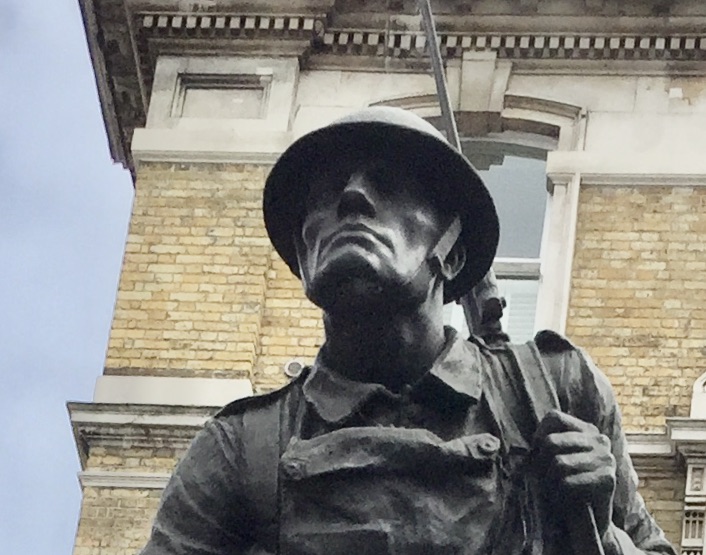

You only need to visit the Watts Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice in Postman’s Park to see evidence of the dangers that people were exposed to in Victorian times.

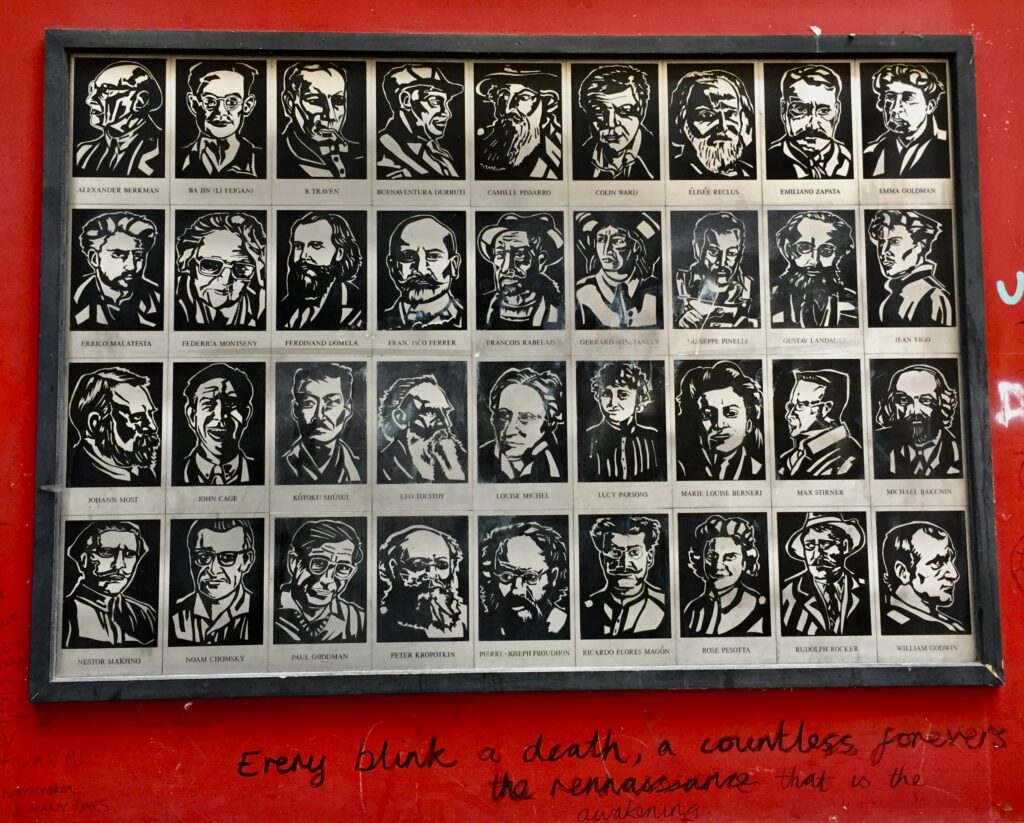

Here is the man we have to thank for this window on the past …

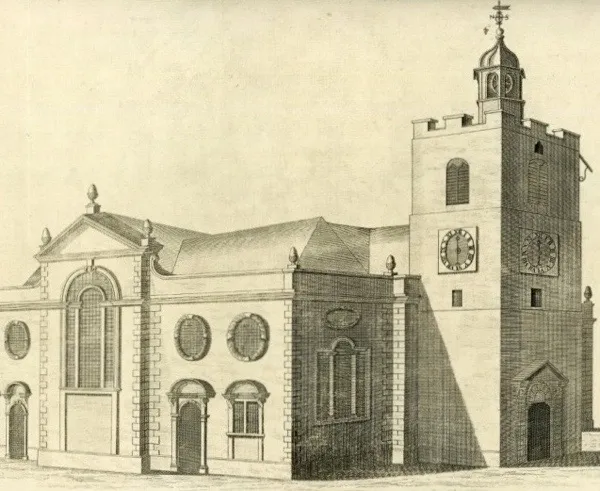

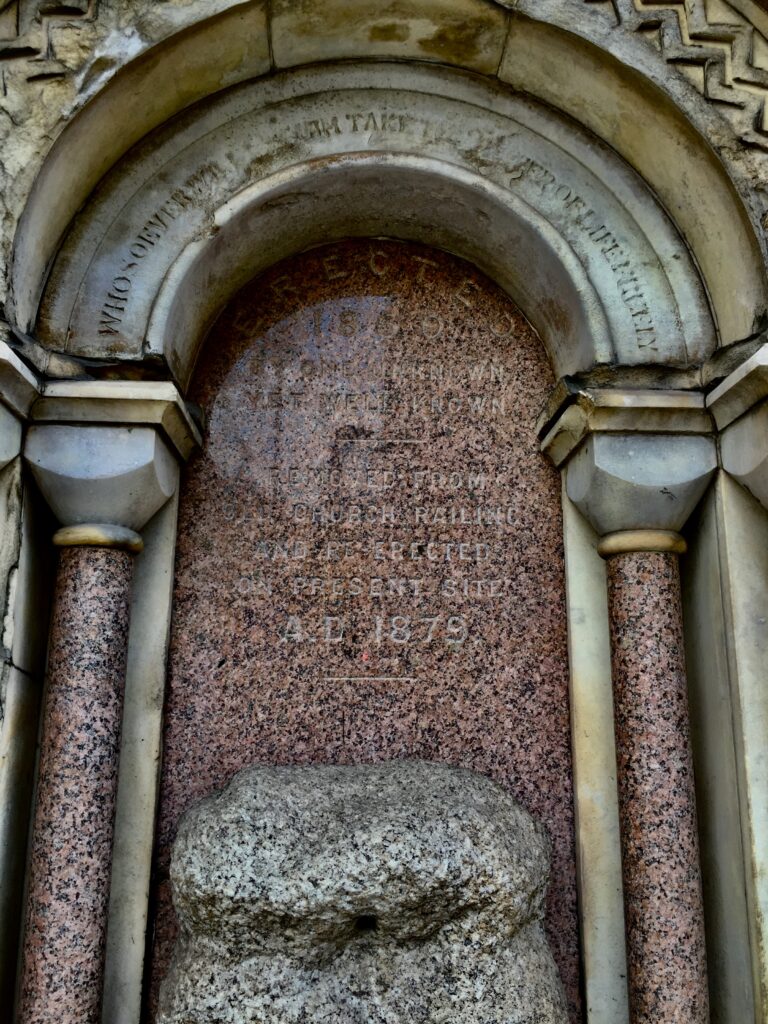

George Frederic Watts was a famous Victorian artist and this picture is a self-portrait. He first suggested the memorials we see today in 1887 but the idea was not taken up until 1898 when the vicar of St Botolph’s church offered him this site in Postman’s Park. There Watts’ ambition to commemorate ‘likely to be forgotten heroes’ came to fruition and when the park was officially opened on 30 July 1900 there were already four tablets in place.

Sixty two people feature on the memorial today which is housed in a wooden loggia …

I find that their stories still evoke a range of emotions, particularly ones of sadness and curiosity, which left me wanting to know more about these people, their lives and the manner of their deaths. There are also clues as to the nature of society and work at that time along with the quality of healthcare.

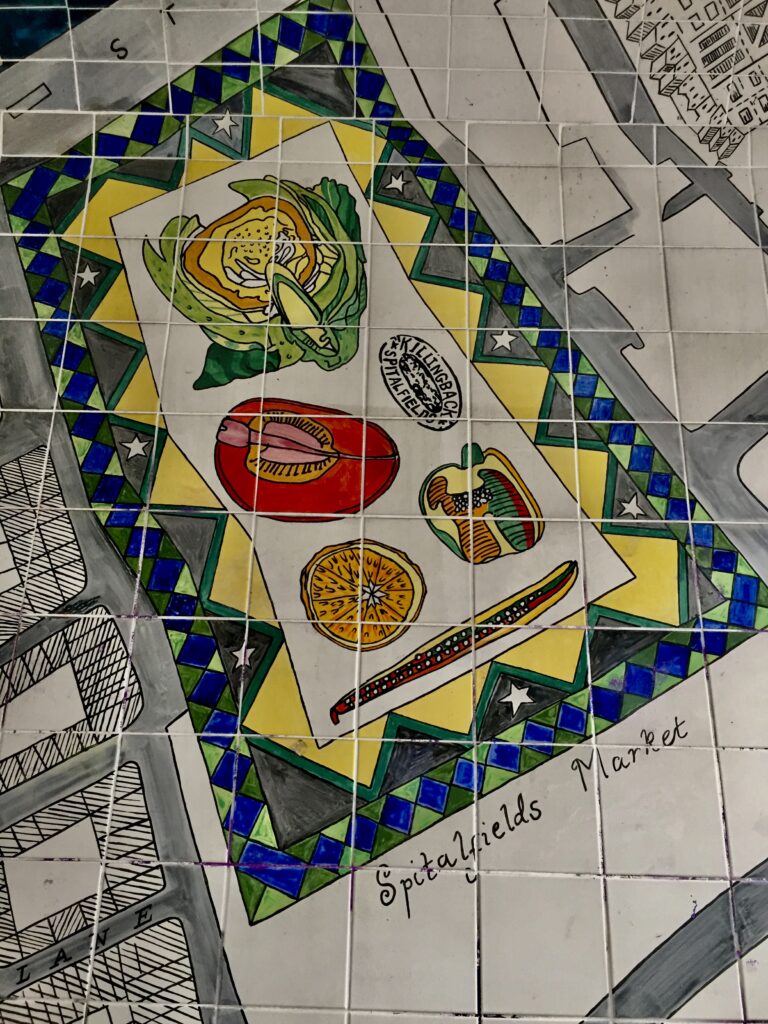

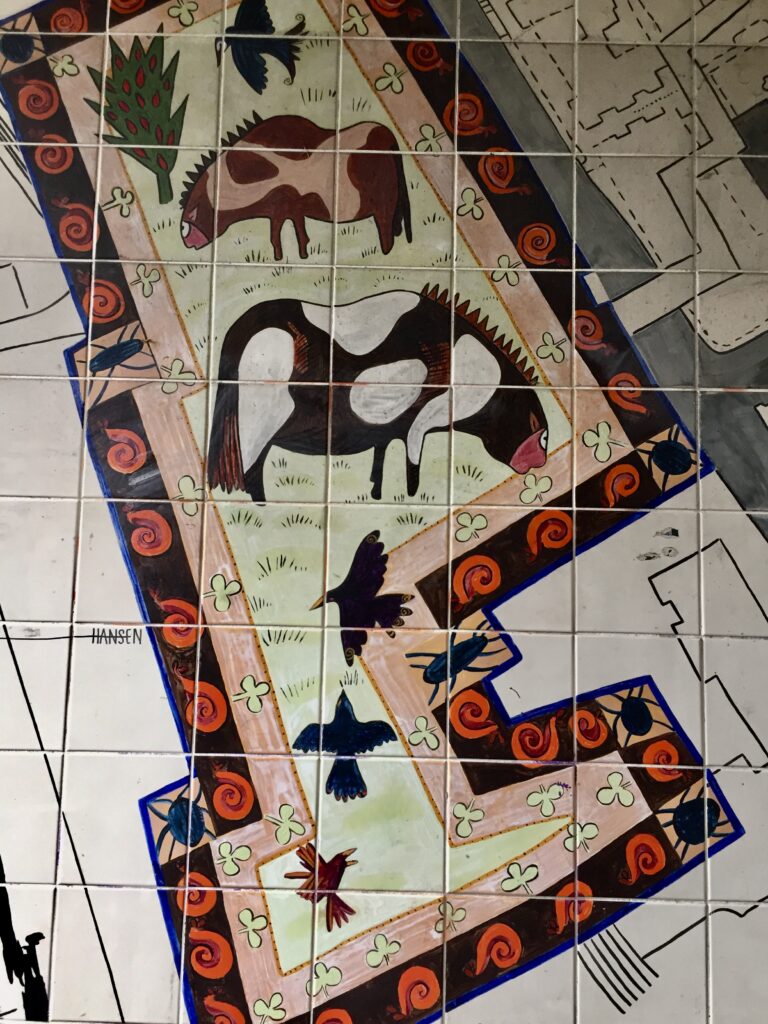

We are reminded, for example, that horses played a tremendous part in work practices, transport, leisure and, sadly, war. It’s estimated, for example, that there were about 3.3 million horses in late Victorian Britain and in 1900 about a million of these were working horses. Of the 62 people commemorated here, five died as a result of an incident involving horses and I shall write about two of them.

Here is the first mention of horses on the wall …

William Drake earned his living as a carriage driver and on this occasion his passenger was one of the most famous sopranos of her day, a lady called Thérèse Tietjens. The breaking of the carriage pole caused panic among the horses and they reared out of control. In fighting to control them, Drake received a severe kick to his right knee which subsequently resulted in the septicaemia that led to his death on April 8th. A message was passed to the coroner at the inquest that ‘those dependent on the deceased would be amply cared for by Madame Tietjens’. Notwithstanding this, Drake was buried at the expense of the parish in a common grave in Brompton Cemetery, although there is evidence that his widow did receive an annuity from somewhere.

Elizabeth Boxall died after being kicked by a runaway carthorse as she pulled a small child out of its way …

Her brave act actually took place in July 1887 but over the next eleven months poor Elizabeth’s health deteriorated. Part of her leg was amputated in September and a further part (up to her hip) in January 1888, her condition being complicated by a diagnosis of cancer. Her parents were distraught by her death and the way she had been treated by the medical profession – for example, the first amputation was carried out without her or her parents’ permission. ‘They regularly butchered her at that hospital’ her father exclaimed at the inquest and the jury found that shock from the second operation was the cause of death. No one from the hospital attended the inquest but the House Governor at the London Hospital disputed the finding in a letter to the press.

Still on a medical theme, the highly contagious infection known as diptheria features twice on the memorials. Now extremely rare due to vaccination programmes, it was once a frequent killer of small children and also posed a danger to physicians such as Samuel Rabbeth …

I have been able to locate a picture of him thanks to the excellent London Walking Tours blog…

Copyright, The British Library Board

On October 10th the doctor was treating a four year old patient who was in danger of asphyxiation as diptheria often resulted in a membrane blocking the airways. The standard treatment of tracheotomy had been performed but to no avail and Rabbeth performed the more risky procedure of sucking on the tracheotomy tube to remove the obstruction. Unfortunately in doing so he contracted the infection himself and died on 20th October (not the 26th as shown on the plaque). There was some (fairly muted) criticism of his actions by doctors who believed he acted recklessly, although from the most honourable of motives.

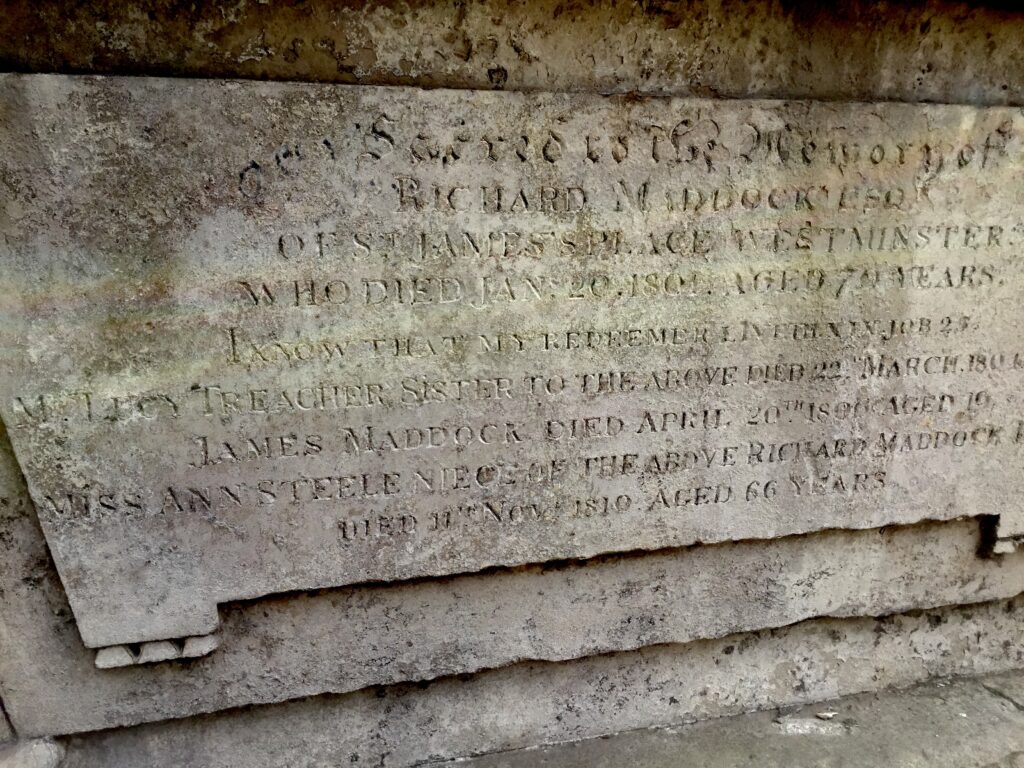

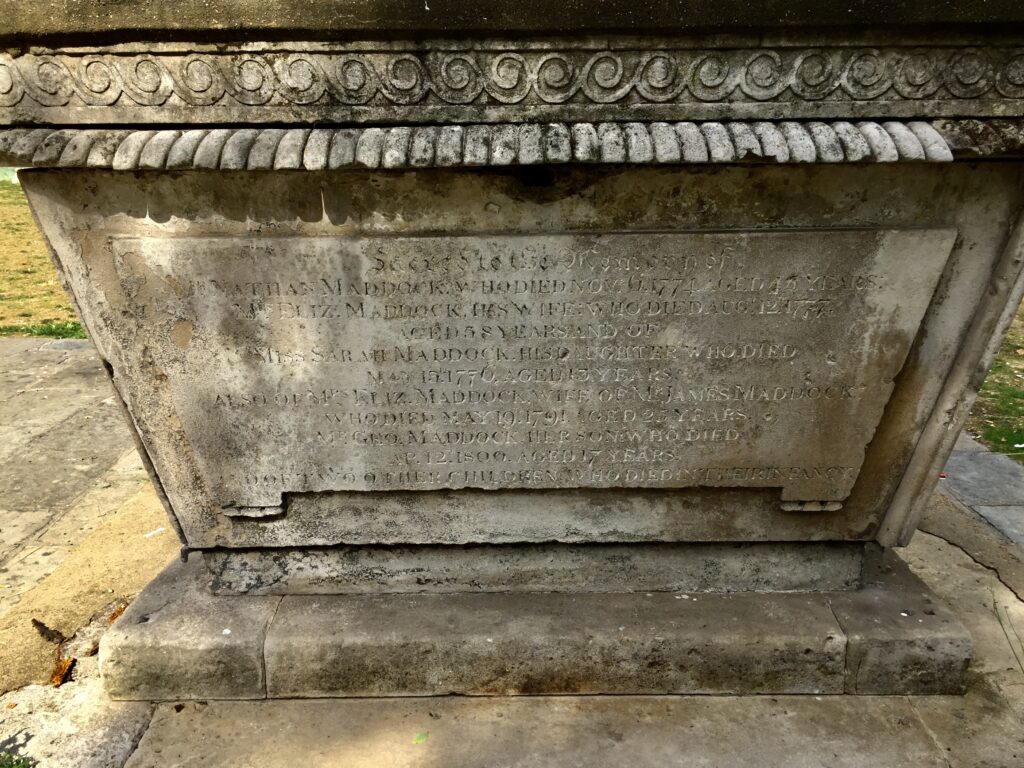

He has a fine gravestone in Barnes Cemetery which gives details of his personal professional history and the circumstances of his death …

Dr Lucas was infected as a result of an unfortunate accident …

He was in the process of administering an anaesthetic to a child with diptheria in order that a tracheotomy could be carried out. The child coughed or sneezed in his face but, instead of delaying to clean himself up, which may have endangered the child’s life, he continued and as a result became infected. He died within a week.

I haven’t been able to find an image of him or his final resting place but a poem written in his memory was published in a number of newspapers and you can read it in full here.

Thomas Griffin was engaged to be married on 16 April 1899 and on 11 April he had travelled to Northampton to discuss arrangements with his family and then back home to Battersea for work the next day. He expected that by the end of the week he would be married, but that was not to be, and by the end of the following day he was dead …

An inquest on 17 April was told that, after an explosion in the refinery boiler room, the door had been closed and the men told to keep out. Griffin, who had been evacuated to safety, suddenly cried out ‘My mate! My mate!’ and before anyone could stop him had disappeared into the boiler room. Terribly scalded all over his body he died later that day. The coroner lamented that …

… the conduct of a man like him deserves to be recorded. No doubt there are heroes in everyday life, but they do not come to the front and so we do not hear of them.

Unbeknown to the coroner, Watts had been collecting newspaper cuttings of heroic acts for years and added Griffin’s story to the growing archive. So it came to pass that Thomas Griffin was among the first four people to be commemorated upon the newly opened memorial.

And finally …

One might get the impression that this gentleman was particularly worthy of recognition because the person he saved was not only a stranger but also a foreigner. This would be a shame if it detracts from a very brave act and a tragic one also since, according to Cambridge’s brother Royston, John need not have perished. He told the Nottingham Evening Post …

My brother, who was a very good swimmer, saw while bathing an unknown person drowning, and swam out to her assistance. The bathing boat rescued the lady, and the other bather, but the boatmen declined to go out again, although we implored them to do so, and offered them payment, until they were ordered out by officials. It was then, of course, too late.

I have written in great detail about the following four heroes in an earlier blog which you can find (along with pictures of three of them) here …

I am indebted for the background research used in this blog to the historian John Price and his incredibly interesting book Heroes of Postman’s Park – Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London. You will find details of how to purchase your copy here.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …