In last week’s blog I talked about cruise liners and curves. This week it’s castles, crenellations and concrete (I am familiar with the rule ‘always avoid annoying alliteration’ but I just couldn’t help myself).

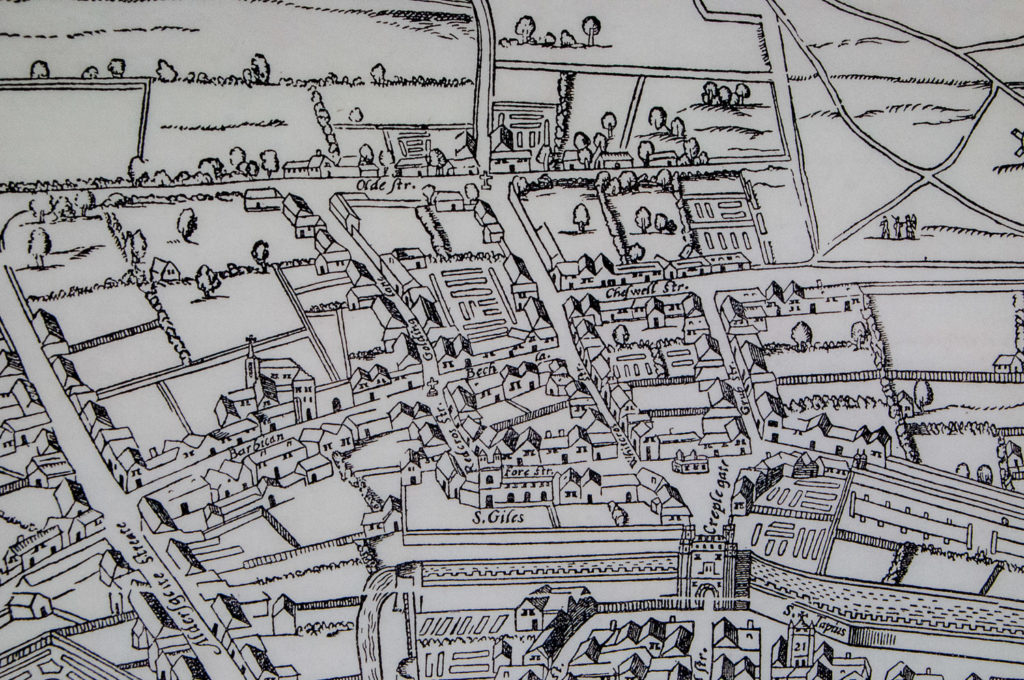

‘Barbican’ used to be the name of a street in a bustling commercial area in the ward of Cripplegate. By the end of the 19th century it was the centre of the rag trade and was home to fabric and leather merchants, furriers, glovers and a host of other tradesmen. You can see it on the so-called Agas map of 1633 …

On the 29th December, 1940, at the height of the Second World War, an air raid by the Luftwaffe razed virtually the entire surrounding area to the ground.

The word (from Old French: barbacane) means a fortified outpost or gateway, such as an outer defence to a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes. And it’s easy to spot the architects’ references to that function as you walk around the 35 acre estate.

What about this entrance to the art gallery …

Those steps look formidable, and those crenellations (aka battlements) look like they are there to house a castle’s defenders.

Inside the walls are thick and the gates ready to be clanged shut against intruders …

More battlements look down on the Sculpture Court …

Where you can also spot some slits for archers to use …

Along the highwalk the archers’ reference is even more obvious …

It can also be seen on the extraordinary pyramid-topped entrance on Aldersgate, and even the bridge looks like a defensive structure (I’m thinking World War 2 pill boxes) …

Interesting shadows form at certain times of day …

The architecture responds very well to being photographed in monochrome, for example these crenellations at the top of the towers …

And this vertiginous view …

These classical looking columns appear to support the structure …

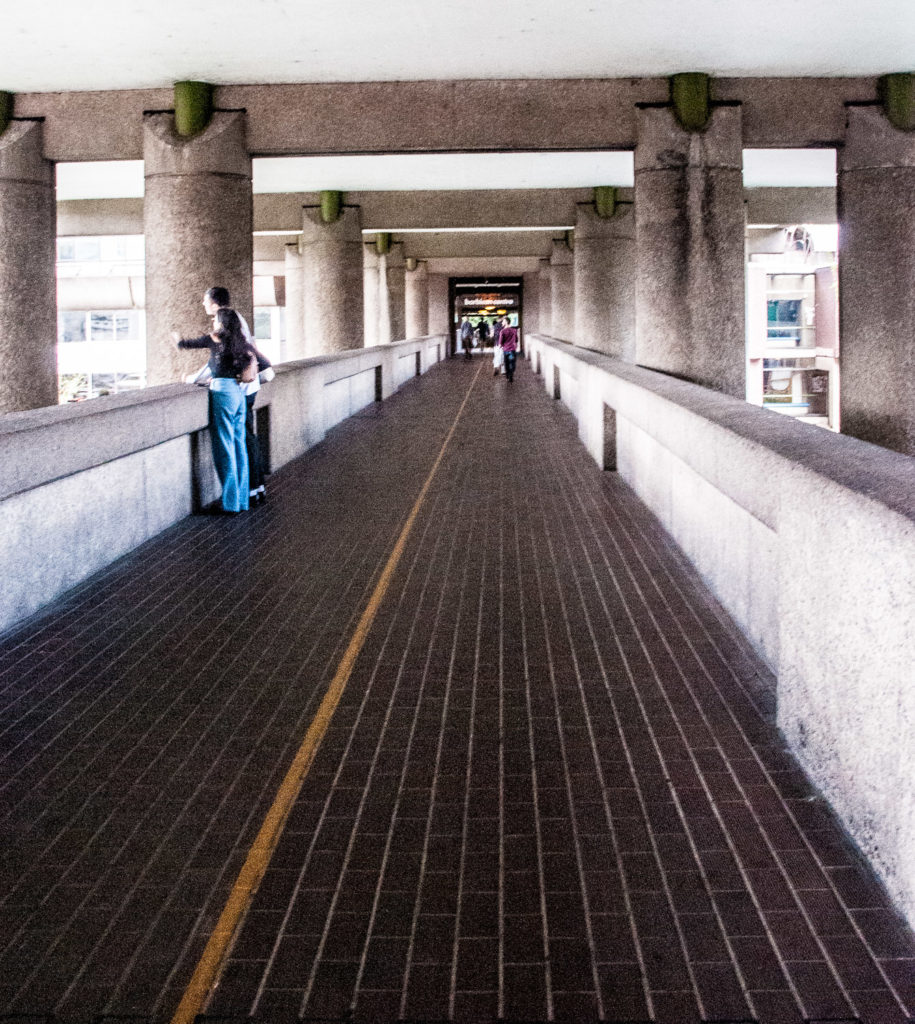

The Barbican is the best surviving example of the post-war plan to separate pedestrians and traffic using raised pavements, rather clumsily called ‘pedways’. The plan failed due to a combination of the need to protect listed buildings, lack of coordination and the public’s reluctance to climb away from street level and embrace a new elevated world.

You can observe this part of the highwalk stopping in mid-air, its further progress into the City impeded by the wall of the Museum of London …

The often-derided yellow line was painted to help visitors navigate their way to the Centre …

It reminds me of a drawbridge over a moat since I saw it from the east end of the estate …

There was a plan at one time to run a road through the development roughly where Gilbert Bridge is now in order to preserve the north-south access lost in the bombing. Needless to say the architects objected and their argument prevailed.

The architecture here is often described as Brutalist, the term being derived from the French béton brut, meaning raw or unfinished concrete. Although the concrete at the Estate was left exposed, it was not unfinished, having been pick-hammered to give it a rough, rusticated appearance implying a sense of monumentality. You can see examples of raw and pick-hammered concrete side by side at the entrance to the Conservatory …

Getting the desired effect was incredibly labour intensive. After the concrete had dried for at least 21 days, workers used handheld pick-hammers or wider bush-hammers to tool the surface and expose the coarse granite aggregate …

We were told that the hammering needed for the entire Estate, including the towers, was carried out by a team of only six men.

Our tour guide not only imparted information about the architecture but also lots about the history of the Estate and the surrounding area. Highly recommended! It’s free and you can book on the website.