City churches. The pains taken with the church are perhaps partly explained by the fact that he used to live next door. The beautiful dome was one of the first of its kind in any English church – a forerunner of Wren’s work on St Paul’s Cathedral. It is not known whether the wonderfully named Mr Pollixifen, who lived beside the church, was placated by the beauty of the building having, during its construction, complained bitterly that it was obstructing the light to his property. You can read more about what can be found inside the church here.

In 1917, when this picture was taken, a bookshop abutted the building …

The same view today from outside the Mansion House …

The dome – a Wren masterpiece …

St Alban Wood street was dedicated to the first English martyr who died in the fourth century. By the 17th century the original medieval church was in a very poor state of repair and was demolished and rebuilt in 1634 only to be destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. Christopher Wren undertook its second rebuilding which was completed in 1685.

The church was restored in 1858-9 by George Gilbert Scott, who added an apse, and the tower pinnacles were added in the 1890s. It was destroyed on a terrible night, 29 December 1940, when the bombing also claimed another eighteen churches and a number of livery halls. Some of St Alban’s walls survived but they were demolished in 1954 and now nothing remains apart from the tower – not even a little garden to give it some cover from the traffic passing on both sides. I’ve often been told someone lives there but I have never seen any evidence of it.

Here’s the church in its Wood Street setting around 1875 …

And in splendid isolation today …

I think that’s probably enough for the time being. I will return to the ‘then and now’ theme in a future blog. I am indebted to the wonderful little book London’s City Churches by Stephen Millar for the source of much of today’s information. Many thanks also to the Spitalfields Life blog for the old pictures – you can see them and more here.

Finally, some ‘reasons to be cheerful’.

The Magnolia is in bloom at St Giles …

And the wonderful City gardeners have continued to work tirelessly to keep the City looking its best …

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …