If you get the chance, do visit the Guildhall Art Gallery to see The Big City exhibition. It’s superb, and admission is ‘pay what you can’. The challenge of finding the mice was keeping kids (and adults) very amused during my visit! More about that later.

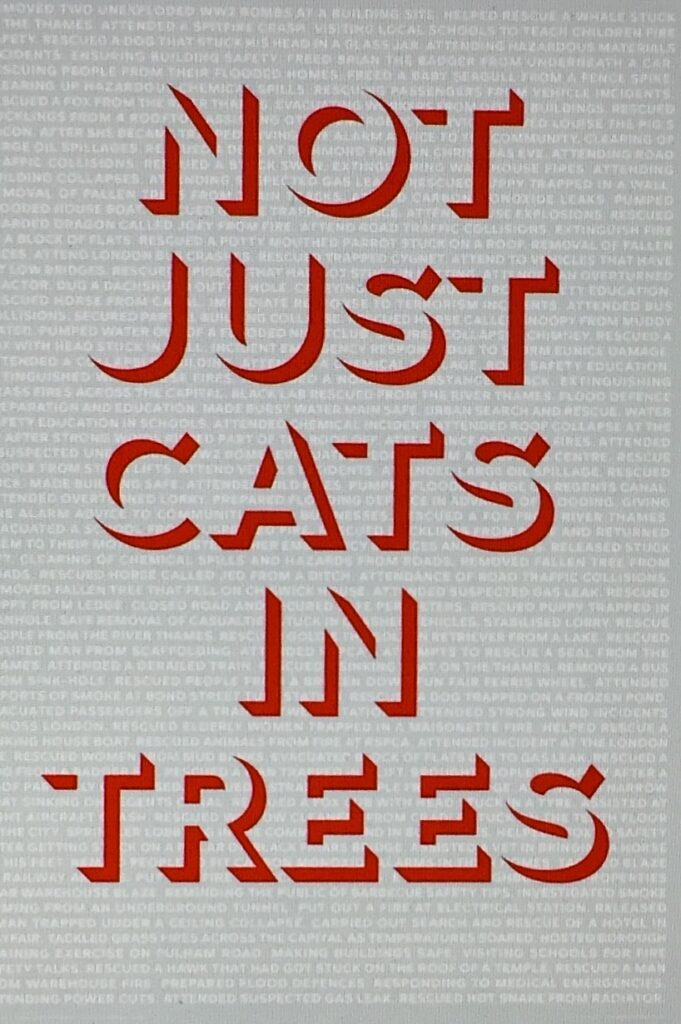

Here’s my personal selection, starting with City Streets.

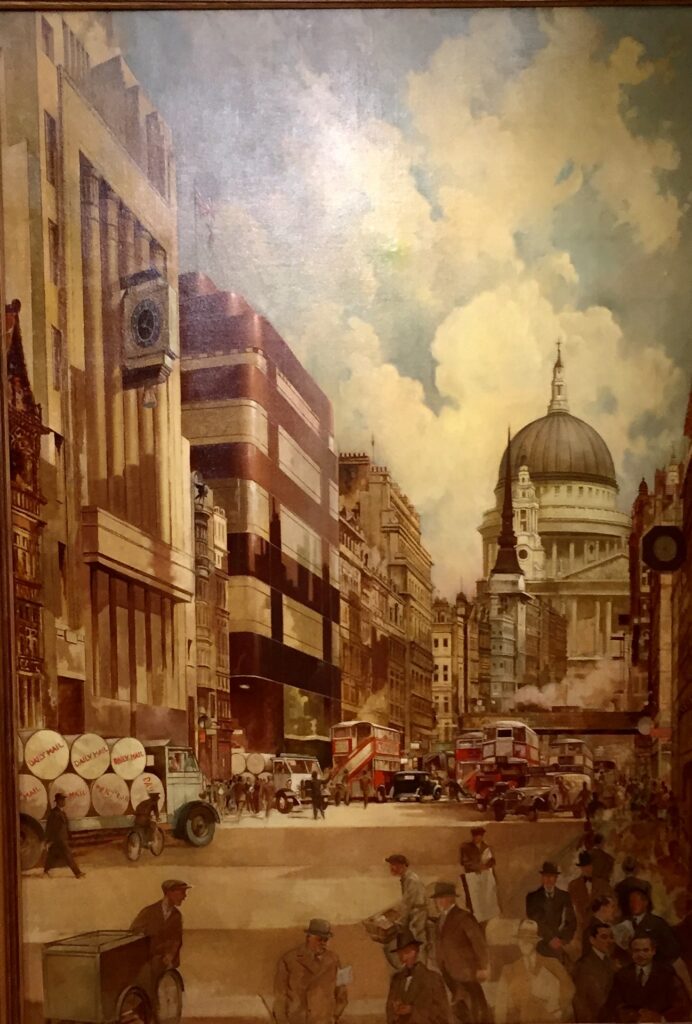

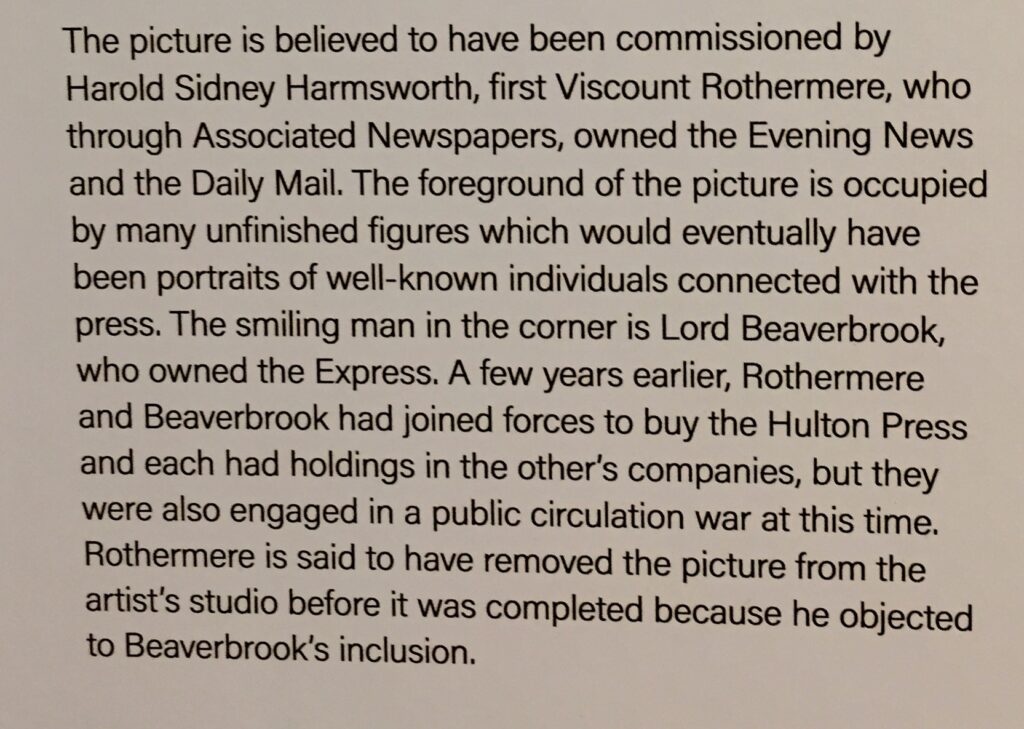

This picture of Fleet Street in the 1930s is by an unknown artist and has a fascinating back story …

If you look at the characters in the foreground you’ll see that the picture is unfinished. Why is this? The label puts forward a suggestion …

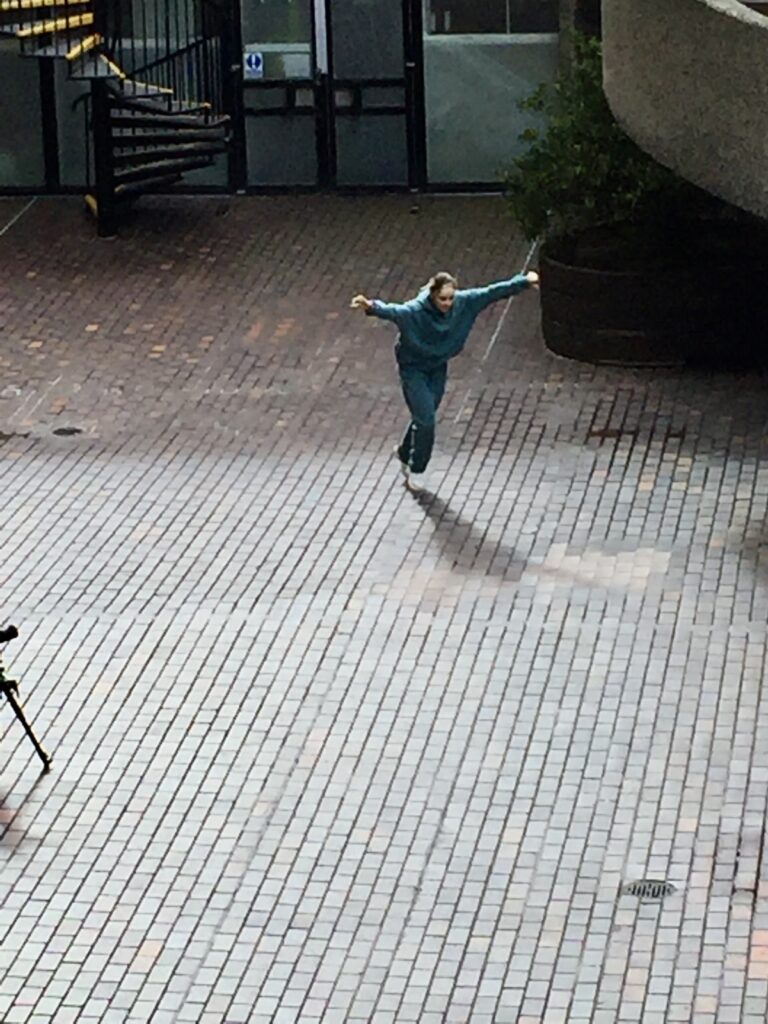

The pedestrian crossing outside Barbican Tube station …

And now some pageantry …

Suffering from severe arthritis and unable to climb the St Paul’s Cathedral steps, the Queen remained in her coach, so the short service of thanksgiving was held outside the building. Some amazing old film footage has survived and you can view it here and here.

This is a more intimate picture of City pageantry and its participants (with some splendid beards on display) …

Can you recognise the characters in this little group …

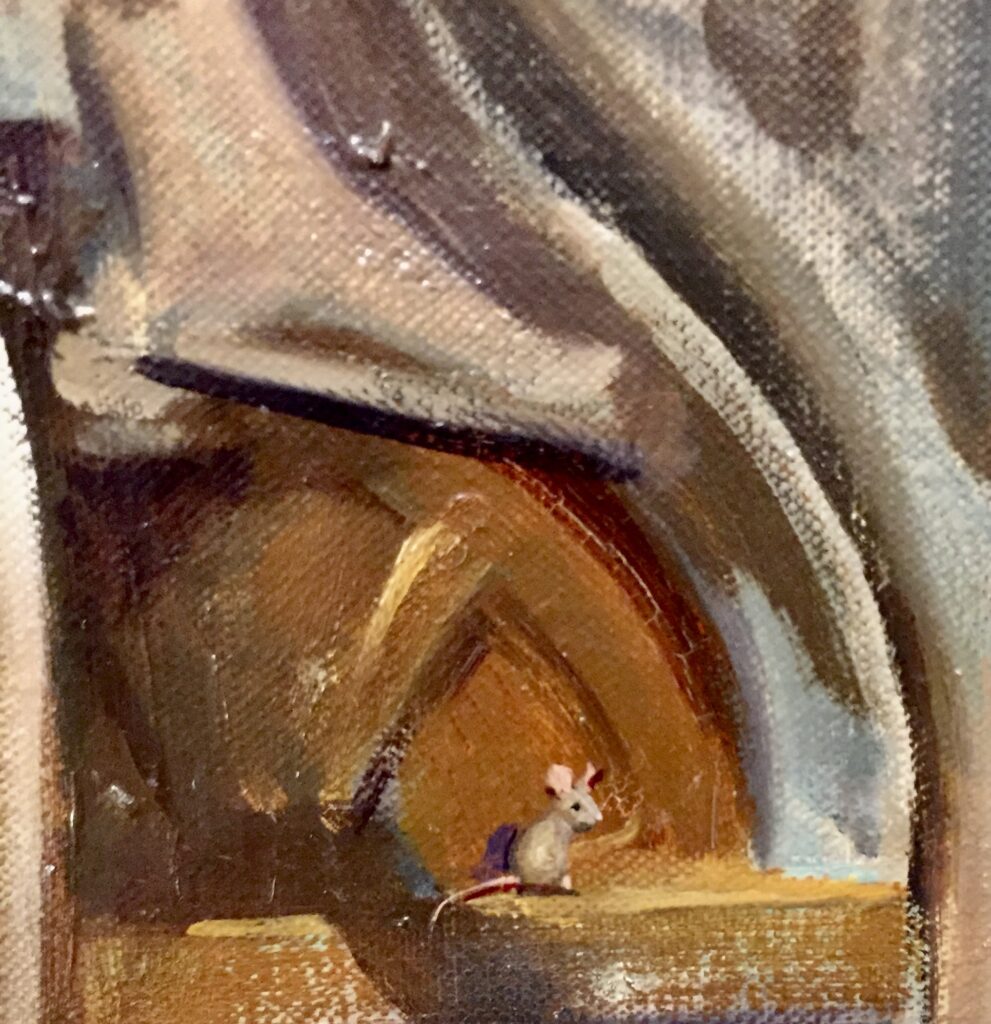

Now for the mice.

These are two of the most impressively detailed paintings on display …

And this one …

Both are by Terence Cuneo (1907-1996).

His most celebrated commission was the official picture of the Coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. One day, as he was painting the huge canvas, his cat brought a dead fieldmouse into his studio. As a distraction from the task in hand, Cuneo painted a portrait of it. Subsequently, a mouse became his ‘signature’ and can be found in every one of his paintings.

There are actually two mice in the first picture above and one in the second.

They are so tiny you won’t be able to find them using this blog and will have to visit the Gallery. They are very difficult to identify, especially the second one, so to help you I took the following pictures …

Good luck!

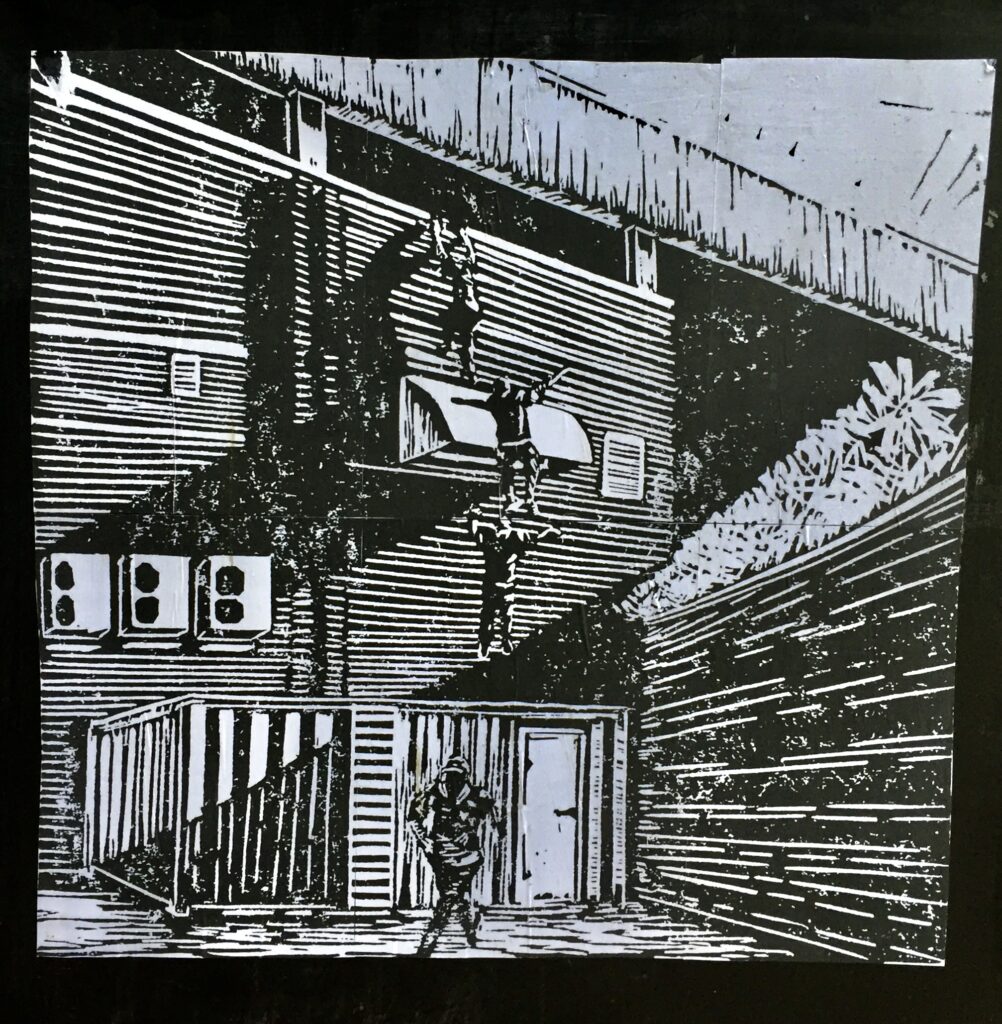

At the far end of the gallery, in a space specially designed for it, you will find at the action-packed painting by John Singleton Copley: Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar 1782 …

A Spanish attack on Gibraltar was foiled when the Spanish battering ships, also known as floating batteries, were attacked by the British using shot heated up to red hot temperatures (sailors nicknamed them ‘hot potatoes’). Fire spread among the Spanish vessels and, as the battle turned in Britain’s favour, an officer called Roger Curtis set out with gunboats on a brave rescue mission which saved almost 350 people.

Look at the painstaking detail in the faces of the officers and Governor General Augustus Eliot, who is portrayed riding to the edge of the battlements to direct the rescue …

The officers were dispersed after the Gibraltar action and poor Copley had to travel all over Europe to track them down and paint them – a task that took him seven years at considerable expense. He recouped some of his cash in 1791 by exhibiting the picture in a tent in Green Park and charging people a shilling to see it.

Incidentally, just outside the entrance is the lovely little Veterans’ Garden created by the Worshipful Company of Gardeners to support the Lord Mayor’s Big Curry Lunch which takes place today (Thursday 30th March). Read all about it here …

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …