One day in 1936 a young priest officiated at his first funeral – a 14 year old girl who had killed herself because, when her periods started, she thought it was a sign of a sexually transmitted disease. That there seemed to have been no one she could talk to had a profound effect on him, but it was not until 18 years later that, as he put it,

I read somewhere there were three suicides a day in Greater London. What were they supposed to do if they didn’t want a Doctor or Social Worker … ? What sort of a someone might they want?

He looked at his phone, ‘DIAL 999 for Fire, Police or Ambulance’ it said …

There ought to be an emergency number for suicidal people, I thought. Then I said to God, be reasonable! Don’t look at me… I’m possibly the busiest person in the Church of England.

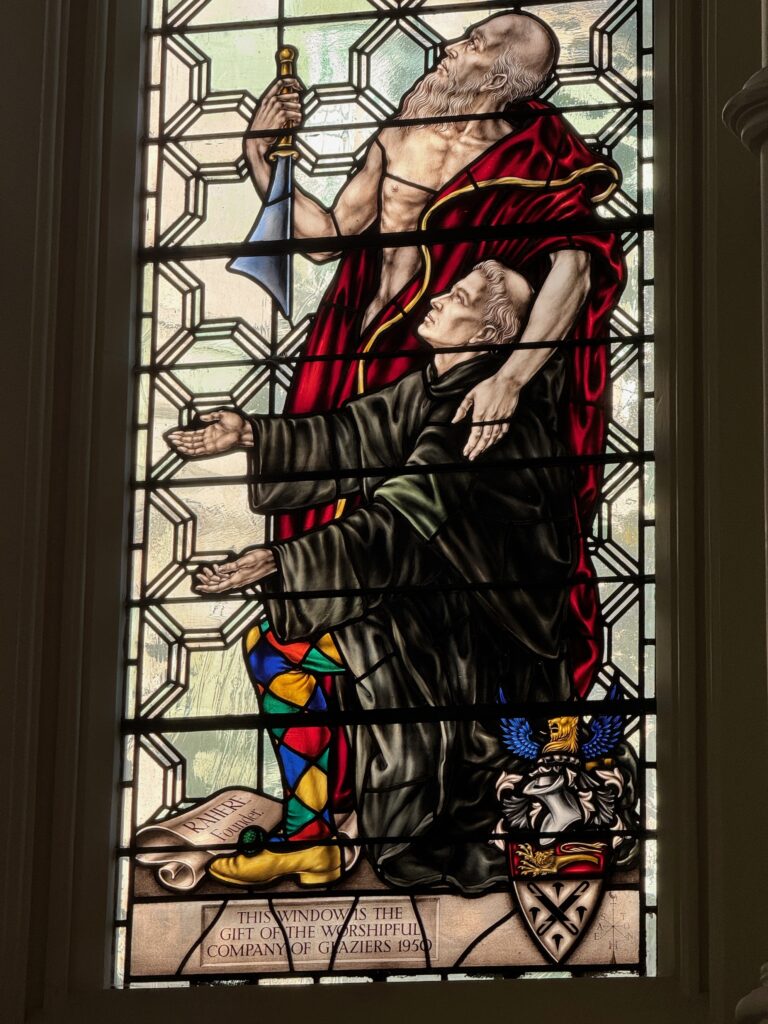

When the priest, Chad Varah, was offered charge of the parish of St Stephen in the summer of 1953 he knew that the time was right for him to launch what he called a ‘999 for the suicidal’. He was, in his own words, ‘a man willing to listen, with a base and an emergency telephone’. The first call to the new service was made on 2nd November 1953 and this date is recognised as Samaritans’ official birthday.

The Reverend Dr Chad Varah at his telephone – you just had to dial MAN 9000.

It soon became obvious that the volunteers, who used to keep people company whilst they were waiting to speak to Chad, were also capable of helping in their own right and in February 1954 he officially handed over the task of supporting the callers to them.

If you visit the church you can see the phone itself …

St Stephen Walbrook (rebuilt 1672-80) was one of Wren’s largest and earliest churches and the meticulous care taken with it might, some suggest, be because Sir Christopher lived next door. Incidentally, Mr Pollixifen, who lived on the other side, bitterly complained about the building taking his light. Maybe he was mollified when the the church’s internal beauty was revealed.

Views towards St Stephen’s have opened up since completion of the new development on Walbrook, which also houses a meticulously restored Temple of Mithras (see my 25th January 2018 blog: The Romans in London – Mithras, Walbrook and the Games).

Looking at the exterior one can see the lovely green Byzantine style dome …

The interior is bright, intimate and stunning, old Victorian stained glass having been removed …

Wren’s dome and Sir Henry Moore’s altar

The dome was the first of its kind in any English church and a forerunner of Wren’s work on St Paul’s Cathedral. After being damaged in the Blitz the church was restored by Godfrey Allen in 1951-52. Controversy broke out when, between 1978 and 1987, the church was re-ordered under the sponsorship of churchwarden Peter (later Lord) Palumbo and a striking ten tonne altar by Sir Henry Moore was placed at its centre.

Sometimes I look at church memorial plaques and, if they are entirely in Latin, just rather lazily move on. In this case it was a big mistake since I was ignoring a tribute to a very brave man …

Dr Nathaniel Hodges’ memorial on the north wall. Photograph: Bob Speel.

The Great Plague of 1665-1666 was the worst outbreak in England for over 300 years and London probably lost getting on for 20% of its population. While 68,596 deaths were recorded in the city, the true number was most likely to be over 100,000. Those who could, usually the professionals and the wealthy, fled the city and this included four-fifths of the College of Physicians. Charles II and his courtiers left in July for Hampton Court and then Oxford where Parliament also relocated in October,

Nathaniel Hodges was a 36-year-old doctor practising in London when the pestilence reached the City. London was awash, he said later, with ‘Chymists’ and ‘Quacks’ dispensing, as he put it: ‘… medicines that were more fatal than the plague and added to the numbers of the dead.’

Dr Hodges decided to stay and minister to the sick and dying.

First thing every morning before breakfast he spent two or three hours with his patients. He wrote later …

Some (had) ulcers yet uncured and others … under the first symptoms of seizure all of which I endeavoured to dispatch with all possible care …

hardly any children escaped; and it was not uncommon to see an Inheritance pass successively to three or four Heirs in as many Days.

After hours of visiting victims where they lived he walked home and, after dinner, saw more patients until nine at night and sometimes later.

He survived the epidemic and wrote two learned works on the plague. The first, in 1666, he called An Account of the first Rise, Progress, Symptoms and Cure of the Plague being a Letter from Dr Hodges to a Person of Quality. The second was Loimologia, published six years later …

The above is a later edition of Dr Hodges’ work, translated from the original Latin and published when the plague had broken out in France.

It seems particularly sad to report that his life ended in personal tragedy when, in his early fifties, his practice dwindled and fell away. Finally he was arrested as a debtor, committed to Ludgate Prison, and died there, a broken man, in 1688.

Translated from the Latin, his memorial reads as follows:

Learn to number thy days, for age advances with furtive step, the shadow never truly rests. Seeking mortals, born that they might succumb, the executioner comes from behind. While you breathe you are a victim of death; you know not the hour in which your fate will call you. While you look at monuments, time passes irrevocably. In this tomb is laid the physician Nathaniel Hodges in the hope of heaven; now a son of earth, who was once a son of Oxford. May you survive the plague by his writings. Born 13 September AD 1629 Died 10 June 1688.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …