In 1500 there were 15 churches in the City of London dedicated to a St Mary. It was by far the most popular dedication with the next most popular being All Hallows (8 churches) and St Michael (7 churches). This, of course, was helped by the fact that there are two St Marys – Mary the Virgin, the mother of Jesus and Mary Magdalene one of Jesus’s followers who was present at the crucifixion. But even if we count only the churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary, it is still the most popular dedication with a total of 13.

I’ve already written in some detail about the six Marys still in existence but for some reason I rather neglected paying serious attention to St Mary Aldermary – an omission I intend to put right in this week’s blog. Incidentally, the name ‘Aldermary’ possibly derives from ‘Older Mary’ meaning the oldest church in the City dedicated to her.

As every guide to the church will tell you – when you enter just look up!

The nave …

The south side aisle …

The north side aisle …

The fabulous plaster fan-vaulted ceiling is more reminiscent of a cathedral and St Mary’s is the only parish church in England known to have one.

It is unclear why Wren chose to rebuild the church (1679-82) in an uncharacteristically Gothic style. Funding came from a personal estate, so it may have been the desire of the executors, or possibly the will of parishoners. Whatever the cause, the fortunate result is arguably the most important late 17th century Gothic church in England.

A quirky feature of the church is the angle of the east wall which followed the line of a pre-1678 passage …

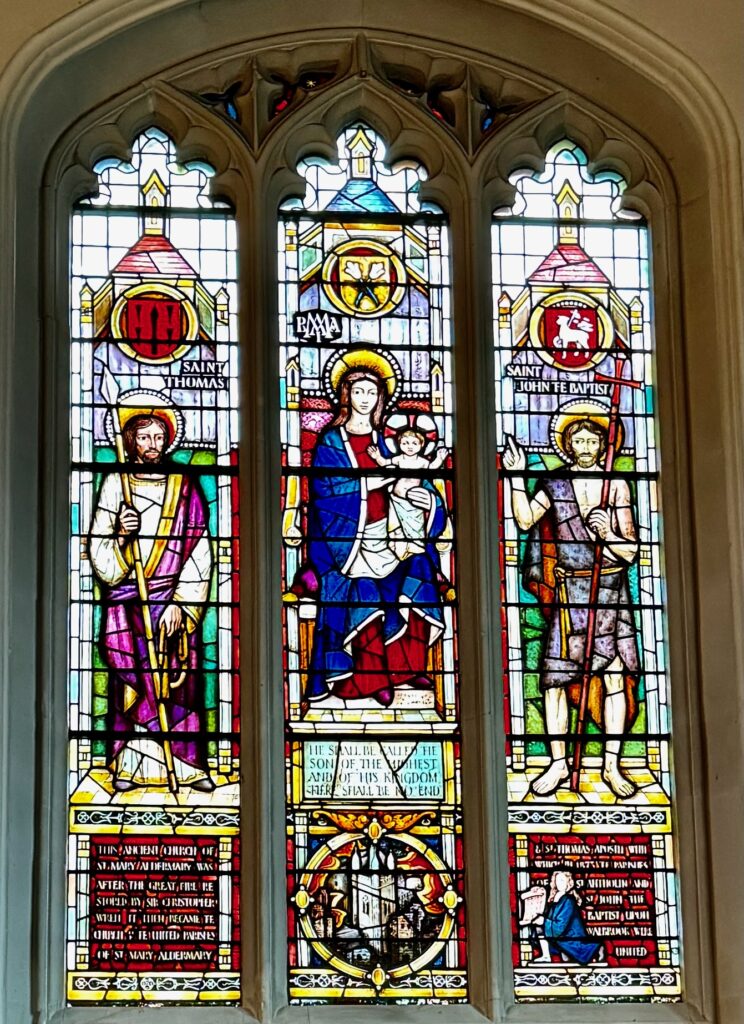

One of the the east windows by Lawrence Lee (1955) is ‘a fusion of sacred and secular with St Thomas, St John the Baptist and Madonna and Child above and panels depicting important episodes from the dramatic history of the church below. The gothic church tower powerfully depicted appears engulfed in the flames of the Great Fire of London of 1666’ …

In close up, Sir Christopher Wren kneels to present his plans for the new church …

The west window by John Crawford commemorates the defence of London against air attack in the 1939-45 War. It depicts the Risen Christ in Glory with the Hand of God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the form of a Dove. Above are the Instruments of the Passion, while below are the emblems of the four Evangelists. The lower lights show St Michael overcoming the Dragon, representing the force of good vanquishing evil, with St Peter (left) and St Paul (right). At the base is a panorama of London and at the top the arms of the various Services involved …

A blocked off window above the north door, dating from 1876, depicts the Transfiguration …

The pulpit is thought to have been carved in 1682 by Grinling Gibbons …

The organ was built by George England in 1791 …

This beautiful, rare wooden sword rest dates from 1682 …

You can read more about the fascinating history of sword rests here.

The font was a gift from a wealthy parishoner called Dutton Seaman in 1627. One commentator describes it as having been ‘designed with jacobean gusto’ …

There is a plaque to James Braidwood, who was married in the church in 1838. He was the first Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment and formed the world’s first municipal fire brigade in Edinburgh. He died tragically whilst fighting the terrible Tooley Street Fire of 1861. You can read all about him and the fire in which he perished in my Tooley Street Fire blog …

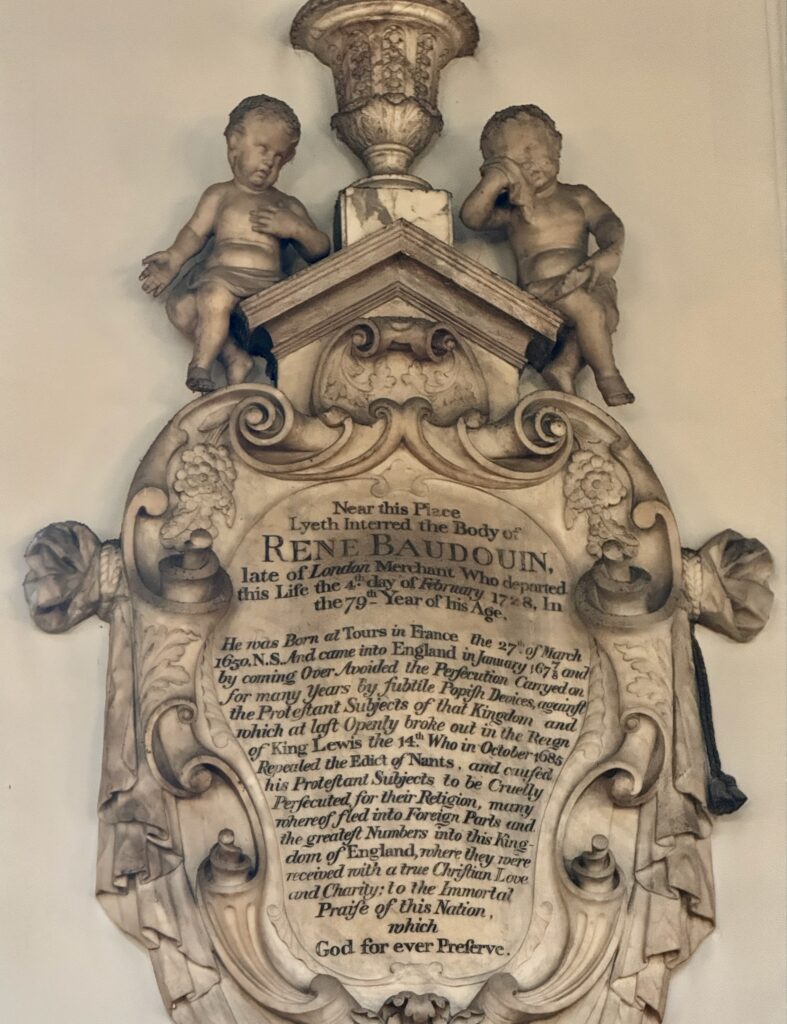

René Baudouin was a Huguenot refugee from Tours in France. He established himself in Lombard Street, London, with a silk merchant Etienne Seignoret. The pair were successful but they were fined for continuing to trade with France during the Anglo-French war (1689-1697) …

There is also a memorial to the brilliant surgeon Percivall Pott who I wrote about in last week’s blog.

St Mary is the regimental church of the Royal Tank Regiment – ‘Once a Tankie always a Tankie’ …

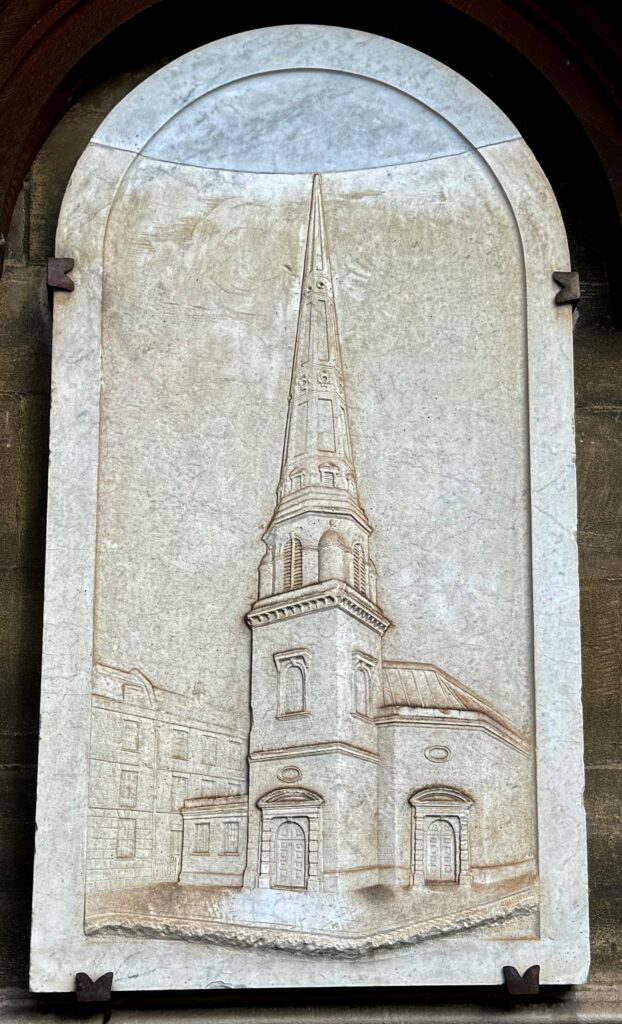

The nearby old City church of St Antholin was demolished in 1875 and the parish merged with St Mary’s. A plaque on the wall outside memorialises this union …

If you entered St Mary’s from the west, the door casing you walked through came from St Antholin …

The best view of the church is from the south side of Queen Victoria Street …

The golden finials at the top of the tower are now, I’m told, made of fibreglass!

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …