Whenever I am travelling anywhere by plane or train I am always ludicrously early and that was the case last week when I was catching a train at Waterloo. I therefore took the opportunity to look around and see if there was some material for the blog. There certainly was.

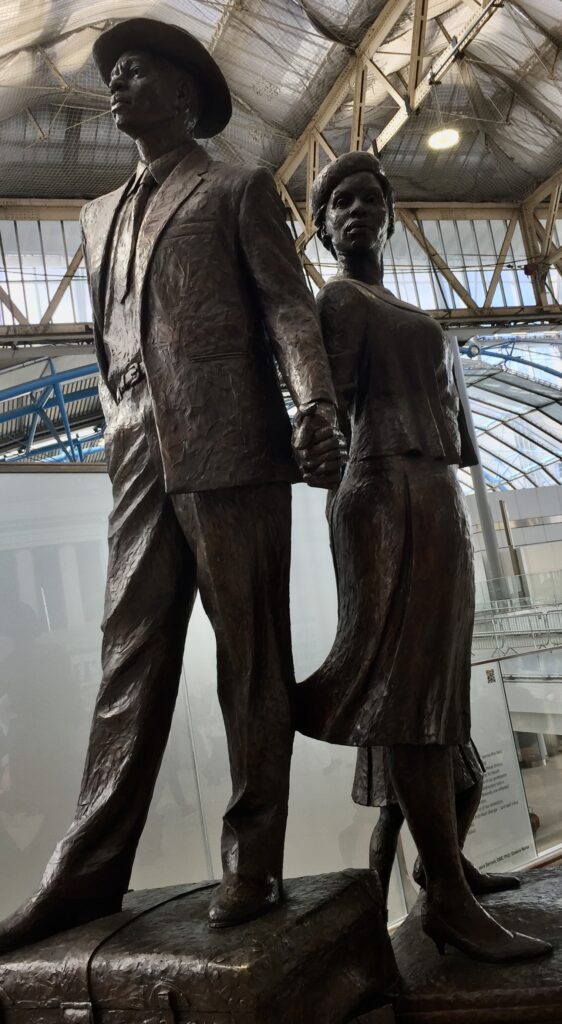

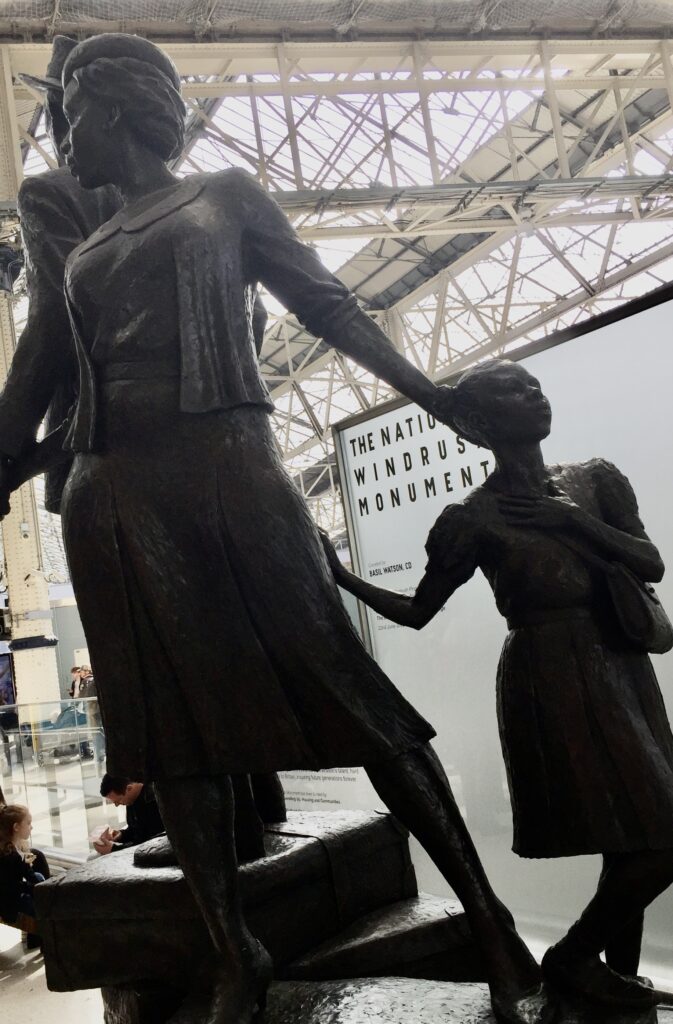

The station now hosts the National Windrush monument, designed by renowned Jamaican artist Basil Watson. It acknowledges and celebrates the Windrush generation’s outstanding contribution and has been created as a permanent place of reflection, to foster greater understanding of the generation’s talent, hard work and continuing contribution to British society.

The three figures – a man, woman, and child – dressed in their ‘Sunday best’ are climbing a mountain of suitcases together, demonstrating the inseparable bond of the Windrush pioneers and their descendants, and the hopes and aspirations of their generation as they arrive to start new lives in the UK.

There’s much more to see at Waterloo and I shall return to it next week and write more about these images …

My Waterloo research has led me to write about a very different type of station that operated nearby. Passengers departing from here were destined for eternity rather than the seaside.

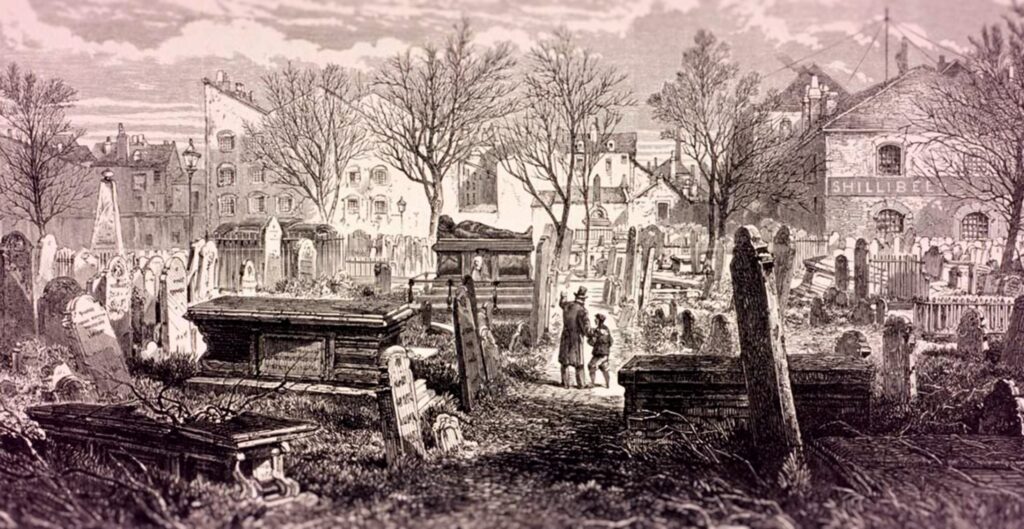

In the first half of the 19th century, London’s population shot up from around a million people in 1801 to close on two and a half million by 1851. Death was commonplace in the 19th century and eventually the City’s churchyards were literally full to bursting. Coffins were stacked one atop the other in 20-foot-deep shafts, the topmost mere inches from the surface. Putrefying bodies were frequently disturbed, dismembered or destroyed to make room for newcomers. Disinterred bones, dropped by neglectful gravediggers, lay scattered amidst the tombstones; smashed coffins were sold to the poor for firewood. Clergymen and sextons turned a blind eye to the worst practices because burial fees formed a large proportion of their income.

This is Bunhill Burial Ground around that time …

You can also get some idea of how packed cemeteries were if you look at some of the existing City churchyards and observe how much higher the graveyards are compared to street level. This, for example, is the graveyard of St Olave Hart street as seen from inside the church …

Between 1846 and 1849, a devastating cholera epidemic swept across London resulting in the deaths of almost 15,000 Londoners and it became apparent that something had to be done.

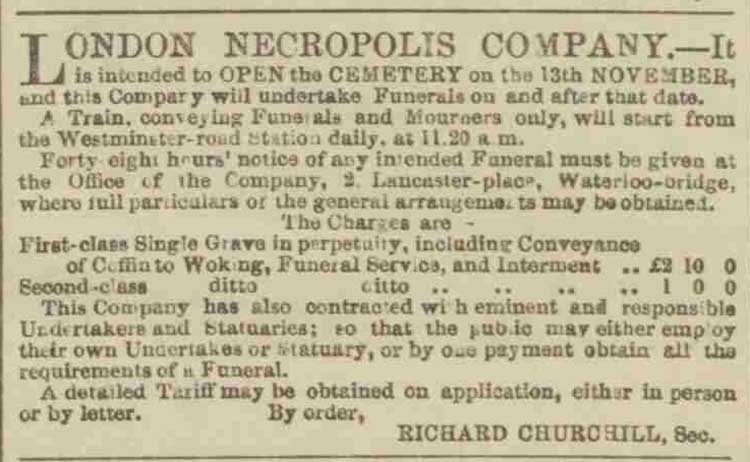

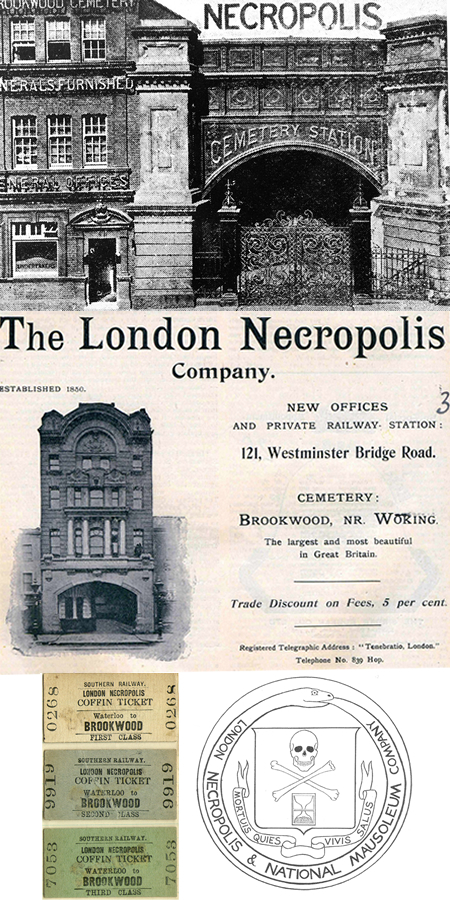

Legislation proved ineffective but private enterprise stepped in and a series of huge cemeteries, in which Londoners could be laid to rest in lush, green spacious landscapes, sprang up outside the metropolis. One such enterprise was the grandly titled ‘London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company’ (LNC), which was formed in July, 1852, with a mandate to develop the former Woking Common, at Brookwood, in Surrey, as one of the new cemeteries to serve London.

Carrying the deceased 23 miles by horse-drawn coach was obviously not practical and thus, in November, 1854, one of Britain’s most bizarre railway lines – the London Necropolis Railway – commenced operations, and daily trains were soon chuffing their way out of ‘Cemetery Station’ in Waterloo, ‘wending their way through the outskirts of London, and on through verdant woodlands and lush, green countryside outside the Metropolis, bound for the tranquil oasis of the new Valhalla in rural Surrey’.

The Company obviously gave a lot of thought to its logo and motto. Here it is (the skull and crossbones isn’t exactly subtle, is it) …

The Latin translates as ‘Peace to the dead, health to the living’. Possibly a reference to the lack of security in the old existing graveyards and also their threat to health. Just inside the circle is the ouroboros, an ancient symbol of a snake or serpent eating its own tail, variously signifying infinity and the cycle of birth and death.

The history of the company is an absolutely fascinating story and if you want to know more just click on the link here to the excellent London Walking Tours blog.

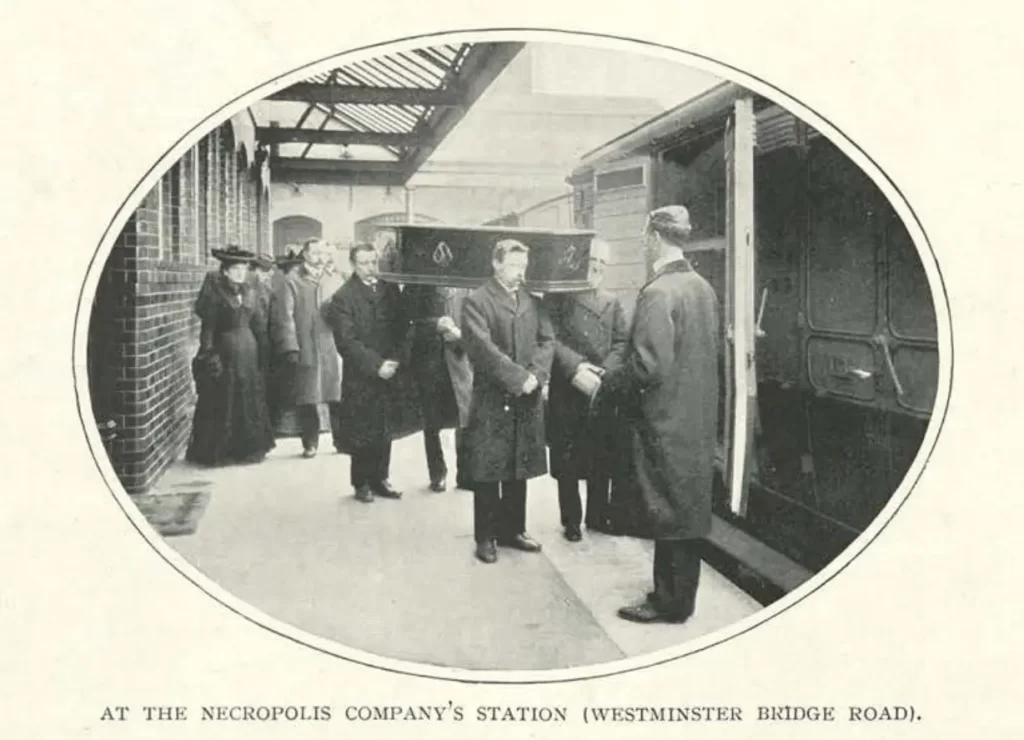

A new building for the London terminus was completed on the 8th of February, 1902. Here are some contemporary images …

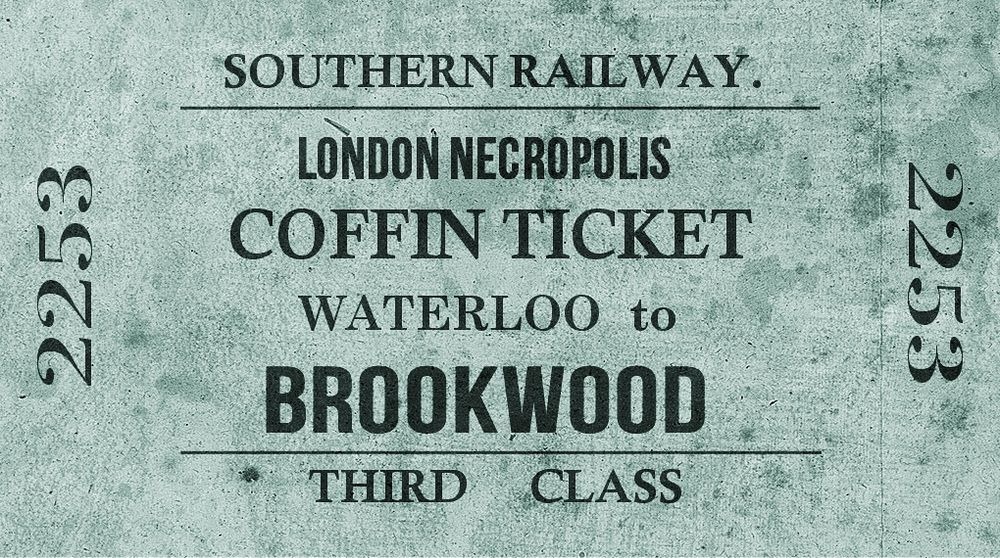

A class system operated. First and Second Class ‘passengers’, accompanied by mourners, were placed in the train first. Third class mourners were not allowed to witness their loved ones being loaded! …

The end of the line. A funeral train from Waterloo pulling into the north section station at the cemetery in the early 20th century …

On Friday, 11th April, 1941, the body of Chelsea Pensioner Edward Irish (1868 – 1941) left the London Necropolis Station en route for Brookwood. He was the station’s last customer.

Five days later, on the night of the 16th/17th of April, 1941, a German bombing raid on the area destroyed the company’s rolling stock, along with much of the building. The Southern Railway’s Divisional Engineer, having inspected the damage at 2pm, on April, 17th, 1941, reported starkly, ‘Necropolis and buildings demolished.’ Although the offices and the First Class entrance from Westminster Bridge Road had survived, the devastation effectively sounded the death knell for the Necropolis Railway, and, on the 11th of May 1941, the station was officially declared closed.

The First Class platform just after the bombing …

The site in 1950 …

By the time it was put out of business after 87 years the company had ferried over 200,000 bodies between Waterloo and Surrey.

The First Class entrance and the Company’s old offices on Westminster Bridge Road are still there today (SE1 7HR) …

Inside the entrance arch (I think those lamps may be part of the original building, they look suitably funereal) …

I caught this image as I walked home across Waterloo Bridge – the ever-changing City skyline …

Finally, by way of light relief, my favourite newspaper front page of the week – British journalism at its finest …

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …