Five City churches are currently hosting an exhibition of reproductions of paintings by firefighter artists along with contemporary photographs from the London Fire Brigade archive.

The works are displayed on pop-up screens. For example, this one is at

And this one is in St Mary Aldermary …

You will find details of participating churches at the end of the blog along with opening times.

Here I am going to publish examples of some of the work on display, starting with my favourite, Driving by Moonlight, by Mary Pitcairn …

It depicts an AFS volunteer, Gillian “Bobbie” Tanner, at the wheel of a truck. She was awarded the George Medal for bravery and the citation read: ‘On the night of 20 September 1940, Auxiliary G.K.Tanner volunteered to drive a 30 cwt lorry loaded with 150 gallons of petrol. Six serious fires were in progress and for three hours Miss Tanner drove through intense bombing to the point at which the petrol was needed, showing coolness and courage throughout‘.

During the Second World War, women joined the fire service for the first time as volunteers in the AFS working in a variety of roles ranging from control operators to dispatch riders and delivery drivers.

AFS women despatch riders around 1940 …

A 1941 oil painting by Reginald Mills of Mrs Kathleen Sayer an AFS Station Officer …

The Women’s Division of the AFS had its own leadership structure.

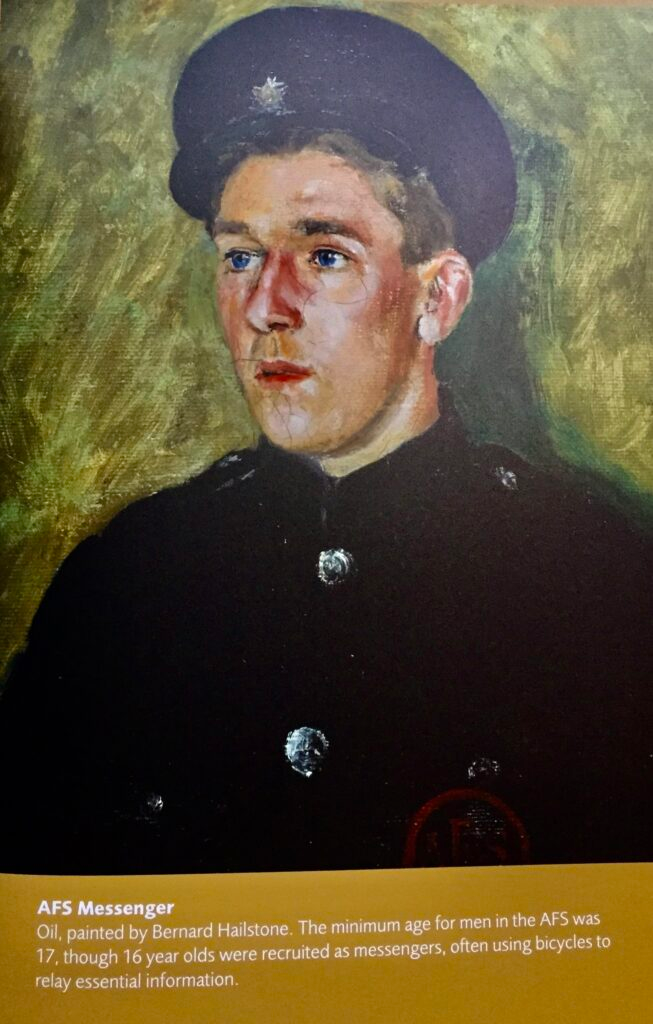

This portrait is by Bernard Hailstone …

After the war Hailstone had a very successful career as a portrait painter. A gregarious, outgoing man, he went on to paint the last officially commissioned portrait of Sir Winston Churchill in 1955 and later members of the Royal family.

Here he is at work as a fireman circa 1940 attaching a hose to a fire hydrant …

Resting at a Fire by Reginald Mills, around 1941 …

These AFS firefighters are surrounded by rolled up hose, resting in the back of an appliance vehicle which pulls a trailer pump, while their colleagues in the background continue to fight a fire. You can see a church spire in the background.

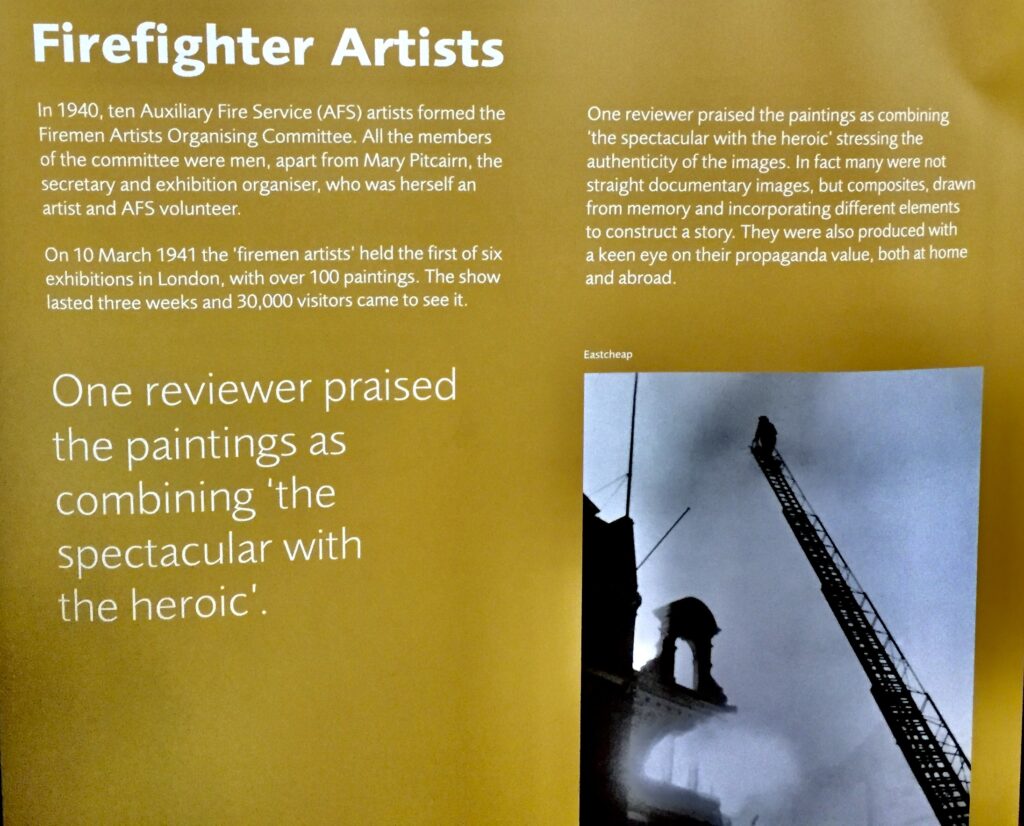

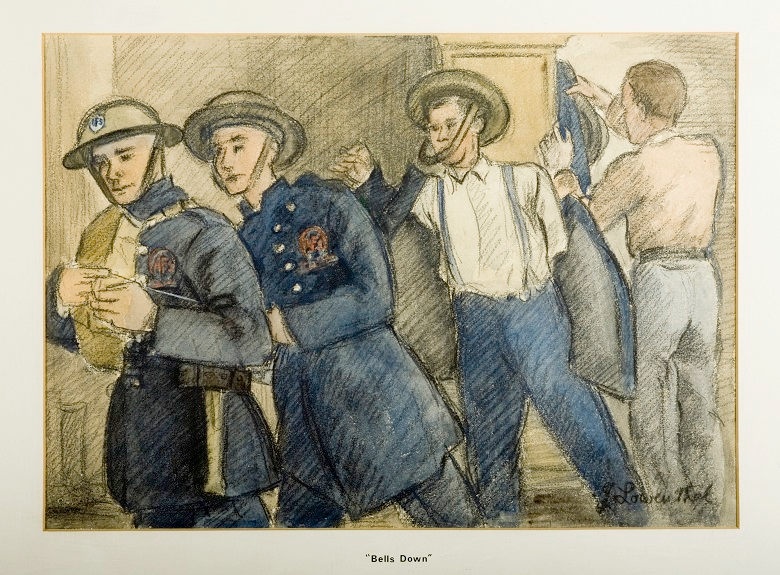

Bells Down by Julia Lowenthal …

Julia Lowenthal’s drawings and paintings gave remarkable insights into life inside the fire stations during the Blitz. Unlike most of her fellow firefighter artists she worked primarily in pencil and watercolour. Lowenthal was based in Kilburn and most of her surviving work is of colleagues in the station, and often at rest. Her watercolour sketch Bells Down refers to firefighters being called to action by bells in their fire station.

At the top of a turntable ladder in Eastcheap directing water into a blazing building, terrifying …

Also terrifying, Run! by Reginald Mills ..

There are examples of extraordinary works by Paul Dessau. In one set, four scenes show different stages of the battle to conquer the flames, much in the style (if not the subject matter) of a Hogarth series. Look closely and you’ll see a monstrous form in each panel. In the first stage, termed Overture by the music-loving Dessau, the bombs begin to fall and a smokey menace looms large over the City …

In Crescendo, the flames take hold as a fiery giant smashes down buildings …

Rallentando, as the name suggest, shows the beast tempered, its infernal form withered but still intimidating …

In the final scene, Diminuendo, the foe lies vanquished amid the smoking rubble, the firemen victorious. Yet the creature has untold siblings who will return night after night to challenge the city’s protectors anew …

Cannon Street – also by Dessau …

Aftermath of a bombing raid near Cheapside with St Paul’s in the background …

Rescuing Horses by Reginald Mills …

Red Sunday, 29 December 1940 by W.S.Haines. Haines was a member of the London River Service and unlike other firefighter artists he was not working in the tight confines of the City of London. This meant he had the opportunity for more panoramic pictorial compositions. Here you can see St Pauls Cathedral and the spires of City churches, through the iconic silhouette of Tower Bridge …

The London Blitz lasted from 7 September 1940 until 11 May 1941 and between 7 September and 2 November heavy bombing continued every night except one. More than 20,000 Londoners were killed including 327 men and women from the fire service with over 3,000 seriously injured. The Germans’ key weapon in the Blitz was the incendiary bomb, a device designed not to explode on impact, but able to burn at 2,500 degrees. Thousands of these were dropped creating fires that threatened to overwhelm the capital.

The firefighter memorial opposite St Paul’s Cathedral …

Part is dedicated to the women who died whilst serving in wartime. The lady on the left is an incident recorder and the one on the right a despatch rider …

Fire in the City is open now and can be seen in the following churches:

- St Mary-le-Bow: Monday to Friday, 7.30am – 6.00pm. Open weekends on an informal basis.

- St James Garlickhythe: Monday to Wednesday, 10.00am – 4.30pm, Thursday, 11.00am – 3.00pm, Sunday: 9.00am – 1.00pm. Friday & Saturday, Closed.

- St Mary Aldermary: Tuesday to Friday, 7.30am – 4.00pm

- St Magnus the Martyr: Tuesday to Friday, 10.00am – 4.00pm, Sunday, 10.00am – 1.00pm (Mass at 11am)

- St Stephen Walbrook: Monday to Friday, 10.30am – 3.30pm

(Venue details may be subject to change so it is advised to check individual church websites for the latest information). The exhibition will move to a second cluster of churches from Monday 23 October until the end of November (with selected venues hosting displays into December).

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …