I do like a good clock story and the City has quite a few of them – from the clock that killed a man to the one mentioned in a famous poem.

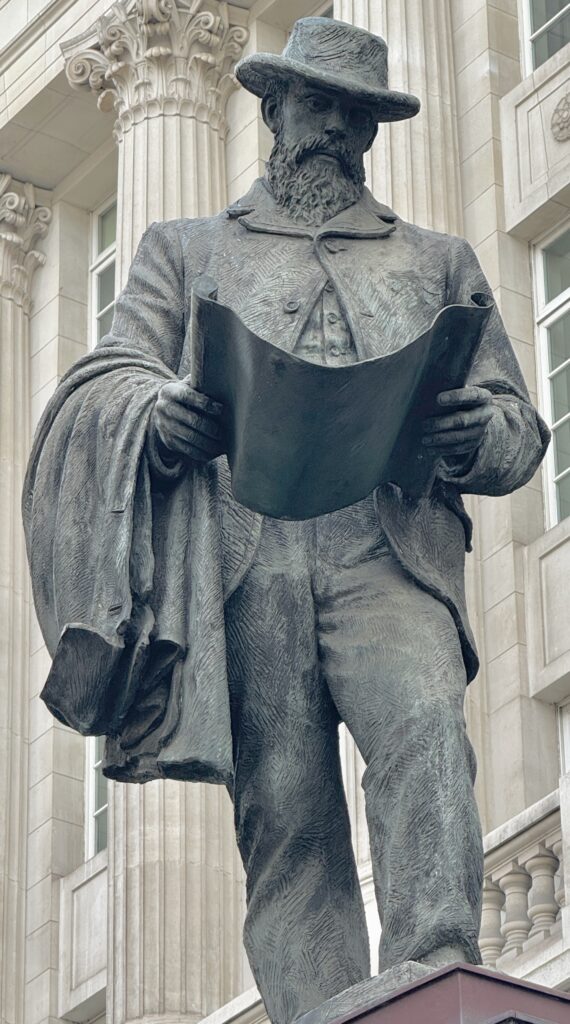

I’ll start, however, with this beauty sited alongside St Magnus the Martyr on Lower Thames Street (EC3R 6DN) …

The clock was the gift of the Lord Mayor, Sir Charles Duncombe. The story goes that when he was a young apprentice, and rather poor, he missed an important meeting with his master on London Bridge because he had no way of telling the time. He vowed that, if ever he became rich, he would erect a clock in the vicinity and this magnificent example of the clockmakers’ art was the result. The artisan was Langley Bradley of Fenchurch Street who had worked with Sir Christopher Wren on several projects, including the early clock that adorned St. Paul’s Cathedral. Wren was evidently impressed with Bradley’s work since, in a letter the Lord Chamberlain’s Office in 1711, he went so far as to describe him as ‘a very able artist, very reasonable in his prices’.

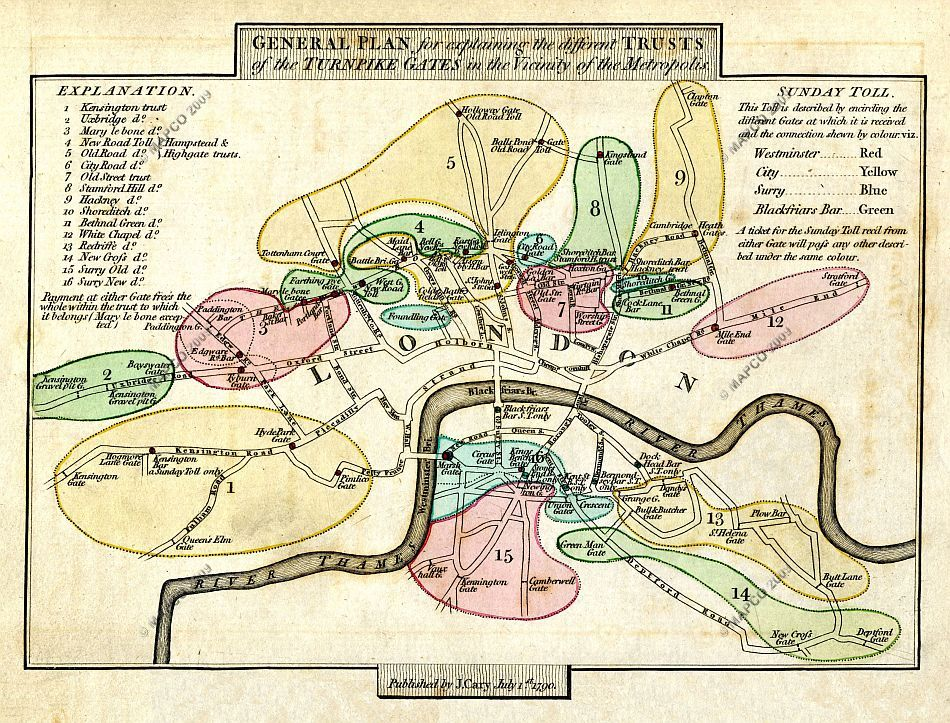

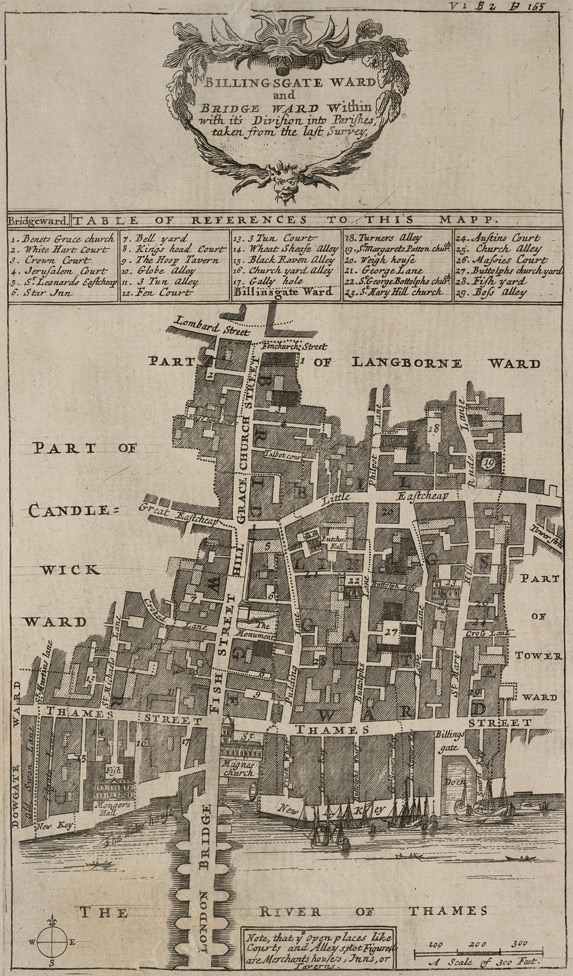

In 1709 St Magnus was located at the north side of the ‘old’ London Bridge as this 18th century map illustrates …

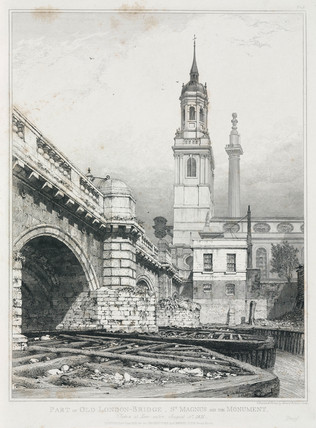

You can also see the clock and its proximity to the bridge in this etching by Edward William Cooke entitled Part of Old London-Bridge, St Magnus and the Monument, taken at Low-water, August 15th, 1831.

Some of you may remember the charming neo-gothic Mappin & Webb building that was controversially demolished in 1994 …

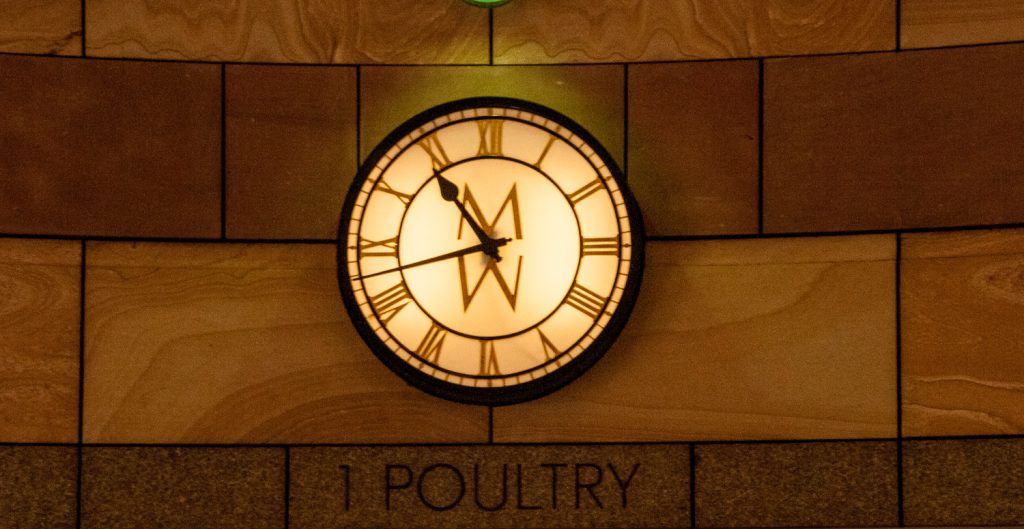

It was replaced by Number 1 Poultry, designed by James Stirling and destined to become the youngest City building to be listed as Grade II* …

Prince Charles was unimpressed and said it resembled ‘a 1930s wireless set’.

I prefer it, however, to the Mies van der Rohe skyscraper that was also considered …

If you walk through the new building at street level you’ll see that the old Mappin & Webb clock has been incorporated …

And a wonderful frieze from the old building illustrating royal processions has also been preserved and relocated facing Poultry. Here is a small section …

Now the clock that killed a man. Here it is attached to the Royal Courts of Justice – designed by George Edmund Street, it has been described as ‘exuberant’ …

On 5th November 1954 a clock mechanic, Thomas Manners, was killed when his clothes were caught up in the machinery as he wound up the mechanism. He had been carrying out this task every week since 1937, as well as looking after the 800 or so other clocks in the law court buildings. You can read the press cutting I came across here.

In 1711 Nicholas Hawksmoor was fifty years old yet, although he had already worked with Christopher Wren on St Paul’s Cathedral and for John Vanbrugh on Castle Howard, the buildings that were to make his name were still to come. In that year, an Act of Parliament created the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches to serve the growing population on the fringes of the expanding city.

Only twelve of these churches were ever built, but Hawksmoor designed six of them and – miraculously – they have all survived, displaying his unique architectural talent to subsequent generations and permitting his reputation to rise as time has passed. One of them is St Mary Woolnoth.

The outside of the church is very unusual and it has a fine position on the corner of King William Street and Lombard Street, just off the major Bank road junction (EC3V 9AN). The clock is mentioned in a famous poem …

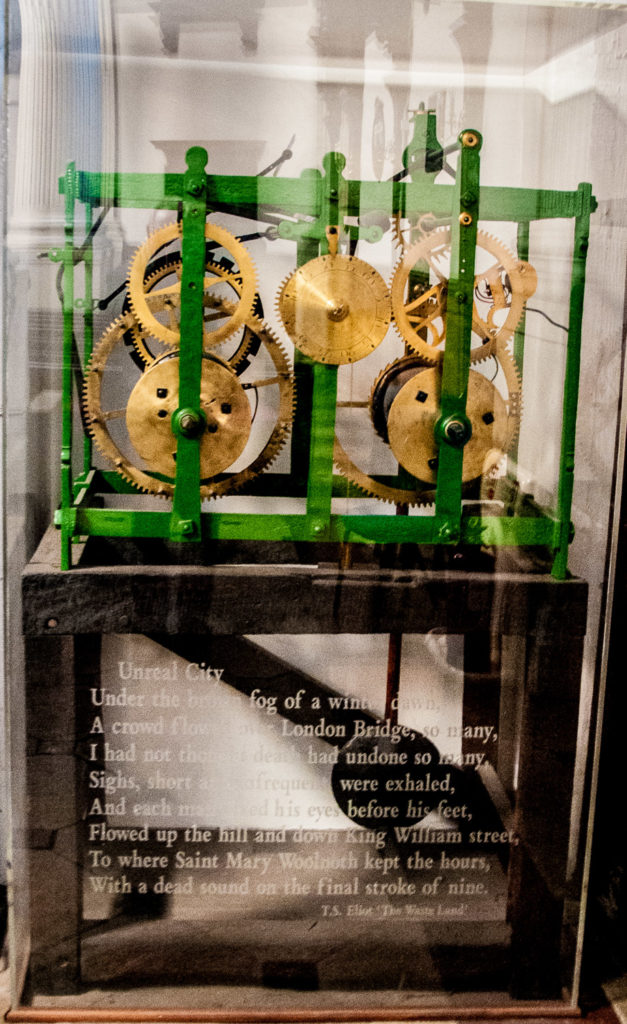

In a corner sits the clock’s mechanism surrounded by a cover on which is etched an extract from T.S. Eliot’s poem The Wasteland …

Eliot worked nearby in Lloyds Bank and, having watched the commuters trudge over London Bridge, wrote these cheerful lines …

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

No doubt if you were not at the office by the ‘final stroke of nine’ you were going to be late.

I have always liked this clock at the corner of Fleet Street and Ludgate Circus …

I read somewhere that, during the Blitz, an incendiary device became entangled in the ball at the top and dangled there for hours until it was deactivated. I often have this image in my head of gently swaying ordnance when I walk up Fleet Street.

The building was originally the London headquarters of the Thomas Cook Travel Agency and, since Mr Cook was a keen supporter of the temperance movement, the first floor contained a temperance hotel. The building is adorned with numerous charming cherubs …

There are dozens of City cherubs and I have written about some of them here.

The Royal Exchange has two ‘twin’ clocks, both exactly the same, one facing Threadneedle Street and one facing Cornhill …

Britannia and Neptune hold a shield that contains an image of Gresham’s original Royal Exchange whilst above Atlas lifts a globe. I have seen it described as a Valentine’s Day clock because of the two red hearts. Ahhhh, sweet!

Here’s Atlas again, straining under his burden in King Street …

The building was once the home of the Atlas Insurance Company.

The clock at the church of St Edmund King and Martyr in Lombard Street sports a delicate, pretty crown (EC3V 9EA) …

This is Throgmorton Street at the turn of the last century, straw hats (or boaters) being clearly in fashion. You’ll find a short history of them here…

The clock on the left is still there (EC2N 2AT) …

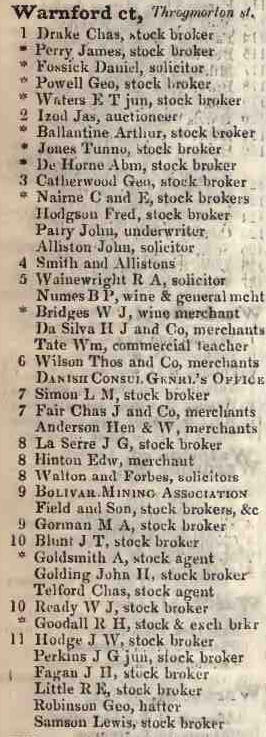

You’ll see that Warnford Court was rebuilt in 1884 but, out of interest, I did a bit more research and came across this list of the tenants in 1842 …

Stock brokers, solicitors and merchants mainly but also a hatter, a ‘commercial teacher’, an auctioneer and, strangely, the Danish Consul General’s Office. Interestingly, the Bolivar Mining Association was also located there. The Association was formed to work copper mines at Aroa, Venezuela and were owned for some time by the Bolivar family who leased them to an English company to help finance the war of independence. You can read more here.

Fleet Street has a lot to offer when it comes to clock spotting.

How about this masterpiece …

Installed just after the Great Fire of London in 1671, it was the first clock in London to have a minute hand, with two figures (perhaps representing Gog and Magog) striking the hours and quarters with clubs, turning their heads whilst doing so.

The present version of the clock was installed in 1738 before, in 1828, being moved to the 3rd Marquess of Hertford’s house in Regent’s Park. The Great War saw the Regent’s Park residence housing soldiers blinded from combat. The charity which undertook this went on to name itself after where the clock in the house came from: St Dunstan’s. It was returned to the Church in 1935 by Lord Rothermere to mark the Silver Jubilee of King George V. You can read a lot more about its history here.

If you like the occasional burst of colour, look up at this Art Deco treat, also in Fleet Street outside the old offices of the Daily Telegraph (EC4A 2BB) …

I am really pleased to report that the refurbishment of Bracken House is now complete and we can see again the extraordinary Zodiacal clock on the side of the building that faces Cannon Street (EC3M 9JA).

Here it is in all its glory …

If you look more closely at the centre this is what you will see …

On the gilt bronze sunburst at the centre you can clearly make out the features of Winston Churchill. The building used to be the headquarters of the Financial Times and is named after Brendan Bracken, its chief editor after the war.

During the War Bracken served in Churchill’s wartime cabinet as Minister of Information. George Orwell worked under Bracken on the BBC’s Indian Service and deeply resented wartime censorship and the need to manipulate information. If you like slightly wacky theories, there is one that the sinister ‘Leader’ in Orwell’s novel 1984, Big Brother, was inspired by Bracken, who was customarily referred to as ‘BB’ by his Ministry employees.

The oddly-shaped Blackfriar pub on Queen Victoria Street displays a pretty clock just above the jolly friar’s head …

Unfortunately it hasn’t worked for long time.

This wise old owl looks across the road to the north side of London Bridge, observing the thousands of commuters flowing back and forth every day from London Bridge Station (although not so many lately!). He is perched outside what was once the offices of the Guardian Royal Exchange Insurance Company (later just ‘Guardian’) and was for a while their symbol, presumably signifying wisdom and watchfulness.

Rising from the flames and just about to take off over the City is the legendary Phoenix bird and from 1915 until 1983 this was the headquarters of the Phoenix Assurance Company at 5 King William Street. One can see why the Phoenix legend of rebirth and restoration appealed as a name for an insurer (EC4N 7DA).

The clock shows the name of the present tenants, Daiwa Capital Markets.

Before clocks there were, of course, sundials and there are many fine examples in the City – both old and relatively new.

These are my two favourites …

The Jacobean church of St Katharine Cree in Leadenhall Street was built between 1628 and 1630 and survived the Great Fire of 1666. On the south wall is this wonderful dial, circa 1700, which is described as having ‘gilded embellishments including declining lines, Babylonian/Latin hours and Zodiac signs’. Its Latin motto Non Sine Lumine means Nothing without Light.

And this dial in Fournier Street …

It was once a Protestant church, then a Methodist Chapel, next a Jewish synagogue and is now the Brick Lane Mosque (E1 6QL).

In the late 17th century some 40-50,000 French Protestants, known as Huguenots, fleeing persecution in France, arrived in England with around half settling in Spitalfields. They started a local silk-weaving industry and, incidentally, gave us a new word ‘refugee’ from the French word réfugié, ‘one who seeks sanctuary’. They flourished and established this church in 1743 naming it La Neuve Eglise (The New Church) and installed the sundial we can see today. The Latin motto Umbra sumus translates as ‘we are shadow’, and is taken from Horace’s statement Pulvis et umbra sumus, meaning ‘We are dust and shadow’.

You can read more about city sunduals in my blog called, appropriately, We are but shadows.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …

https://www.instagram.com/london_city_gent