It was a nice sunny day when I stood in front of this modest little drinking fountain outside St Sepulchre’s Church on Snow Hill near Holborn Viaduct and recalled a picture of the scene on 20th April 1859 when it was unveiled as the first public drinking fountain in London.

A stern reminder to ‘Replace the Cup’ common on many fountains

To me the fountain represents the coming together of some of the great influences on people’s lives in the 19th Century – the philanthropic initiatives of the Quakers, the gradual recognition that access to clean water was essential if London was to continue to flourish, and the temperance and teetotalism movements striving to combat drunkenness.

In the early 19th century water had become a valuable commodity and by 1860 the supply of drinking water to London was controlled by no fewer than eight private companies. It was generally acknowledged that its quality was unsatisfactory to say the least, as outbreaks of cholera earlier in the century had demonstrated. This, combined with a shortage of availability, contributed to a heavy consumption of beer and spirits, particularly among poorer citizens and the ‘labouring classes’ whose workplace was the London streets. Making available free, safe water was to enable a common cause to be established between those seeking to improve hygiene and reduce disease and the anti-alcohol campaigners.

If you look at the picture of the fountain, you might just be able to make out the inscription on the arch above the scallop shell which reads ‘The Gift of Sam Gurney MP 1859’. Gurney was a Quaker, and although Quakers numbered less than 14,000 people in Britain in 1861 their influence in business and philanthropy was disproportionately great – think, for example, of Cadbury, Fry, Barclay and Rowntree. They believed that good works were a sign of man’s sanctification and their economic and religious philosophies ran parallel to one another.

Gurney was present in spring 1859 for the inauguration of The Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association. At the meeting the unveiling in two weeks time of his new fountain was announced along with the intention that it would be the first of many. The Earl of Albermarle got rather carried away and stated his hopes that the fountains would …

Check those habits of intemperance which caused nine-tenths of the pauperism, three-fourths of the crime, one half of the disease, one-third of the insanity, one-third of the suicide, three-fourths of the general depravity and (amazingly) one-third of the shipwrecks that annually occurred.

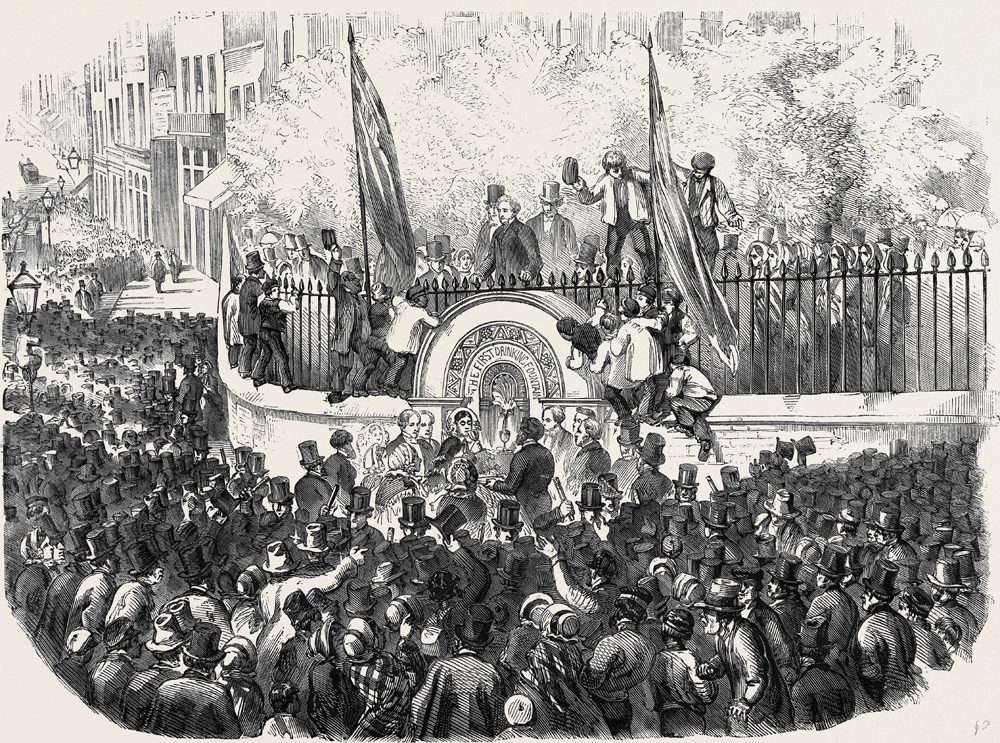

The opening of the fountain was an incredibly well attended event …

Copyright Illustrated London News.

‘The Lady’ newspaper’s view was that the fountains would help by ‘providing an alternative to the public house and the low company found in those establishments’. To demonstrate the water’s purity the inaugural first sip at the opening was taken by a Mrs Wilson – the Archbishop of Canterbury’s daughter, no less – who declared the taste excellent. Just for the removal of doubt, however, a final announcement was made that the fountain was for the special use of the working classes and was committed to their care. Incidentally, Mrs Wilson used a specially engraved silver cup which she was presented with after the ceremony.

Over the next six years 85 fountains were built, most using granite in order to keep the water supply cool. In summer 1865 the Association conducted a twenty-four-hour survey, which produced some very satisfying results. For example, 2,647 drinkers were recorded at the St Sepulchre’s site; at London Bridge more than 3000 people visited and at Bishopsgate an extraordinary 6,666. By 1867 it was estimated that up to 400,000 drinkers a day were using the amenities and by 1875 there were 276 fountains across the capital.

Charles Gilpin was another Quaker whose fountain can still be seen at St Botolph Without Bishopsgate

‘The Gift of C. Gilpin Esq. M.P. 1860’

Getting the fountains built was no easy matter with protracted negotiations often needed with, for example, local vestries, and of course the water companies themselves, who had to be paid for the water used unless they could be persuaded to become donors. Also, water was a precious commodity, and some objected on moral grounds to the wastefulness of the water flowing continuously when the idea of using taps was rejected, given the wear and tear involved. Before the end of its first decade the term ‘free’ in the Association’s title had been recognised as a misnomer and it was dropped. About the same time it elongated its name to the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association to embrace public water provision for animals. Previously troughs had been sited outside public houses with free use only for patrons or on payment of a fee, as one poetic sign declared:

All that water their horses here

Must pay a penny or have some beer

At least one of the horse troughs has survived in the City – although many more can be found around London, usually adapted to accommodate flowers.

Trough and fountain for use by the public, and animals large and small, on London Wall

Remarkably, the cup is also still attached to this nice fountain in Love Lane at the junction with Aldermanbury, the gift of Robert H. Rogers, a Ward Deputy.

Robert H. Rogers’s gift dated November 1890

Love Lane fountain cup and chain

If you thirst for more knowledge about London’s water-related history get hold of a copy of the excellent book ‘Parched City’ by Emma M. Jones on which much of this post is based, including the title.