Yesterday I came face to face with the harsh reality of life in the 18th century.

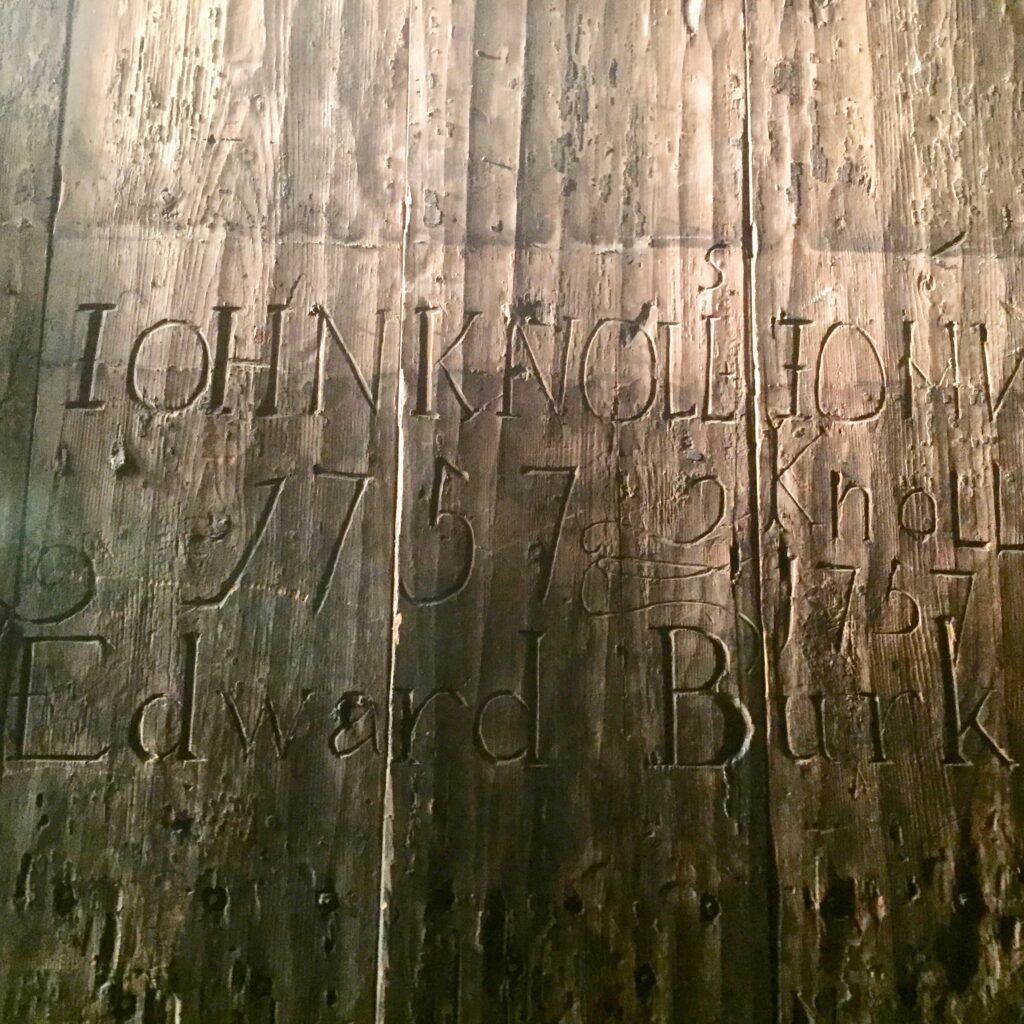

In the Museum of London I went and stood in a room constructed using cell walls from the old Wellclose Square debtors’ prison and looked in awe at the names and images inscribed by unfortunate inmates. Although we can read some names we will never know more about them which makes this an even more melancholy place.

For example, John Knolls and Edward Burk were there in 1757 …

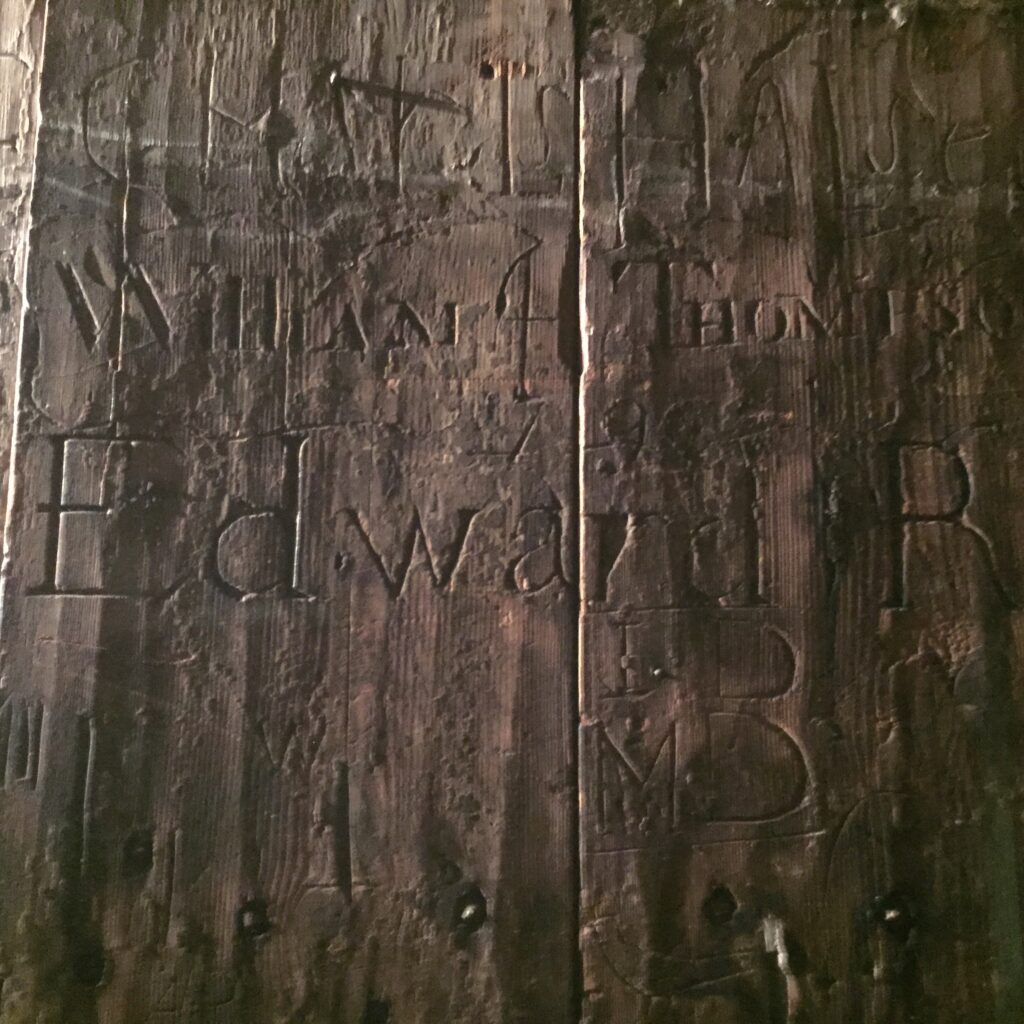

And William Thompson in 1790 or 1798. Just above his name someone has scratched what looks like a gallows (sometimes people were held here on their way to be punished more severely at places like Newgate) …

Some just left their initials …

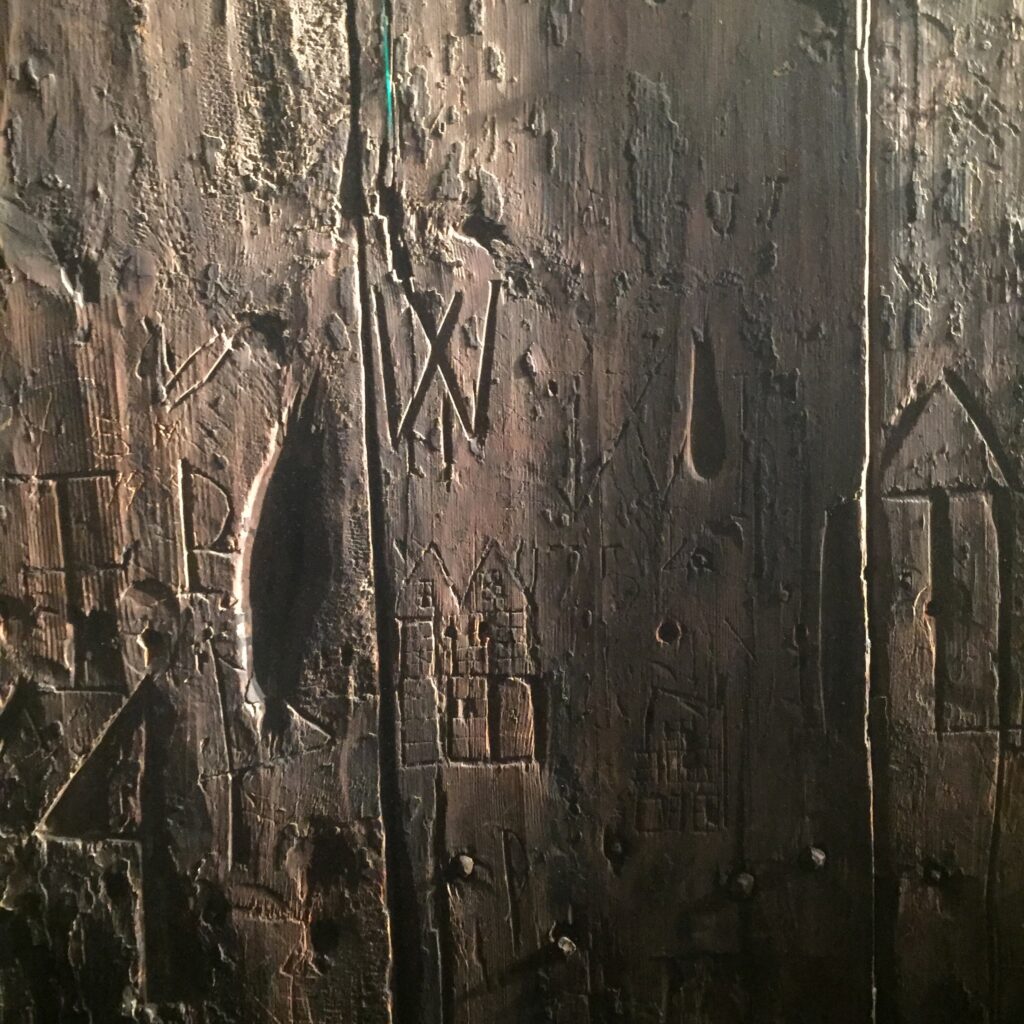

Others chose to carve elaborate representations of buildings …

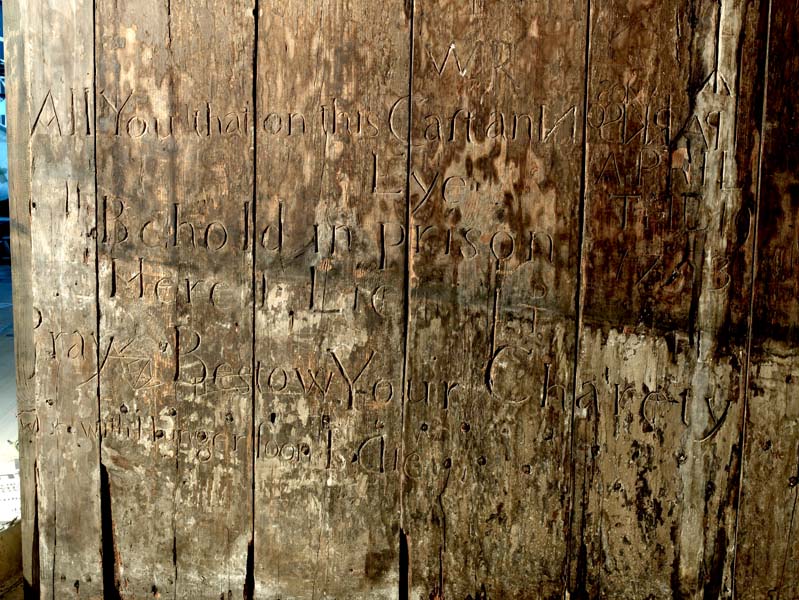

And this person sent out a poetic plea …

All You That on This Cast an Eye, Behold in Prison Here I Lie, Bestow You in Charety, Or with hunger soon I die.

The lighting is set low to represent candlelight …

This is how it looked just after assembly …

The Gentle Author, in his empathic and beautifully written blog about this room, writes …

Shut away from life in an underground cell, they carved these intense bare images to evoke the whole world. Now they have gone, and everyone they loved has gone, and their entire world has gone generations ago, and we shall never know who they were, yet because of their graffiti we know that they were human and they lived.

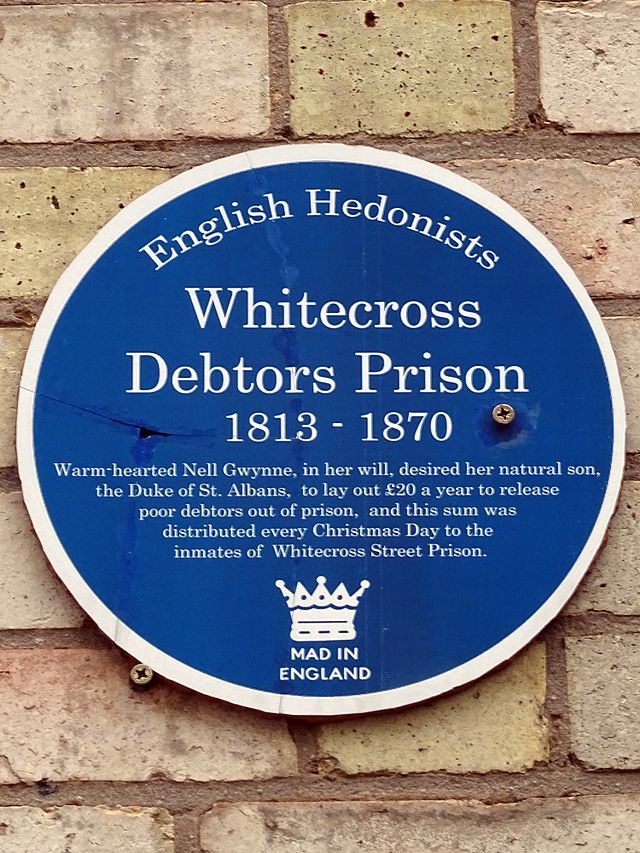

When walking along Whitecross Street one day I was intrigued by this spoof blue plaque on the wall of the Peabody Buildings …

British History Online confirms the Nell Gwynne story but I cannot find another source. It also tells us that …

A man may exist in the prison who has been accustomed to good living, though he cannot live well. All kinds of luxuries are prohibited, as are also spirituous drinks. Each man may have a pint of wine a day, but not more; and dice, cards, and all other instruments for gaming, are strictly vetoed.”

A pint of wine a day doesn’t sound too bad.

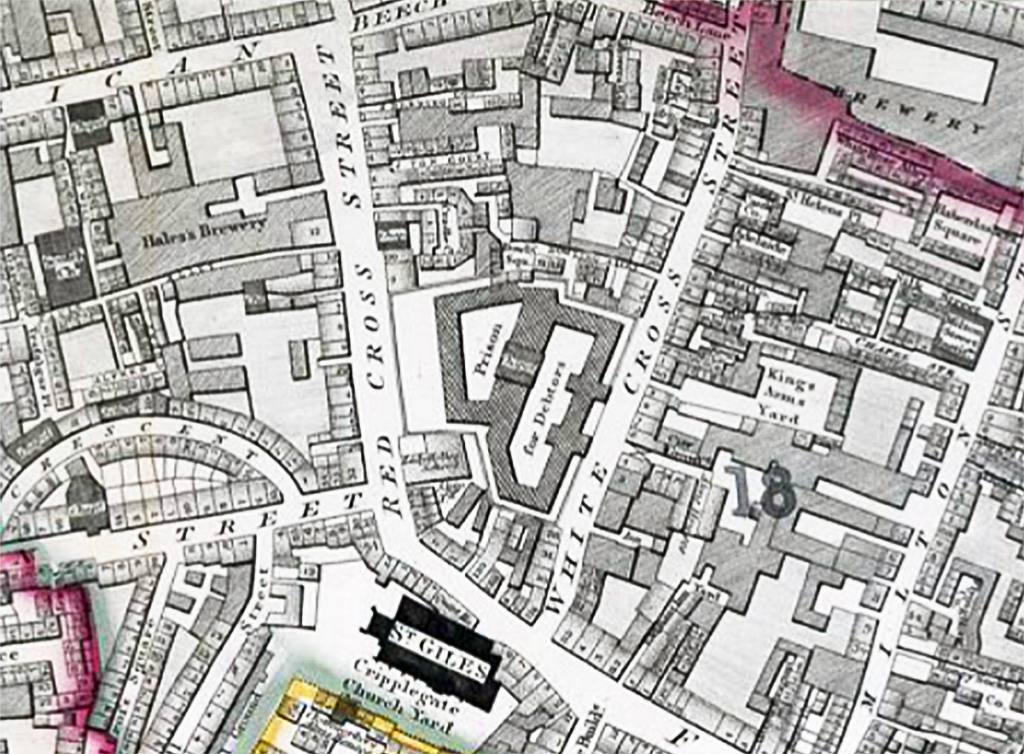

The prison was capable of holding up to 500 prisoners and Wyld’s map of London produced during the 1790s shows how extensive the premises were …

Prisoners would often take their families with them, which meant that entire communities sprang up inside the debtors’ jails, which were run as private enterprises. The community created its own economy, with jailers charging for room, food, drink and furniture, or selling concessions to others, and attorneys charging fees in fruitless efforts to get the debtors out. Prisoners’ families, including children, often had to find employment simply to cover the cost of the imprisonment. Here is a view of the inside of the Whitecross Street prison with probably more well off people meeting and promenading quite normally …

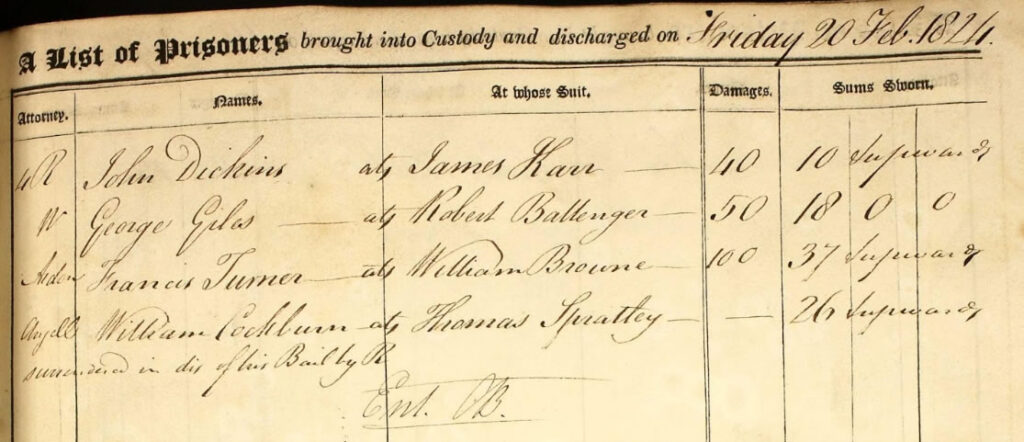

Creditors were able to imprison debtors without trial until they paid what they owed or died and in the 18th century debtors comprised over half the prison population. Prisoners were by no means all poor but often middle class people in small amounts of debt. One of the largest groups was made up of shopkeepers (about 20% of prisoners) though male and female prisoners came from across society with gentlemen, cheesemongers, lawyers, wigmakers and professors rubbing shoulders. For example, Charles Dickens’ father, John, spent a few months at the Marshalsea in 1824 because he owed a local baker £40 and 10 shillings (over £3,000 in today’s money). Here is his custody record dated 20th February 1824 …

Charles – then aged just 12 – had to work at a shoe-polish factory to help support his father and other members of his family who had joined John in prison. It was a humiliating episode from which the author later drew inspiration for his novel Little Dorrit. Many years later Dickens described his dad as ‘a jovial opportunist with no money sense’!

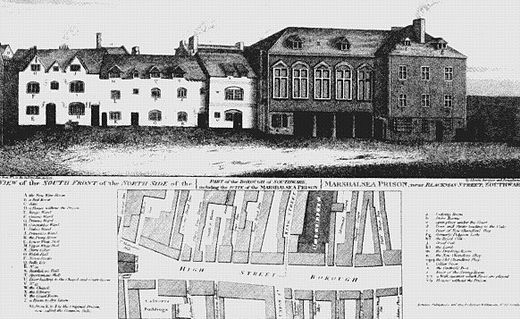

This was the notorious Marshalsea …

It was located in Southwark, the historic location of theatres, bear-pits and whorehouses and in the mid-17th century it settled into being exclusively a debtors’ jail. Then it was full to bursting and people could be thrown in for owing as little as sixpence. In such a case, he or she was charged in “Execution”, which immediately increased the indebtedness to £1 5s 6d, making it much less likely that the prisoner could ever get out. ‘More unhappy people are to be found suffering under extreme misery, by the severity of their creditors,’ one commentator noted, ‘than in any other Nation in Europe’. Without money, you were crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten prisoners were dying every twenty-four hours in the warmer weather.

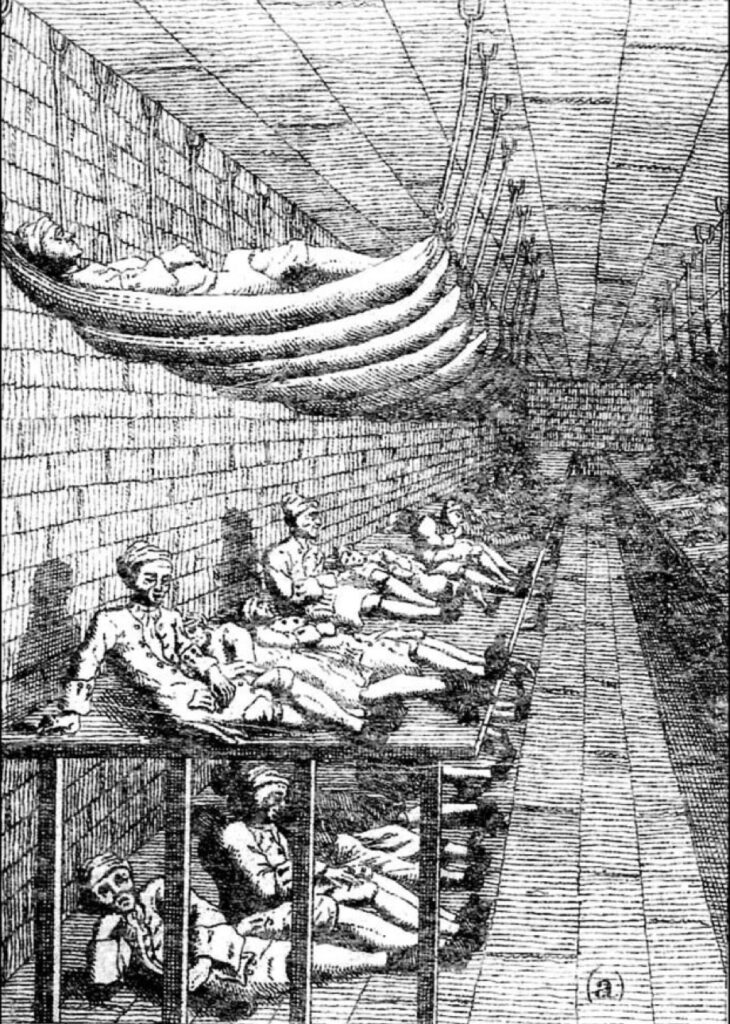

Not surprising when you look at this 18th-century engraving of the Marshalsea sick ward and the poor souls incarcerated there …

Part of the old prison wall is still there …

And appropriately an old grille from the prison is preserved in the Charles Dickens Museum …

Imprisonment for debt was finally abolished in 1869, ending centuries of misery. I found this quite an addictive subject and if you are as interested as me in knowing more here are the major sources I used :

An absolutely fascinating description of one man’s first 24 hours in Whitecross Street prison. Particularly interesting is the description of some of his fellow inmates and what the charges were for ‘extras’ like sheets on your bed or a piece of paper to write on. Ignore the fact that it is mistakenly illustrated with a picture of a hanging at Newgate Gaol.

In British History Online there is a description of the Whitecross Street establishment at the end of Chapter XXIX.

An article entitled DEBTORS’ PRISONS WORKED: Evidence from 18th century London.

An article entitled : In debt and incarcerated: the tyranny of debtors’ prisons.

The distinguished London historian Jerry White’s book specifically about the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison : Mansions of Misery.

A presentation : The Real Little Dorrit: Charles Dickens and the debtors’ prison.

Finally, if you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …