… That’s the way the money goes, Pop! goes the weasel’.

After Googling this very old rhyme, I was bewildered by the number of interpretations of the term ‘Pop goes the weasel’! Anyway, here’s the one I like best:

‘In the mid-19th century, “pop” was a well-known slang term for pawning something—and City Road had a well-known pawn establishment in the 1850s. In this Cockney interpretation, “weasel” is Cockney rhyming slang for “weasel and stoat” meaning “coat”. Thus, to “pop the weasel” meant to pawn your coat’.

Presumably this was done to spend money on drink in The Eagle pub, and I shall be walking past The Eagle in this week’s blog as I walk down City Road.

My walk starts, however, at the corner of Golden Lane and Beech Street with the Banksy artwork that pays tribute to Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) whose UK retrospective opened at the Barbican Centre on 21 September 2017. The main work features a stencilled policeman and woman, recognisably Banksy, who appear to be conducting a stop and search on the artist …

On the other side of the street is a smaller piece, this time featuring a stencilled ferris wheel with people queuing to enter. The carriages have been replaced with stylised crowns, the symbol of Basquiat himself and now an iconic image in the street art and graffiti world …

Heading north I came across this rather nice Victorian double post box …

One of the slots would have been for ‘Meter Mail’ in which businesses once sent pre-printed, self-addressed envelopes or packages to customers with postage pre-paid in-house using a postage meter.

It was made by the founder Andrew Handyside (1805-1887) …

The company was a prolific manufacturer but after Handyside died in 1887 the firm gradually declined until it closed early in the twentieth century.

Here’s the man himself (National Galleries of Scotland) …

A few yards further is the famous Golden Lane Estate …

In the middle of the nineteenth century, over 130,000 people resided in the City of London but by 1952 that number had dropped to just 5,000. Business and commerce had become the main uses of land in the City. Residents who had lost their homes as a result of the 2nd World War bombings were re-housed in areas outside the centre. However, the City Corporation was concerned about the depopulation of the City and turned its attention to this when planning the rebuilding of the City in the post-war era.

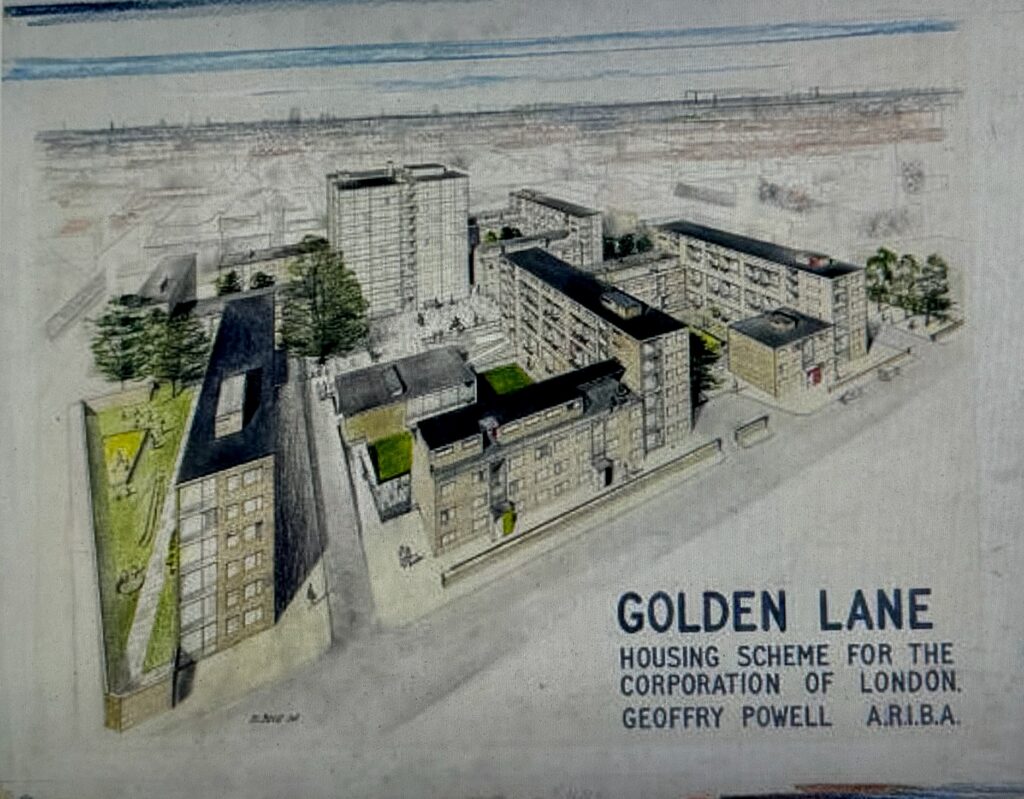

The Corporation announced the competition to design an estate

at Golden Lane on 12 July 1951 with the closing date for submissions on 31 January 1952. It was won by Geoffry Powell, a lecturer in architecture at the Kingston School of Art College, in 1952. He invited lecturer colleagues Christoph Bon and Joseph Chamberlin to join him in developing a

detailed design for the Golden Lane Estate. You can read an interesting history of the estate and its design here.

The winning entry …

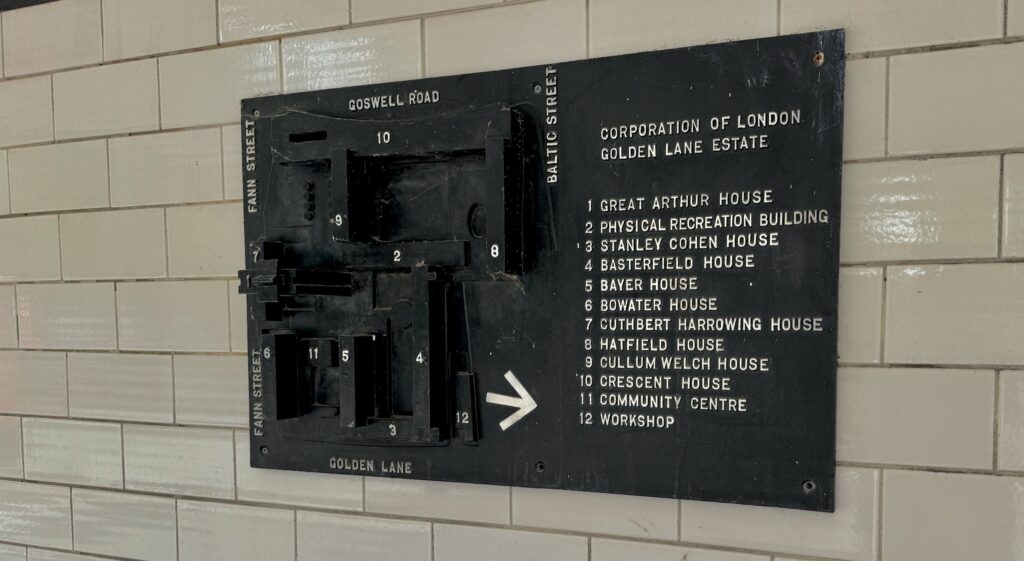

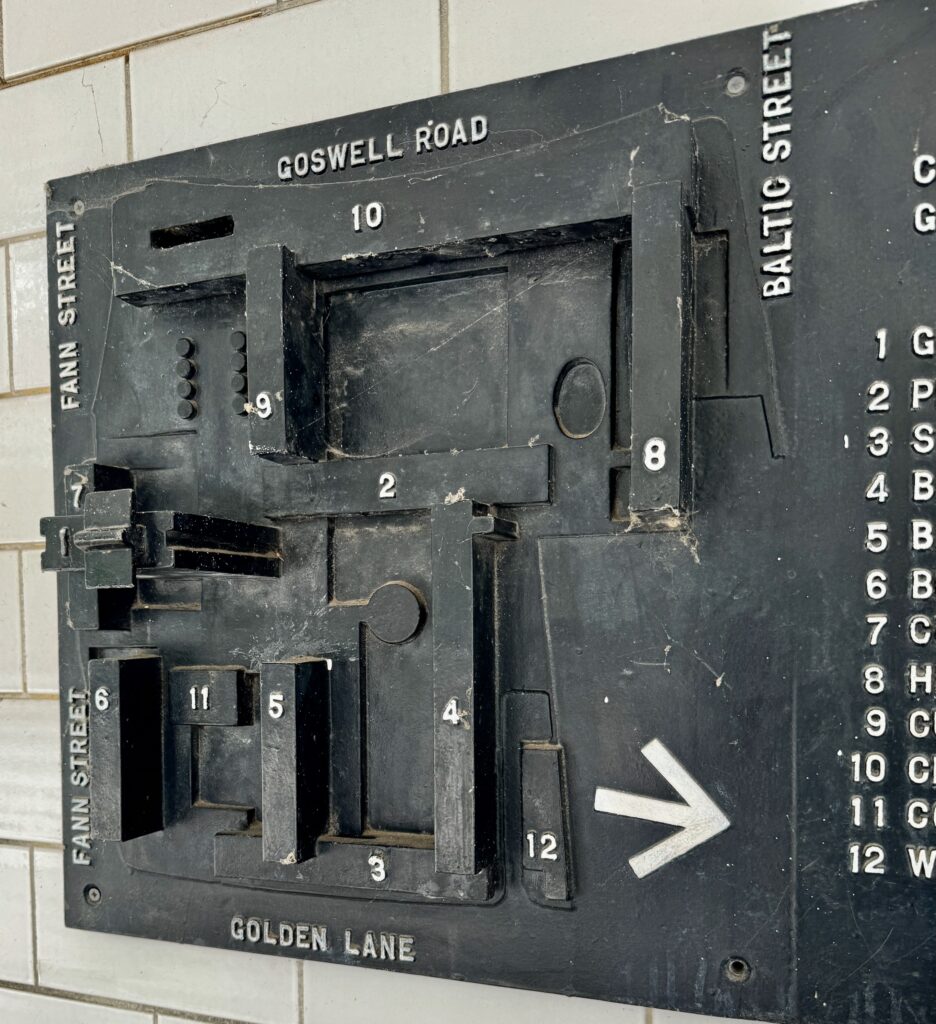

The Estate Map …

… with its wonderful the 3D representation …

I took these images on a sunny day last week …

In 1997 the whole estate was listed, including the landscaping and public areas at Grade II but Crescent House was separately listed Grade II* …

I glanced down Garrett Street where one can catch a glimpse of the old Whitbread stables …

You can read more about them here.

Further along on the left is what I call the ‘skinny house’ …

The MailOnline published a rather breathless article about it a few years ago. You can read it here.

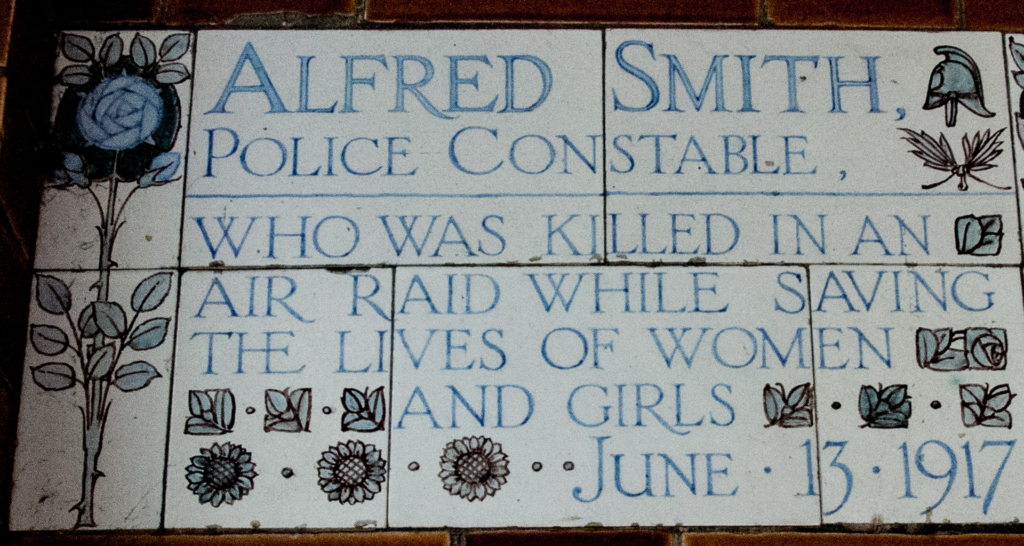

I crossed City Road and continued north on Central Street where this young man is commemorated by Islington Council (what a nice idea) …

Another First World War casualty …

PC Smith, 37 years old, was on duty nearby when the noise was heard of an approaching group of fourteen German bombers. One press report reads as follows …

In the case of PC Alfred Smith, a popular member of the Metropolitan Force, who leaves a widow and three children, the deceased was on point duty near a warehouse. When the bombs began to fall the girls from the warehouse ran down into the street. Smith got them back, and stood in the porch to prevent them returning. In doing his duty he thus sacrificed his own life.

Smith had no visible injuries but had been killed by the blast from the bombs dropped nearby. He was one of 162 people killed that day in one of the deadliest raids of the war.

His widow received automatically a police pension (£88 1s per annum, with an additional allowance of £6 12s per annum for her son) but also had her MP, Allen Baker, working on her behalf. He approached the directors of Debenhams (whose staff PC Smith had saved) and solicited from them a donation of £100 guineas (£105). A further fund, chaired by Baker, raised almost £472 and some of this was used to pay for the Watts Memorial tablet, below, which was officially unveiled in Postman’s Park on the second anniversary of Alfred’s death …

Next an Elizabethan postbox by the Carron Company of Stirlingshire …

Among other commissions, the company also produced the famous Giles Gilbert Scott telephone boxes. Despite diversifying into plastics and stainless steel, the company went into receivership in 1982.

On reaching the junction with City Road you’re faced with the extraordinary, innovative Bunhill 2 Energy Centre …

‘The new energy centre uses state-of-the-art technology on the site of a disused Underground station that commuters have not seen for almost 100 years. The remains of the station, once known as City Road, have been transformed to house a huge underground fan which extracts warm air from the Northern line tunnels below. The warm air is used to heat water that is then pumped to buildings in the neighbourhood through a new 1.5km network of underground pipes’.

An old trough and water fountain …

Read all about the history of drinking water supplies to the London working population and their animals in my blog Philanthropic Fountains.

Turn right into City Road and you encounter these remarkably lifelike characters and their dog …

This light display gives a clue as to what’s coming up …

The famous Eagle pub as mentioned in the rhyme …

At the beginning of the 19th century, ophthalmology was an unknown science but that all changed in the early 1800s as many soldiers returned from the Napoleonic wars suffering with trachoma. The original 1804 Dispensary for Curing Diseases of the Eye and Ear opened in Charterhouse Square in West in 1805. It moved in 1822 to a purpose-built building in Lower Moorfields and was renamed the London Ophthalmic Infirmary. When Queen Victoria gave it a royal charted in 1837 it became the Royal London Opthalmic Hospital but everyon still called it Moorfields. It still resides on City Road but has been vastly expanded …

The green line helps the visually impaired find their way from Old Street Underground Station …

The Alchemist bar goes green …

As does the roof of Old Street Station …

I’ll probably continue my stroll down City Road and beyond next week.

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …