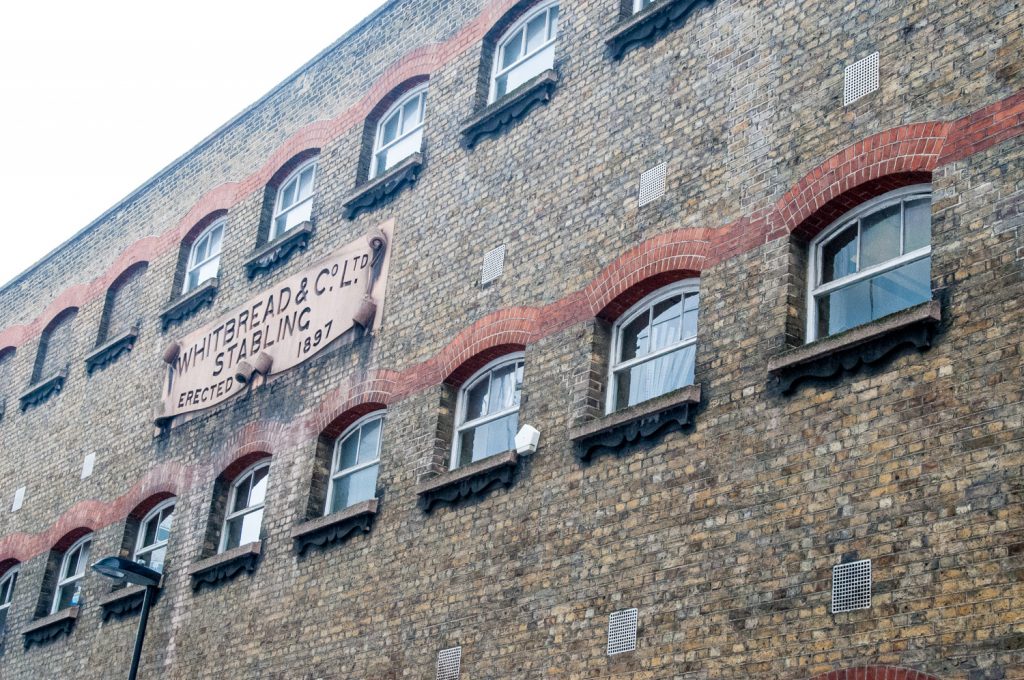

Take a stroll down Garrett Street (EC1Y 0TY) and you’ll soon be walking past a building that still survives to remind us of the end of two great eras – the age of horse-drawn transport and the once-thriving brewing industry in London. These were the stables custom-built for the dray horses that pulled the Whitbread Brewery wagons. When the brewery’s stables in Chiswell Street became full, Garrett Street was built to take the overflow – 13 horses on the ground floor, 36 on the first floor and over 50 on the top. The building had to be well constructed – a shire horse can weigh up to a ton.

I think these are the original gates, now painted a rather dramatic yellow …

At the rear you can see the individual stables on the ground floor …

The internal stairs reflect the gentle slope underneath that made it easy for the horses to be led to the upper floors …

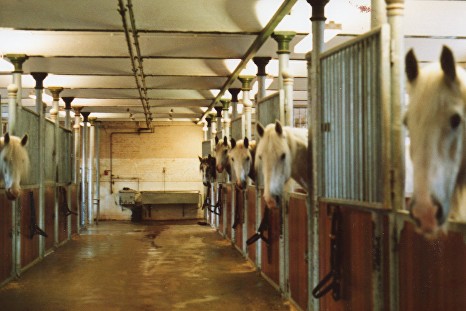

The first floor stables in 1991 …

Some of the original features are still visible today …

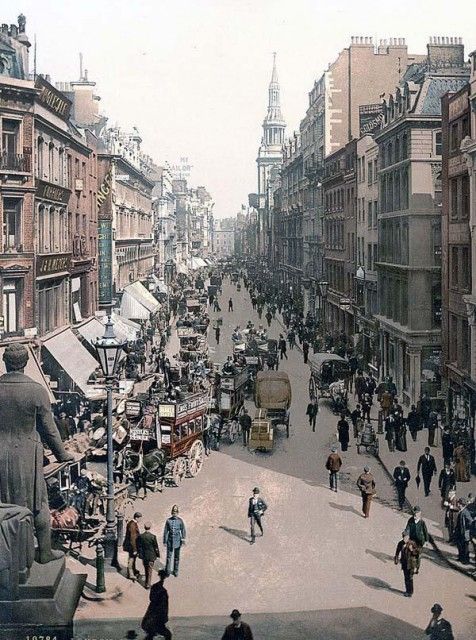

In 1897, when the Garrett Street stables were built, there were over 50,000 horses transporting people around the city every day – several thousand horse buses (which needed 12 horses per day) and 11,000 Hansom cabs. In addition there were thousands of horse drawn carts and drays, like Whitbread’s, delivering goods around what was then the largest city in the world.

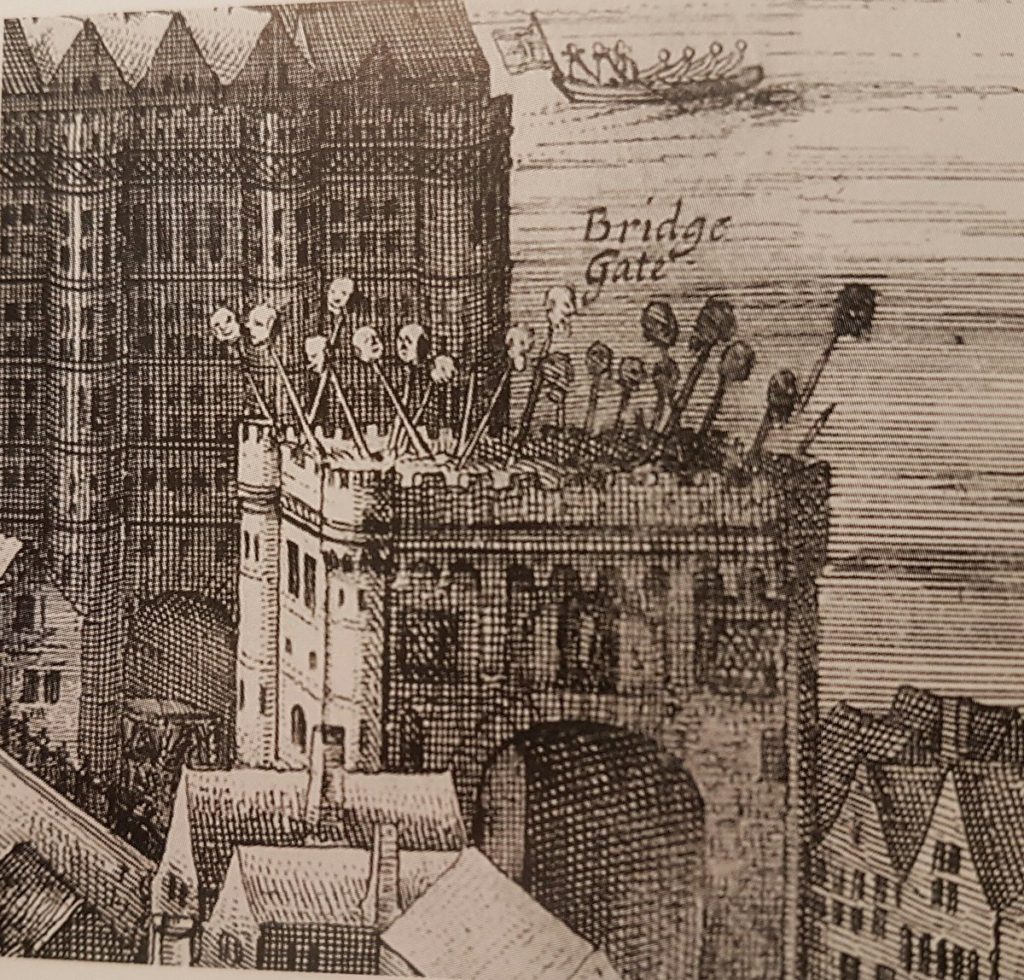

In this 19th century image you are looking east down Cheapside with the statue of Sir Robert Peel in the foreground (along with one of his uniformed ‘Bobbies’) …

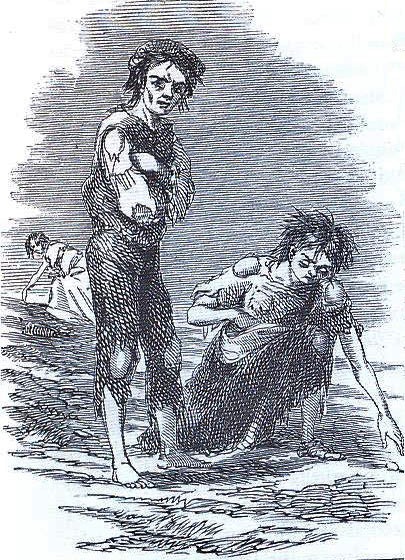

The presence of so many horses in the already congested city had major implications for the health of the population. On average each horse would produce between 15 and 35 pounds of manure every day plus several pints of urine and this attracted huge numbers of disease-carrying flies. Also, working horses only had a working life of about three years and many collapsed and died in the street. These carcasses had to be disposed of but often the bodies were left to putrefy so the corpses could be more easily sawn into pieces for removal.

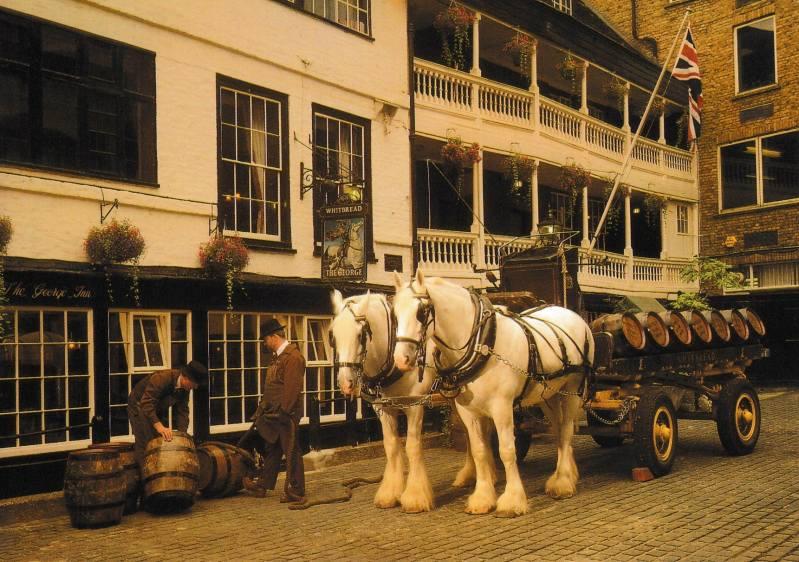

Some working animals led terrible, short, brutal lives, but clearly the Whitbread horses were far better cared for. We should spare a thought, though, for the 118 of their best horses that were commissioned by the Government for service in the battlefields of the First World War – none ever returned.

In happier times, Whitbread Shires were delivering ale well into the 20th century …

The brewing business was formed in 1742 when Samuel Whitbread formed a partnership with Godfrey and Thomas Shewell and acquired a small brewery at the junction of Old Street and Upper Whitecross Street and another brewhouse for pale and amber beers in Brick Lane. The entire operation was moved to Chiswell Street in 1750 and was spectacular enough to attract a visit from King George III and Queen Charlotte which this plaque commemorates …

The size of the premises is still impressive today, although the building is now a hotel (EC1A 4SA) …

As you walk through the arched entrance you see an impressive mahogany door on the right …

Then you enter the main yard itself with its overhanging gantries …

The old clock is still there …

And there is a weathervane incorporating the old Whitbread hind’s head logo over the 1912 extension, now dwarfed by the Barbican’s Cromwell Tower …

The yard is still cobbled …

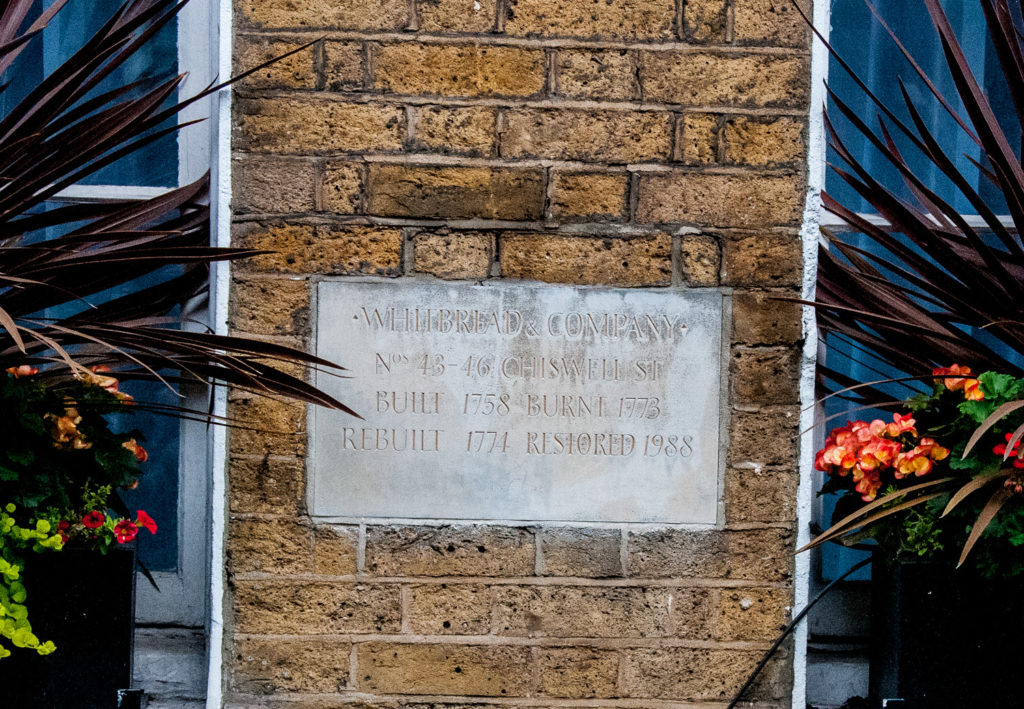

Just visible across the road is the appropriately named Sundial Court. Also once part of the Brewery site, the sundial itself is now behind locked security gates but is still visible from the road. It is made of wood, with its motto ‘Such is Life’, dating back to 1771. Around the sides it has the interesting inscription Built 1758, burnt 1773, rebuilt 1774. I have written about it and other City sundials in an earlier blog, We are but shadows.

Adjacent to Sundial Court are the houses used by the Brewery partners …

A plaque on the wall also references the fire of 1773 …

Brewing at Chiswell Street stopped in 1976 and Whitbread stopped brewing beer altogether in 2001, selling all its operations to the Belgian group Interbrew.

A mere ten years after the stables were built, horse traffic was rapidly vanishing from the streets of London to be replaced by motorised vehicles such as this …

The last horses left the Garrett Street stables on Monday 16th September 1991, heading for their new home on the Whitbread hop farm in Paddock Wood, Kent.

If you want to know more about the fascinating history of the Whitbread Shire horses and their stables there is no better place to look than the website run by John Sparks : http://whitbreadshires.moonfruit.com/#

By the way, whilst doing my research I came across an interesting example of the danger of forecasting. In 1894 The Times newspaper predicted …

In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.

I now always think of this when reading forecasts in today’s press and there was an interesting article on this very subject in the Financial Times which you can read here.