Today I am writing about two people who changed the world of newspaper reporting forever, and both have commemorative busts in Fleet Street.

They come from the great days of newspaper publishing, when Fleet Street throbbed with sound of the press machinery and journalists and barristers gossiped at the bar in El Vino. ‘They used to say that the way to tell them apart was to ask if anyone had a pen’, says Michael McCarthy, a former reporter, ‘the journalists would be the ones who didn’t have one.’

El Vino is still there at 47 Fleet Street, but the family that had owned it since 1879 sold up in 2015

Ladies were forced to sit in the back room until Anna Coote, a journalist who was banished in this way, took the owners to court. In 1982, three Appeal Court judges, all of whom admitted to being patrons, ordered that the ban be lifted on the grounds that the exclusion could harm women’s careers if they could not ‘pick up the gossip of the day’. The manager at the time called it ‘a very sad day’ for El Vino, ‘a place where old-fashioned ideals of chivalry still flourish’.

At number 78 Fleet Street is this bust, erected in 1936, with a stirring inscription on a plaque below that reads …

T. P. O’Connor, journalist & parliamentarian, 1848 – 1929.

His pen could lay bare the bones of a book or the soul of a statesman in a few vivid lines.

As well as being a journalist, Thomas Power O’Connor (often referred to as ‘Tay Pay’, people mimicking the way he pronounced his initials) was also an Irish nationalist and House of Commons MP for almost 50 years. One biographer has claimed that ‘there is hardly one significant paper circulating in the English speaking world that does not owe something of its style to T.P.’s original Star‘. He ‘made newspapers both clean and readable’ and therefore ‘popular’.

He founded the Star in 1880. Its editorial policy pulled no punches and declared …

The rich, the privileged, the prosperous need no guardian or advocate; the poor, the weak, the beaten require the work and word of every humane man and woman to stand between them and the world.

It was a radical evening paper published six days a week, fighting valiantly against social injustice and for the rights of the poor as well as workers involved in trade union disputes. So popular was it that by 1888 it had achieved an average circulation of some 125,000 copies a day at a price of one halfpenny.

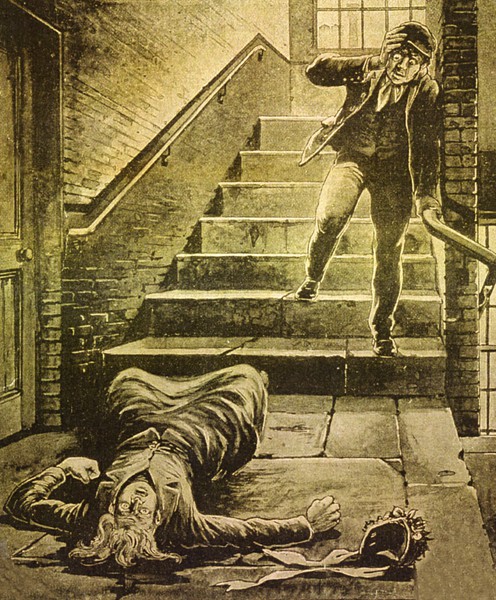

O’Connor also understood that sensational crimes sold newspapers and the ‘Whitechapel murders’ gave plenty of scope – graphic details being often accompanied by lurid illustrations, for example …

‘Finding the body of Martha Tabram’

Reporting on what would later be described as the Jack the Ripper murders pushed circulation up to over 400,000, and reports were accompanied by harsh criticism of the police and the Commissioner Charles Warren in particular.

The Star finally ceased publication in 1960, absorbed by its long-time rival the Evening News which became the Evening News and Star, reverting back to just the Evening News in 1968.

The T.P. tradition was followed by others. When, in 1896, Alfred Harmsworth, later lord Northcliffe, launched his new journal the Daily Mail he was said to have instructed his journalists :

Find me a murder every day!

He now looks down at us from the wall of St Dunstan’s-in-the-West at 186 Fleet Street …

The bust is by Kathleen Scott, Baroness Kennet. An inscription below reads: ‘Northcliffe MDCCCLXV-MCMXXII’ (1865-1922)

The Daily Mail was immensely popular – two of its taglines were:

‘The busy man’s daily journal’ and ‘The penny newspaper for one halfpenny’

Prime Minister Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury, was less flattering, describing it as …

Produced by office boys for office boys

The original plan was to sell 100,000 copies but the print run on the first day was 397,215 and additional printing facilities had to be acquired to sustain a circulation which rose to 500,000 in 1899. By 1902, at the end of the Boer Wars, circulation was over a million, making it the largest in the world.

The paper devised numerous ways to keep their readership engaged. For example, in 1906, the paper offered £1,000 for the first flight across the English Channel and £10,000 for the first flight from London to Manchester. Punch magazine thought the idea preposterous and offered £10,000 for the first flight to Mars, but by 1910 both the Mail‘s prizes had been won.

Along with his other newspapers (including the Observer, Evening News, Times and Daily Mirror) by 1914 Northcliffe controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation. All his papers were fiercely imperialistic and anti-German and in the run up to the war, the Star thundered in criticism …

Next to the Kaiser, Lord Northcliffe has done more than any living man to bring about the war

Such was Northcliffe’s influence on anti-German propaganda that, on 14th February 1917, a German warship shelled his house, Elmwood, in Broadstairs in an attempt to assassinate him. He escaped injury, but the shells killed the gardener’s wife and small child.

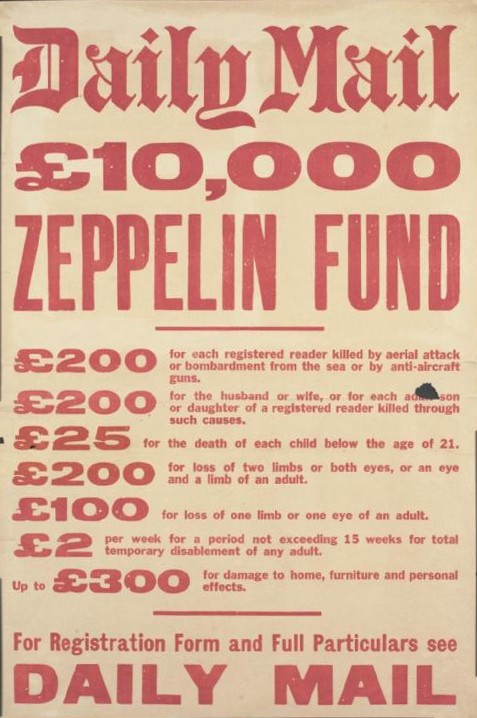

Incidentally, direct selling insurance off the page is nothing new. During the First World War the paper sold insurance against Zeppelin attacks …

Harmsworth’s marriage to Mary Elizabeth Milner in 1888 produced no children but he had four acknowledged children by two different women. The first, Alfred Benjamin Smith, was born when he was seventeen, the mother being a sixteen-year-old maidservant in his parents’ house. Smith died in 1930, allegedly in a mental home. By 1900, Harmsworth had acquired a new mistress, an Irishwoman named Kathleen Wrohan, about whom little is known but her name. She bore him two further sons and a daughter, and died in 1923.

When he himself died in 1922 he left three months’ pay to each of his six thousand employees.

The Daily Mail’s print circulation in January this year was 1,343,142, second only to the Sun at 1,545,594, but Mail Online is claimed to be the most widely read English newspaper in the world. Its slogan is ‘Seriously Popular’ – I think both O’Connor and Northcliffe would have approved of that aspiration at least (not sure what they would have made of the content though!).