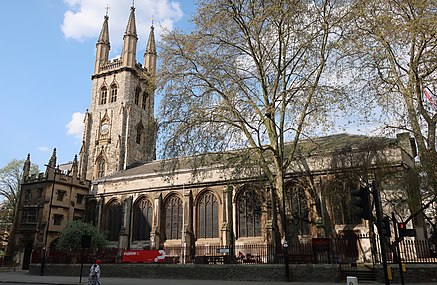

I have been a bit unlucky in the past when, walking towards Holborn Viaduct, I have found this church closed. Last weekend, however, my luck was in and I ventured inside. I am delighted I did.

The porch, tower and outer walls date from the mid-15th century …

The interior is a bit of a mixture of late 17th century to mid-Victorian …

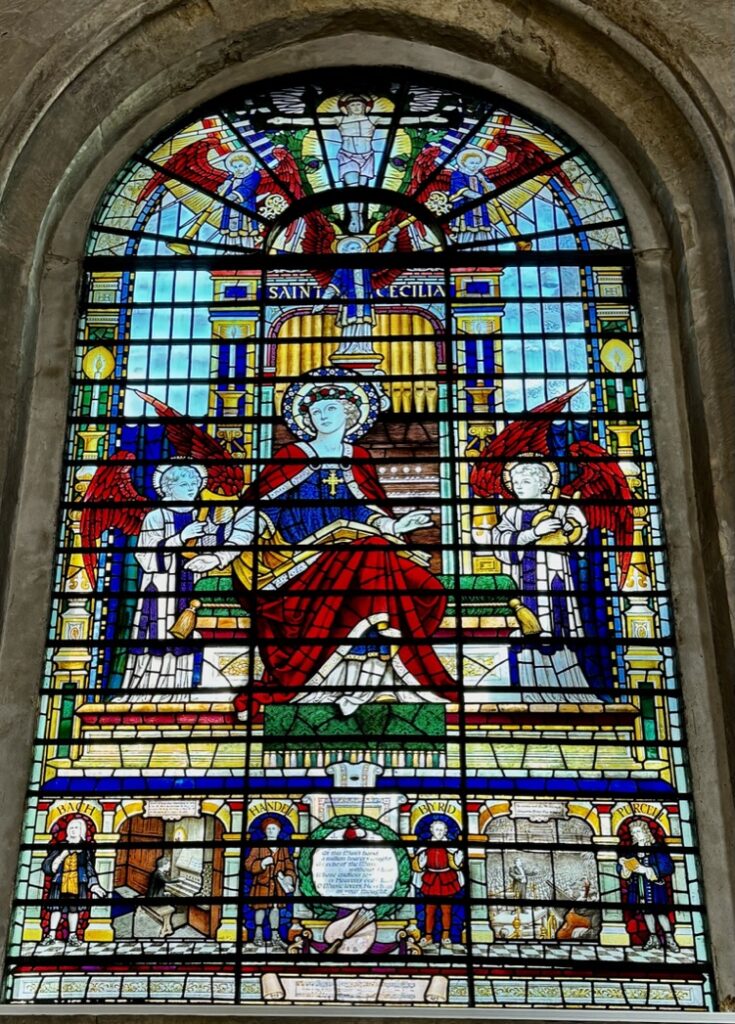

The first thing that struck me was the quality of the stained glass.

A window removed for safe keeping during the War …

St Bernard with some of his followers …

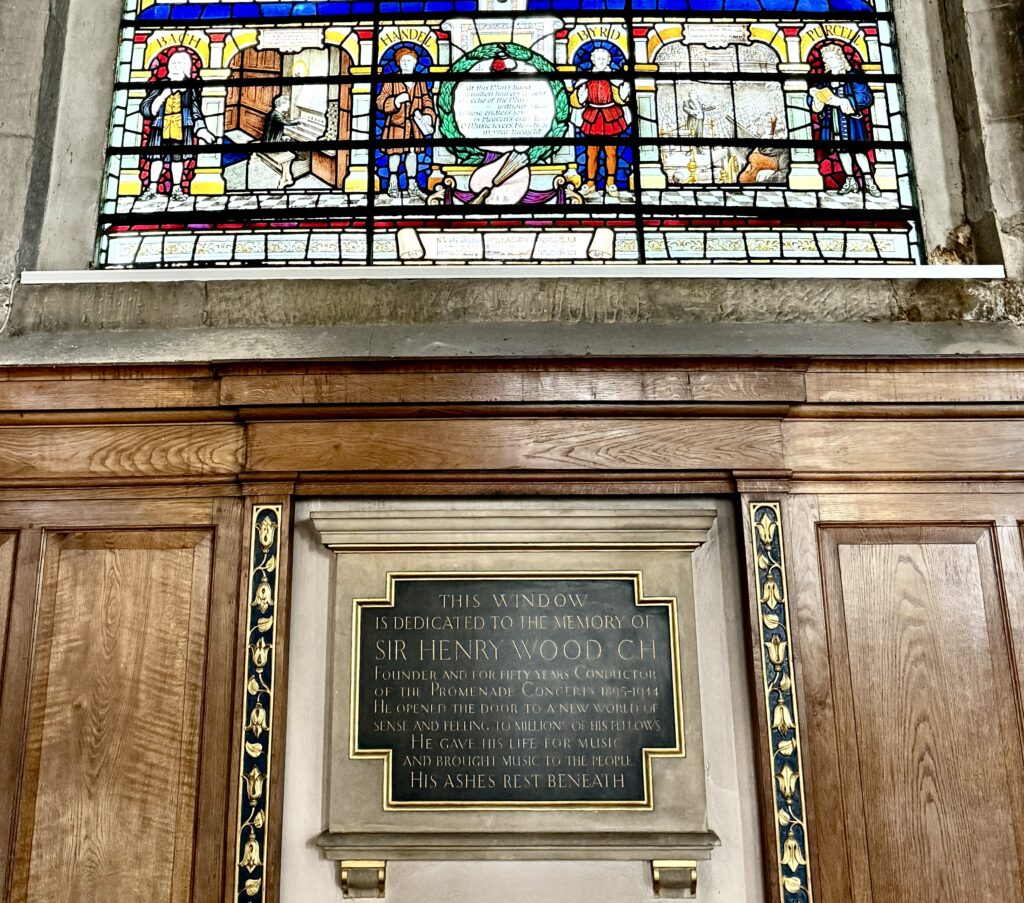

I stopped to admire the glass in the Musicians’ Chapel.

This is the burial place of Sir Henry Wood, founder and conductor of the Proms for nearly 50 years, in memory of whom there is a window and a memorial plaque …

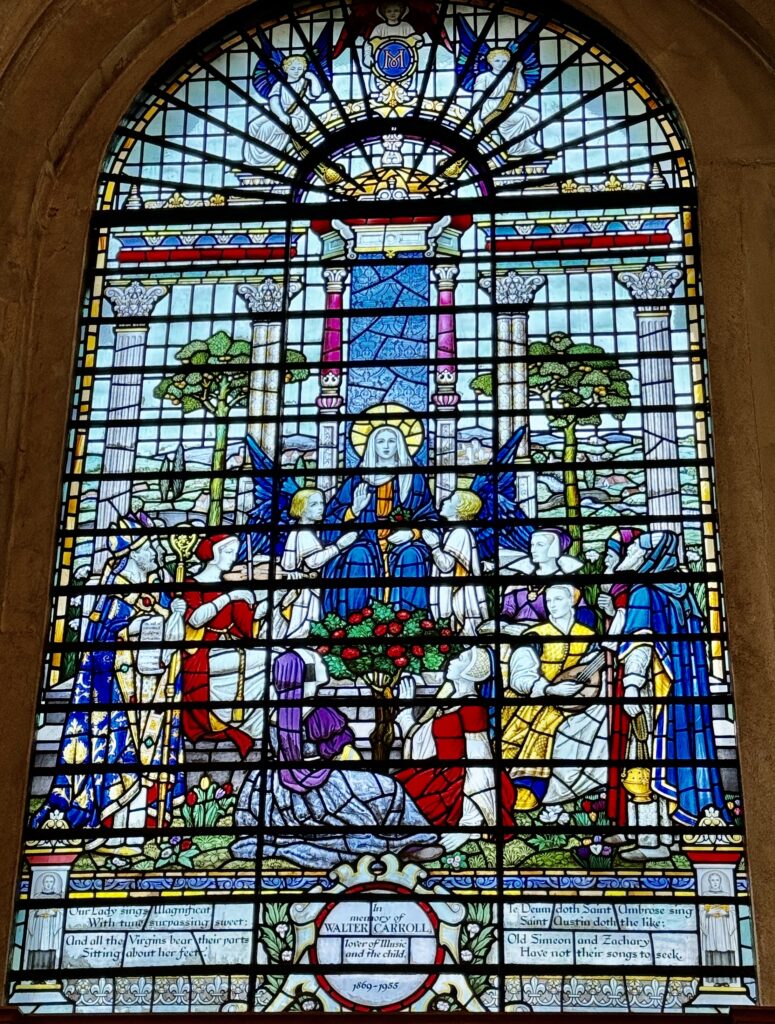

There is a window to Walter Carroll who lived from 1869 till 1955 in Manchester. He was a composer and a music teacher, especially known for his music for children, which he wrote for his two daughters Ida and Elsa …

Dame Nellie Melba, an Australian operatic lyric coloratura soprano, also has a commemorative window. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early 20th century and was the first Australian to achieve international recognition as a classical musician …

For centuries, the church had a close association with the notorious Newgate Prison which stood across the road where the Old Bailey is now.

Carts carrying the condemned on their way to Tyburn would pause briefly at the church where prisoners would be presented with a nosegay. However, they would already have had an encounter with someone from the church the night before. In 1605, a wealthy merchant called Robert Dow made a bequest of £50 for a bellman from the church to stand outside the cells of the condemned at midnight, ring the bell, and chant as follows:

All you that in the condemned hole do lie, Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die; Watch all and pray, the hour is drawing near, That you before the Almighty must appear; Examine well yourselves, in time repent, That you may not to eternal flames be sent: And when St. Sepulchre’s bell tomorrow tolls, The Lord above have mercy on your souls.

And you can still see the bell today, displayed in a glass case in the church …

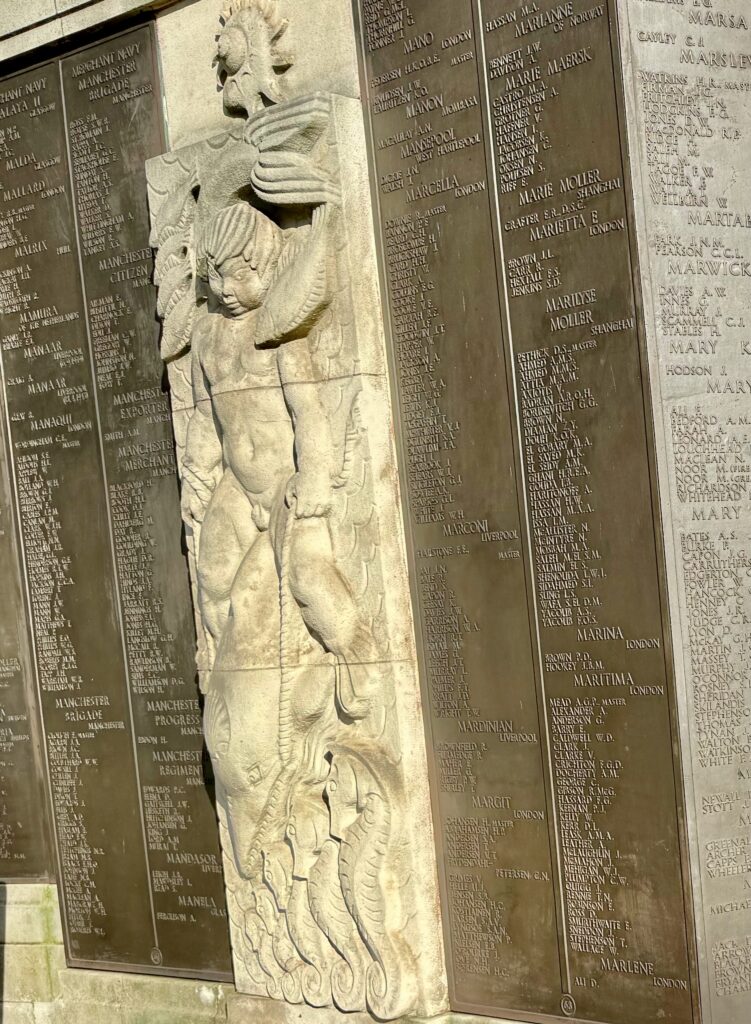

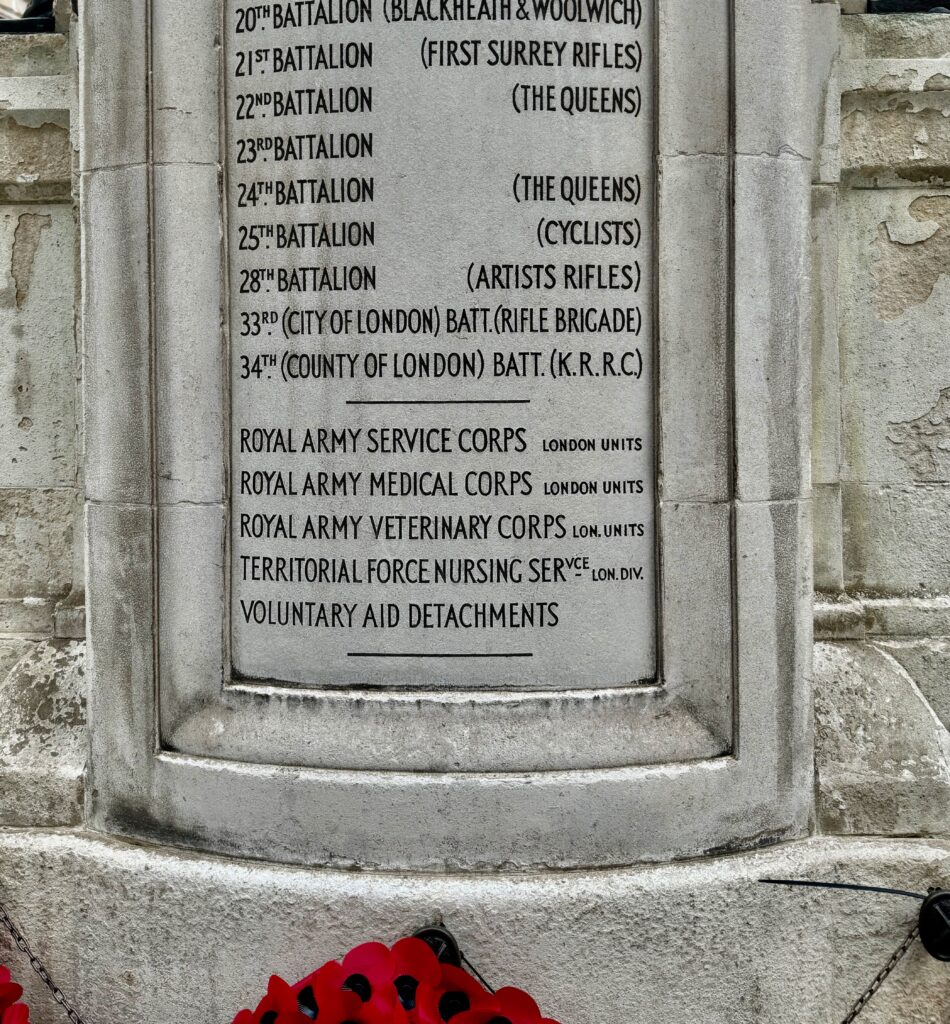

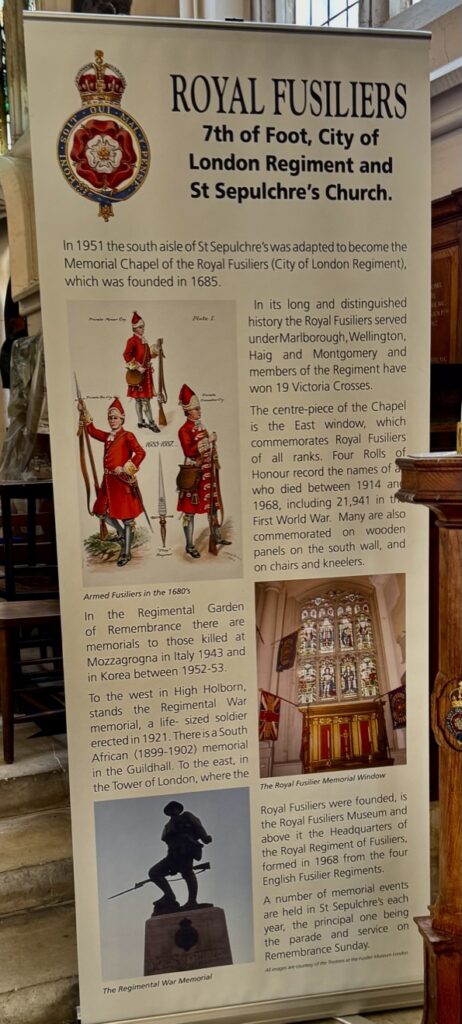

The south chapel is dedicated to the City of London Regiment of the Royal Fusiliers …

Regimental colours dating back to the 19th century are on display …

The terrible carnage of the First World War is recalled by some of the battle honours recorded here …

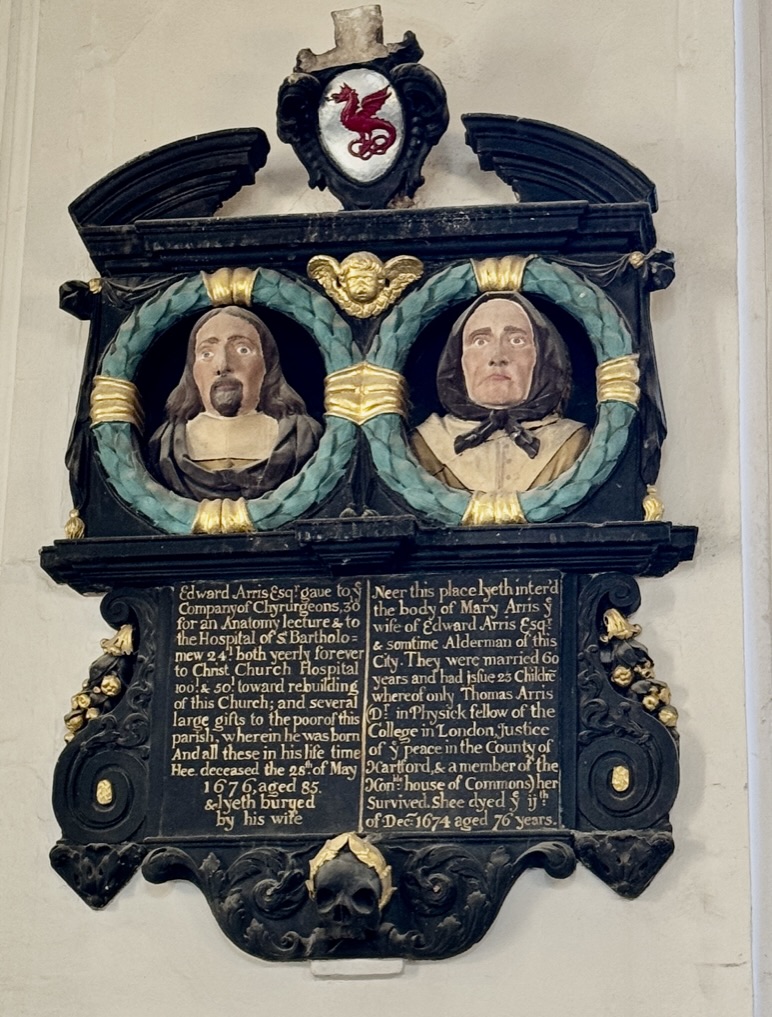

I am so delighted that I looked up and noticed this memorial …

I quote here from the Worshipful Company of Barbers’ website:

Edward Arris was a distinguished surgeon and Master of the Barbers’ Company. He died in 1651, two years after his wife Mary. Their marriage had lasted 60 years and produced 23 children, only one of whom (Thomas) survived their mother.

The inscription reads: ‘Edward Arris Esq gave to ye company of Chyrurgeons 30l for an anatomy lecture & to the Hospital of St Bartholomew 24l both yearly forever to Christ Church Hospital 100l & 50l towards rebuilding of this church; and several large gifts to the poor of this parish, wherein he was born. And all these in his life time. Hee deceased the 28 May 1676 aged 85 and lyeth buryed by his wife.‘

The money Arris provided to the Company in 1645 – a benefaction he attempted to keep secret – founded six lectures and a dissection in the Inigo Jones Anatomy Theatre annually. His name (along with that of another Master of the Company) and these lectures live on today as the Arris and Gale Lecture at the Royal College of Surgeons.

Besides providing grooming services, barber-surgeons regularly performed dental extractions, bloodletting, minor surgeries and sometimes amputations. The association between barbers and surgeons goes back to the early Middle Ages, hence the blood and bandages sign outside barber shops today.

This beautiful font cover was donated by a parishoner in 1670 …

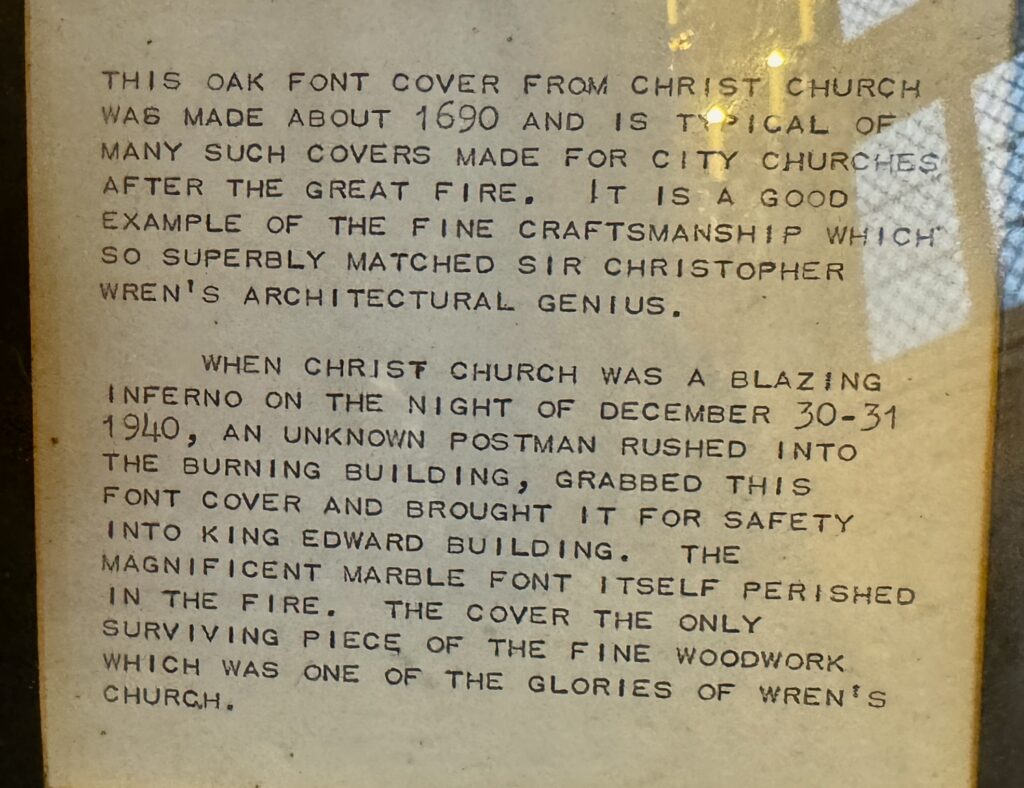

There is another font cover nearby with a thrilling back story …

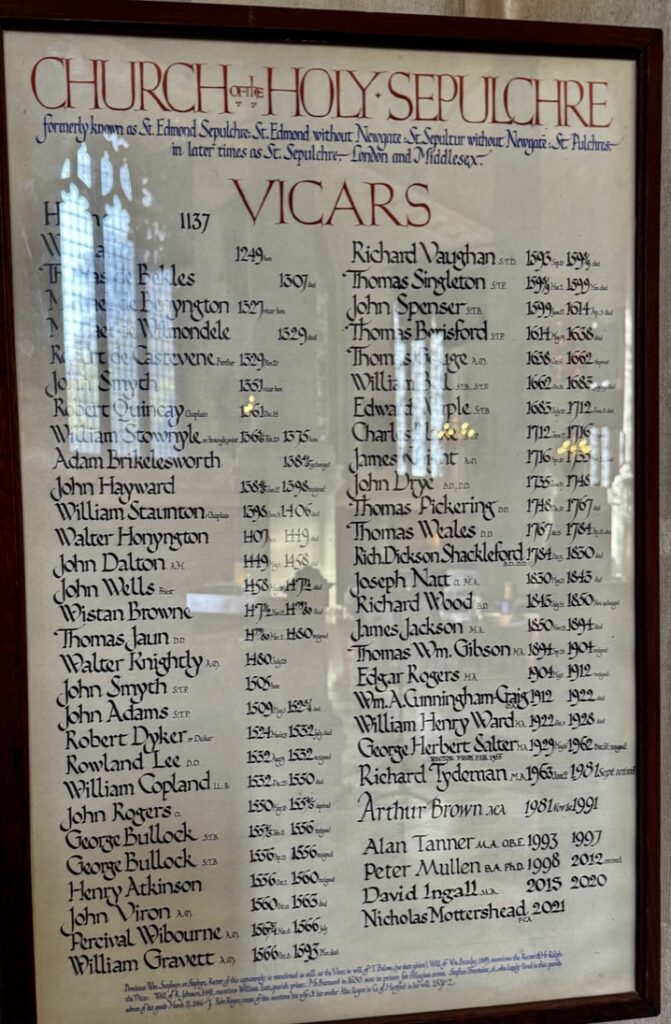

Vicars going back to the 12th century …

When you leave the church there is one other thing to look out for – the first ever public drinking fountain installed in London …

You can read all about it in my earlier blog entitled Philanthropic Fountains.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …