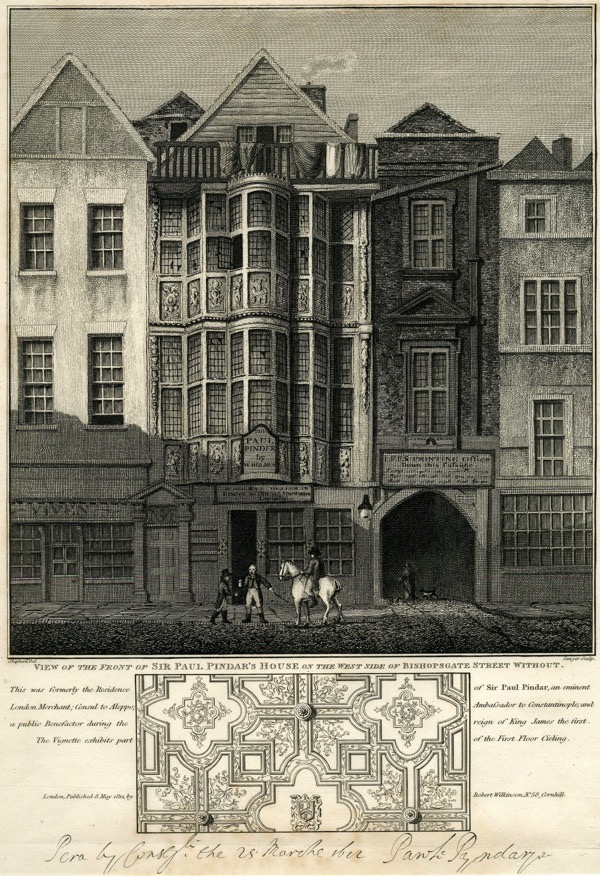

Just suppose you could go back in time and were approaching London from the north in Tudor times. If you were coming from modern day Lincoln or York, you would be following the old Roman Road, Ermine Street, which would lead you to Bishopsgate, one of the principal gates into the City. Stow’s 1598 Survey of London describes this area as part of the ‘suburbs without walls,’ and throughout the 16th century wealthy citizens were beginning to build properties for themselves in that vicinity. One of them was Sir Paul Pindar (1565?-1650), and when the Venetian Ambassador, Pietro Contarini, lodged with him in the early 17th century he described Bishopsgate Without as ‘… an airy and fashionable area … a little too much in the country‘.

It’s wonderful to know that you can today, in the 21st century, get some idea of the house’s scale and beauty since its facade is preserved and on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum …

Contarini’s chaplain described it as ‘a very commodious mansion which had heretofore served as the residence of several former ambassadors’.

Having unfortunately lent generously to Charles I, poor Pindar died leaving considerable debts and by 1660 the mansion had already been subdivided into smaller dwellings. It survived the Great Fire of 1666, but was soon given over to the London workhouse, with wards for ‘poor children’ and ‘vagabonds, beggars, pilferers, lewd, idle, and disorderly persons’. The street-level rooms on the front were used as a tavern, known as Sir Paul Pindar’s Head.

The house was demolished in 1890 to make room for the expansion of Liverpool Street Station, but we do have an idea as to what it looked like in 1812. There are more pictures and commentary on the Spitalfields Life blog which you can access here.

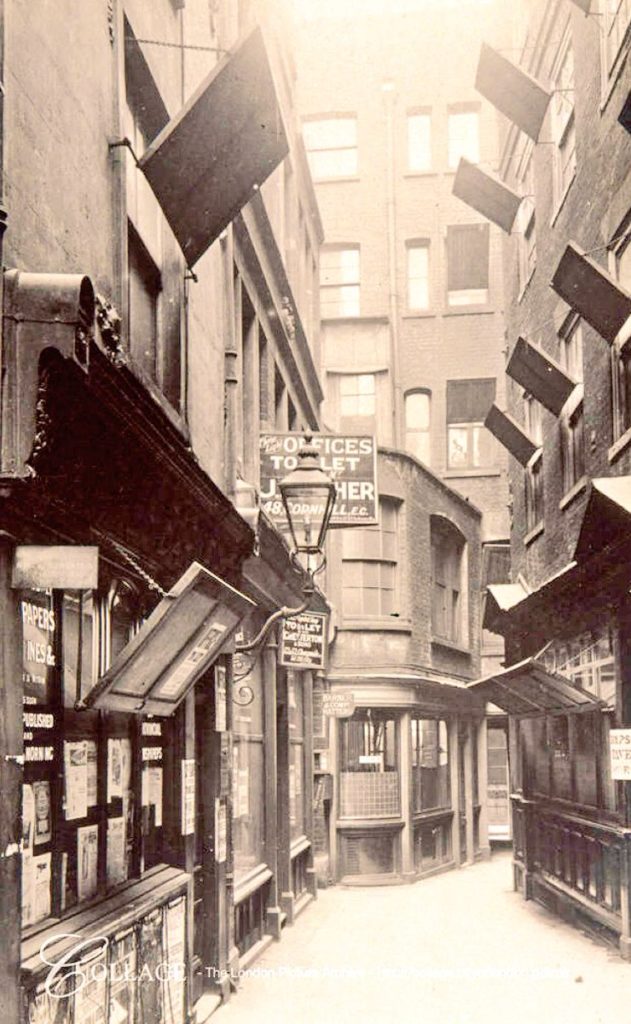

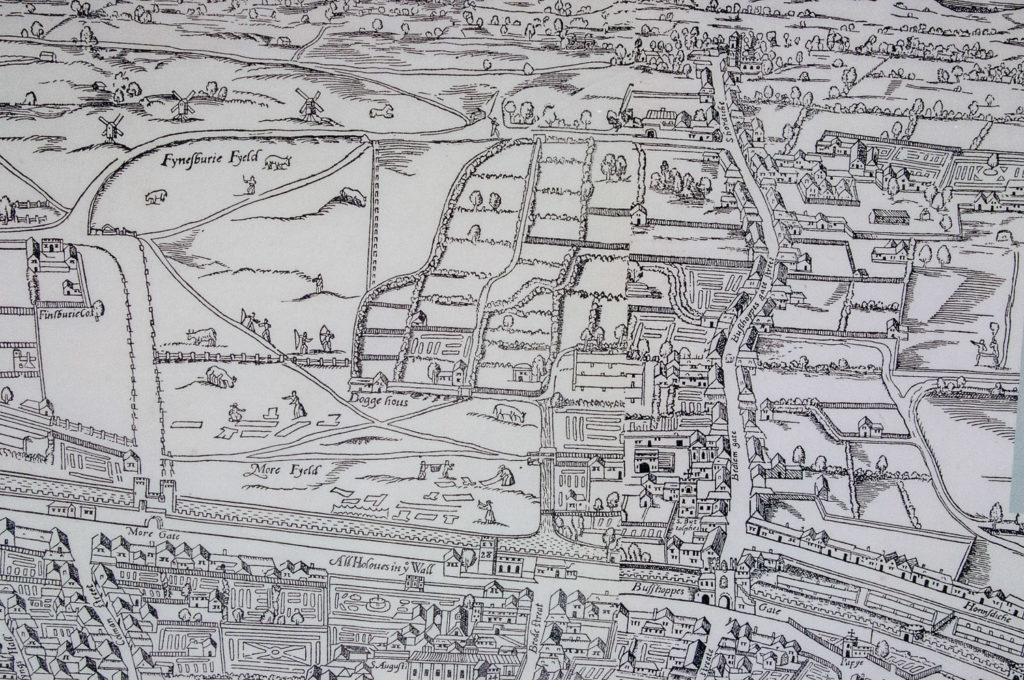

What would you see going on elsewhere in this area north of the City walls? We are extremely fortunate to have this map that gives us some idea …

This is one of the earliest maps we have of London and you can take an imaginary walk thanks to its fascinating detail. Approaching from Shoredich in the north, the already dissolved hospital of St Mary Spital would be on your left. On your right is the lunatic hospital of Bedlam before its destruction in the 1666 Great Fire. As you approached the Bishop’s Gate itself, the illustration appears to show some spikes exhibiting the gruesome remains of traitors who had been hanged, drawn and quartered. Moor Gate to the left seems to have a similar display and leads directly on to Moor Field, an area drained and ‘laid out in pleasant walks’ in 1527. There is a lot going on there.

Washing is being laid out to dry, goods are being carried to market, a lady carries a pot on her head, archery is being practised, people have stopped to chat and there is a rather elegant Dogge Hous. See if you can find the man with the horse and cart driving what looks like a sow and piglets in front of him.

To the right you can see that the wealthy and the religious orders have enclosed their land within private walls, windmills can be seen on hilly ground.

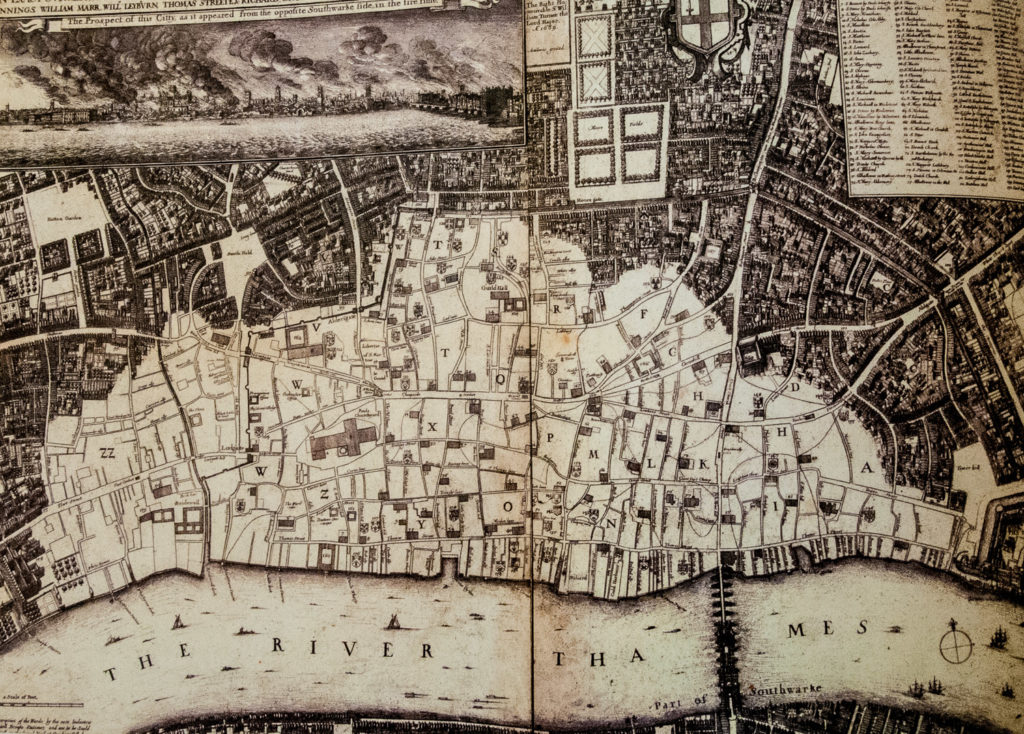

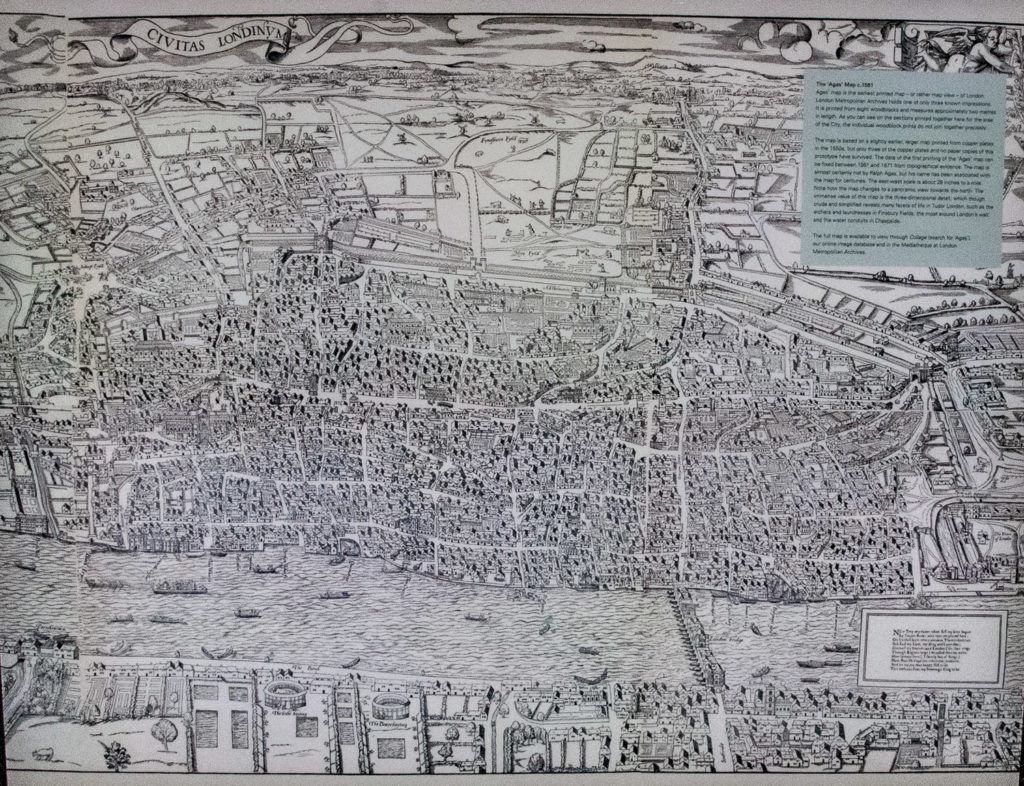

Now take a look at this map …

At a quick glance it looks the same but there are differences and this map is nowhere near as detailed. For example, fewer figures are shown in the fields and they are not so well drawn (the Dogge Hous is still there though!). Known as Civitas Londinum, it was first printed from woodblocks in about 1561 and obviously drew on the Copperplate map for much of its information. Widely, but erroneously, attributed to the surveyor Ralph Agas, no early copies survive and the small section above is from a modified version printed in 1633.

One of the things that fascinated me was how many of the streets exist to this day and have the same name. Here is another section of the map …

With some serious concentration I found Old Street, Chiswell Street, Beech Street, Cheapside, Aldersgate, Whitecross Street, Aldermanbury, Milk Street and a few others – all pretty much located exactly where they are today.

If you want to study an enlarged version of the map in more detail, pop into the Guildhall Art Gallery. Here it is displayed in all its glory …

The architect Simon Foxell, in his outstanding book Mapping London – Making Sense of the City, (ISBN 13: 9781906155070) states …

Civitas Londinum is the essential view into the teeming streets of Tudor London. It shows us the interrelationship between churches and streets and houses and how, outside the walls, London rapidly transforms into fields and villages. It shows the windmills that must have dominated the horizon and the regular lime kilns that must have filled the sky with smoke. A recognisable view into a past beyond living memory.

The Great Fire of 1666 devastated the City and, luckily for us, the etcher Wenceslaus Hollar was there to produce this ‘groundplot’ of the damage. His drawing of 1666 is a bird’s eye view of the City and gives us some perspective as to the vast extent of the catastrophe. The non-shaded area shows the extent of the destruction …

What else can we see today that pre-dates the Fire apart from the street names?

St Paul’s Cathedral was lost in the inferno but there was a remarkable survivor …

The effigy of John Donne, 17th century poet and Dean of the Cathedral, survived the Fire but you can still make out the scorch marks on the urn (you have to go into the Cathedral to see it). I have written about Donne in an earlier blog which you can access here.

And finally, there is the oldest house in the City …

Built in 1615, it survived the Great Fire due to its being enclosed and protected by the priory walls of St Bartholomew. Incidentally, you’ll notice the building has no window sills. The post-Fire Building Acts required window sills at least four inches deep or more to be installed in homes in order to reduce the risk of fire spreading upwards. I have written about this and other City dwellings in an earlier blog City Living.

I hope you enjoyed this trip back in time. I love old maps, so will probably be exploring the history of the City in a similar way in the future.