I thought it might be interesting in these worrying days to look back on how one of my great heroes, Samuel Pepys, described the ferocious pestilence that attacked London’s citizens in 1665.

Pepys survived, and here he is a year later …

Hayls had already painted his wife and Pepys was so pleased he commissioned this one of himself. He noted in his diary on 17 March …

This day I begin to sit, and he will make me, I think, a very fine picture. He promises it shall be as good as my wife’s, and I sit to have it full of shadows, and do almost break my neck looking over my shoulder to make the posture for him to work by.

Pepys was a remarkable man, the son of a tailor whose rise to power owed something to circumstances but much more to his own tenacity, drive and personal charm. Despite eventually becoming First Secretary to the Admiralty (and instituting reforms that dramatically improved the professionalism of the Navy) it is for his diary that Pepys is usually remembered.

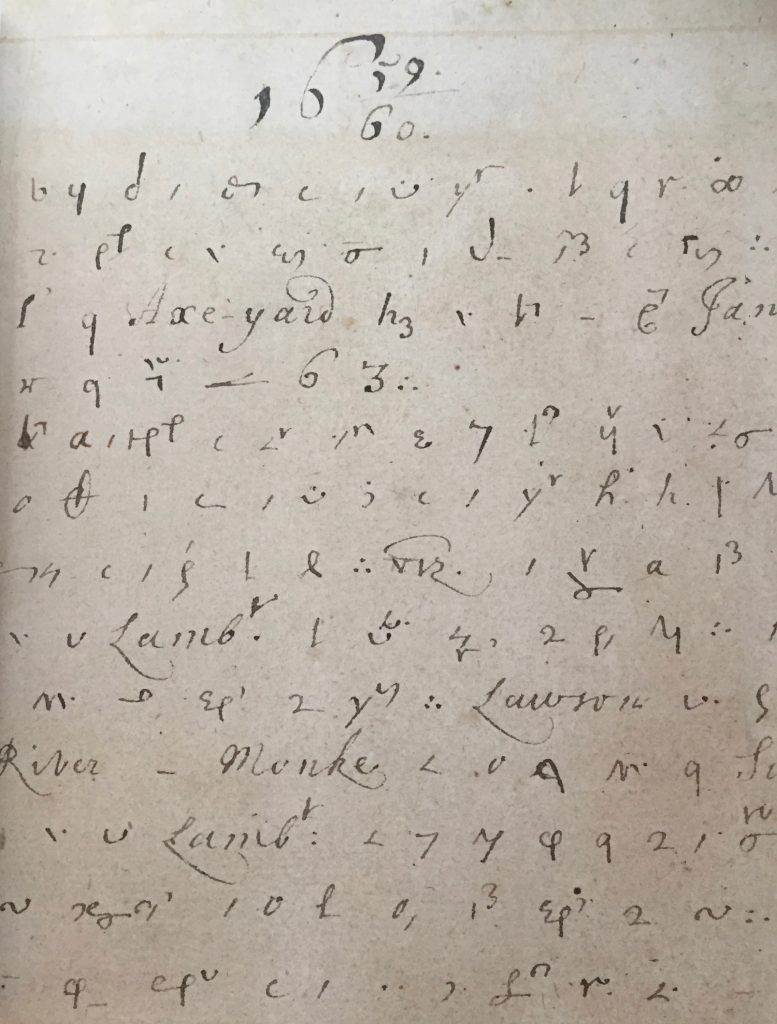

Here is its first page …

Written in a code and shorthand he personally devised, the diary runs to one and a quarter million words and covers the period 1660 to 1669. Anyone wanting to get a sense of the day-to-day life of an ambitious young Londoner, with a great appetite for work and pleasure, only has to consult his fascinating account.

But it is the year 1665 that I am going to write about.

The first mention in the diary of the plague was on 30 April 1665 …

Great fears of the sickness here in the City, it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all.

Then in July 1665 …

I did in Drury-lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there – which was a sad sight to me.

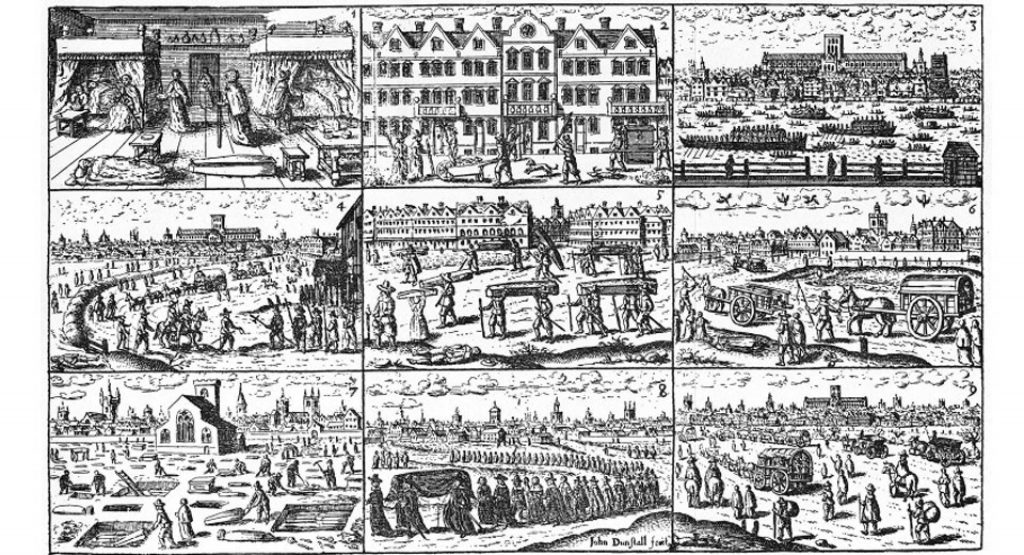

The main idea for management of the plague was containment of the infection and so entire families were locked in their own houses. A padlock was fixed to the outer door and a watchman assigned to make sure that any surviving inmates stayed there for the full 40-day quarantine period before being released. The only people being allowed to enter were the doctor, the nurse, the searchers and the men who came at night to remove the bodies …

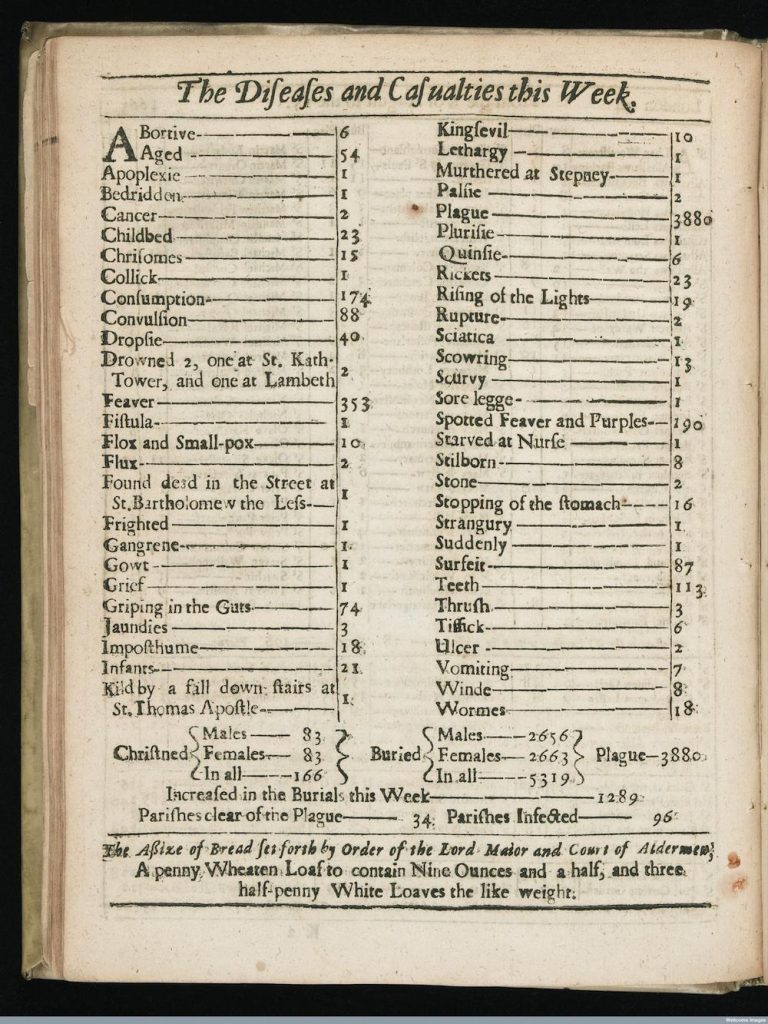

Who were the searchers? Deaths in London and their causes were recorded in the Bills of Mortality. These were usually collected and published by Parish Clerks and ‘searchers’ were employed to help collect the data. According to Dr Robin Gain of the Samuel Pepys Club …

Plague was almost certainly under-reported by the searchers, who were usually ignorant old women, paid by the parishes to go into the houses where people had died to ascertain the cause of death … If relations of plague victims could persuade or bribe the searchers to report a cause of death other than plague, the family might avoid being quarantined.

Here is the Bill of Mortality from 15 to 22 August 1665 held at the Wellcome Library London. You may find some of the reasons for death a bit surreal …

By 10 June Pepys reported that the plague had entered the City and on 26 July he wrote that the ‘sickness is got into our parish this week’. His parish was St Olave Hart Street.

The number of deaths were beginning to overwhelm the capacity of the City graveyards and plague pits were being opened up. Here is a further image from the Wellcome Collection …

On August 12th he wrote …

The people die so, that now it seems they are fain to carry the dead to be buried by daylight, the nights not sufficing to do it in.

One of the reasons I admire him so much is that because, unlike many of those who had the opportunity, Pepys remained in London for much of that year. Even after he and his employer were forced to relocate to Greenwich in the late summer, he commuted by river from there to his home in Seething Lane near the Tower of London and visited other parts of the capital.

There was a war going on at the time with the Dutch and Pepys believed he should stay at his post. Here is how he elegantly put it in a letter on 25 August to Sir William Coventry …

You, Sir, took your turn at the sword; I must not therefore grudge to take mine at the pestilence.

On the same day he wrote in his diary …

This day I am told that Dr. Burnett my physician is this morning dead of the plague … poor unfortunate man.

As plague moved from parish to parish Pepys described the changing face of London-life – ‘nobody but poor wretches in the streets’, ‘no boats upon the River’, ‘fires burning in the street’ to cleanse the air and ‘little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells’ that accompanied the burial of plague victims. He also writes in his diary about the desensitization of people, including himself, to the corpses of plague fatalities, ‘I am come almost to think nothing of it.’

It had eventually subsided significantly by January the following year and on January 30th 1666 he visited St Olave, but found the experience deeply shocking …

It frighted me indeed to go through the church … To see so many graves lie so high upon the churchyard, where many people have been buried of the plague.

And five days later, on February 4th he wrote …

It was a frost and had snowed last night, which had covered the graves in the churchyard, so I was less afraid of going through.

The churchyard survives, its banked-up top surface a reminder that it is still bloated with the bodies of plague victims, and gardeners still turn up bone fragments. Three hundred and sixty five were buried there including Mary Ramsay, who was widely blamed for bringing the disease to London. We know the number because their names were marked with a ‘p’ in the parish register.

In 1655 when he was 22 he had married Elizabeth Michel shortly before her fifteenth birthday. Although he had many affairs (scrupulously recorded in his coded diary) he was left distraught by her death from typhoid fever at the age of 29 in November 1669.

Do go into the church and find the lovely marble monument Pepys commissioned in her memory. High up on the North wall, she gazes directly at Pepys’ memorial portrait bust, their eyes meeting eternally across the nave where they are both buried. When he died in 1703, despite other long-term relationships, his express wish was to be buried next to her.

And the sculpture of Elizabeth – I think she looks beautifully animated, like she is in the middle of a conversation.

Another reason I like Pepys is that, despite the terrible events of 1665 he carried on his life as usual, no self-isolation for him. He still worked at the Navy Office, continued his adulterous liaisons, celebrated his cousin’s wedding, and pursued many of his interests. Surprisingly the year brought much opportunity and wealth Pepys’s way and, as the plague subsided, he wrote in his final diary entry for the year …

I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague-time.

According to the Bills of Mortality, 68,596 people died of the plague in London in 1665 but the true figure was probably more like 100,000. Even the lower figure represents a very high percentage of the population at the time, which was about 460,000. In today’s population that would mean getting on for 2,000,000 dead Londoners.

If you visit the church treat yourself to a copy of Dr Gain’s leaflet entitled Pepys and The Plague. It was of great help to me in composing this blog and can be yours for a modest £2 donation.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram :