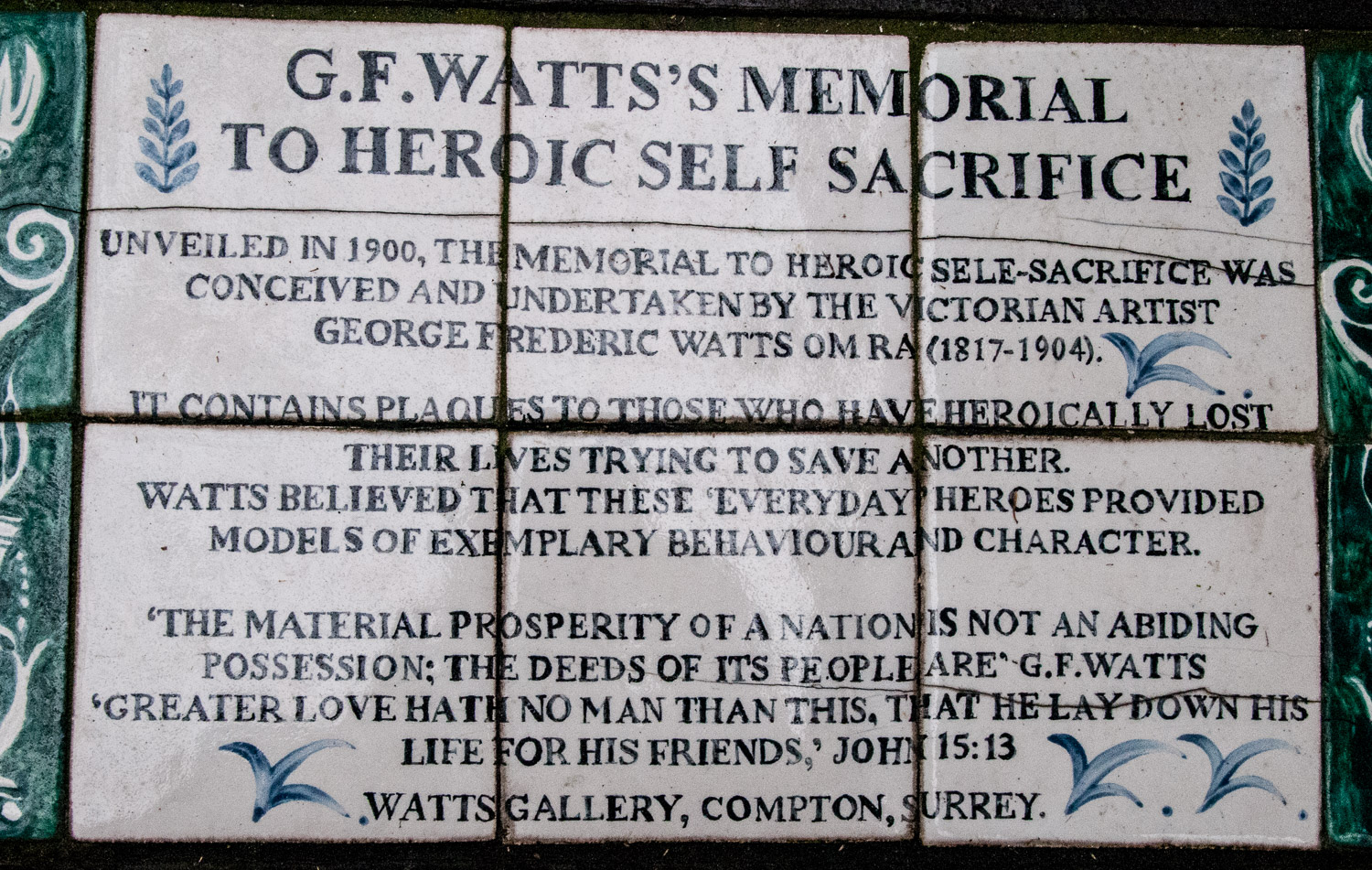

Postman’s Park contains what is, in my view, one of the most interesting, poignant and rather melancholy memorials in the City – The G F Watts Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice. This plaque nearby contains a useful mini-history …

I have written about it before along with some of the people commemorated and you can access the blog here.

I visited again last week and was moved to write about the bravery of four of the police officers whose names and details of their courageous acts are recorded on the Memorial.

George Stephen Funnell served for over seven years in the 2nd Battalion of the Oxford Light Infantry. He was discharged on 16th February 1893 and joined the Metropolitan Police the following October.

In this picture one of the medals he is wearing is probably the India General Service Medal with a Burma clasp …

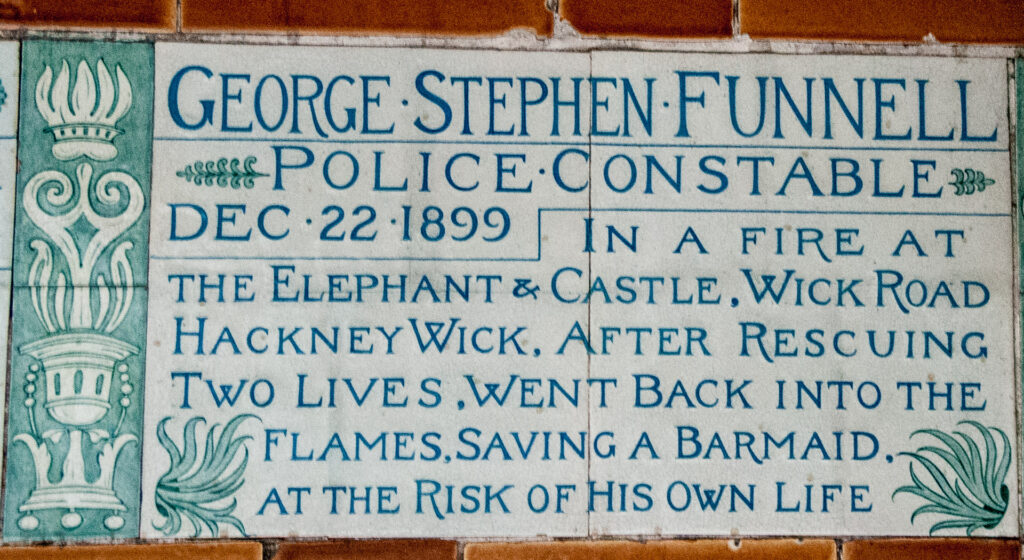

About 1:00 am on Friday 22nd December 1899 a fellow officer had noticed a fire at the Elephant & Castle pub in Wick Road and PC Funnell was one of the constables who came to his assistance. When the barman opened the door to let them in a massive draft of air escalated the fire dramatically. On hearing that there were three women in the building, Funnell and his colleague Thomas Baker rushed in to help rescue them amidst thick black smoke and exploding bottles of spirits.

Funnell led the first woman to the door and then went back to pick up and carry the second to safety. By then badly burned himself, on hearing another woman screaming, he went back in a third time and apparently collapsed when trying to find an alternative way out. The barmaid he was trying to help, Minnie Lewis, somehow managed to escape.

George was taken to the nearest infirmary but never regained consciousness and died on 2nd January 1900. He was 33 years old. This is his memorial plaque …

Five officers were awarded bronze medals by the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire but controversy arose over the treatment of Funnell’s 27-year-old widow Jane and his two young sons. The Globe was one of a number of newspapers who campaigned for the public to contribute to a fund for them, one journalist writing …

He leaves a widow, who receives a pension of £15 a year and £2 10s. for each of her two little boys until they reach fifteen. That is a miserable pittance indeed, and an appeal is made for public help.

I haven’t been able to discover how much was raised but it was probably substantial.

Extra funds were also raised for the widow of PC Alfred Smith …

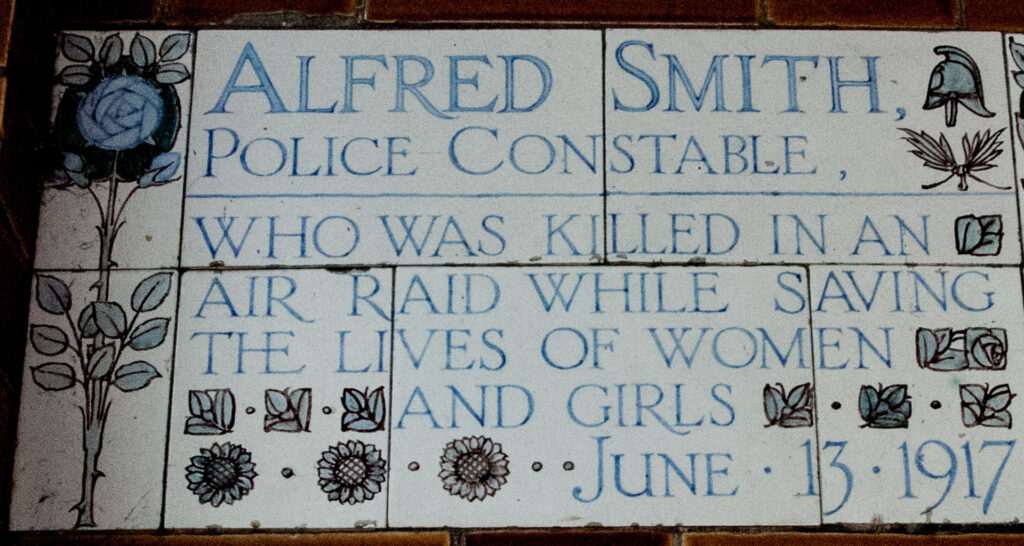

PC Smith, 37 years old, was on duty in Central Street when the noise was heard of an approaching group of fourteen German bombers. One press report reads as follows …

In the case of PC Alfred Smith, a popular member of the Metropolitan Force, who leaves a widow and three children, the deceased was on point duty near a warehouse. When the bombs began to fall the girls from the warehouse ran down into the street. Smith got them back, and stood in the porch to prevent them returning. In doing his duty he thus sacrificed his own life.

Smith had no visible injuries but had been killed by the blast from the bombs dropped nearby. He was one of 162 people killed that day in one of the deadliest raids of the war.

His widow was treated more generously than Mrs Funnell. She received automatically a police pension (£88 1s per annum, with an additional allowance of £6 12s per annum for her son) but also had her MP, Allen Baker, working on her behalf. He approached the directors of Debenhams (whose staff PC Smith had saved) and solicited from them a donation of £100 guineas (£105). A further fund, chaired by Baker, raised almost £472 and some of this was used to pay for the Watts Memorial tablet, which was officially unveiled on the second anniversary of Alfred’s death.

Another memorial to Alfred was unveiled 100 years later in June 2017 where the factory once stood …

Tragically another police constable, Robert Wright, died in vain …

He responded to a colleague’s whistle and arrived at the scene where a shop, known to contain large quantities of flammable and explosive material, was quickly being consumed by flames.

He and another PC, Edward Barnett, were clearing dangerous material from the yard at the back of the shop when Barnett thought he heard screaming and shouted to Wright ‘Quick, there is a woman in the house!‘ They managed to get upstairs through heavy smoke and with burning oil dripping through the ceiling – and found no one, the residents having gone on holiday. Barnett managed to jump to safety through a window but Wright was overcome by the smoke and was later declared dead on arrival at hospital. Although he was badly scalded the cause of death was given as smoke inhalation …

Police Constable Robert Wright (1864 – 1893) from Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper 7th May 1893. Copyright, The British Library Board.

Serious accusations of fire brigade incompetence and drunkenness were made at the inquest. The brigade was stationed only 300 yards down the road and it was claimed that a message was sent to them at 1:10 am but that they didn’t arrive until 1:45 am. It was also claimed that at least two brigade members were so drunk they could not carry out their duties. The senior fire officer, Engineer Bowers, conceded that this was true but, by way of some kind of explanation, said that one of them was a retained man and the other from the volunteer brigade. The coroner suggested that the men should ‘…receive the attention of the Corporation’.

Incidentally, Wright’s widow’s pension was £15 a year plus an extra £2 10s for her daughter Ada until she was 15.

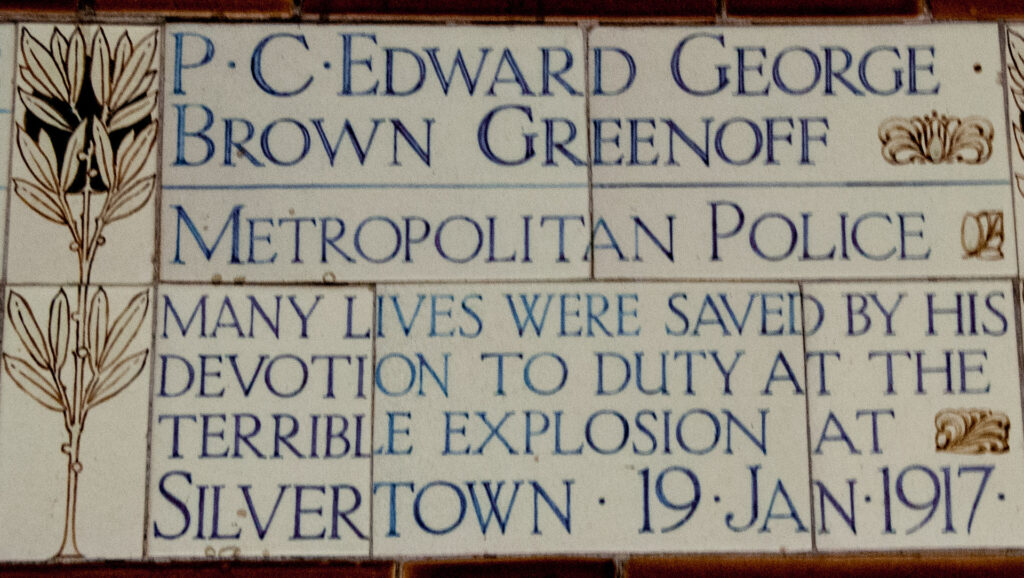

For some reason I had never heard of the Silvertown explosion that claimed the life of PC Edward George Brown Greenoff …

Edward joined ‘K’ Division of the Metropolitan Police on 7 December 1908 Less than three weeks after joining the police, he married Ada Mina Thorpe, and they went on to have three children, Edward Arthur Cecil (born 1909), Elsie Irene (born 1912) and Albert George (born 1914).

On his beat was a factory manufacturing TNT – although that had not been its original purpose and it was in the middle of a built up area. As he passed the site around 6:00 pm on 19th January 1917 he noticed flames billowing from the premises and a fire engine in attendance. Being fully aware of the danger, Greenoff ran towards the building to help in the evacuation and at the same time persuade the crowds who had gathered to watch to move back.

At 6.52 pm precisely there was a massive explosion as approximately 50 tons of TNT ignited. The blast destroyed a large part of the factory, buildings on the southern side of the Royal Victoria Dock and many houses in the surrounding streets. Debris, amongst it red-hot chunks of rubble, was strewn for miles around. These images give some idea of the destruction …

The death toll was 73 with more than 400 people injured.

Edward was found seriously hurt in the rubble and died on 29th January aged 30. On 26 June 1917, he was awarded the King’s Police Medal for Gallantry. The citation reads …

Died from injuries received on 19 January from an explosion at a fire in a munitions factory at Silvertown where, despite the imminent danger, he remained at the scene to warn others and evacuate the area.

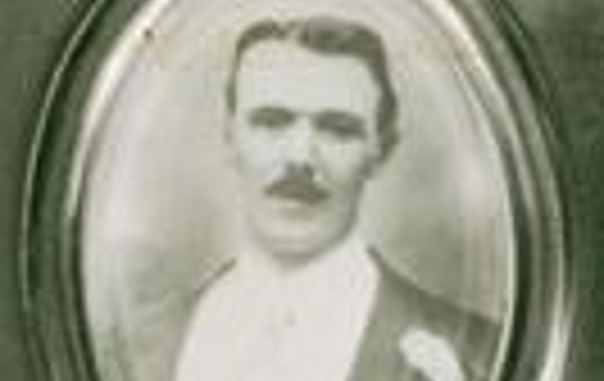

He was also commemorated in an ornate memorial plaque originally erected in North Woolwich Police Station. It contains this photograph, which was probably taken on his wedding day given the flower in his buttonhole …

If you are interested, you can read much more about the Silvertown explosion here.

There is a nice small statuette in the middle of the Memorial of Mr Watts himself that was installed in 1905, the year after he died. There was originally a plan to cover it with a protective grille but his widow refused and said the public should be trusted …

He holds a scroll on which is inscriber the word HEROES.

For the definitive life histories of the Watts Memorial heroes treat yourself to a copy of John Price’s book Heroes of Postman’s Park – Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London.

There is also a very useful guide on the London Walking Tours website.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …