Ten years ago a detailed analysis of the population of the City of London revealed that, with the number of residents at 9,185, the City had the second smallest residential population of any English Local Authority with the exception of the Isles of Scilly!

Just to put this into even greater perspective, before the Great Fire of 1666 the population estimate was 80,000 of whom about 70,000 lost their homes in the conflagration. The Fire created an unprecedented opportunity to rebuild the City and proposals were speedily produced by eminent people such as Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke and John Evelyn. In Wren’s case, he imagined a reconstructed capital full of wide boulevards and grand civic spaces, a city that would rival Paris for Baroque magnificence

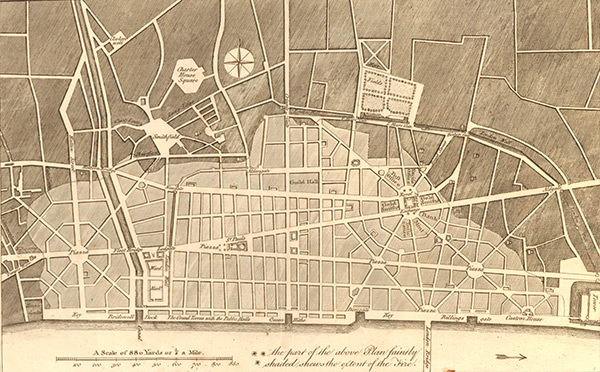

Christopher Wren’s plan for rebuilding London © Trustees of the British Museum

None of the plans were implemented – defeated by the sheer complexity of revoking existing freeholds, renegotiating leases and the likely cost of compensation. Post-fire, some streets were widened and new legislation was introduced requiring buildings to be more fire resistant.

‘No man whatsoever shall presume to erect any house or building great or small, but of brick or stone’.

1667 Rebuilding Act

By mid-1667 surveyors were already at work designating boundaries and meticulously marking out building plots. Interfering with these markers was discouraged by the threat of imprisonment or ‘being taken to the place of his offence and there whipped until the body be bloody‘.

By 1688 it is estimated that between 12,000 and 15,000 buildings had been rebuilt and London was being enhanced further by the 51 new churches designed by Wren plus, of course, the construction of a new St Paul’s cathedral.

In my latest walk around the City I have been looking for residential buildings that have survived despite redevelopment, the Blitz and, in one case, the Great Fire of London itself.

Cloth Fair was named in honour of the medieval festival Bartholomew Fair where merchants gathered to buy and sell material. The Poet Laureate and conservationist John Betjeman moved into number 43 in 1955 and his residency is commemorated with a blue plaque. Nearby at number 41/42 is the oldest house in the City. Built in 1615, it survived the Great Fire due to its being enclosed and protected by the priory walls of St Bartholomew. The building was originally part of a larger scheme of eleven houses featuring a courtyard in the middle, known as ‘The Square in Launders Green’ – the original site of the priory laundry.

Incidentally, you’ll notice the building has no window sills. The post-Fire Building Acts required window sills at least four inches deep or more to be installed in homes in order to reduce the risk of fire spreading upwards.

41/42 Cloth Fair

1 and 2 Laurence Pountney Lane are a remarkable survival from the early 18th century. They were built in 1703 as a pair of red brick, four-storey houses, on the site of a single post-fire house. They are considered to be finest surviving houses of this period in the City with elaborately carved foliage friezes around the doors and cornice above and ornate shell-hoods over the doorways. The virtuosity of the woodwork is explained by the fact that the houses were built by a master carpenter, Thomas Denning. He had worked on Wren’s church of St Michael Paternoster Royal nearby and would later contribute to Hawksmoor’s St Mary Woolnoth. Like other ambitious craftsmen, Denning branched out into the cut throat world of speculative building. At Laurence Pountney Hill he appealed to the market by ingeniously contriving two basements beneath the houses. This created an abundance of storage space that would be attractive to the London merchants, whose houses doubled as business premises. Denning’s speculation paid off; on 15 July 1704 he sold both houses to Mr John Harris for £3,190, a tidy sum.

1 & 2 Laurence Pountney Hill

The delightful doorway hoods. Look closely – the cherubs on the right are playing bowls!

Here is a close-up (you may have to concentrate – they are not always obvious)

The date still visible despite years of over-painting

Numbers 27 and 28 Queen Street are a pair of mid-18th century houses set back behind a forecourt. They are some of the finest examples of their type in the City, with their elevated position giving them an additional prominence.

27 and 28 Queen Street

If you look at this picture of 41 Crutched Friars below you will see the entrance arch to a narrow thoroughfare on the right. This is French Ordinary Court – named for the fact that in the 17th century the Huguenots were allowed by the French Ambassador, who had his residence at number 41, to sell coffee and pastries there. They also served fixed price meals and in those days such a meal was called an ‘ordinary’. The lane itself dates from the 15th century and perhaps even earlier. It was further enclosed in the 19th century as the railway station was constructed above, transforming it into a cavernous passage. French Ordinary Court was commonly known as ‘Spice Alley’ until the late 20th century, the smells lingering from the old warehouses nearby – something I can attest to personally since I frequently used it as a short cut in the 1970s and 80s.

The French Ambassador’s residence until the 18th century

Dr Johnson’s cat Hodge looks towards their old home. Once surrounded by the throbbing printing presses of Fleet Street newspapers, Gough Square is today a quiet haven off the noisy main road. Now known as Dr Johnson’s House, 17 Gough Square was built by one Richard Gough, a City wool merchant, at the end of the seventeenth century. It is the only survivor from a larger development and Dr Johnson lived here from 1748 to 1759 whilst compiling his famous dictionary.

Dr Johnson’s House in Gough Square

Amen Court is a private enclave of houses occupied by the Canons of St Paul’s Cathedral. Given its name by a former processional route of the clergy, the court consists of a range of three houses of the 1670s along with six Queen Anne Revival houses dated 1878-80, the group unified by the use of red bricks. In his flat here in January 1958, Canon John Collins started the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Amen Court – note the nice original ironwork including ‘snuffers’ for extinguishing lighted torches

Part of the Chiswell Street Conservation Area, these buildings are a fine example of terraced town houses dating from the late 18th Century and built for the then burgeoning middle classes in London. A plaque on number 43 tells us that numbers 43 to 46 were rebuilt in 1774 after a fire in 1773 and restored in 1988. There is an attractive wooden sundial in the adjacent courtyard which reference the fire.

Often referred to as the ‘Whitbread Brewery Partners’ Houses’

The inscriptions read: ‘Such is Life’, and, around the sides, ‘Built 1758, burnt 1773, rebuilt 1774’

The curiously named Wardrobe Place, just off Carter Lane, is a tranquil spot and marks the location of what was once the King’s or Royal Wardrobe. In the 1360s the executors of the late Sir John Beauchamp sold his house here to King Edward III for the storage of his ceremonial robes which were then transferred from the Tower of London. In addition, the Wardrobe held garments for the whole royal family for all state occasions, together with other furnishings and robes for the King’s ministers and Knights of the Garter. In his diary, Pepys records visiting it in order to borrow appropriate Court dress. The facilities were gradually extended to comprise stables, courtyard warehouse, workrooms, great hall, chapel, treasury, kitchens and chambers.

Beauchamp’s house was destroyed in the Great Fire and in 1673 a Crown lease was granted to William Wardour, who redeveloped the site with houses arranged around an open courtyard. The north and east sides were begun in 1678. Wardrobe Court, as it was known until the late 18th century, was described in John Strype’s Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (1720) as ‘a large and square court with good houses’.

Wardrobe Place

Ghost sign in Wardrobe Place – ‘Snashall & Son – Printers, Stationers & Account Book Manufacturers – 1st Door on (?)’

I couldn’t write about homes without mentioning this great man, George Peabody (1795-1869)

George Peabody by W.W.Storey 1867-69

Here he sits, looking pretty relaxed, at the northern end of the Royal Exchange Buildings. Born in Baltimore he became extremely wealthy importing British dried goods and, after visiting frequently, became a permanent London resident in 1838. In retirement he devoted himself to charitable causes setting up a trust, the Peabody Donation Fund, to assist ‘the honest and industrious poor of London’. The Peabody Trustees would use the fund to provide ‘cheap, clean, well-drained and healthful dwellings for the poor’ with the first donation being made in 1862.

My ‘local’ estate is the one on Whitecross Street and dates from 1883 – the design is very typical Peabody, with honey coloured bricks and a pared down Italianate style.

Block E, which survived the Blitz

Resident planting

Peabody now own and manage over 55,000 homes across 29 London boroughs as well as Kent, Sussex and Essex. Do browse their website – the section on the Trust’s history is particularly interesting.