This week’s blog was prompted by a gift we received – a wonderfully crafted baby dragon from Little Dragon Designs . He’s very small, only just over three inches wide, but very meticulously detailed …

It reminded me that the City is full of dragons and that it has been a long time since I paid them a visit.

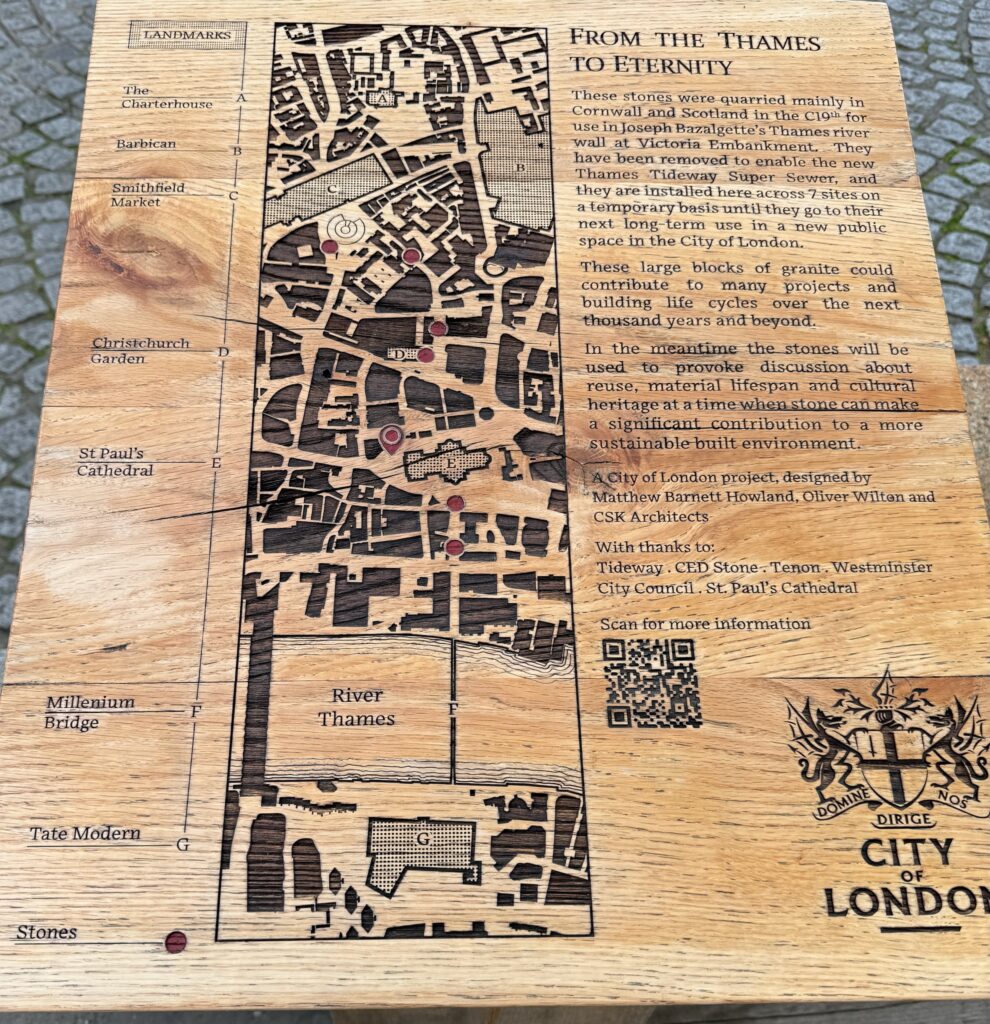

In 1963 the Government was redrawing local government boundaries and the City Corporation had to decide how its area of control should be identified. Rather than someting bland and commonplace (e.g. Welcome to the City – Please Drive Carefully) they looked for something a bit more dramatic.

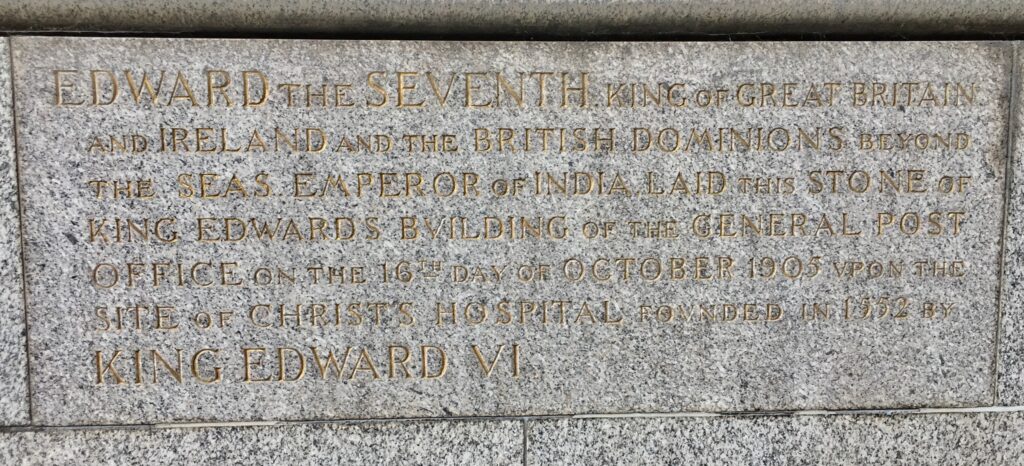

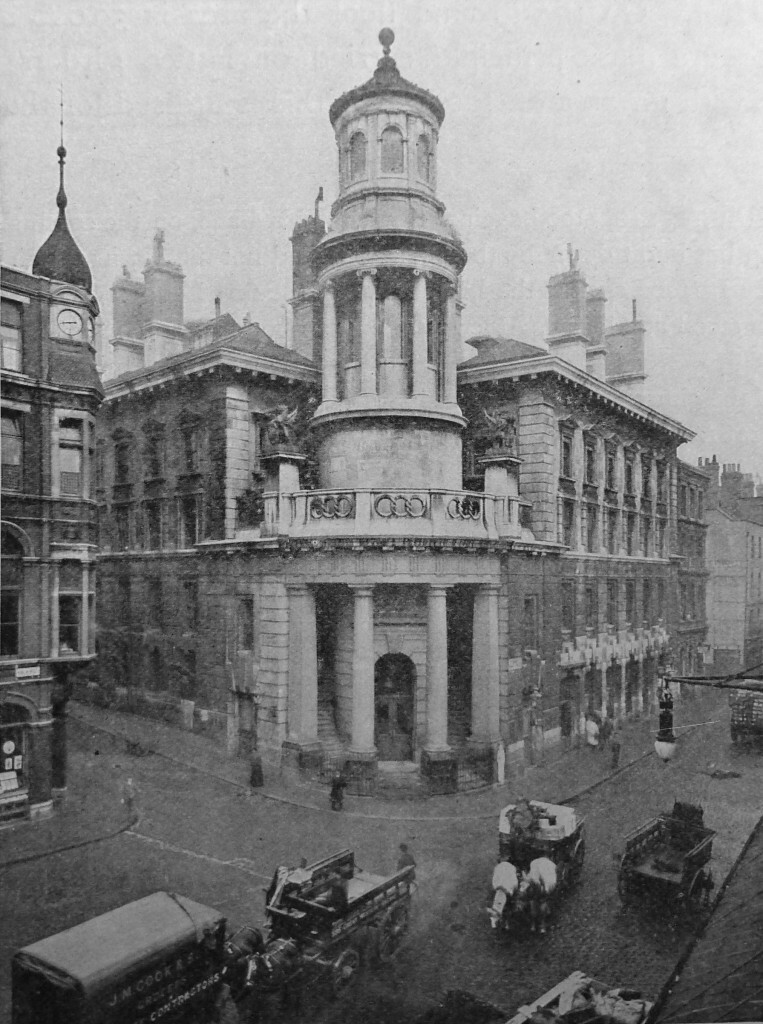

Their final choice to use dragons was facilitated by the controversial decision to demolish the Coal Exchange in Lower Thames Street. The trade in coal in London was hugely important, not just because it fuelled the city, but thanks to taxes that were introduced after the Great Fire of London, it funded a lot of London building works. The Coal Exchange was built in 1847 to help manage the trade and, high above the main entrance, two plinths held two large cast-iron dragons. Here it is around 1900 …

When the Exchange was demolished, the City of London Streets Committee conceived the idea of preserving the dragons as boundary markers, and they were inaugurated in their new home on Victoria Embankment on 16 October 1963 where they remain to this day …

They were originally cast, by the London founder Dewer, in 1849, as can be seen on the back of the shield …

These original dragons are seven feet tall but half size replicas were created for deployment around 11 other entry points to the City.

Before I go on to share more dragons with you the first thing I must be clear about is that the City symbol is a dragon and not a griffin (as is still mistakenly stated in many City guides).

The legendary griffin (or gryphon) is a creature with the body, tail and back legs of a lion; the head and wings of an eagle; and an eagle’s talons as its front feet. I have only been able to find one in the City and here it is at the entrance to Dunster Court in Mincing Lane …

He proudly supports the arms of the Clothworkers Company.

Dragons, on the other hand, have a barbed tail, tend to be scaly all over and breathe fire and smoke. Here is the City of London version on Tower Hill …

It is made of cast iron and painted in silver with details picked out in red. It supports a shield with the City emblem of the red cross of St George and the short sword of St Paul, the City’s patron saint.

Guarding the boundary between the City of London and Westminster, the Temple Bar Dragon is in a league of its own. It is taller, fiercer, very gothic and is black rather than silver. It would be quite at home in a Harry Potter story and is quite scary – maybe that’s why the Corporation Committee Chairman, having considered the Temple Bar version, chose the less flamboyant Coal Exchange dragons as boundary markers instead …

Another dragon at Temple Bar faces towards Westminster …

A Times writer commented that it ‘wears an aspect of defiance similar to that of the lion surmounting the mound on the field of Waterloo’.

Once you get your eye in, so to speak, you will find dragons everywhere.

This Smithfield Market beast looks like he is just about to swoop down – perhaps for a meaty lunch …

And these two work hard supporting the roof of Leadenhall Market …

One might pop up unexpectedly as you cross Holborn Viaduct …

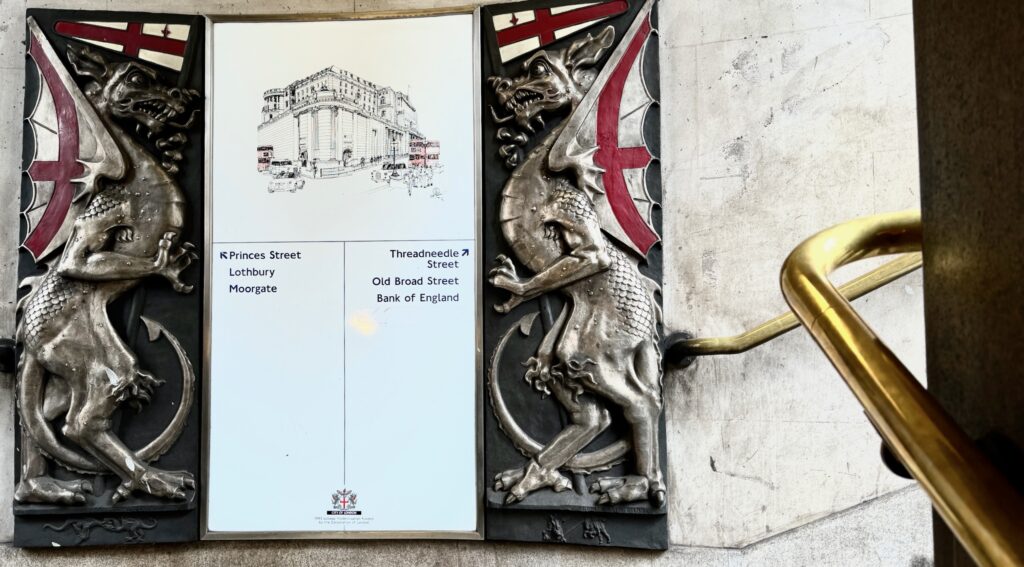

You encounter this formidable pair as you leave Bank Underground Station …

More delicate versions adorn the lamps outside the Royal Exchange …

The City’s coat of arms atop the Guildhall …

And on the newer building nearby …

The City’s Latin motto : Lord guide us.

A more modern version (also at the Guildhall) …

You will find a fascinating article about the City coat of arms here.

If you are fascinated by dragons, or know someone who is, I highly recommend a visit to the Little Gragon Designs website. A vast selection of dragon-related gifts!

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …