On Sunday 30th September 1888 at about 1.45 in the morning Police Constable 881 Edward Watkins turned into Mitre Square, a regular part of his beat.

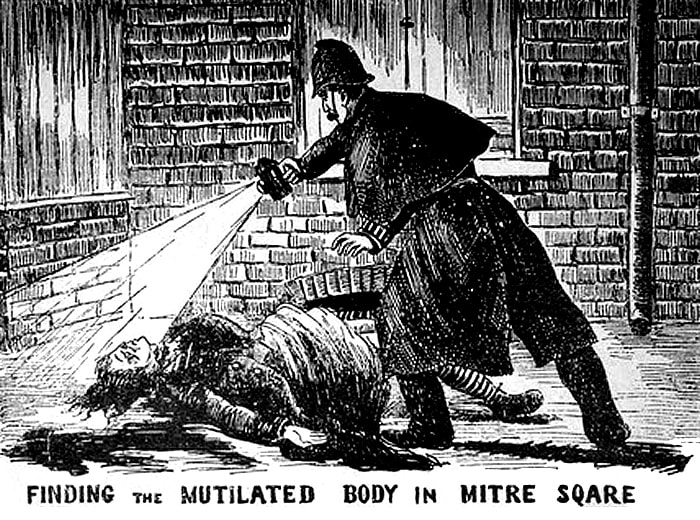

In the southernmost corner, clearly picked out by the bullseye lantern on Watkins’s belt, lay the terribly mutilated body of a woman. Watkins ran across to Kearley and Tongue’s warehouse, knowing that the watchman there, George James Morris, was a retired police officer. Watkins found the door to the warehouse ajar, pushed it open, and found Morris sweeping the steps that led down toward the door.

‘For God’s sake, mate, come to my assistance,’ cried Watkins.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Morris, to which Watkins replied, ‘There’s another woman cut to pieces.’

The woman was Catherine Eddowes* and she was destined to be named as the fourth victim of the Whitechapel Murderer, more commonly known as Jack the Ripper.

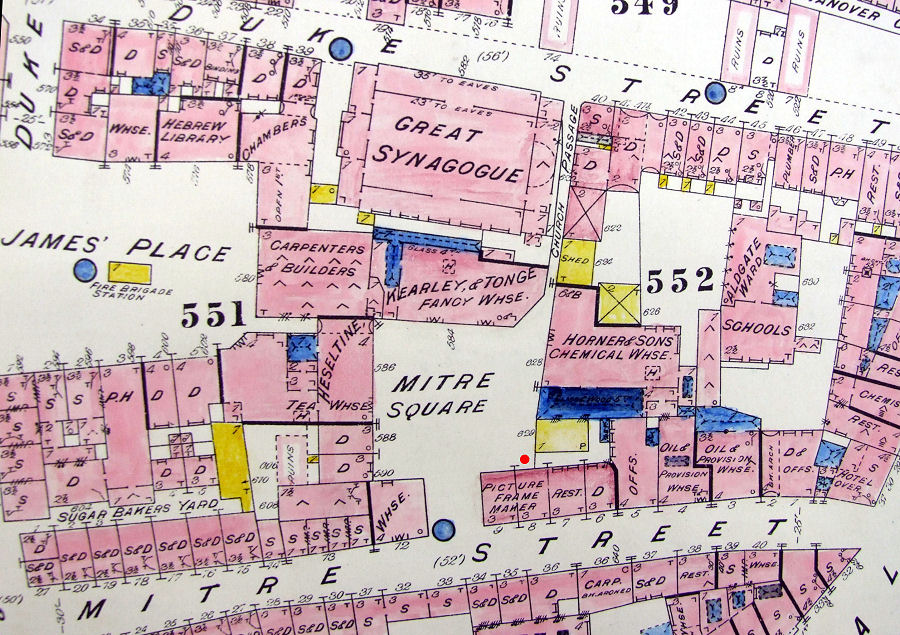

Around this time Charles Goad was compiling maps for use by the fire insurance companies and this is one of his earliest prepared just 20 months before the murder. The red spot indicates where the body was found …

The murder scene …

The Square today – I think I am standing approximately where she was was discovered …

The fact that ‘Jack’s’ identity has never been agreed upon has led to the practice commonly called Ripperology in which the crimes and possible perpetrators are endlessly debated and discussed. Needless to say there are numerous sources online but I found this one to be one of the most interesting including as it does a poignant list of poor Catherine’s possessions. You can find an account of her funeral here. (By the way, you can see an authentic police bullseye lantern in the City of London Police Museum and a picture in my blog The City’s Little Museums).

In the centre of my photograph of the Square today is an example of the Sculpture in the City initiative …

This is Climb by Juliana Cerqueira Leite. In this fascinating YouTube clip she explains how it was created.

As you stand in Mitre Square you can often hear children playing. They are pupils at Sir John Cass’s Foundation Primary School …

Sir John Cass was born in the City of London in 1661 and during his lifetime served as Alderman, Sheriff and the City’s MP.

In 1710 he set up a school for 50 boys and 40 girls and rented buildings in the churchyard of St Botolph Without Aldgate. Cass intended to leave the vast majority of his property to the independent school but, when he died in 1718, had only initialled two of the eight pages of his will. The incomplete will was contested, but was finally upheld by the Court of Chancery thirty years after his death. The school, which by this time had been forced to close, was re-opened, and the foundation established.

There is an old legend that he had a haemorrhage of the lungs which stained the quill pen with which he was initialising his will, and it is for this reason that the pupils of the school still wear red goose quills when they attend St Botolph’s Church on the anniversary of their Founder’s birth each year.

Two statues of children in blue coats stand over the previous girls’ and boys’ entrances …

Blue was the distinctive colour for paupers, charity schools and almsmen, (hence Bluecoat Boys and Girls) and Cass’s School would have been called a Bluecoat School. By extension it typified the dress of tradesmen so that ‘To put on a blue apron’ meant to take up a trade. Incidentally, the great diarist Samuel Pepys, recording a trade riot in London in 1664, tells us that ‘At first, the butchers knocked down all the weavers that had green or blue aprons.’ Those were the days.

Here’s a bust of Sir John as displayed in the nearby church of St Botolph Without Aldgate, which I shall write about in a later blog …

On the school gates I noticed this very appropriate instruction …

I took this picture of St Botolph’s whilst standing behind another Sculpture in the City exhibit by Jyll Bradley …

Made from coloured sheets of edge-lit Plexiglas turned on their side and leant against a south-facing wall, Dutch / Light (for Agneta Block) creates an open-glasshouse pavilion that is activated by the sun. The work references the so-called ‘Dutch Light’ a horticultural revolution that hit British shores over three centuries ago as Dutch growers pioneered early glasshouse technology.

There is lots more to see around Aldgate and St Botolph’s so I shall return next week.

Do remember that you can follow me on Instagram :

https://www.instagram.com/london_city_gent/

*None of the research I have done suggests that Catherine was a prostitute and this is confirmed in a new book, The Five, by Hallie Rubenhold, which you can read more about here.