More animals this week with, of course, a nod to Her Majesty’s special weekend. More of this chap and his friends later …

Researching this blog has led me to some fascinating facts. I didn’t, for example, know that a cockerel is a young male bird which, after it’s a year old, is called a rooster. Generously, I provide important information like this to my blog subscribers free of charge.

The rooster had profound religious significance. In the Bible, Jesus foretold that Peter, one of his most devoted disciples, would betray him. “…Verily I say unto thee, that this night, before cock crow, thou shalt deny me thrice.” (Matthew 26:34). And so the rooster became an emblem of Peter’s betrayal. Sometime between 590 and 604 A.D., Pope Gregory I declared that the rooster, emblem of St. Peter, was the most suitable symbol for Christianity. In the 9th century, Pope Nicholas made the rooster official and declared that that all churches must display the rooster on their steeples or domes. I’ve found three in the City.

All Hallows-by-the-Tower …

St Andrew Undershaft …

And St Dunstan-in-the East …

The weathervane above the Rookery Hotel in Smithfield references the nearby meat market …

The building is at the junction of Cowcross Street and Peter’s Lane. Wander down the Lane and you’ll see that the brick walls of the tower have been embellished with bulls’ and cows’ heads modelled and cast in glass reinforced resin by Mark Merer and Lucy Glendenning. The bovine theme was used as a decorative motif because for centuries Cowcross street was part of a route used by drovers to bring cows to be slaughtered at Smithfield …

Another bull at the Smithfield Tavern on Charterhouse Street (EC1M 6HW) …

A herd moves along the north side of the street opposite the meat market …

Two rams are following up the rear. There a quite few of them around the City.

At the end of New Street off Bishopsgate (EC2M 4TP) you will find this one over the gateway leading to Cock Hill …

It’s by an unknown sculptor, dates from the 186os and used to stand over the entrance to Cooper’s wool warehouse.

The Worshipful Company of Clothworkers have a ram in their coat of arms, Here one presides over the entrance to Dunster Court, Mincing Lane (EC3R 7AH) …

I have always been curious about these ram’s heads on the corner of St Swithen’s Lane and Cannon Street …

I consulted a great source of City knowledge, The City’s Lanes and Alleys by Desmond Fitzpatrick. He writes that …

For well into the second half of the last century, the building was a branch of a bank dealing with services to the wool trade, a business connection pleasantly expressed … by the rams’ heads crowned with green-painted leaves, as if Bacchus and Pan had met!

There are sheep in the City too.

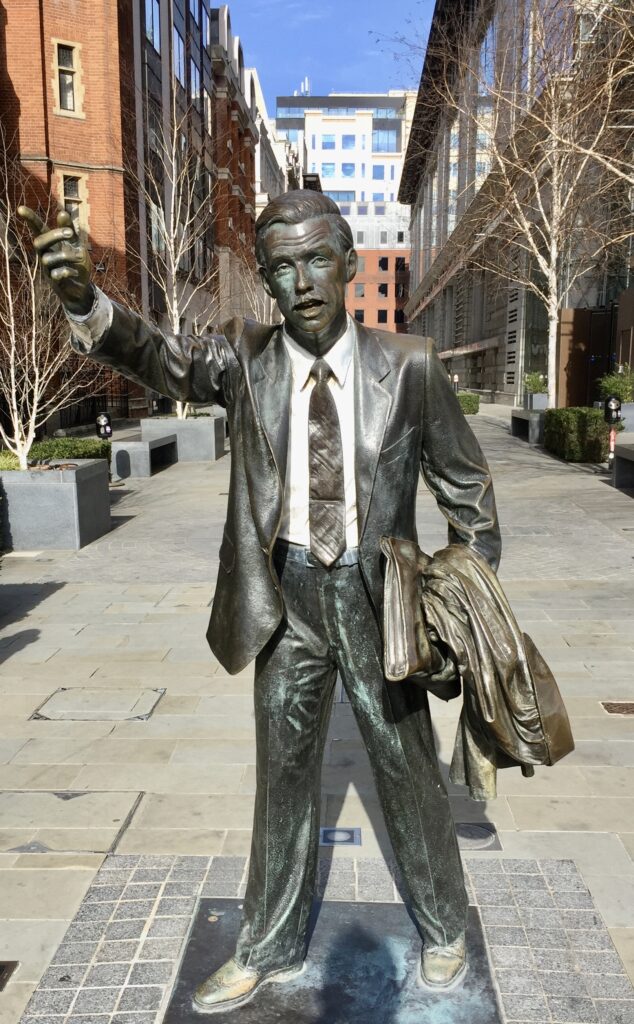

In Paternoster Square is a 1975 bronze sculpture by Elisabeth Frink which I particularly like – a ‘naked’ shepherd with a crook in his left hand walks behind a small flock of five sheep …

Dame Elisabeth was, anecdotally, very fond of putting large testicles on her sculptures of both men and animals. In fact, her Catalogue Raisonné informs us that she ‘drew testicles on man and beast better than anyone’ and saw them with ‘a fresh, matter-of-fact delight’. It was reported in 1975, however, that the nude figure had been emasculated ‘to avoid any embarrassment in an ecclesiastical setting’. The sculpture is called Paternoster.

Outside Spitalfields Market, is the wonderfully entitled I Goat. In the background is Hawksmoor’s Christ Church …

It was hand sculpted by Kenny Hunter and won the Spitalfields Sculpture Prize in 2010.

The sculptor commented …

Goats are associated with non-conformity and being independently-minded. That is also true of London, its people and never more so than in Spitalfields.

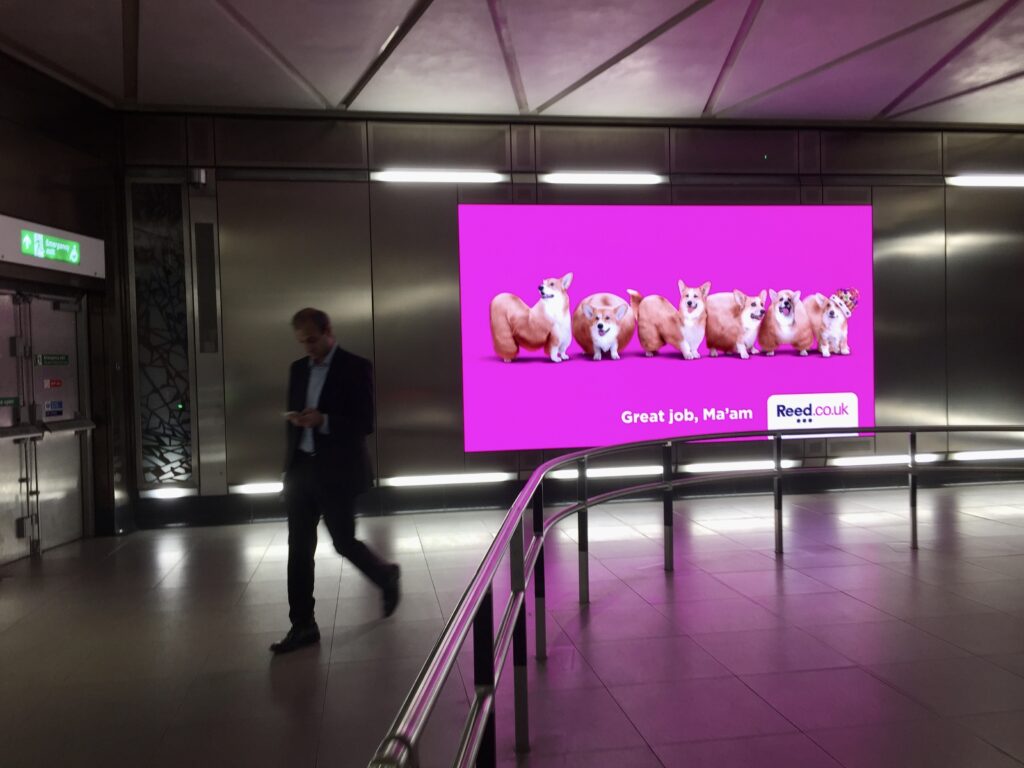

And now to those Corgis.

I just had to visit the magnificent Elizabeth Line shortly after it opened. Looking down the escalators at Farringdon I noticed a flash of pink on the left …

Fortunately I didn’t have to run backwards to get a close up shot since you’ll find these little creatures looking out at you on numerous walkways and platforms …

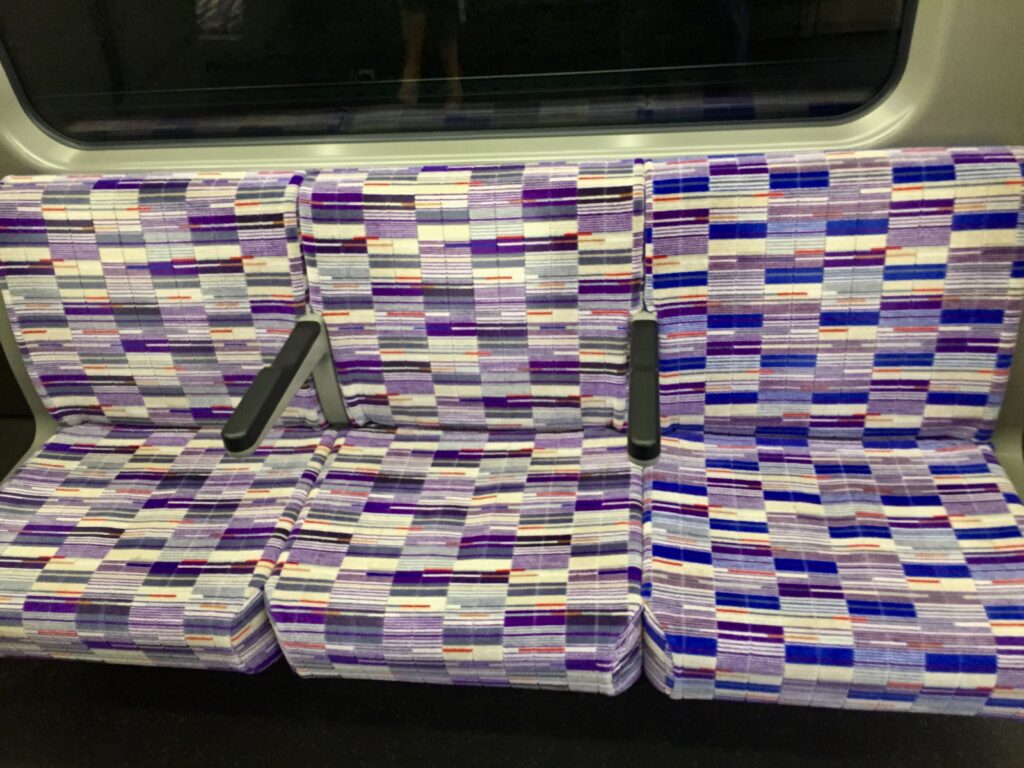

Inside the carriages you can admire the specially designed moquette …

‘Moquette’ is a woven pile fabric. With an almost velvet-like texture, it’s comfortable but still extremely durable, making it ideal for seats on public transport. Transport for London’s moquette designs tend to consist of a repeat geometric pattern, making it easy to match fabrics when upholstering seats, as well as helping to reduce wastage and keep costs down. You can read more about the background to the design here.

If you really like it you can buy a matching scarf and socks! Or maybe a nice bench – a snip at £450. If you’re working from home perhaps you could sit on it and pretend you’re commuting.

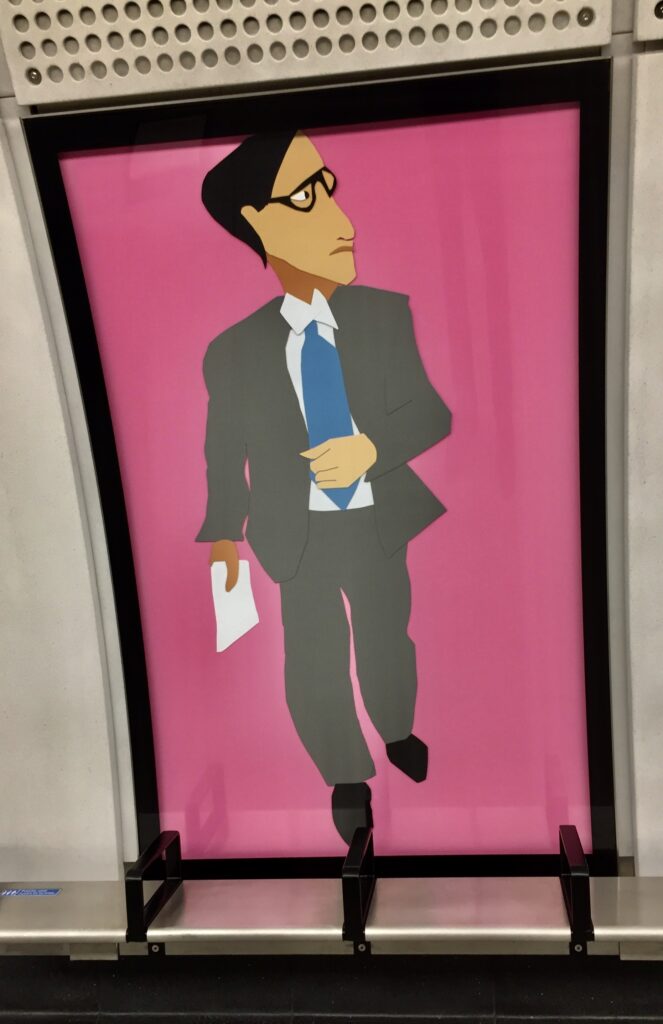

I took the train to Whitechapel and had a quick look at some of the portraits by Chantal Joffe. She has lived in east London for many years and her 2m-tall portraits are made from laser-cut aluminium. They’re inspired by her Sunday wanderings among the cosmopolitan crowds thronging the streets and markets around the station—a neighbourhood that has been home to many of London’s migrant communities for centuries. Here are a few examples of her work …

Definitely worth a visit.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …