The Sculpture in the City project is always worth a visit, which is what I did last week. I have also added some other pieces that caught my eye.

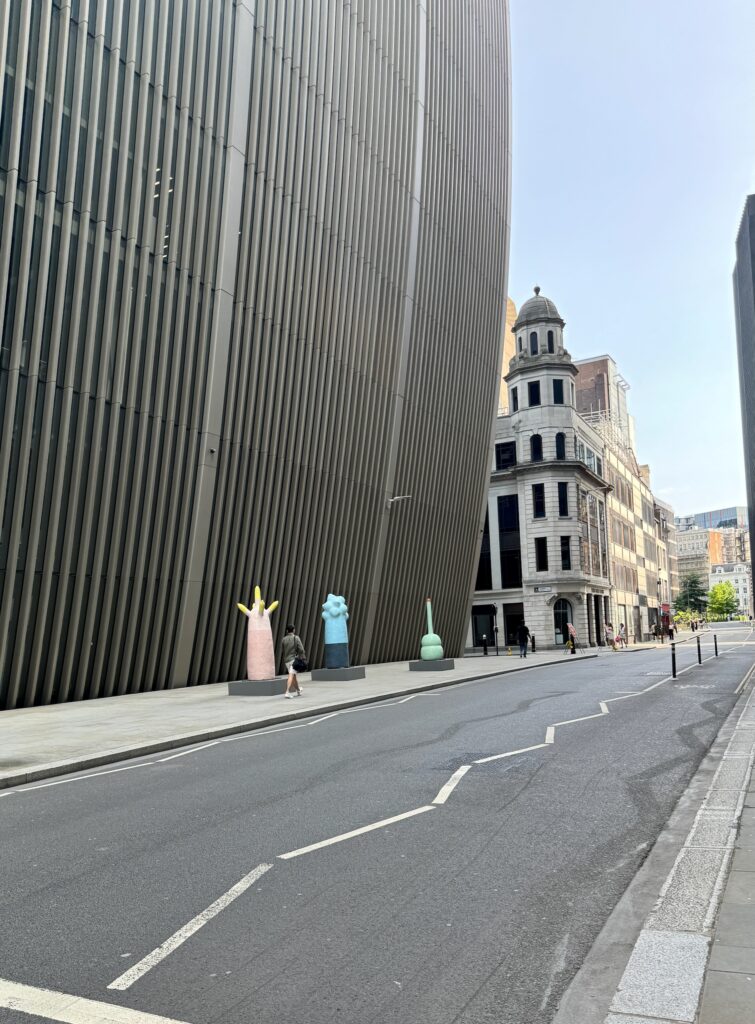

First up is this one entitled Temple by Richard Mackness. It’s on the corner of Bishopsgate and Wormwood Street, EC2M 3XD…

‘In this object, questions of belief and value weave with consumer culture and the human need to find meaning and to belong’. You can read a fuller description here.

This one has been around since last year but I’m including it again because I like its location. It’s called Muamba Grove, 0 Hue 1 and 2 by Vanessa da Silva and can be found at St Botolph-without- Bishopsgate Churchyard, EC2M 3TL …

‘The artist’s process offers an indication of the inseparable link between the body and the sculpture – the artist’s own body becomes entwined within the making of the forms. Da Silva’s use of colour and carefully considered scale contributes to the sense of dynamic and fluid movement’. You can read more here.

If you visit the churchyard look out for St. Botolph’s Hall, once used as an infants’ school, but now a multipurpose church hall available for hire. At its front entrance is a pair of Coade Stone figures of a schoolboy and girl in early nineteenth century costumes …

In the foreground is the large tomb of Sir William Rawlins, Sherriff of London in 1801 and a benefactor of the church …

This is Book of Boredom by Ida Ekblad. It’s at Undershaft, EC2N 4AJ (in front of Crosby Square) …

‘Conveying a rich sense of abundance and corporality, this painted bronze sculpture presents a vibrant composition filled with fragmented, angular patterns and shapes, merging elements of figuration and abstraction’. You can read more here.

This is Untitled by Arturo Herrara at the base of the Leadenhall Building EC3V 4AB …

‘Untitled reflects the dynamic movement of people using the space and the mechanic stairs. Both designs energise the area under the stairs with an all over composition that mimics the traffic and activity of this large urban space in the City’.

I caught my first glimpse of these creatures, called Secret Sentinels, as I turned from St Mary Axe into Bevis Marks (EC3A 8BE). They made me smile, which is a good start! …

They were created by Clare Burnett …

‘Secret Sentinels is a family of sculptures made from found objects and materials and covered in glass tiles. The sculptures are inspired by how we balance privacy against convenience in relation to state and private surveillance. The protrusions from each piece gently reference the surrounding, ubiquitous cameras in the City security systems, doorbells, phones and computers’. You can read more here.

Here are the other things that caught my eye during my walk that are not part of the Sculpture in the City project.

Infinite Accumulation by Yayoi Kusama is an extraordinary sculpture on the pavement outside the Liverpool Street Elizabeth Line station entrance …

Another work now on permanent display is outside Moorgate Station and was created by the British artist Conrad Shawcross RA. It’s called Manifold (Major Third) 5:4 and was installed late last year as the penultimate artwork for the Crossrail project. According to a sign close to the art, ‘this vast bronze sculpture is an expression of a chord falling into silence’ …

You can read more here.

The open space at Citypoint is currently a temporary home to Squiggle …

Moving away from sculpture, I like the coloured glass deployed around 22 Bishopsgate …

Thomas Bayes (circa 1701-1761) has been in the news lately for all the wrong reasons due to the sudden sinking of the yacht named after him and the tragic loss of seven lives. You can read the BBC news report here.

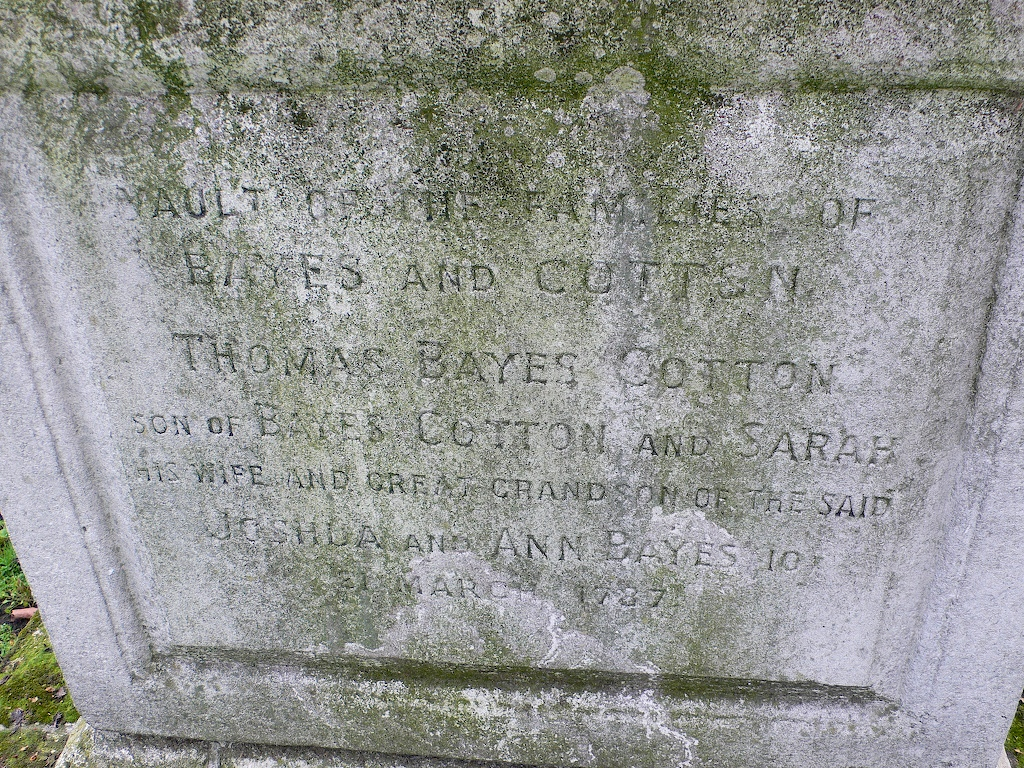

I thought you might be interested to know that Bayes is buried in a family grave in Bunhill Fields Burial Ground. It can be easily seen from the paths but the inscriptions are rather indistinct (despite restoration in 1969 funded by statisticians worldwide) …

In the vault are laid members of the Bayes, Cotton and West families.

The inscription on the east side of the tomb (Wikimedia Commons)…

On the top of the tomb is inscribed: Rev. Thomas Bayes, Son of the said Joshua and Ann Bayes (59).

The west side, Miss Decima Cotton who died on 12 April 1795 …

Born in Hertfordshire, Bayes studied at Edinburgh University and began his preaching career in that city; he later assisted at his father’s meeting-house on Leather Lane in Holborn before being appointed Presbyterian minister to the Little Mount Sion meeting-house at Tunbridge Wells in 1731, which post he occupied until his retirement 20 years later. During his lifetime Bayes published nothing under his own name, although he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1742, perhaps on the basis of an influential defence of Newtonian mathematics published anonymously in 1734. His fame rests chiefly upon his mathematical ‘Essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances’, published posthumously in 1764; this adumbrates the highly influential ‘Bayesian’ approach to probability theory, as well as containing the famous ‘Bayes’ Theorem’, still widely used in statistics and information technology.

I was fascinated to find out that, armed with powerful computers to handle the data, American security experts use Bayesian inference to prioritise potential threats to the nation. You can read more here.

I found this image of the grave after restoration in 1969 …

I think it’s time to get the scrubbing brush out again!

On a more cheerful note, about 200 yards away is this building …

Concerned about Sir John Cass’s connection with the slave trade, the Business School that bore his name decided to rebrand themselves and, in an online poll, ‘Bayes Business School’ was the winning suggestion. I think it’s nice that his final resting place is so nearby!

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …