What better place and person to start with than the Tower of London and William I (a.k.a ‘The Conqueror’ and ‘The Bastard’).

As everyone knows, he invaded England and defeated King Harold at the battle of Hastings in 1066. His reign is primarily remembered for the compilation of the Domesday Book in 1086 and for the building of many castles.

The castle which later became known as the Tower of London was begun in 1066 and was originally a timber fortification enclosed by a palisade. In the next decade work began on the White Tower, the great stone keep that still dominates the castle today …

William was keen to keep the City of London placated and not to disrupt commerce. In order to do this, after his coronation but before he entered the City, he issued the William Charter.

Written on vellum (parchment) in Old English, it measures just six inches by one-and-a-half inches …

Translated into modern English, the Charter reads as follows:

‘William the king, friendly salutes William the bishop and Godfrey the portreeve and all the burgesses within London both French and English. And I declare that I grant you to be all law-worthy, as you were in the days of King Edward; And I grant that every child shall be his father’s heir, after his father’s days; And I will not suffer any person to do you wrong; God keep you.’

City of London historians point out that one of the citizens’ primary concerns, as expressed by the words – “And I grant that every child shall be his father’s heir, after his father’s days” – was to ensure that their property handed down to the son and heir, rather than attracting the interest of the Crown.

Here he is as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry …

There are two main accounts of his death in 1087. While some vaguely state that he became ill on the battlefield, collapsing through heat and the effort of fighting, William of Malmesbury added the gruesome detail that William’s belly protruded so much that he was mortally wounded when he was thrown onto the pommel of his saddle. Since the wooden pommels of medieval saddles were high and hard, and often reinforced with metal, William of Malmesbury’s suggestion is a plausible one. There’s a witty article about William’s demise here in the journal Historic UK.

William was followed as king by his third son, also called William but commonly called Rufus because of his ruddy complexion and red hair. The gossipy William of Malmsbury hinted that the King was homosexual since he surrounded himself with young men who ‘rival young women in delicacy’. Here he is as illustrated in the miniature from Historia Anglorum, c. 1253 …

Whilst hunting in the New Forest on 2 August 1100 he was accidentally killed by an arrow from one of his own men …

A relic of Rufus’s time is the crypt of St Mary-le-Bow which I wrote about a few weeks ago. I wonder if any of Rufus’s ‘delicate’ young men ever walked down these beautifully worn steps …

You will find some very interesting history and more images in the crypt Conservation and Management Plan of 2007.

William II was followed on the throne by his youngest brother, Henry. He was crowned three days after his brother’s death (3rd August 1100) against the possibility that his eldest brother Robert might claim the English throne on his imminent return from the Crusade. His life was blighted in 1120 when the ‘White Ship’ bearing both his sons sank in the channel. This is a 13th century depiction of the tragic event …

Subsequently he made his barons swear to accept his daughter, Matilda, as his heir. Henry died on 2nd December 1135 from ‘a surfeit of lampreys’ – probably food poisoning.

For a sense of Henry’s time, make a visit to the church of St Bartholomew the Great.

St Bartholomew’s was established by Rahere, a courtier and favourite of the king. It is thought that it was the death of the Henry’s wife, Matilda, followed two years later by the White Ship drownings, that prompted Rahere to renounce his profession for a more worthy life and make his pilgrimage to Rome.

In Rome, like many pilgrims, he fell ill. As he lay delirious he prayed for his life vowing that, if he survived, he would set up a hospital for the poor in London. His prayers were answered and he recovered. As he turned for home the vision of Saint Bartholomew appeared to him and said “I am Bartholomew who have come to help thee in thy straights. I have chosen a spot in a suburb of London at Smoothfield where, in my name, thou shalt found a church.”

True to his word Rahere set up both a church, a priory of Augustinian canons, and the hospital. He lived to see their completion – indeed he served as both prior of the priory and master of the hospital – and it is possible that he was nursed at Barts before his death in 1145. His tomb lies in the church.

You get a nice view of the flint and Portland Stone western facade of the church from the raised churchyard. An old barrel tomb rests in the foreground …

Bear in mind that the original church was vast and also covered the area now occupied by the graveyard and the path. This used to be the nave, as illustrated in this plan on display in the church …

Stepping into the church seems to transport you to another time and place …

The patchworked exterior gives no hint of the stunning Romanesque interior, with its characteristic round arches and sturdy pillars. It’s a rare sight in London; indeed, this is reckoned to be the best preserved and finest Romanesque church interior in the City. I visited it back in 2020 and you can read the blog here.

Nearby is this impressive statue of Henry VIII over the main entrance to St Bartholomew’s hospital, the only outdoor statue of the king in London. If you have seen and admired the famous Holbein portrait, the king’s pose here is very familiar. He stands firmly and sternly with his legs apart, one hand on his dagger, the other holding a sceptre. He also sports an impressive codpiece …

Bart’s, as it became known affectionately, was put seriously at risk in 1534, when Henry VIII commenced the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The nearby priory of St Bartholomew was suppressed in 1539 and the hospital would have followed had not the City fathers petitioned the king and asked for it to be granted back to the City. Their motives were not entirely altruistic. The hospital, they said, was needed to help:

the myserable people lyeing in the streete, offendyng every clene person passyng by the way with theyre fylthye and nastye savors.

Henry finally agreed in December 1546 on condition that the refounded hospital was renamed ‘House of the poore on West Smithfield in the suburbs of the City of London, of King Henry’s foundation’. I suspect people still tended to call it Bart’s.

You can see the agreement document, along with Henry’s signature, in the hospital museum …

It also bears Henry’s seal, the king charging into battle on horseback accompanied by a dog …

The King finally got full public recognition when the gatehouse was rebuilt in 1702 and his statue was placed where we still see it today. The work was undertaken and overseen by the mason John Strong, who was at the same time working for Sir Christopher Wren on St Paul’s Cathedral. Such were the masons’ talents, no architectural plans were needed to complete the work.

And finally, poor Queen Anne, whose statue stands outside St Paul’s Cathedral.

Wearing a golden crown, she has the Order of St George around her neck, a sceptre in her right hand and the orb in her left.

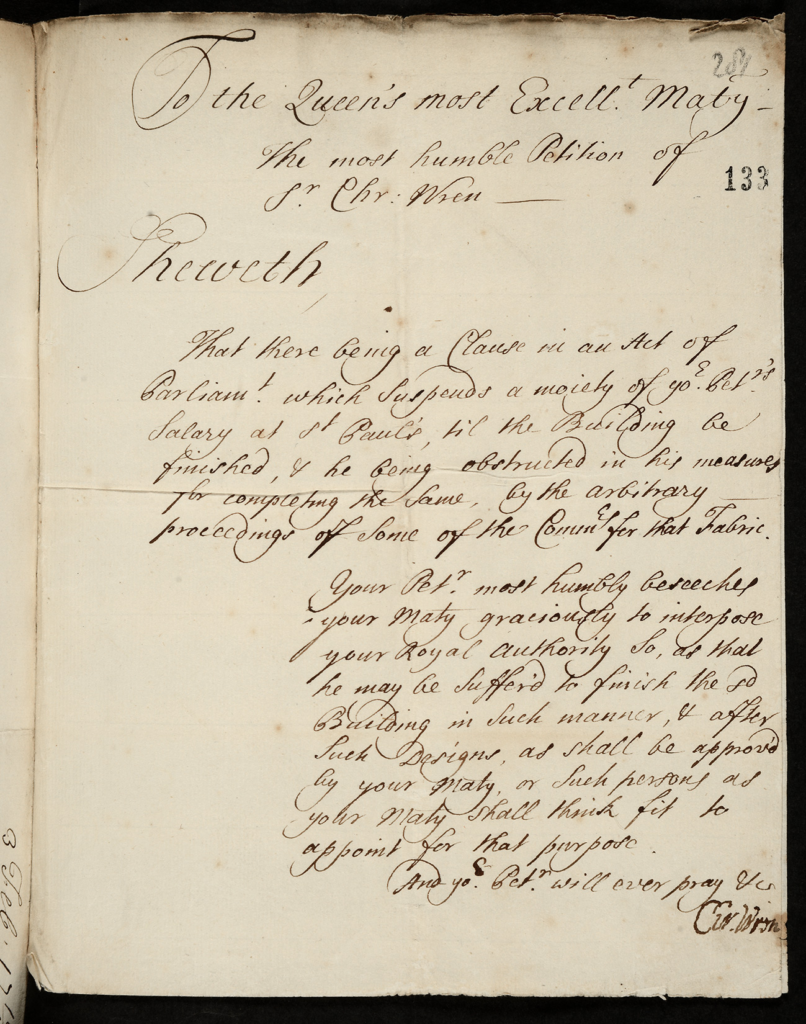

She was close to the architect, the brilliant Christopher Wren, who wrote to her to ask her to help when his salary was being witheld and his work obstructed …

The letter is held in the National Archives SP34/29 f 133.

It’s difficult not to feel sorry for Anne. Her personal life was marked by the tragedy of losing 18 children (including twins) through miscarriage, stillbirth and early death. Two of her daughters, Mary and Anne Sophia, died within days of each other, both aged under two years, of smallpox in 1687.

Anne was 37 years old when she became queen in 1702. At her coronation she was suffering from a bad attack of gout and had to be carried to the ceremony in an open sedan chair with a low back so that her six-yard train could pass to her ladies walking behind. Her medical conditions made her life very sedentary and she gradually put on a lot of weight. She died after suffering a stroke on Sunday 1st August 1714 at the age of 49. You can read much more about her in my blog Queen Anne – tales of tragedy, love and vandalism.

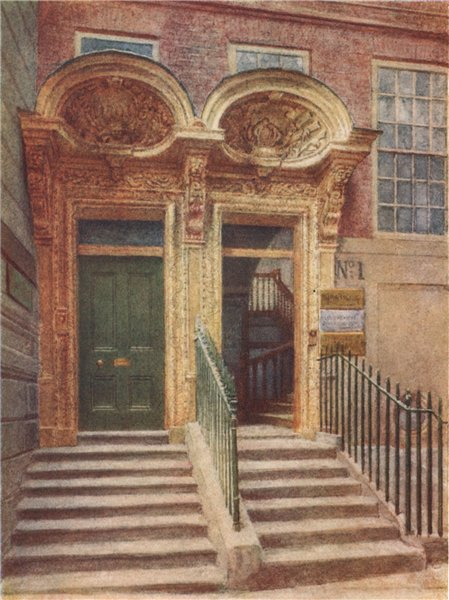

For a glimpse of the architecture of her time there are no finer City examples than 1 and 2 Laurence Pountney Hill …

They were built in 1703 as a pair of red brick, four-storey houses, on the site of a single post-fire house. They are considered to be finest surviving houses of this period in the City with elaborately carved foliage friezes around the doors and cornice above and ornate shell-hoods over the doorways. The virtuosity of the woodwork is explained by the fact that the houses were built by a master carpenter, Thomas Denning. He had worked on Wren’s church of St Michael Paternoster Royal nearby and would later contribute to Hawksmoor’s St Mary Woolnoth. Like other ambitious craftsmen, Denning branched out into the cut throat world of speculative building. At Laurence Pountney Hill he appealed to the market by ingeniously contriving two basements beneath the houses. This created an abundance of storage space that would be attractive to the London merchants, whose houses doubled as business premises. Denning’s speculation paid off; on 15 July 1704 he sold both houses to Mr John Harris for £3,190, a tidy sum.

The delightful doorway hoods. Look closely – the cherubs on the right are playing bowls!

Here is a close-up (you may have to concentrate – they are not always obvious) …

The date is still visible despite years of over-painting …

The buildings in 1905 with the door to number 1 open revealing the lovely original curved staircase …

There are other fine architectural examples of the period in the very appropriately named Queen Anne’s Gate in Westminster …

The lady herself has a statue there …

When I worked nearby I was told that, at midnight on her birthday, she would step off her plinth and promenade along the street inspecting the houses. The statue has an interesting history which you can read about here.

There is also a fascinating description of the street’s cannopies and carvings in the excellent London Inheritance blog.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …