An important date for your diary! This Saturday, 5th October, at 11:30 a.m. I will be interviewed by Robert Elms on his BBC Radio London show. We’ll be chatting about my book Courage, Crime and Charity in the City of London and I hope you will be able to join us.

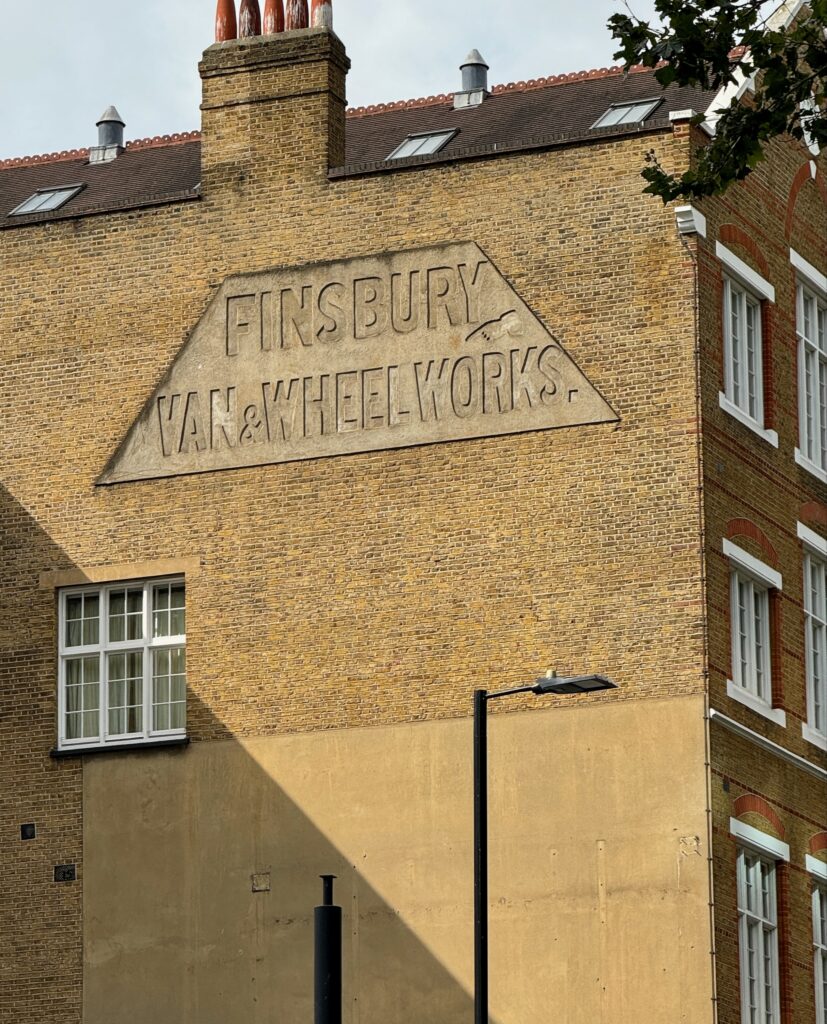

On a sunny day last week I took a walk towards Holborn and picked out a few buildings and memorials that I really liked.

First up is the Wax Chandlers Hall …

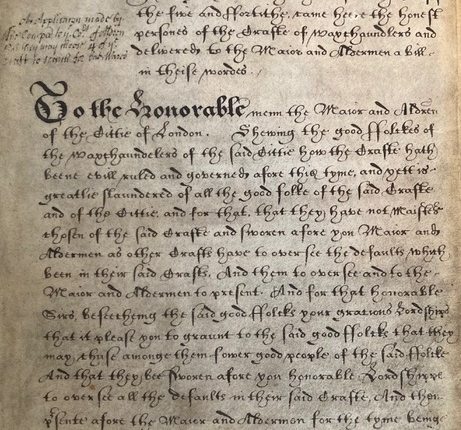

Wax Chandlers’ Hall is on Gresham Street on a site that the Company has owned since 1501. It has a long and fascinating history stretching all the way back to 1371 when they applied to the City’s governing body, the Mayor and Court of Aldermen, to have officials appointed from among their number (masters) to ‘overse all the defaults in theyre saide crafte’, and see that offenders were prosecuted. Their history is really well documented on their website.

Surely the bluest door in the City with the finest unicorns …

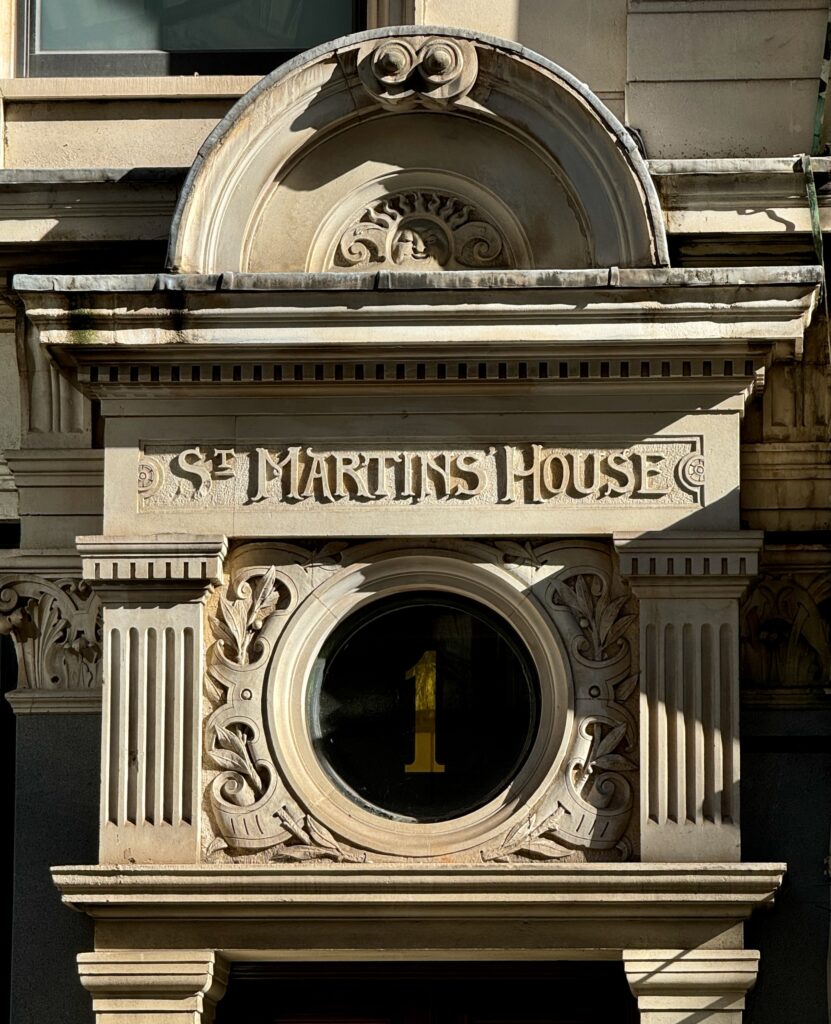

On the next corner is the building with the rogue apostrophe and the happy smiling sun…

Surely that should be St Martin’s House?

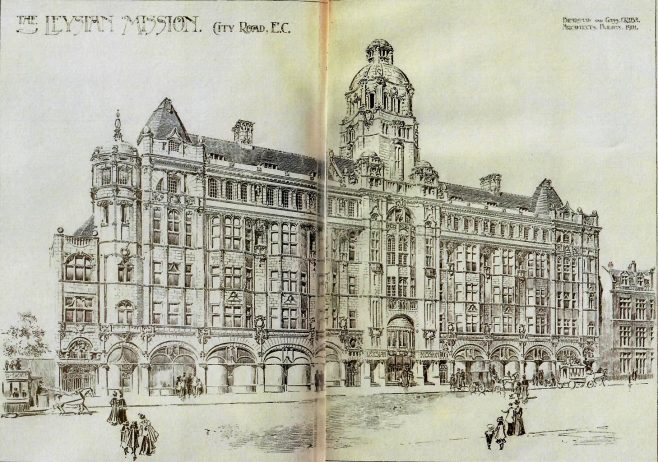

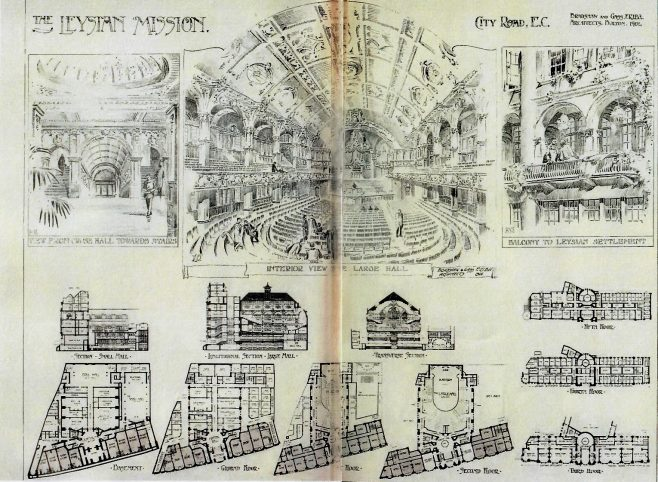

So many fine buildings date from the late 19th and very early 20th century …

The General Post Office in St. Martin’s Le Grand was the main post office for London between 1829 and 1910, the headquarters of the General Post Office of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and England’s first purpose-built post office …

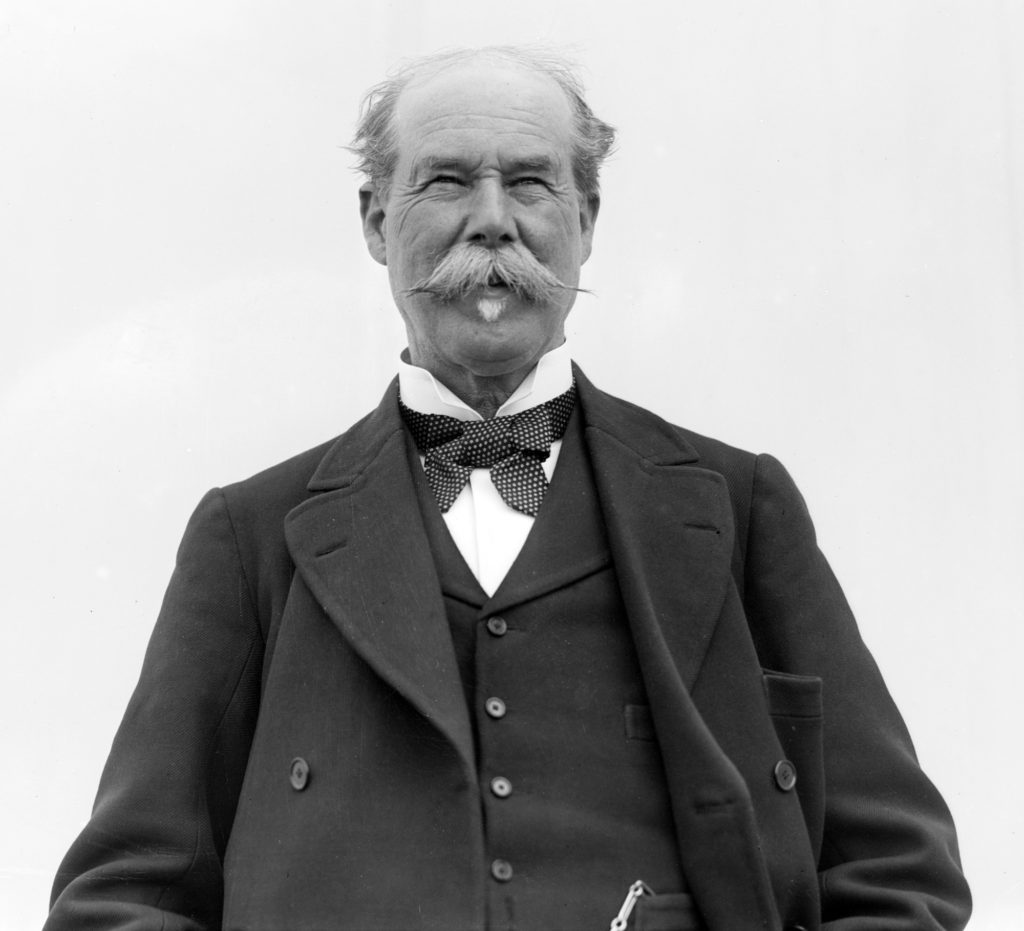

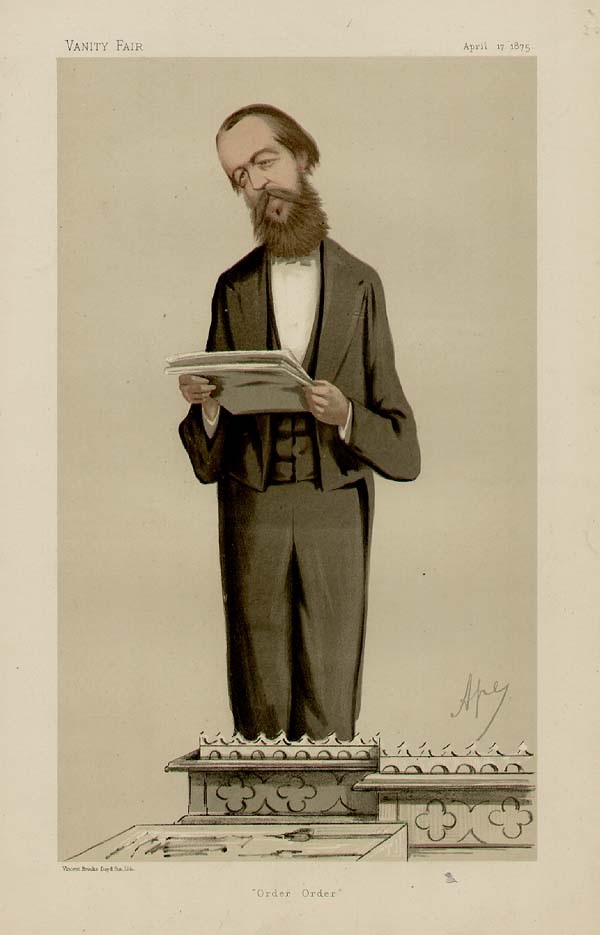

Poor Henry Cecil Raikes, who laid this stone, died in August the following year aged only 52. Here he is in a Vanity Fair caricature when he was Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons …

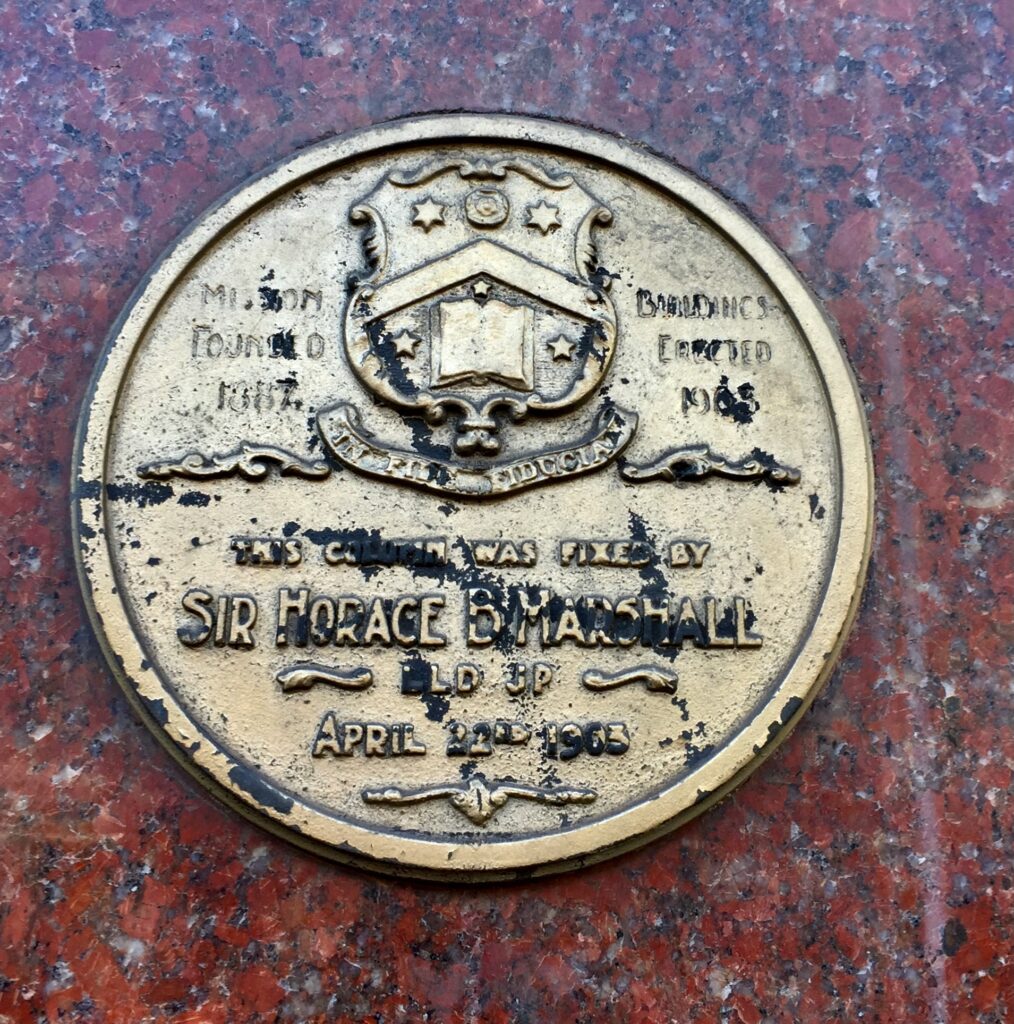

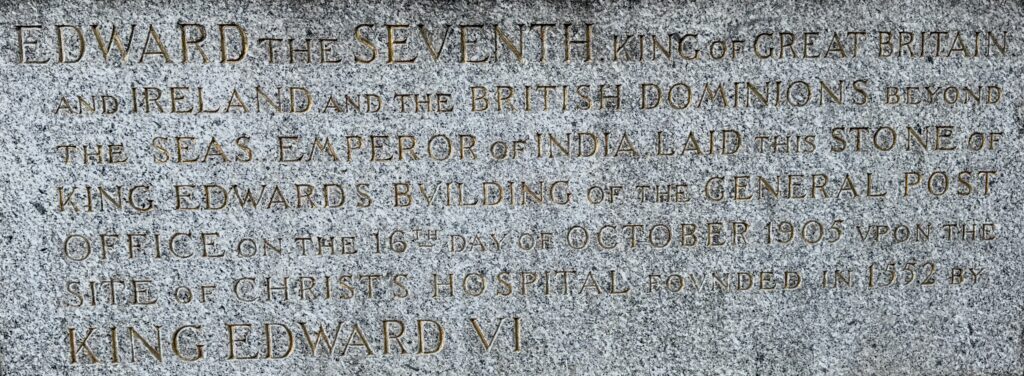

Parallel is King Edward Street where the man himself laid this stone on 16th October 1905 …

The great British Empire is duly acknowledged along with the King’s connection to an earlier Edward and the foundation of Christ’s Hospital.

It’s commemorated again nearby with this sculpture, the ragamuffins on the right being carefully coaxed towards a better life …

To me they look like they are having a fine time just as they are, perhaps letting it all hang out at a concert …

Is it my imagination or does the kid on the left look like the late Anthony Armstrong Jones …

On Newgate Street another building connected to the Post Office …

This imposing building is at 16/17 Old Bailey. The London Picture Archive tells us: The seven-storey building was designed for the Chatham and Dover Railway Company by Arthur Usher of Yetts, Sturdy and Usher of London in 1912. The building is in the Edwardian baroque style with elements of french architectural styles such as the mansard roof … …

Above the entrance is a broken pediment with statues either side depicting travel. The statue of the woman on the left holds a wheel depicting rail travel and the woman on the right leans on an anchor depicting sea travel. At the bottom of brackets on the two piers either side of the entrance are small carved lion heads …

Across the road, outside the church of St Sepulchre Newgate, is this modest little drinking fountain which has an intriguing history …

Read all about it in my blog Philanthropic Fountains.

Look up towards the roof of the church and you’ll see a late 17th Century sundial …

The dial is on the parapet above south wall of the nave and is believed to date from 1681. It is made of stone painted blue and white with noon marked by an engraved ‘X’ and dots marking the half hours. It shows Winter time from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm in 15 minute marks. I thought it was curious that the 4:00 pm mark is represented as IIII rather than IV – I have no idea why

There is demolition going on in the approach to Holborn Viaduct and I couldn’t resist taking this image of what looks like a building that has been sliced away revealing the vestiges of decoration left on each floor …

I find it reminiscent of the ruined houses on bomb sites that used to be a common feature of London right up to the early 1970s.

Holborn Viaduct dragons and a knight in armour …

As Prince Albert doffs his hat towards the City of London, a terracotta masterpiece looms in the background …

Before walking towards it I made a quick detour to St Andrew Holborn to admire the Charity Boy and Girl …

… and the extraordinary Resurrection Stone …

You can read more about it here in the excellent Flickering Lamps blog .

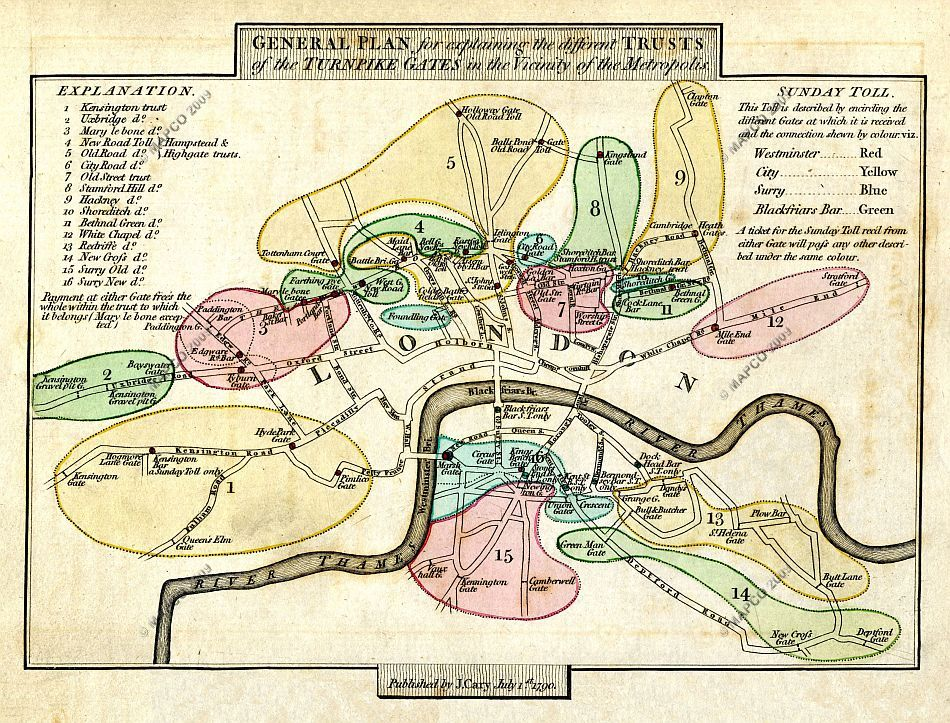

Pausing at the junction with Grays Inn Road, and looking back east, you will see that you are at one of the entrances to the City guarded by a dragon …

In the background is the Royal Fusiliers War Memorial, a work by Albert Toft. Unveiled by the Lord Mayor in 1922, the inscriptions read …

To the glorious memory of the 22,000 Royal Fusiliers who fell in the Great War 1914-1919 (and added later) To the Royal Fusiliers who fell in the World war 1939-1945 and those fusiliers killed in subsequent campaigns.

Toft’s soldier stands confidently as he surveys the terrain, his foot resting on a rock, his rifle bayoneted, his left hand clenched in determination. At the boundary of the City, he looks defiantly towards Westminster. The general consensus on the internet is that the model for the sculpture was a Sergeant Cox, who served throughout the First World War.

Behind him is the magnificent, red terracotta, Gothic-style building by J.W. Waterhouse, which once housed the headquarters of the Prudential Insurance Company.

As is often the case, I am indebted to the London Inheritance blogger for some of the detail about this extraordinary building . The Prudential moved into their new office in 1879, which was quite an achievement given that the company had only been founded 31 years earlier in 1848. The building exudes Victorian commercial power and was a statement building for the company that was at the time the country’s largest insurance company …

The lower part of the building uses polished granite, with red brick and red terracotta across all upper floors. If you stare at the building long enough the use of polished granite gives the impression that there has been a large flood along Holborn, which has left a tide mark on the building after washing out the red colour from the lower floors.

In the centre of the façade is a tower, with a large arch leading through into inner courtyards around which are further wings of the building …

It incorporates a sculpture of Prudence carrying one of the attributes of this Virtue, a hand mirror …

When built, the Prudential building was very advanced for its time. There was hot and cold running water, electric lighting, and to speed the delivery of paperwork across the site, a pnematic tube system was installed, where documents were put into canisters, which were then blown through the tube system to their destination. Ladies were provided with their own restaurant and library, and had a separate entrance, and were also allowed to leave 15 minutes early to “avoid consorting with men”.

The building’s brickwork is very attractive …

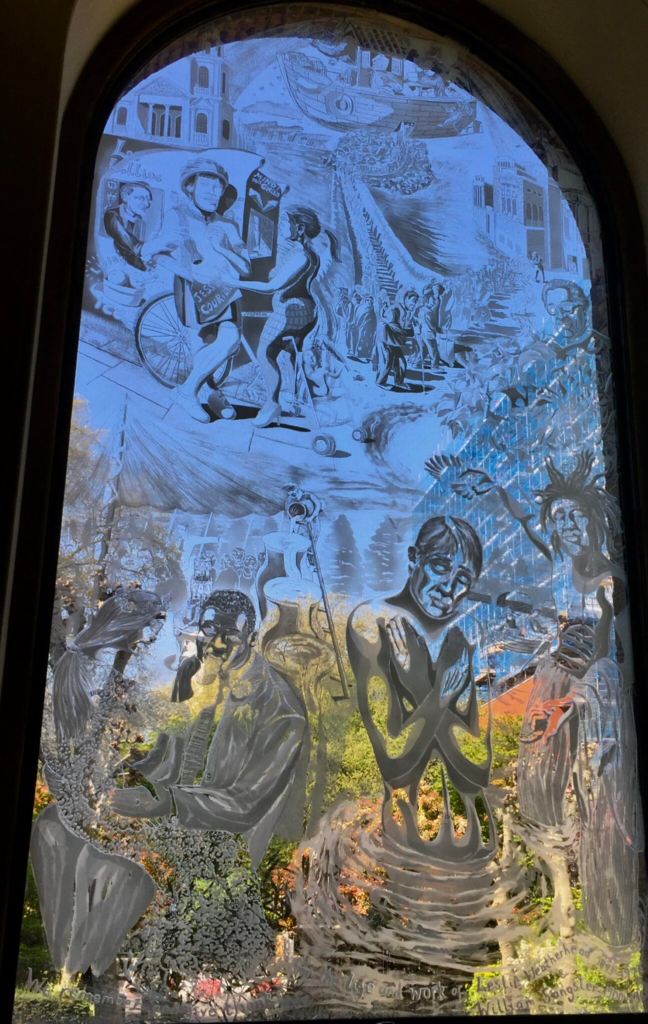

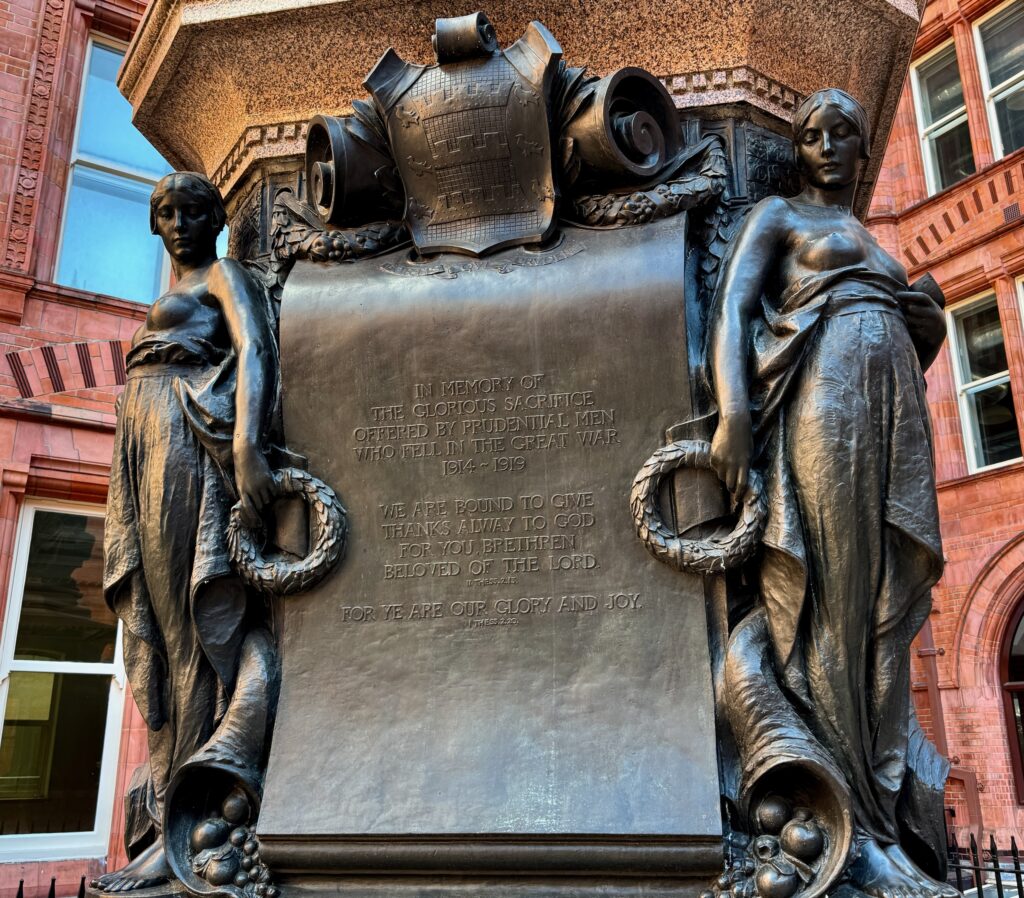

In the courtyard you will see the work of a sculptor who has chosen to illustrate war in a very different fashion to Toft.

The memorial carries the names of the 786 Prudential employees who lost their lives in the First World War …

The sculptor was F.V. Blundstone and the work was inaugurated on 2 March 1922. All Prudential employees had been offered ‘the opportunity of taking a personal share in the tribute by subscribing to the cost of the memorial’ (suggested donations were between one and five shillings).

The main group represents a soldier sustained in his death agony by two angels. He is lying amidst war detritus with his right arm resting on the wheel of some wrecked artillery piece. His careworn face contrasts with that of the sombre, beautiful girls with their uplifted wings. I find it incredibly moving.

I have written about angels in the City before and they are usually asexual, but these are clearly female.

At the four corners of the pedestal stand four more female figures.

One holds a field gun and represents the army …

One holds a boat representing the navy …

At the back is a figure holding a shell representing National Service …

The fourth lady holds a bi-plane representing the air force …

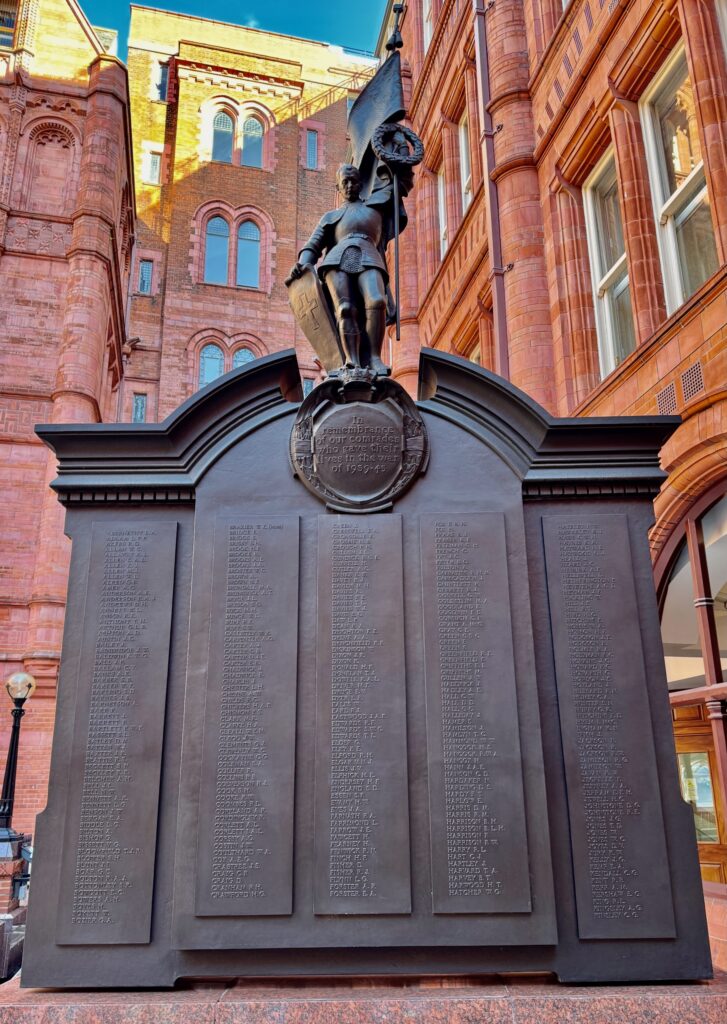

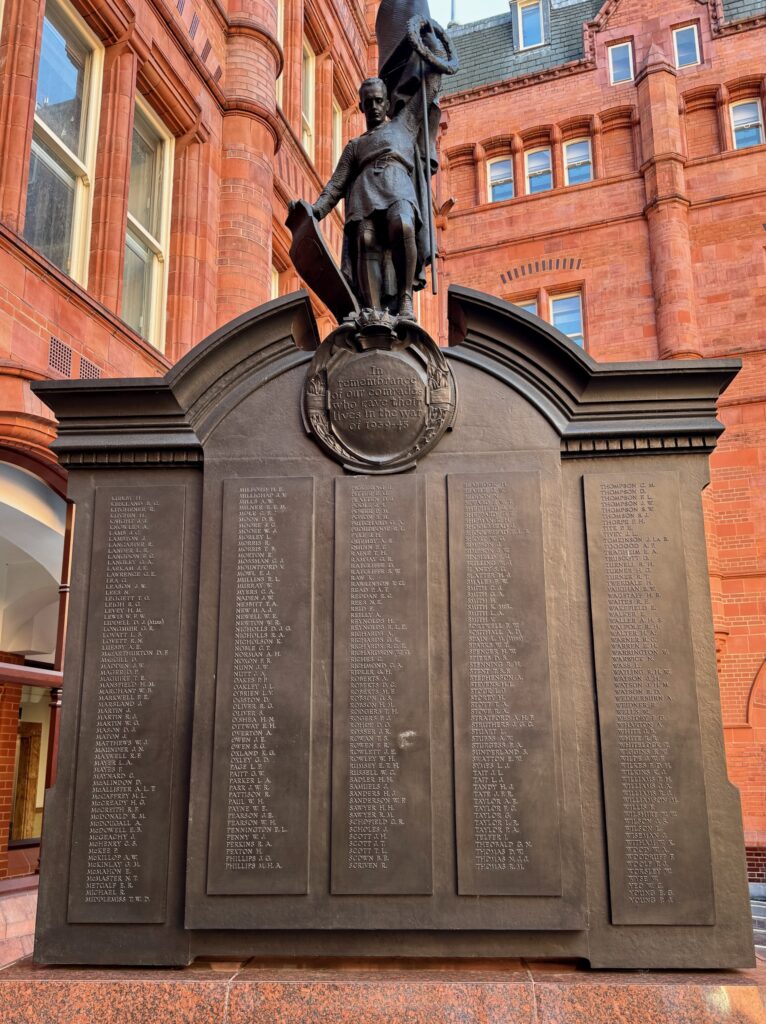

There are also two memorial plaques to employes who died in the Second World War. The north panel lists names A-K, the second K-Z. Each is topped with a broken pediment set around a wreath, with a figure of St George on top …

All those lost lives from just one employer.

I shall probably continue my walk westwards next week.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …