Although I love my City expeditions, every now and again it’s nice to explore further afield and, for some reason, with me this usually means heading east. On this occasion I took the DLR to Limehouse and walked south.

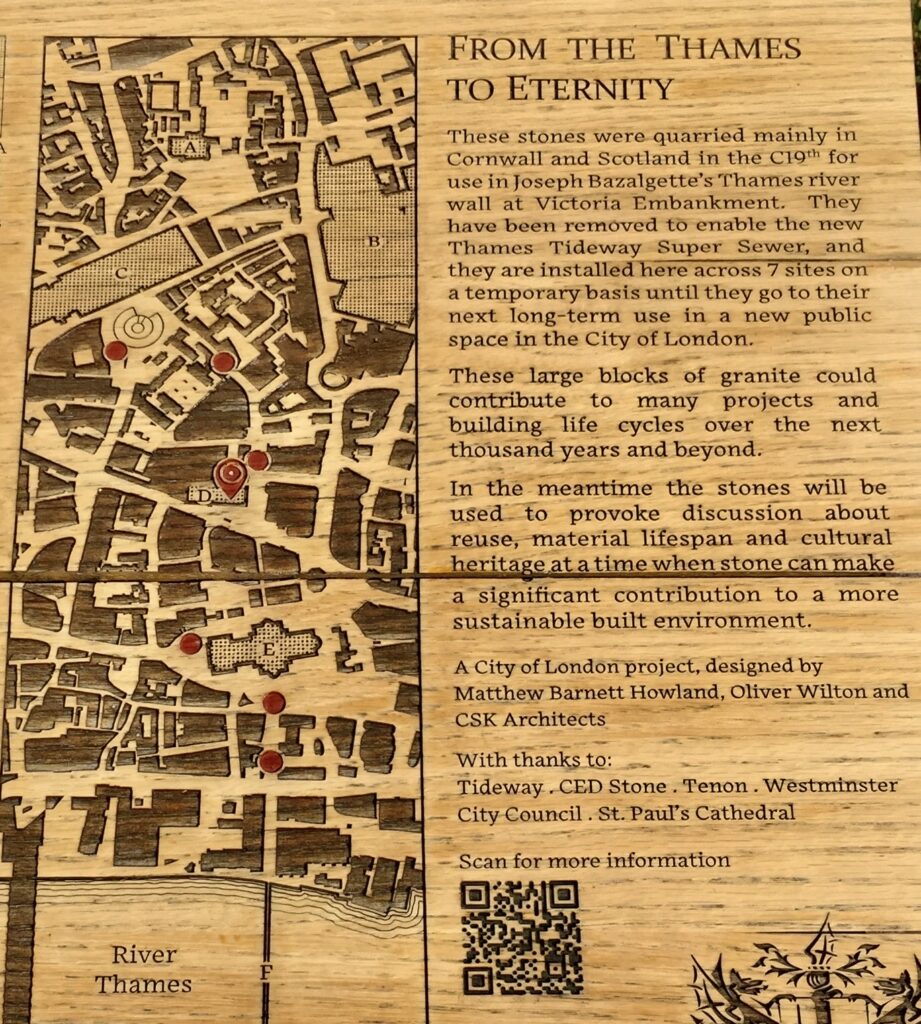

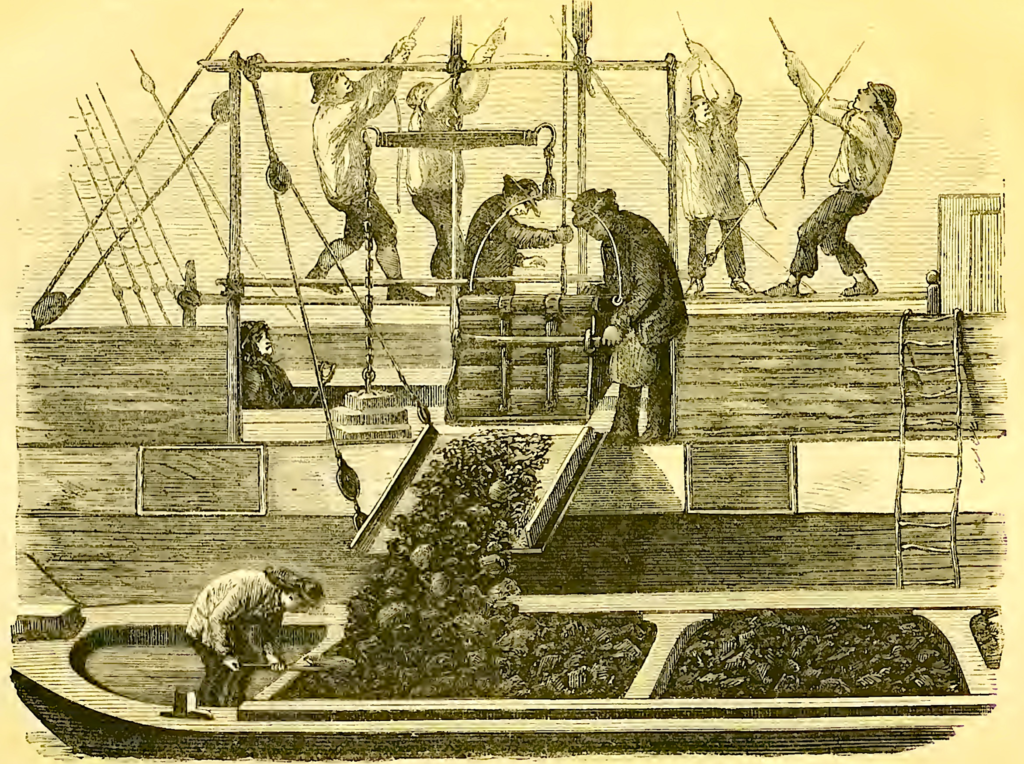

On the way I passed Limehouse Basin, a navigable link between the Thames and two of London’s canals. First dug in 1820 as the eastern terminus of the new Regent’s Canal, it was gradually enlarged in the Victorian era and incorporated a lock big enough to admit 2,000 ton ships. The basin in 1827 …

Here coal was unloaded from ships to barges and until 1853 it was done entirely by human muscle power. Working in total silence, a nine-man gang was expected to unload 49 tons of a coal a day but, according to Henry Mayhew, they often achieved double that amount. During each period each rope man climbed a total distance of nearly 1 1⁄2 vertical miles — and sometimes more. This system was known as ‘whipping’ …

Congestion in the 1820s …

Congestion in the 2020s …

Instead of slaving shifting coal, people here are more likely to be slaving at nearby Canary Wharf.

Nice to see a bit of greenery …

Some horticultural humour …

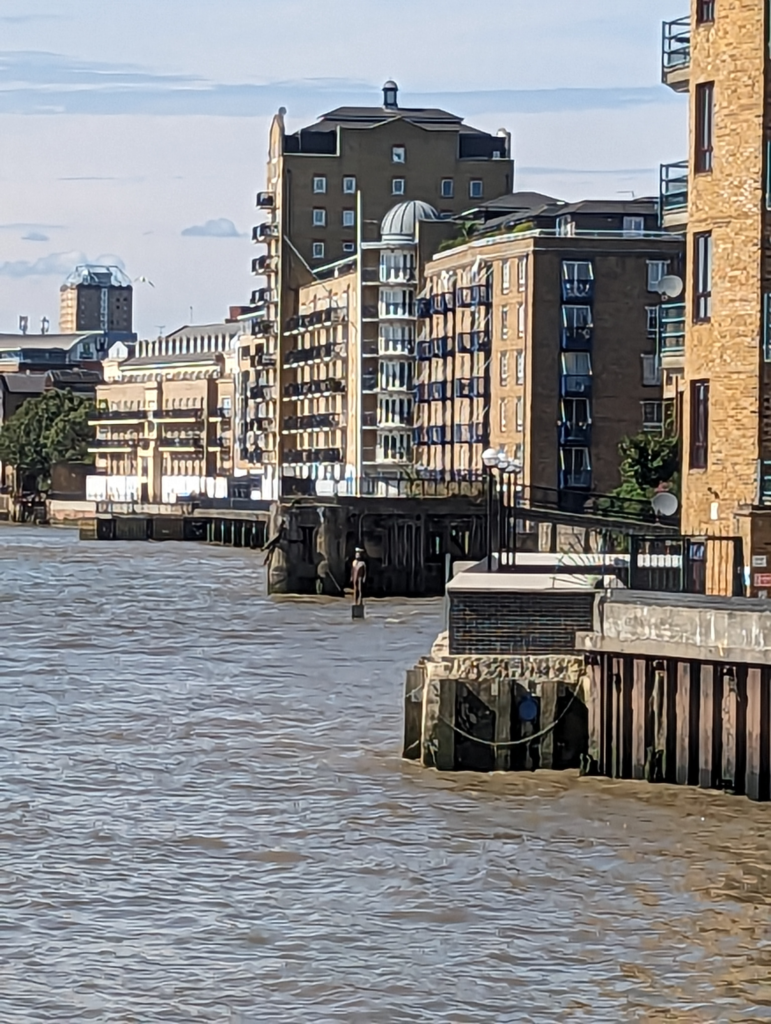

Onward to Narrow Street, so known because once upon a time it was … er … very narrow.

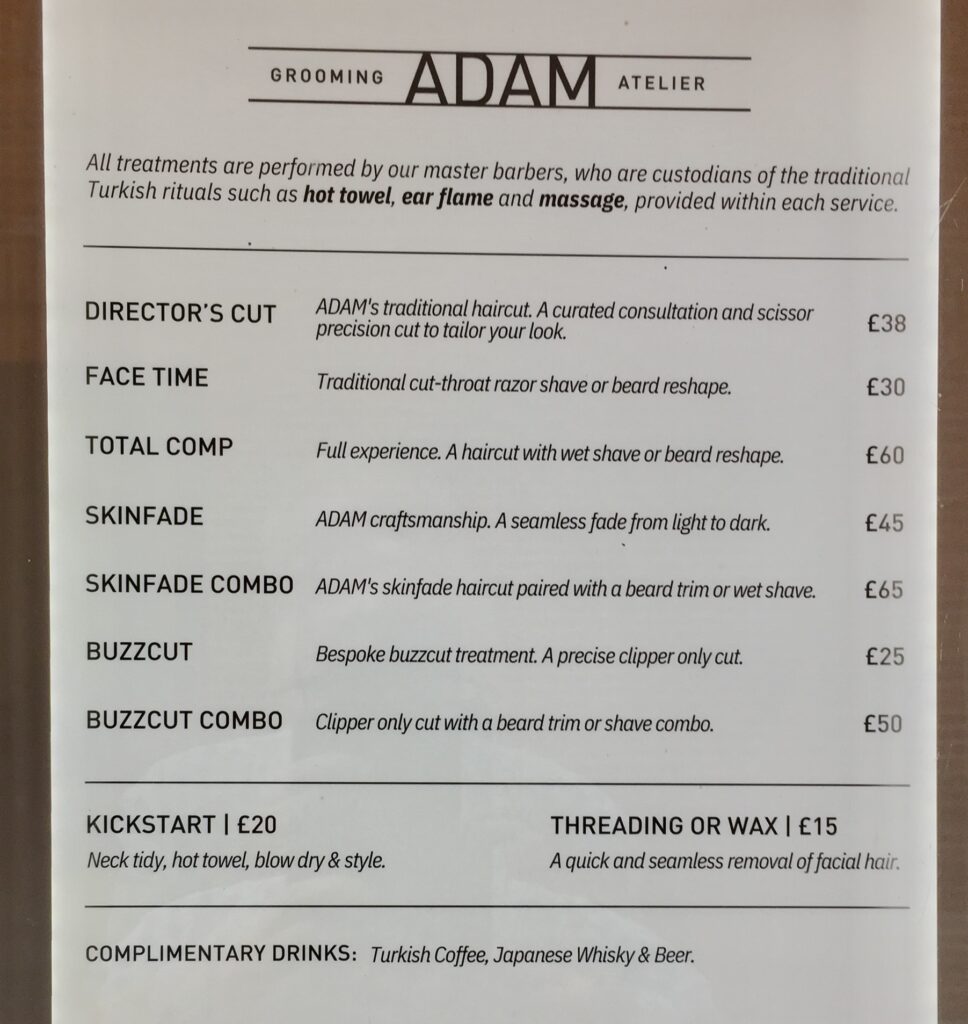

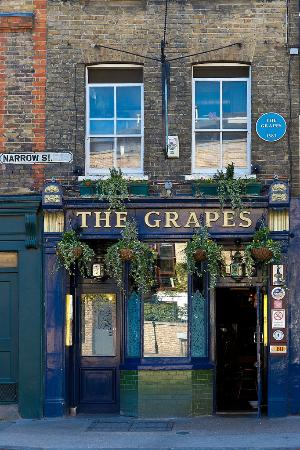

Time to stop for a bit of refreshment …

The pub is partly owned by Sir Ian McKellen and has a really atmospheric ‘old boozer’ interior …

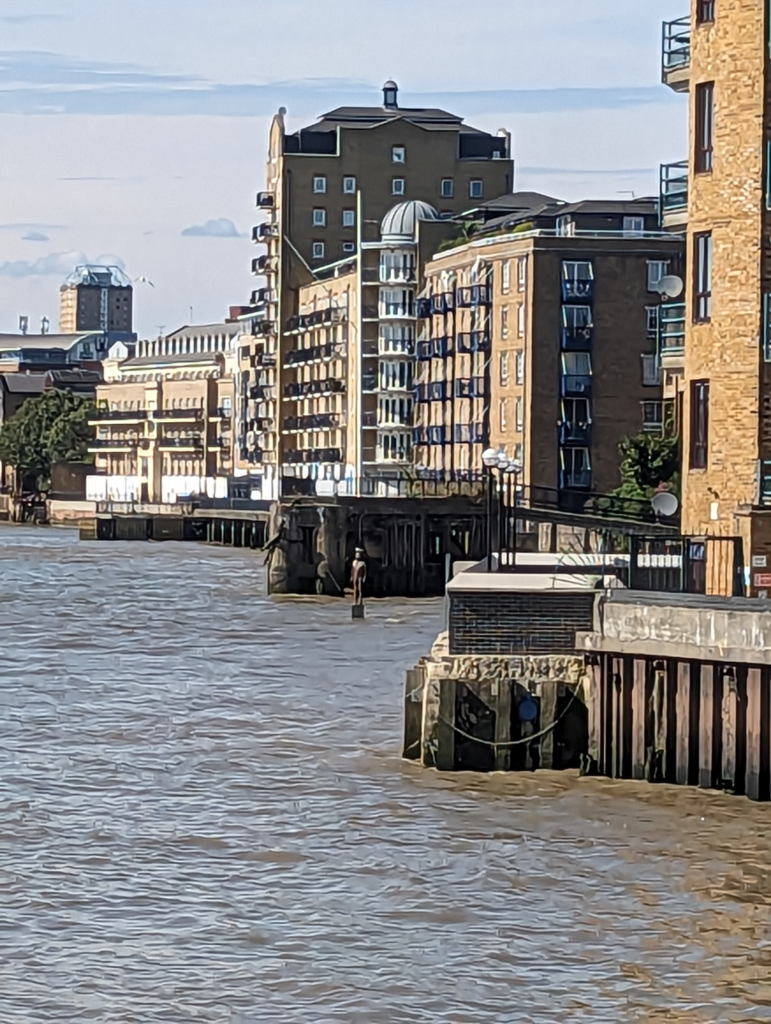

The terrace outside overlooks the Thames and from it you can see this mysterious life-sized figure …

It’s a sculpture by Anthony Gormley and is one of a series entitled Another Time. The artist describes the series as follows: Another Time asks where the human being sits within the scheme of things. Each work is necessarily isolated, and is an attempt to bear witness to what it is like to be alive and alone in space and time.

The seagulls have shown it little respect but he can be thankful that this one, perched just across the road, isn’t capable of flying …

You can see The Grapes in the background …

The sculpture was commissioned by the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1994 and stands in Ropemaker Fields, the park taking its name from the fact that rope was once manufactured in this district. The work by the artist Jane Ackroyd is mixed media in that the bronze figure of the gull is actually standing on a coil of rope.

The man from further east along the river …

Images from Dunbar Wharf …

The poor Gherkin can now only be clearly seen from the east …

Dunbar Wharf was named after the Dunbar family who had a very successful business at Limekiln Dock. The family wealth was initially from a Limehouse brewery established by Duncan Dunbar. It was his son, also called Duncan, who used the money he inherited from his father to build the shipping business that was based at Dunbar Wharf. The company’s ships carried passengers and goods across the world as well as convicts to Australia. The wharf, probably in the 1950s, showing lighters with cargo moored alongside …

Limekiln Dock …

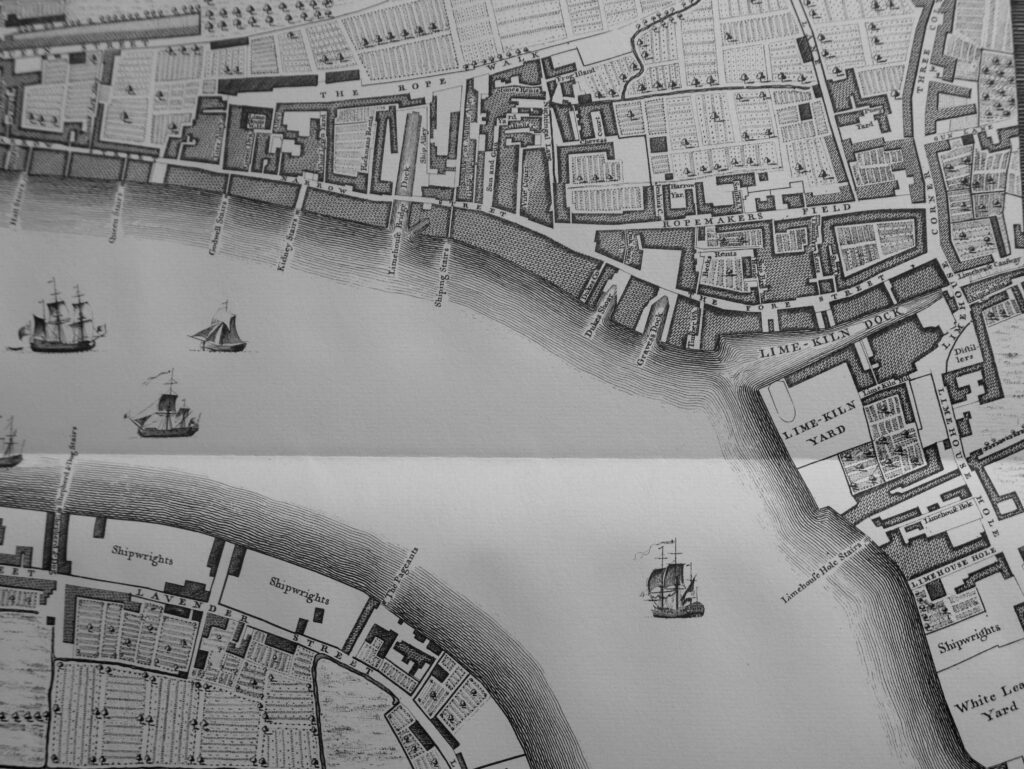

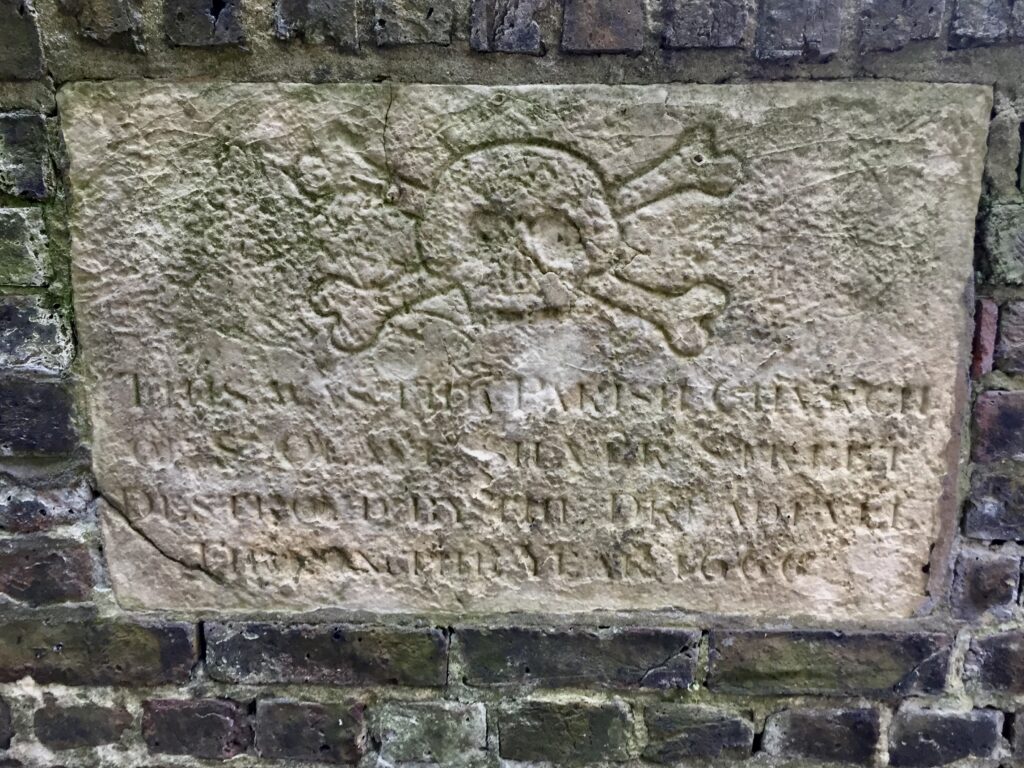

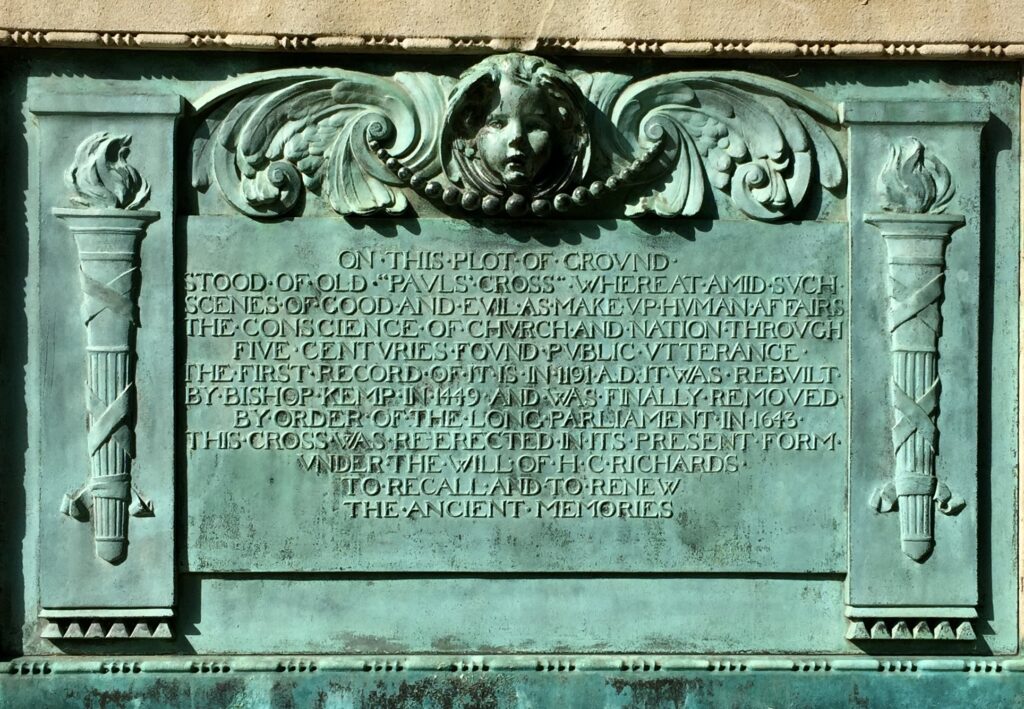

This dock is a very old feature in the area. In the following Rocque map extract from 1746, the dock is to the right …

Rocque shows that on the southern side of the dock entrance was Lime Kiln Yard. This was the location of the lime kilns that as well as giving their name to the dock, were also the origin of the name Limehouse.

And finally, at the South Eastern tip of Millwall, near Canary Wharf, lie the remains of a great ship’s launch ramp …

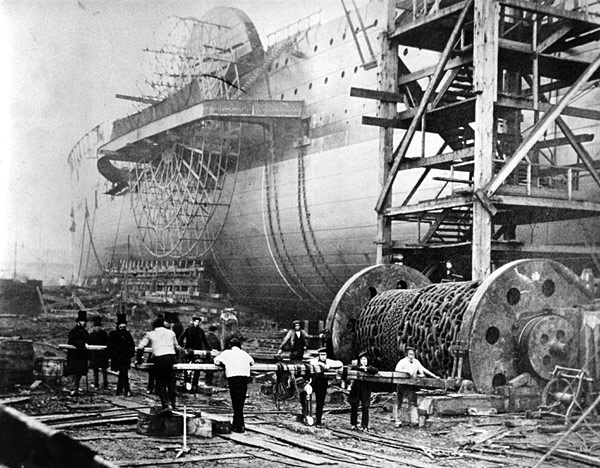

SS Great Eastern was an iron sail-powered, paddle wheel and screw-propelled steamship designed by Iaambard Kingdom Brunel and built by John Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the Thames. She was the largest ship ever built at the time and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling.

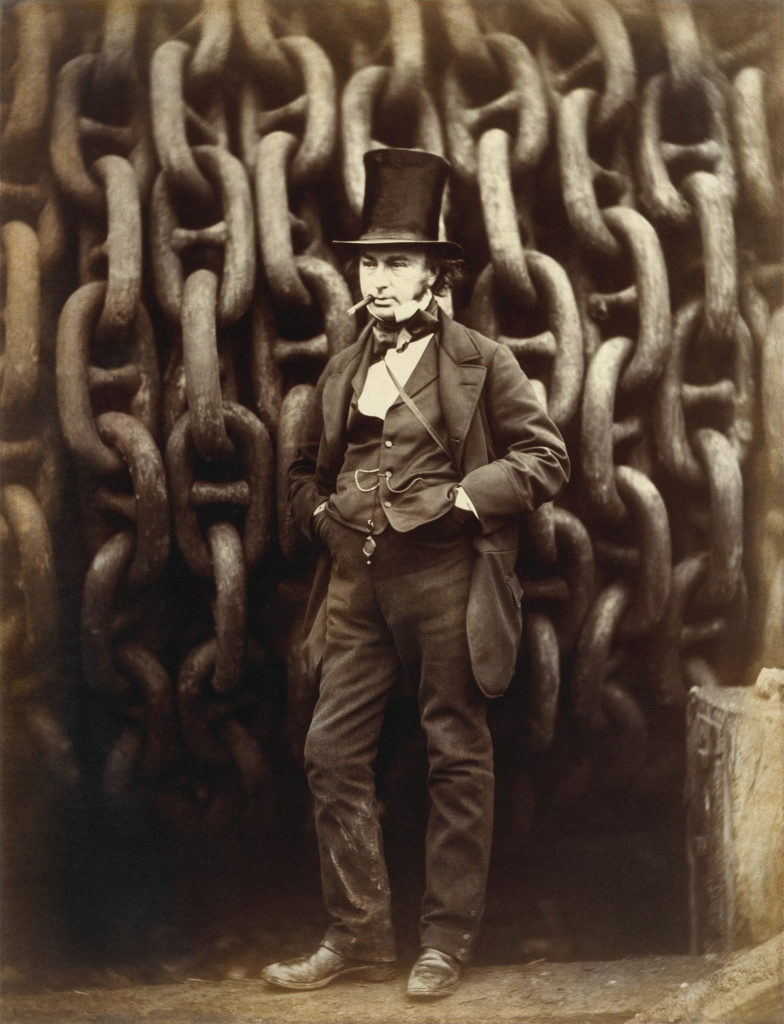

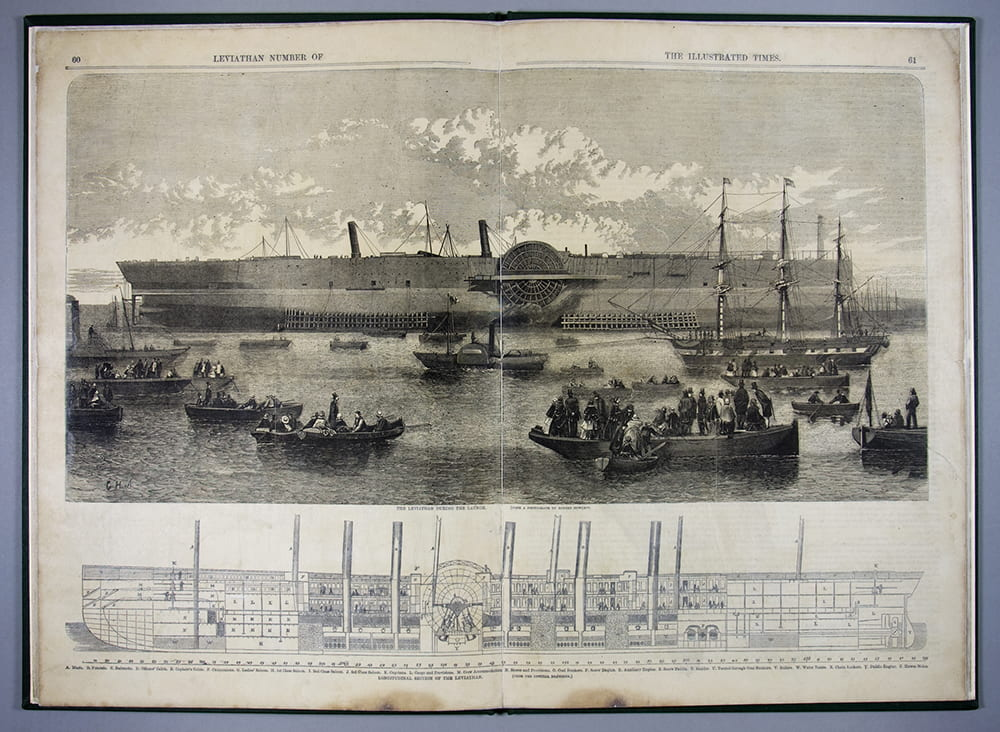

Her launch was planned for 3 November 1857 but ship’s massive size posed major logistical issues and, according to one source, the ship’s 19,000 tons made it the single heaviest object ever moved by humans! Since no dock was big enough, Brunel’s solution was to launch the ship sideways using cables and chains. Nothing had been attempted on this scale before, but Brunel was confident that his calculations were correct to allow the launch to go ahead.

This is the famous photograph by Robert Howlett of Brunel in front of the ship’s launching chains …

The ship under construction …

Because Brunel knew the launch would be fraught with difficulty he was keen to keep the whole thing low-key, however the ship company sold thousands of tickets for the launch and every available vantage point was taken on land as well as on the river.

The launch, however, failed, and the ship was stranded on its launch rails – in addition, two men were killed and several others injured, leading some to declare Great Eastern an unlucky ship. Over the next few days various investigations were carried out to determine why the ship did not move, and in the end it was decided that the steam winches were simply not up to the job of pulling the vessel into the Thames. In fact, it took another three attempts and three months to finally get the ship into the water on 31 January the following year.

Throughout the construction of the ship, Brunel kept letter-books, six large volumes into which every piece of correspondence sent or received regarding the Great Eastern was copied. These volumes are an amazing resource, effectively detailing the entire progress of the project and illuminating many of Brunel’s thought processes and his relationships with colleagues and suppliers. See this link to the University of Bristol Library.

Tragically, Brunel suffered a stroke just before Great Eastern‘s maiden voyage in 1859, in which she was damaged by an explosion. He died 10 days later, aged 53, leaving an extraordinary pioneering legacy behind him.

The ship berthed in New York in 1860 …

Read all about this great ship and its rather sad end here.

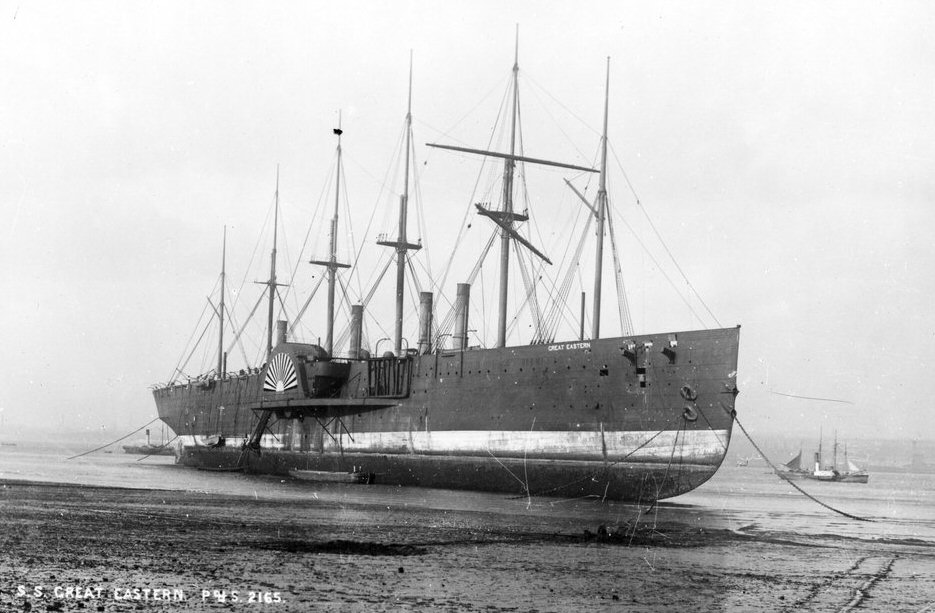

Beached, prior to being broken up …

Once again I am extremely grateful to the London Inheritance blogger for much of the historical information contained in this week’s blog.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …