Today I’m continuing the walk I started last week heading south along City Road.

Just before the Old Street roundabout you encounter two intriguing buildings. The first of these is The Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms …

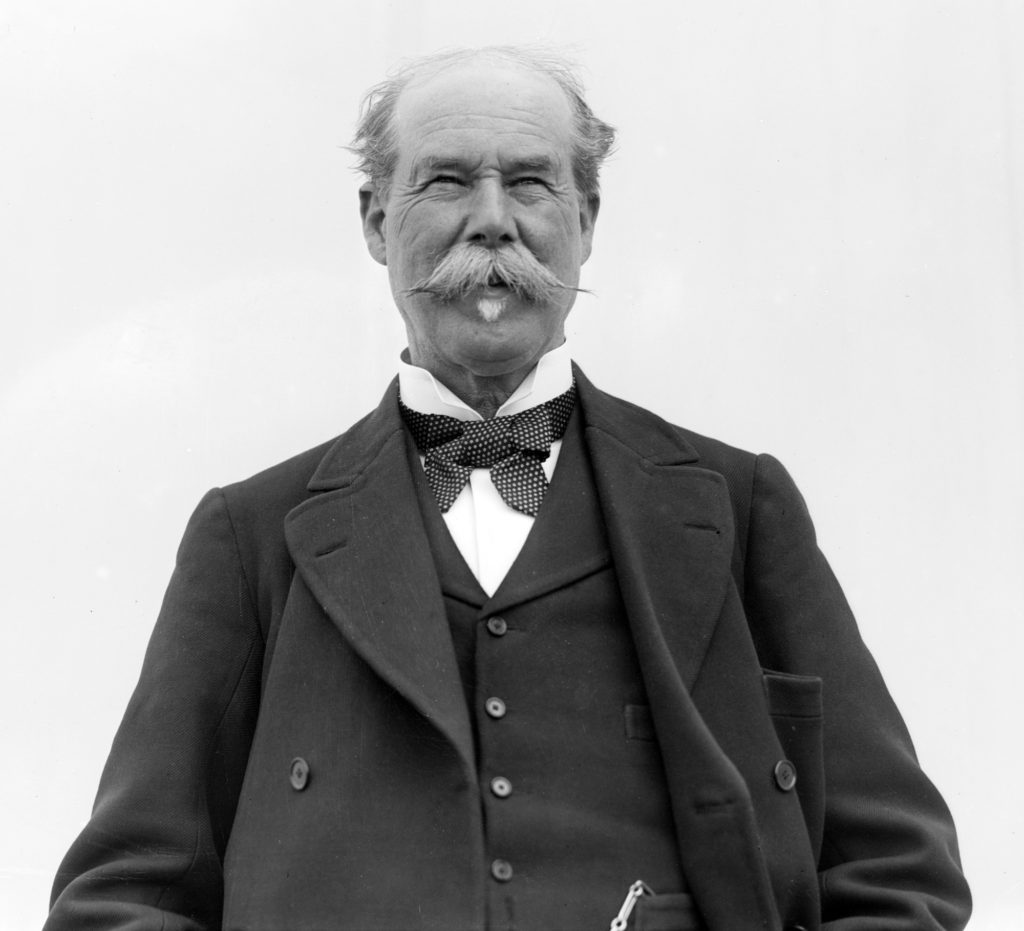

In August 1898, newspapers reported a plan to provide cheap meals at cost price in a series of counter-service restaurants in the poorest parts of London. Sir Thomas Lipton, wealthy grocer and philanthropist, was prepared to spend £100,000 on building them; after the initial outlay the scheme aimed to be self-supporting. HRH the Princess of Wales – Princess Alexandra, wife of the future King Edward VII – lent her patronage. The scheme built on her Diamond Jubilee meal for the poor in 1897, for which the then Mr. Lipton had donated £25,000 of the required £30,000, and which succeeded in feeding 300,000 people. He was knighted at the start of 1898, made a Baron in 1902 and died in 1931 aged 83. A fine man with a fine moustache …

Called Empire House, the Old Street building opened on the 9th of March 1900. It had three floors of dining rooms each designed to hold 500 people – a number frequently exceeded in later years. The Morning Post reported that the basement included washing facilities for customers and an artesian well yielding 2,000 gallons of water an hour, and that 1,200 steak puddings can be cooked simultaneously. There were ‘electric automatic lifts’ to aid distribution of food to the dining floors, and a bakehouse with electric kneading. The Sketch described the establishment as a type of slap-bang – an archaic noun meaning a low eating house. Soup, steak pudding with two vegetables and a pastry costs 4½ᵈ.

The kitchen …

The men’s dining room …

The ladies’ dining room …

The Dining Rooms closed in 1951. You can read the full history of this fascinating enterprise here on the brilliant London Wanderer blog.

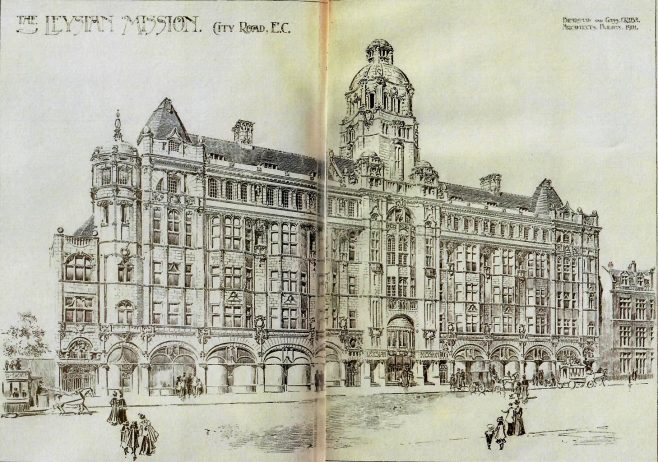

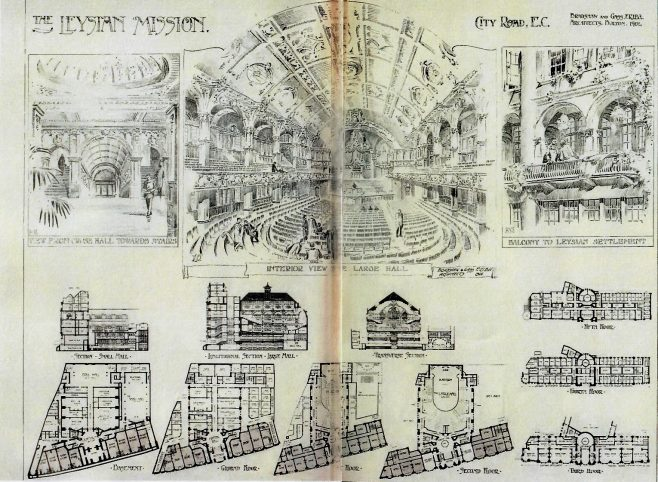

Further south is the stunning terracotta masterpiece that was once the Leysian Mission …

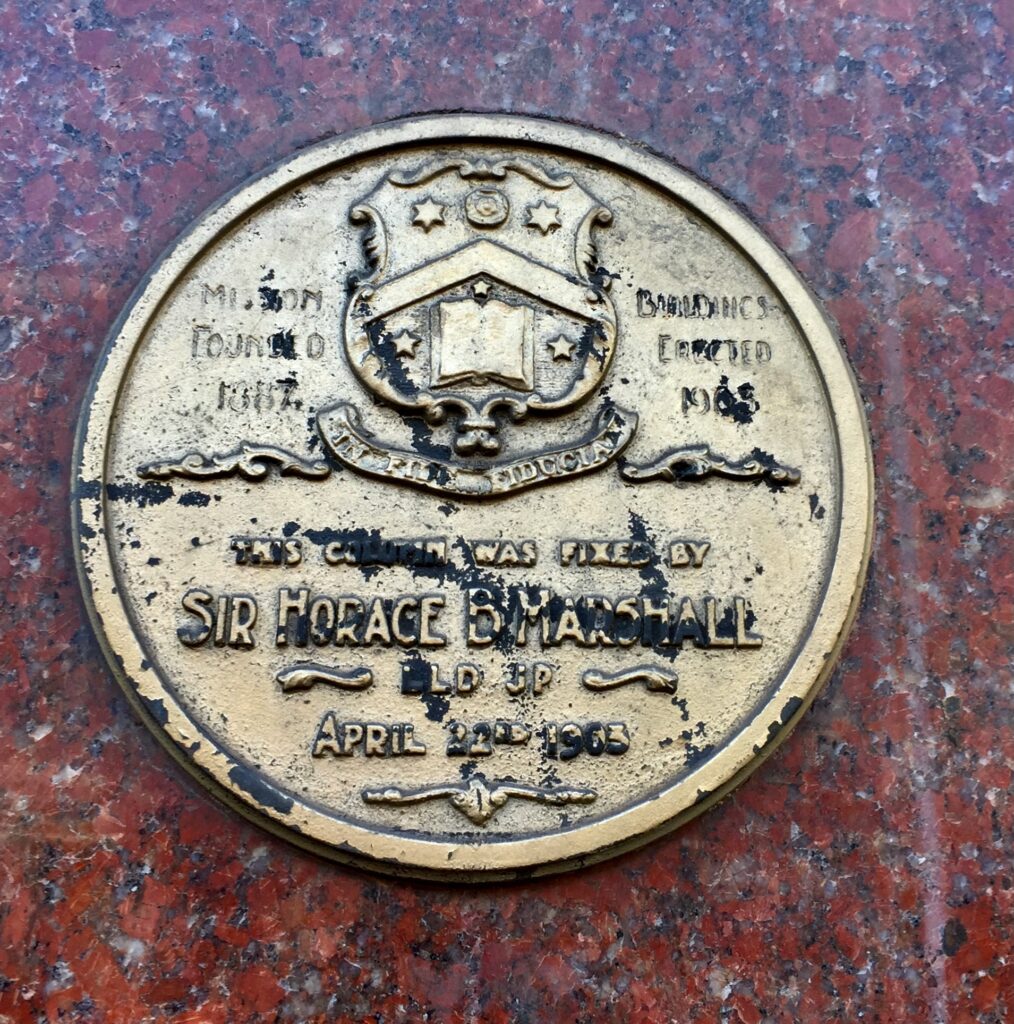

The crest above the main entrance bears the Latin words ‘In Fide Fiducia’ (In Faith, Trust), which is the motto of the Leys School in Cambridge. The object of the Mission organization was to promote the welfare of the poorer people in the UK …

At the dawn of the last century, like the Dining Rooms, the Leysian Mission was a welfare centre for the poor masses of the East End. As well as saving people’s souls, the Methodists who ran it believed in helping people in this life too. They thus offered health services, a ‘poor man’s lawyer’, entertainment in the form of film screenings and lantern shows, as well as hosting affiliated organisations such as the Athletic Society, the Brass Band, the Penny Bank, the Working Men’s Club and Moulton House Settlement for Young Men …

The Methodist meeting places ‘were all built to look as un-churchlike as possible in an attempt to woo the working classes away from the temptations of drink and music halls.’ The building’s Great Queen Victoria Hall, which seated nearly 2,000 people, boasted a magnificent organ as well as a stunning stained glass window.

Plans published in The Building News 1901 …

The combination of the Second World War, during which the building suffered extensive bombing damage, followed by the introduction of the welfare state and the changing social character of the area saw the Leysian Mission gradually lose its relevance as a welfare centre. In the 1980s it merged with the Wesleyan Church with the building sold, converted into residential flats and renamed Imperial Hall.

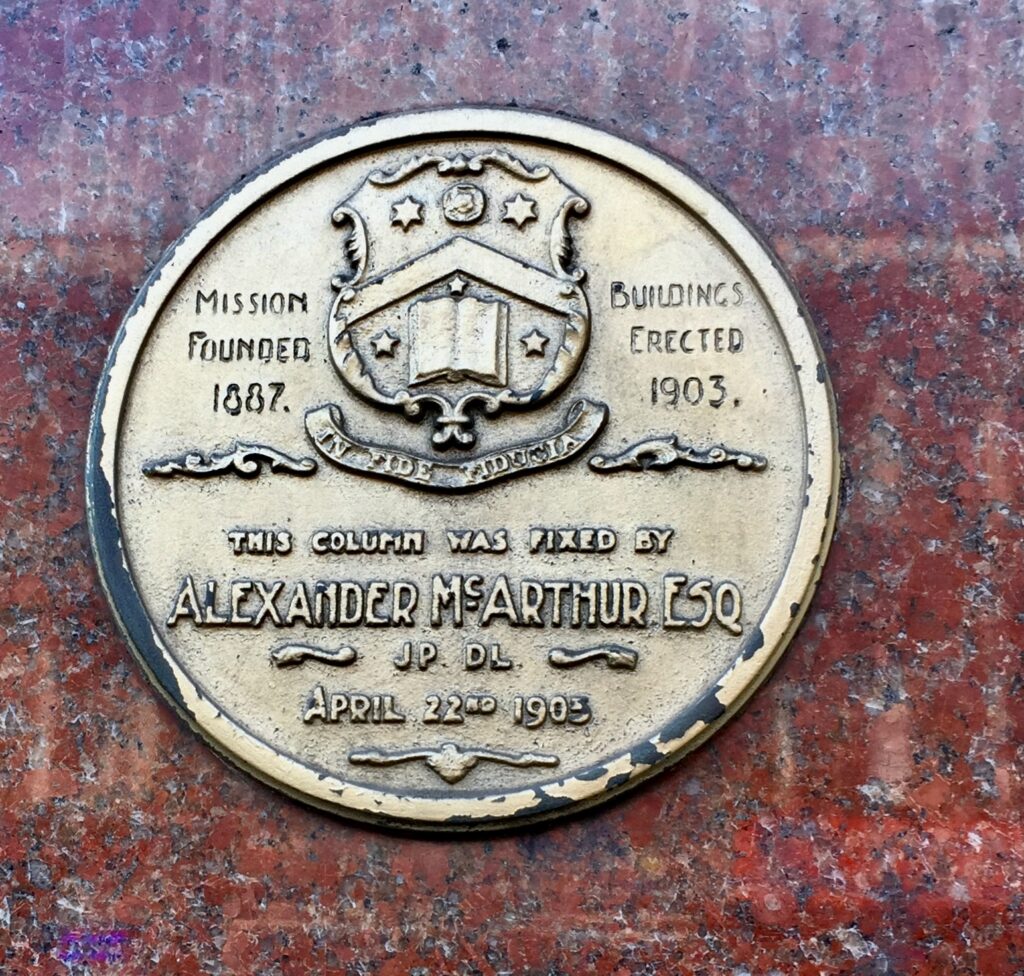

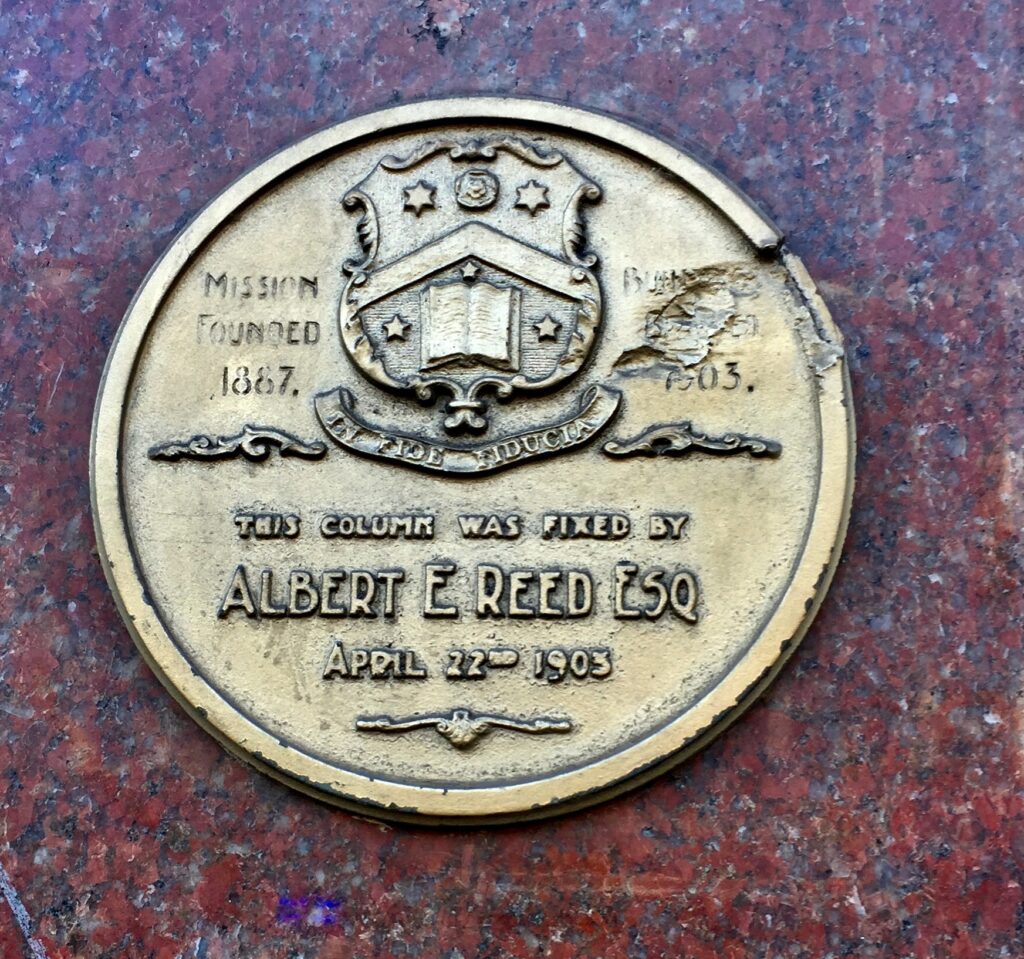

Plaques that were ‘fixed’ by VIPs when the building was completed in 1903 are still there …

I like the posh brass intercom system …

At the roundabout there’s another plaque, this time commemorating the City Road Turnpike …

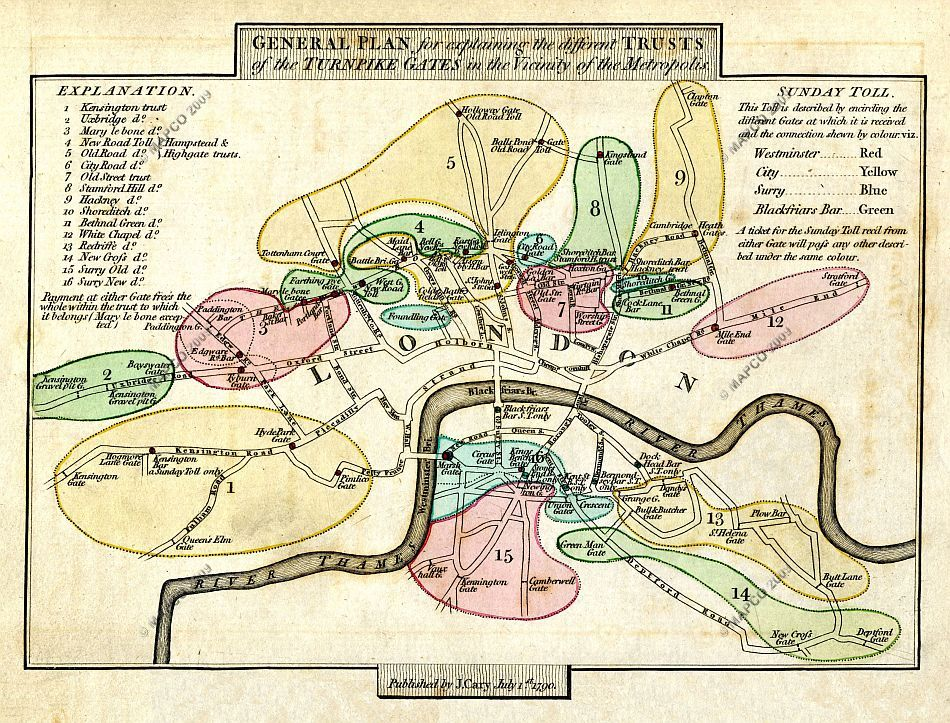

Road pricing is not new! Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the capital operated an extensive system of toll gates, known as turnpikes, which were responsible for monitoring horse-drawn traffic and imposing substantial charges upon any traveller wishing to make use of the route ahead.

A ‘General Plan For Explaining The Different Trusts Of The Turnpike Gates In The Vicinity Of The Metropolis. Published By J. Cary, July 1st, 1790’ …

Just like today, certain lucky users were exempt from the charge – namely mail coaches, soldiers, funeral processions, parsons on parish business, prison carts and, of course, members of the royal family.

Vandals today damaging or destroying ULEZ cameras can feel something in common with these people – a ‘rowdy group of travellers causing trouble at a turnpike in 1825’ …

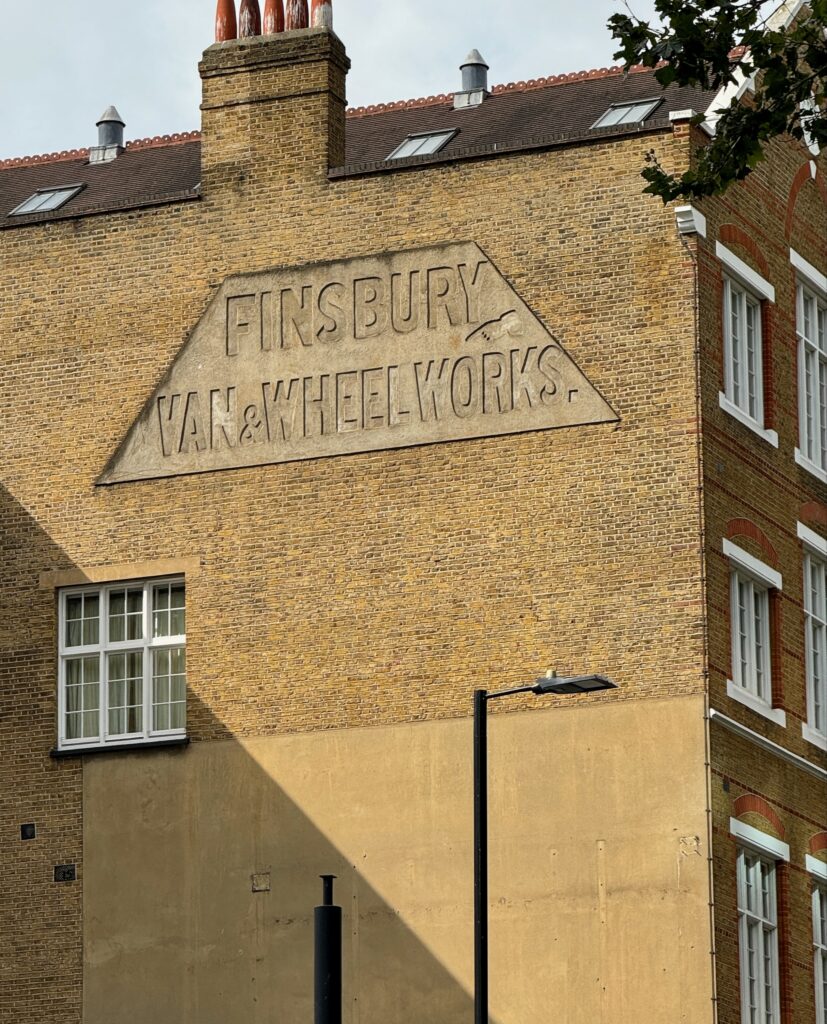

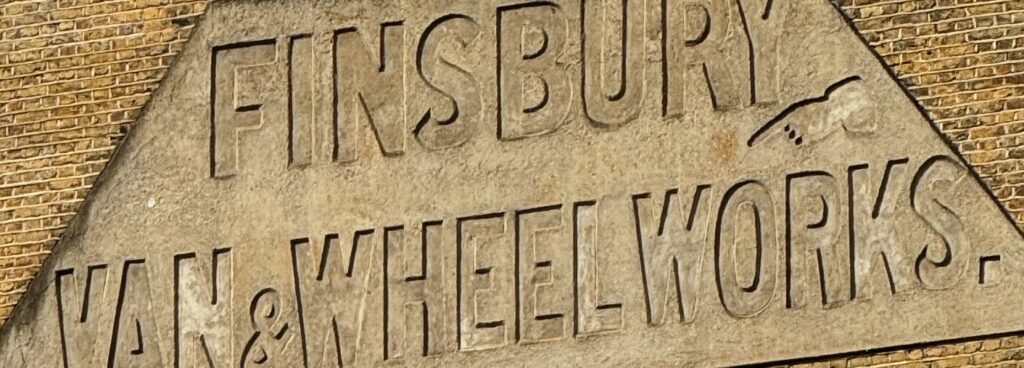

As you cross the road by the roundabout, look west along Old Street and you’ll see a magnificent old sign, a relic of the area’s industrial past. An extract from the blog of the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society reads as follows:

‘It is pleasing to discover that last year the sign, which is thought to date from early in the 20th century, was restored (though without the black paint Bob thought might originally have featured) and now looks very good. It was presumably erected by J Liversidge and Son, wheelwrights and later wagon and van builders, who occupied 196 Old Street for some decades. The firm first appears in the Old Kent Road in the 1880s; by the 1890s they had expanded into Hackney and then into Old Street. By 1921 they were back in the Old Kent Road alone, the development of motor vehicles presumably having removed much of their busines’ …

I like the hand pointing down to the site (it’s now a petrol station) …

It’s on the east wall of what was once St Luke’s School who presumably made an appropriate charge for allowing its installation …

I paused to admire Old Street Station’s green roof …

Just past the roundabout on the left there’s a building that’s a bit of a mystery. It’s almost opposite the entrance to the Bunhill Burial Ground and has been derelict for as long as I can remember (and that’s quite a while) …

Very strange. On the north wall is a plaque bearing the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, so maybe they own the building …

I thought it would be appropriate on this walk to acknowledge the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, and pop in for a brief visit to his chapel …

It’s well worth a diversion.

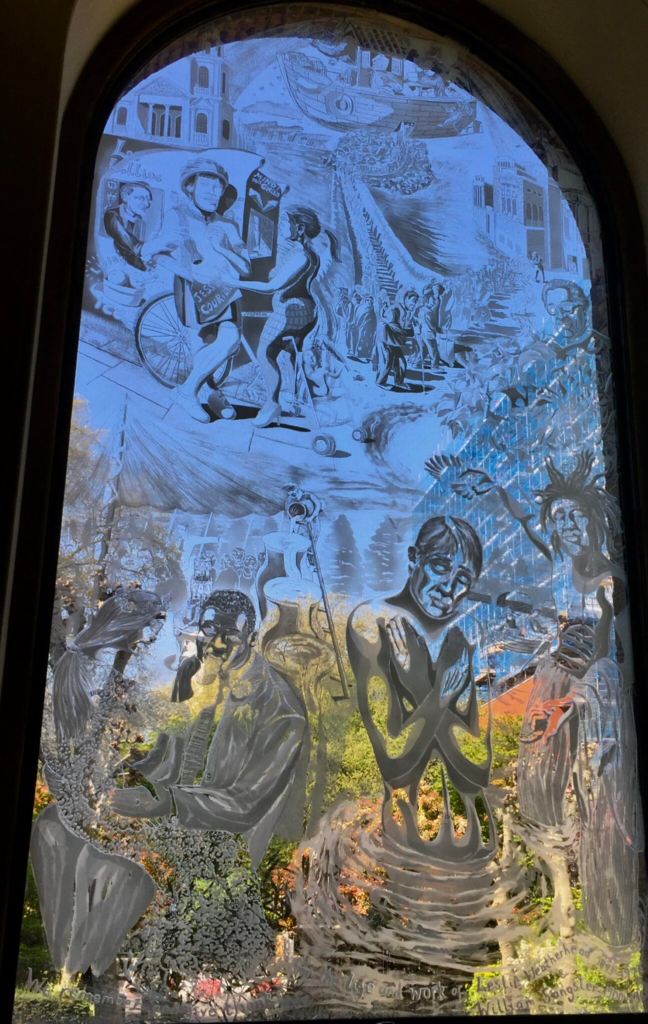

You can admire the stained glass of which there are many fine traditional examples …

Plus some striking, unusual contemporary works …

Margaret Thatcher (then Margaret Roberts) married Denis Thatcher here on 13 December 1951 and both their children were christened here. She donated the communion rail in 1993 …

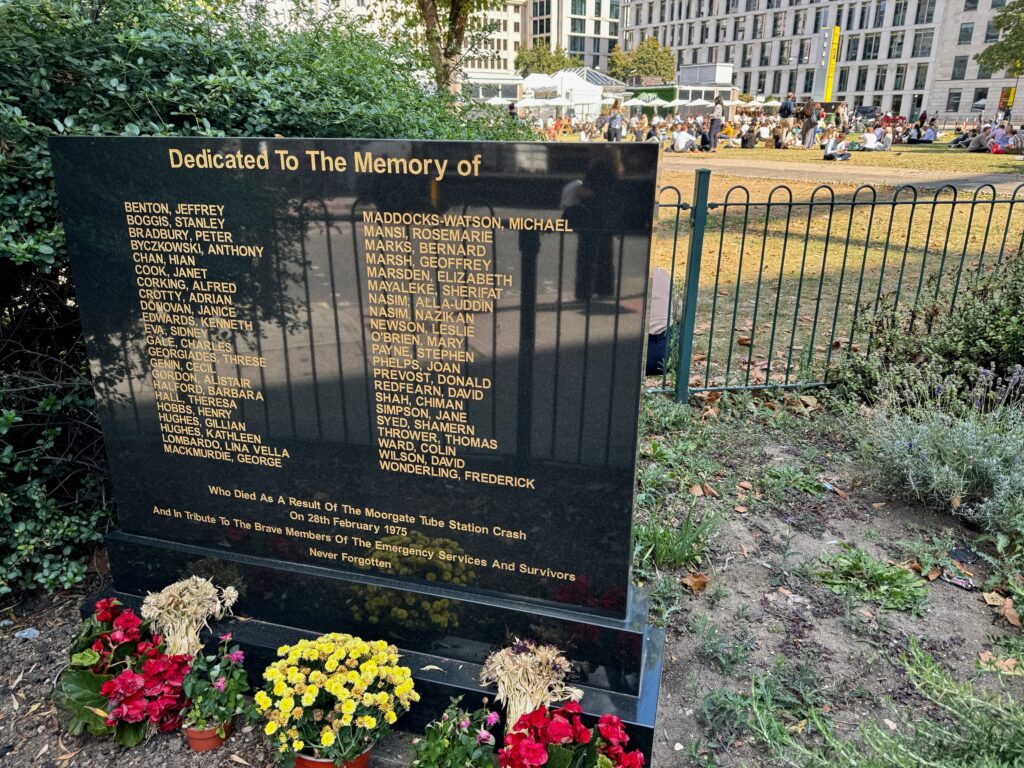

On 28 February 1975 at 8:46 am at Moorgate Station 43 people died and 74 were injured after a train failed to stop at the line’s southern terminus and crashed into its end wall. No fault was found with the train, and the inquiry by the Department of the Environment concluded that the accident was caused by the actions of Leslie Newson, the 56-year-old driver. A memorial tablet was placed in Finsbury Square …

Mr Newson is commemorated on the memorial along with the others who lost their lives. There has never been a satisfactory explanation for his behaviour, but suicide seemed unlikely. Newson was known by his colleagues as a careful and conscientious motorman (driver). On 28 February he carried a bottle of milk, sugar, his rule book, and a notebook in his work satchel; he also had £270 in his jacket to buy a second-hand car for his daughter after work. According to staff on duty his behaviour appeared normal. Before his shift began he had a cup of tea and shared his sugar with a colleague; he jokingly said to the colleague “Go easy on it, I shall want another cup when I come off duty”.

It took all day to remove the injured, many of whom had to be cut free. After five more days and an operation involving 1,324 firefighters, 240 police officers, 80 ambulance workers, 16 doctors and numerous volunteers all of the bodies were recovered. The driver’s body was taken out on day four. His crushed cab, at the front of the train, normally 3-foot deep, had been reduced to 6 inches.

On the north side of the square is this building …

Formerly Triton Court, it’s now known as the Alphabeta Building. Many years ago I would sometimes travel by train into the now demolished Broad Street Station. As the train approached the terminus I could see from my carriage what looked like a little boy standing on a large ball at the very top of the building. It looked like he was waving at me!

Well, he’s still there …

Now, however, I know the statue standing on top of the globe is Mercury (Hermes) the messenger and God of profitable trade. It’s by James Alexander Stevenson and was completed in the early 1900s. Though it would be impossible to see from the ground it’s apparently – as with all Stevenson’s work – signed with ‘Myrander’ a combination of his wife’s name (Myra) and his middle name (Alexander). Sweet. The renovated building is quite stunning inside as you can see here.

And finally to Moorgate Station, where a relic of its past life can be seen if you glance from across the road to the east facing entrance …

It’s a version of the logo of the City and South London Railway (C&SLR) adapted to show the carriages passing through a tunnel under the Thames where little boats bob about in the water. And for extra authenticity, I think the train on the right is coming towards us and the one on the left moving away. I love it …

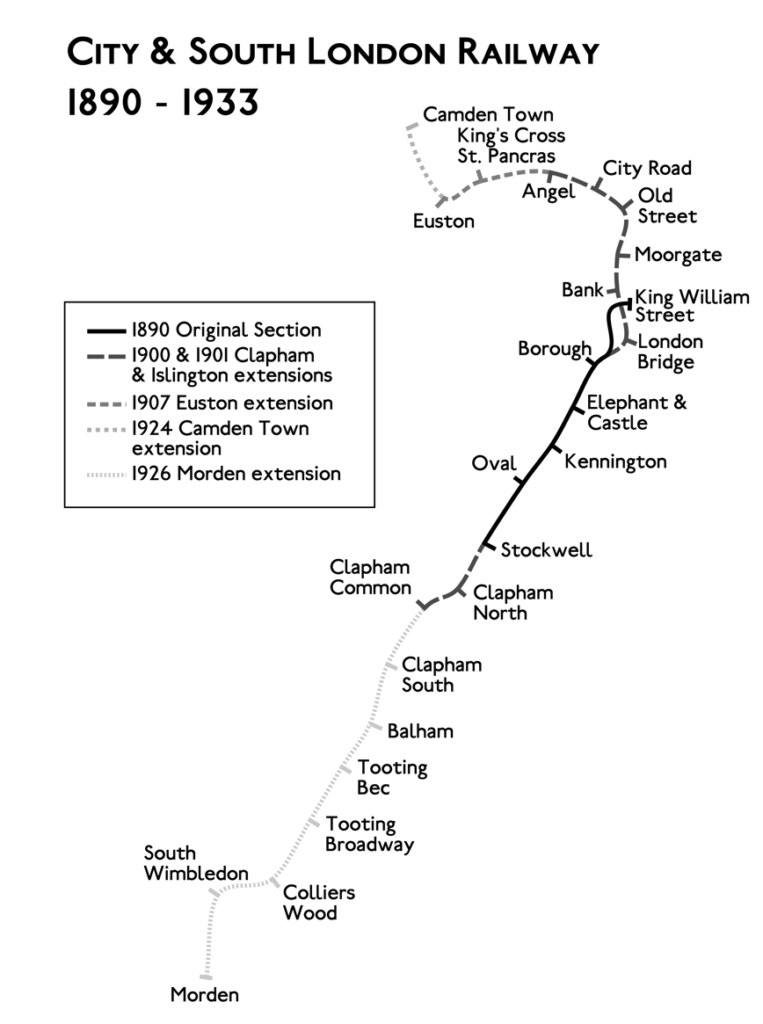

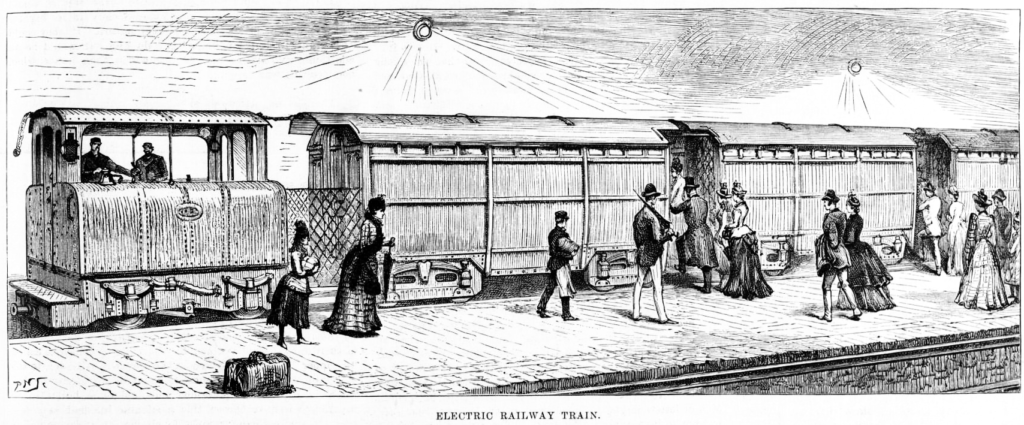

This was the first successful deep-level underground ‘tube’ railway in the world and the first major railway to use electric traction …

The original service was operated by trains composed of an engine and three carriages. Thirty-two passengers could be accommodated in each carriage, which had longitudinal bench seating and sliding doors at the ends, leading onto a platform for boarding and alighting. It was reasoned that there was nothing to look at in the tunnels, so the only windows were in a narrow band high up in the carriage sides. Gate-men rode on the carriage platforms to operate the lattice gates and announce the station names to the passengers. Because of their claustrophobic interiors, the carriages soon became known as padded cells …

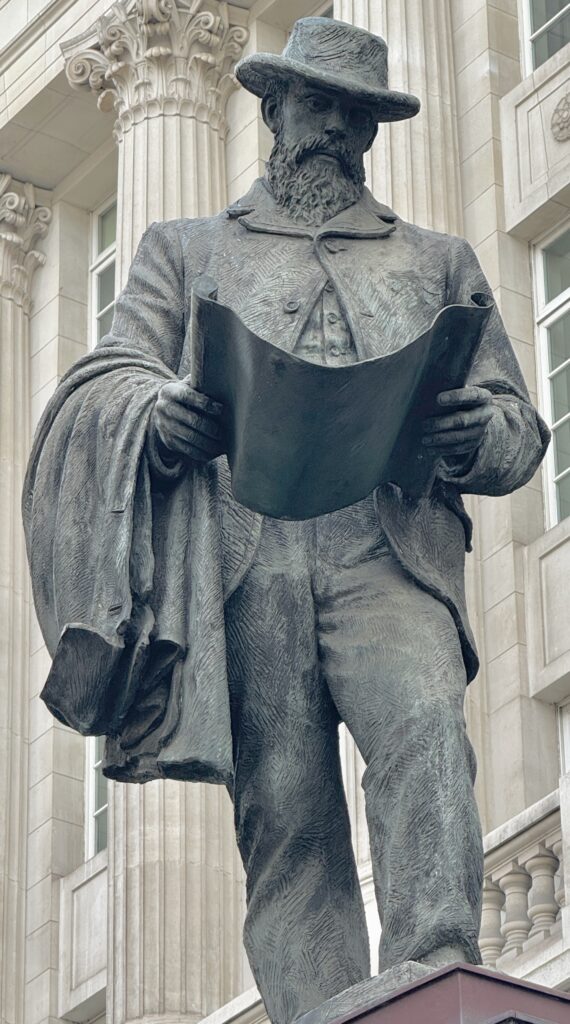

The genius behind deep tunnel boring was James Henry Greathead, a South African engineer (note the hat) who invented what was to become known as the Greathead Shield. His statue, below, was placed on Cornhill because a new ventilation shaft was needed for Bank Underground Station and it was decided that he should be honoured on the plinth covering the shaft …

It was such a nice sky I took another image which also shows the C&SLR logo incorporated in the plinth …

You can read more about him and his tunnelling innovation in my blog City work and public sculpture. You can also read the full fascinating history of the City and South London Railway here.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …