Last week’s blog was largely concerned with the rather gruesome events that took place in this historic area so I’m aiming to be a bit more lighthearted this week.

Looking up as you walk can be very rewarding. Just opposite Smithfield Central Market on Charterhouse Street I spotted this frieze at the top of one of the buildings …

Here is a close up of the panel on the left …

And here’s the one on the right …

Aren’t they wonderful! I’m pretty sure that’s a bull in the foreground.

And, whilst in livestock mode, if you look just around the corner in Peter’s Lane you will encounter this sight (EC1M 6DS) …

Now look up …

Here’s the bull at the very top …

Surprisingly, they only date from the mid-1990s and are made of glass reinforced resin. The bovine theme was used as a decorative motif because for centuries the appropriately named Cowcross Street was part of a route used by drovers to bring cows to be slaughtered. The tower forms part of The Rookery Hotel and also dates from the mid-1990s, although it looks much older due to the use of salvaged bricks.

I reckon this is a top class piece of sympathetic redevelopment by the architects Gus Alexander. Read all about how they approached the work here.

I’ll say a little about Smithfield’s history.

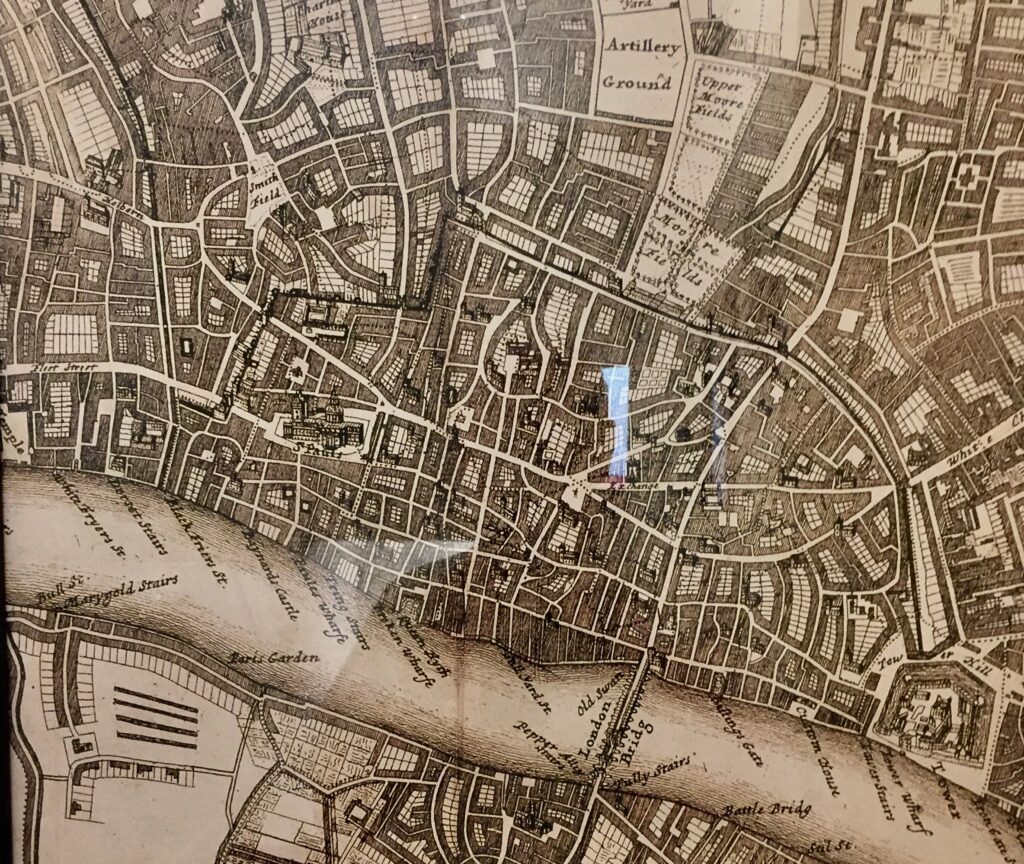

It appears on some old maps as Smooth Field …

In the Braun and Hogenberg map of 1560/72 it’s Smythe Fyeld …

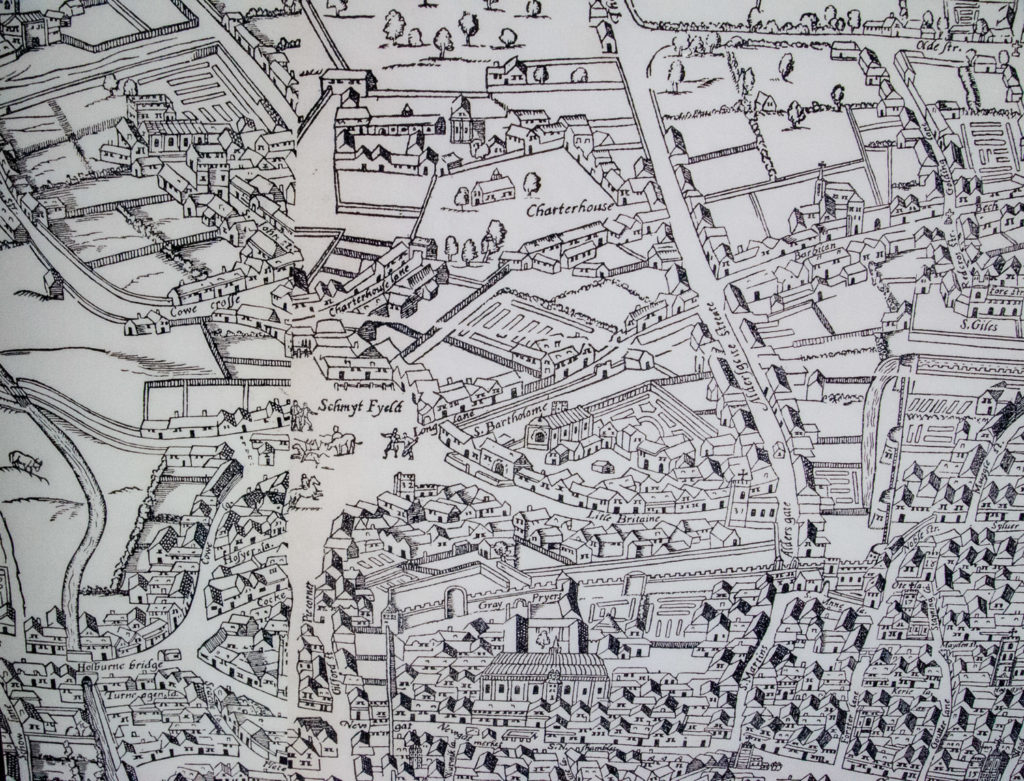

In the Agas Map of 1633 it’s Schmyt Fyeld …

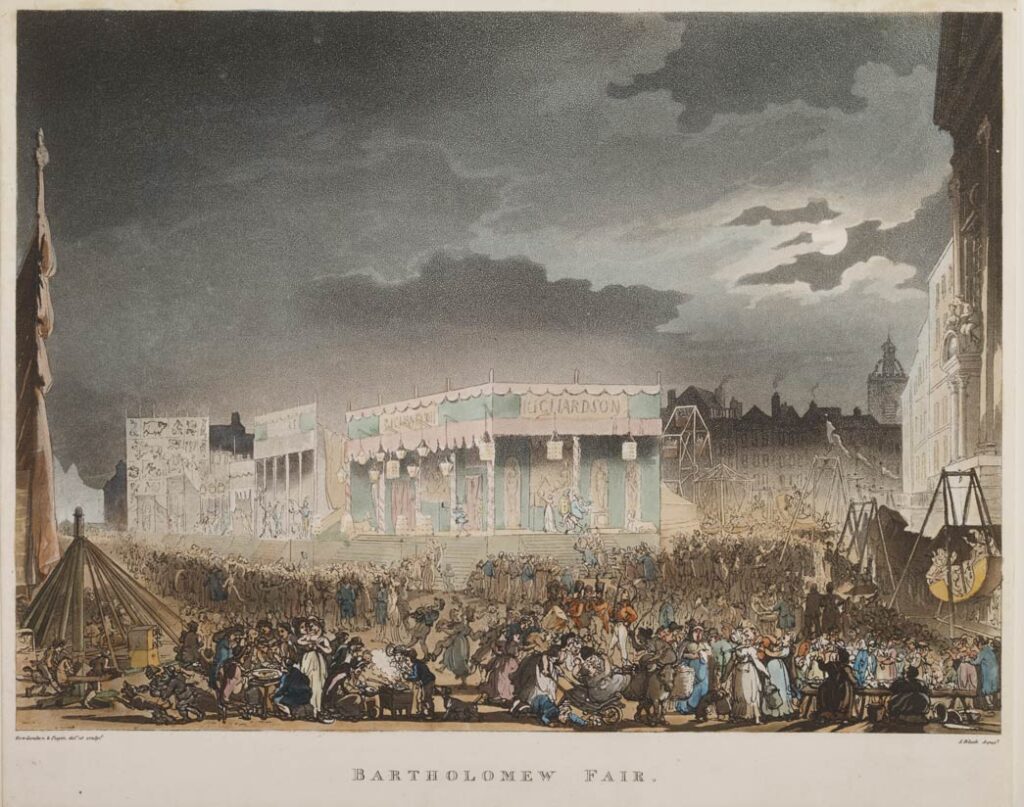

By the twelfth century, there was a fair held there on every Friday for the buying and selling of horses, and a growing market for oxen, cows and – by-and-by – sheep as well. An annual fair was held every August around St Bartholomew’s Day and was the most prominent and infamous London fair for centuries; and one of the most important in the country. Over the centuries it became a teeming, riotous, outpouring of popular culture, feared and despised like no other regular event by those in power… ‘a dangerous sink for all the vices of London’. This image gives a flavour of it …

In the foreground, a man digs deep into his pocket. It looks like he’s just about to place a bet on a ‘find the pea’ game – a notorious confidence trick being operated here by a distinctly dodgy looking character. In the background musicians play and people dance.

Here’s another view that captures the sheer exuberance of the event …

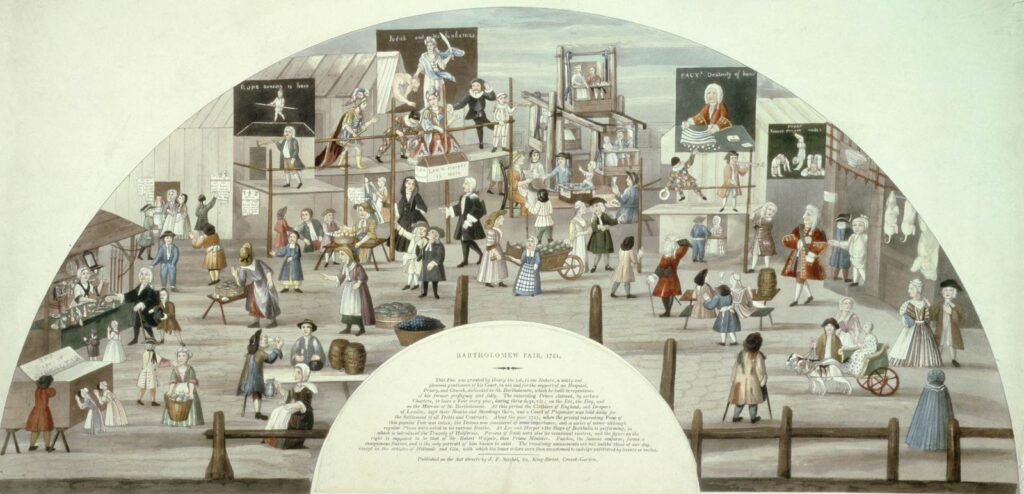

In this 1721 image the behaviour looks more sedate …

In 1815 Wordsworth visited the Fair and saw …

Albinos, Red Indians, ventriloquists, waxworks and a learned pig which blindfolded could tell the time to the minutes and pick out any specified card in a pack.

Alongside the entertainment of the Fair there was an undercurrent of trouble, violence and crime. In 1698 a visiting Frenchman, Monsieur Monsieur Sorbière, wrote …

I was at Bartholomew Fair… Knavery is here in perfection, dextrous cutpurses and pickpockets … I met a man that would have took off my hat, but I secured it, and was going to draw my sword, crying, ‘Begar! You rogue! Morbleu!’ &c., when on a sudden I had a hundred people about me crying, ‘Here, monsieur, see Jephthah’s Rash Vow.’ ‘Here, monsieur, see the Tall Dutchwoman’ …

After more than 700 years the Fair was finally banned in 1855 for being …

A great public nuisance, with its scenes of riot and obstruction in the very heart of the city.

As far as livestock trading was concerned it had always been a place of open air slaughter. The historian Gillian Tindall writes: ‘Moo-ing, snorting and baa-ing herds were still driven on the hoof by men and dogs through busy streets towards Smithfield, sometimes from hundred of miles away. Similarly, geese and ducks were hustled along in great flocks, their delicate feet encased in cloth for protection. They were all going to their deaths, though they did not know it – till the stench of blood and the sounds of other animals inspired noisy fear in them’.

In Great Expectations, set in the 1820s, young Pip comes across the market and refers to it as ‘the shameful place, being all asmear with filth and fat and blood and foam [which] seemed to stick to me.

Eventually slaughtering was moved elsewhere and the open air market closed in 1855 …

The present meat market on Charterhouse Street was established by an 1860 Act of Parliament and was designed by Sir Horace Jones who also designed Billingsgate and Leadenhall Markets. Work on Smithfield, inspired by Italian architecture, began in 1866 and was completed in November 1868. I think this picture was taken not long after construction …

The buildings were a reflection of the modernity of Victorian city. Like many market buildings of the second half the nineteenth century, they owed a debt to Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in their creative use of glass, timber and iron …

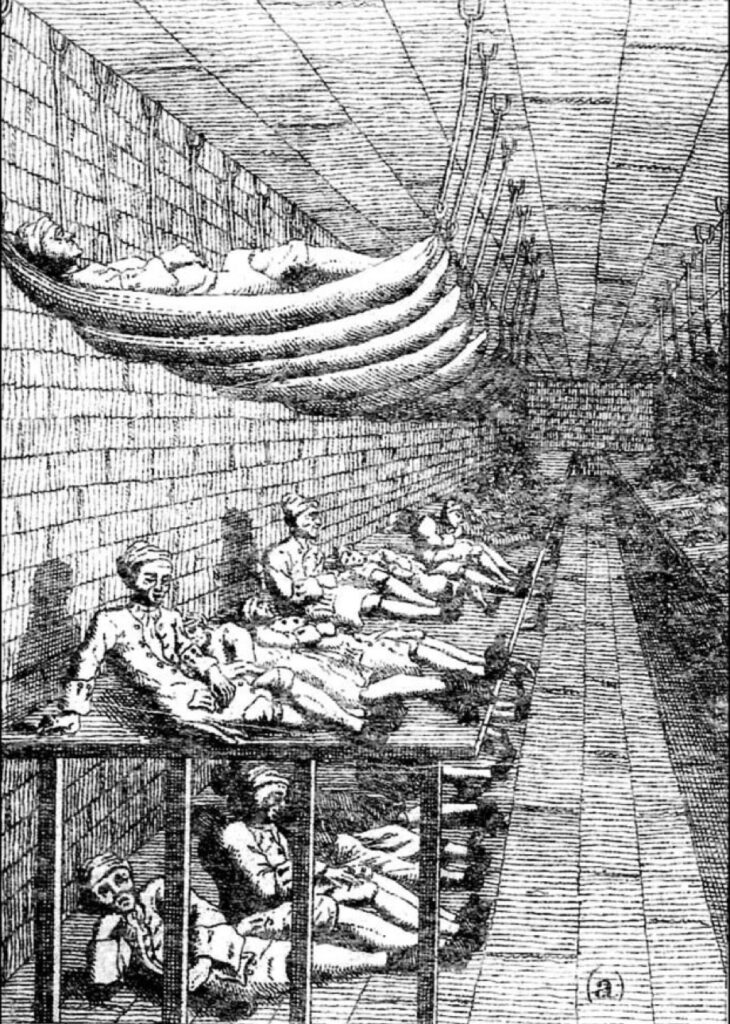

One aspect of the London Central Markets, as the Smithfield buildings were known, was particularly revolutionary, though largely hidden. All the buildings were constructed over railway goods yards. For the first time ever, meat was delivered by underground railway direct to a large wholesale market in the centre of a city. In this picture, an underground train whizzes past where the old tracks used to be …

The spectacular colour scheme today replicates what it was when the market opened …

The church of St Bartholomew the Great is always worth a visit but today I’ll just mention the Gatehouse entrance. These pictures show the site before and after the first world war …

The Zeppelin bomb that fell nearby in 1916 partly demolished later buildings revealing the Tudor origins underneath and exposing more of the 13th century stonework from the original nave. By 1932 it was fully restored.

Looking out towards Smithfield you can see the 13th century arch topped by a Tudor building …

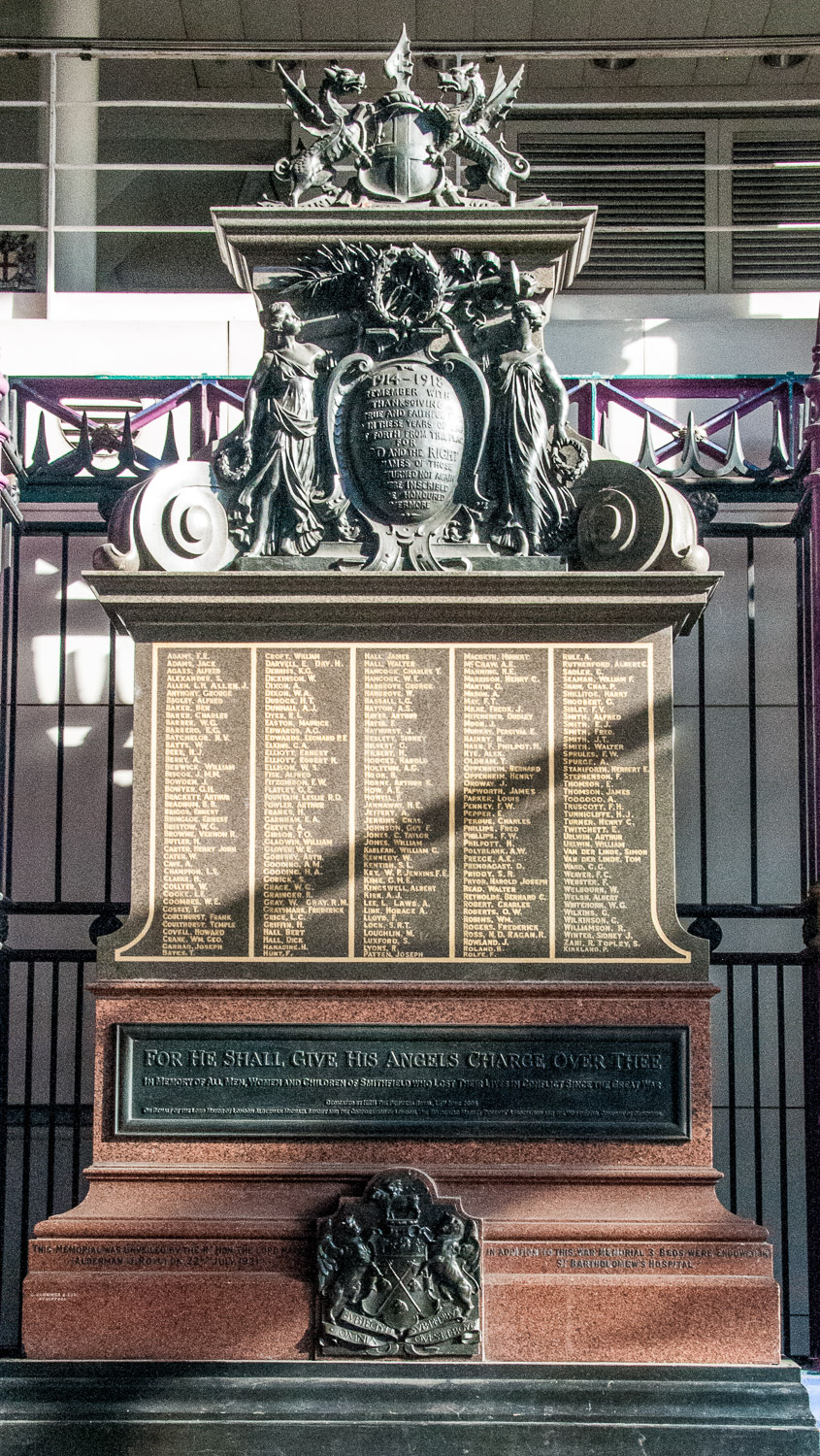

Finally, in the Great Avenue (EC1A 9PS), there is this monument commemorating men, women and children who perished both overseas and nearby …

The original memorial (above the red granite plinth) is by G Hawkings & Son and was unveiled on 22 July 1921. 212 names are listed.

Between Fame and Victory holding laurel wreaths, the cartouche at the top reads …

1914-1918 Remember with thanksgiving the true and faithful men who in these years of war went forth from this place for God and the right. The names of those who returned not again are here inscribed to be honoured evermore.

At 11:30 in the morning on 8th March 1945 the market was extremely busy, with long queues formed to buy from a consignment of rabbits that had just been delivered. Many in the queue were women and children. With an explosion that was heard all over London, a V2 rocket landed in a direct hit which also cast victims into railway tunnels beneath – 110 people died and many more were seriously injured. This picture shows some of the terrible aftermath …

The monument was refurbished in 2004/5 and unveiled on 15 June 2005 by the Princess Royal and Lord Mayor Savory. The red granite plinth had been added and refers to lives lost in ‘conflict since the Great War’. On it mention is made of the women and children although the V2 event is not specifically referred to.

This is the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Butchers who helped to fund the refurbishment, along with the Corporation of London and the Smithfield Market Tenants’ Association.

The crest translates as : ‘Thou hast put all things under his feet, all Sheep and Oxen’.

Plans have been made for the market to be moved, along with Billingsgate and New Spitalfields markets, to Barking Reach power station, an abandoned industrial site at Dagenham Dock earmarked for redevelopment. The Museum of London will relocate to part of the old market site.

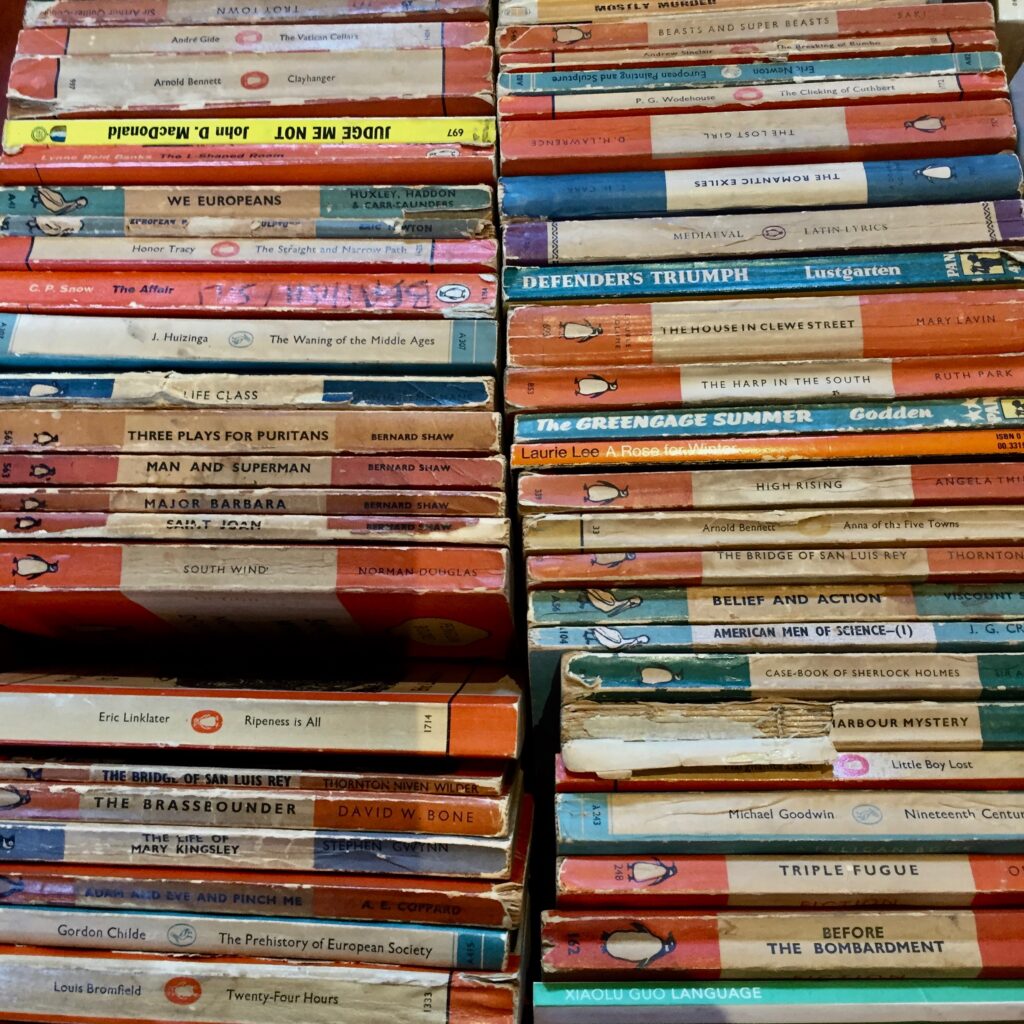

If you want to read more about Smithfield and its history, here is a link to some of my sources:

Smithfield’s Bloody Past by Gillian Tindall.

Today in London’s festive history – The opening of Batholomew’s Fair.

St Bartholomew’s Gatehouse | A rare survivor of 16th century London.

Underneath Smithfield Market – The Gentle Author.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …