City churches and their churchyards have so much to offer, and after all these years I am still discovering new quirky items and treasures to write about in my blog. Two church interiors and two churchyards will feature today. I know many of my readers are immensely knowledgeable in this area but I hope there will be something new here even for them.

Once again I suggest you pass through the blue doors at 4 Foster Lane …

Entrance to St Vedast Fountain Courtyard and Cloister

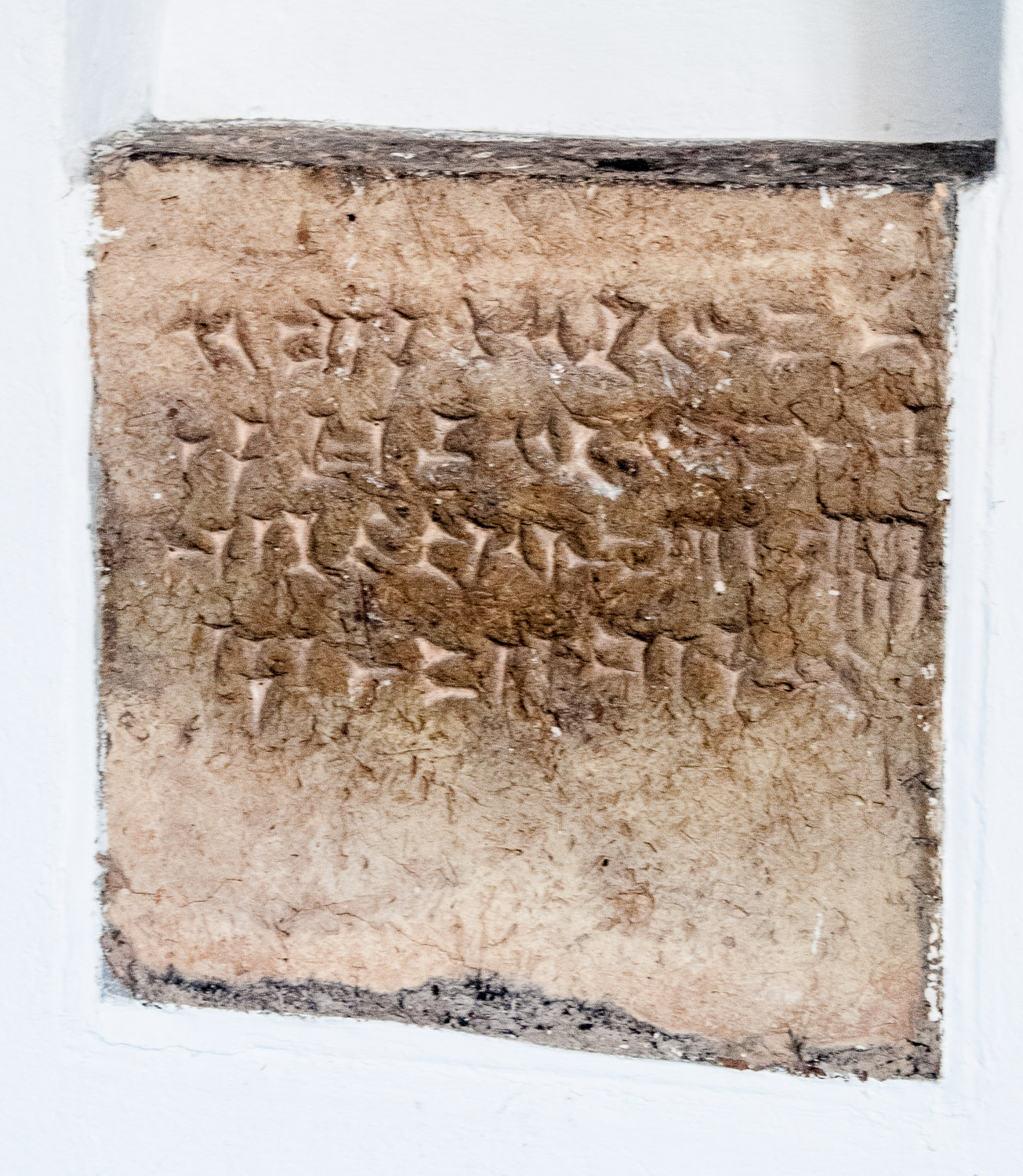

Near the piece of Roman pavement I discussed in an earlier blog (The Romans in London and Two Roman Ladies) you will see displayed in a niche a tablet with cuneiform writing.

It comes from a 9 BC Iraqi Ziggurat and was given to the Rector, Canon Mortlock, by Agatha Christie’s husband, the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan. He discovered the brick during a 1950-65 dig and apparently it includes the name of Shalmaneser who ruled from 858 to 834 BC.

Just down the road from Pudding Lane, the source of the Great Fire, St Magnus the Martyr on Lower Thames Street was the second church to be destroyed in 1666. It was rebuilt by Wren circa 1671-84 and, despite being damaged in the Blitz, it has a great atmosphere – especially on a Sunday when lots of incense has been deployed.

It is worthy of an entire blog all to itself, but for today I will be writing about just a few of its fascinating features. First of all there is the portico you walk through to enter the church …

The view towards Lower Thames Street

Between 1176 and 1831 the churchyard formed part of the roadway approach to Old London Bridge. I found it easy to imagine the tens of thousands who passed through here, since it was the only bridge across the Thames until Westminster Bridge was opened in 1750. Despite the heavy passing traffic, and the lavatorial white tiles on the nearby buildings, this is an atmospheric place and I paused there thinking of all those forgotten souls who had walked these flagstones before me.

The clock (top left in the picture) was presented in 1709 by Sir Charles Duncombe when he was Lord Mayor. One legend tells us that, as a poor saddler’s apprentice living south of the river, he was often severely reprimanded by his master for being late because he had no way of telling the time. Now immensely wealthy, he gifted the clock for the benefit of other folk who could not afford a timepiece.

Right inside the door is a lovely surprise – a 17th century fire engine …

It once belonged to St Michael Crooked Lane. It has only recently been displayed in the narthex having been in store with the Museum of London since 1945.

And if the fire engine wasn’t enough to prompt a visit, what about this extraordinary model of the Old London Bridge …

My picture really does not do it justice – it is four metres long and portrays the bridge at the start of the 15th century

It was created in 1987 by David T Aggett, a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Plumbers. The detail is superb, from the individual tiles on the lead roofing, to the countless individuals crushing into the roadway or hanging out of windows. Over nine hundred tiny people are crammed onto the bridge, amongst them a miniature King Henry V, who can be seen processing towards the City of London from the Southwark side of the bridge. No wonder it is estimated that the bridge usually took more than an hour to cross.

This window on the south side remembers the St Thomas a Becket chapel which was situated near the centre of the bridge …

See if you can find the Chapel on the model

The chapel paid a levy to St Magnus from the fees received from travellers crossing the river.

I paid another visit to St Sepulchre-without-Newgate at the junction of Holborn Viaduct and Snow Hill. Housed there, in a glass case, is a macabre relic – the Newgate Execution Bell …

Photo by Lonpicman

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the clerk of St Sepulchre’s was responsible for ringing a handbell outside the condemned person’s cell in Newgate Prison, just across the road where the Old Bailey court is now. A tunnel linked the church to the prison and at midnight, on the night before their execution, the bell would be rung twelve times and the following ‘wholesome advice’ delivered …

“All you that in the condemned hole do lie,

Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die.

Watch all, and pray, the hour is drawing near,

That you before Almighty God will appear.

Examine well yourselves, in time repent,

That you not to eternal flames be sent,

And when St Sepulcher’s bell tomorrow tolls,

The Lord above have mercy on your souls.”

The tradition of ringing the bell apparently dates from 1605 and has its origins in a bequest of £50 made by one Robert Dow(e), a prominent member of the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors. Dow had apparently wanted a clergyman to be the one to ring the bell but £50 was insufficient to cover the extra cost.

On the day of execution, the condemned were ‘carted away’ and ‘went west’ from Newgate to the Tyburn gallows (near today’s Marble Arch), the death cart pausing outside St Sepulchre’s for the prisoners to be presented with a nosegay. The distance between Newgate and Tyburn was approximately three miles, but due to streets often being crowded with onlookers, the journey could last up to three hours. A usual stop of the cart was at the Bowl Inn in St Giles where the condemned were allowed to drink ‘strong liquors or wine’.

The tremendous disruption caused by the thousands who came to watch eventually became too much for the authorities and the last execution at Tyburn took place on Friday the 7th of November 1783 when John Austin was hanged for highway robbery. Public executions continued outside Newgate Gaol until 1868 and still attracted vast crowds, the last person dispatched being the Fenian Michael Barrett on the 28th May that year.

Looking down from St Sepulchre’s is this sundial. Dating from 1681 it will have witnessed many of the sad events associated with the old prison. You can read more about it, and other dials, in my blog We are but shadows – City Sundials.

The dial is made of stone painted blue and white with noon marked by an engraved ‘X’ and dots marking the half hours.